The Boston Sound

Depending on what you were listening to in 1968, your recollection of “the Boston sound” is one of three things: (a) just another example of the usual record company hype, with little to show for it; (b) a good opportunity for some creative and talented Boston-area bands to get some much-deserved national attention; or (c) a little bit of both.

Promoted as “the Bosstown Sound” (a play on “Motown”), the short-lived initiative inspired extremely polarizing opinions, among fans, journalists and critics alike. To this day, some dismiss it entirely but others believe several of the bands are well worth remembering.

Background

By most accounts, the Bosstown Sound was intended to be a reaction to the San Francisco Sound at a time when West Coast-based bands like Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service and Moby Grape were becoming more popular by the week. In the 1950s and well into the 1960s, top-40 AM radio was king and FM was home to mainly classical music but tastes were gradually changing; by the mid-60s, a few FM stations were playing a new kind of music that drew throngs of college-aged listeners – “underground” aka “psychedelic” rock.

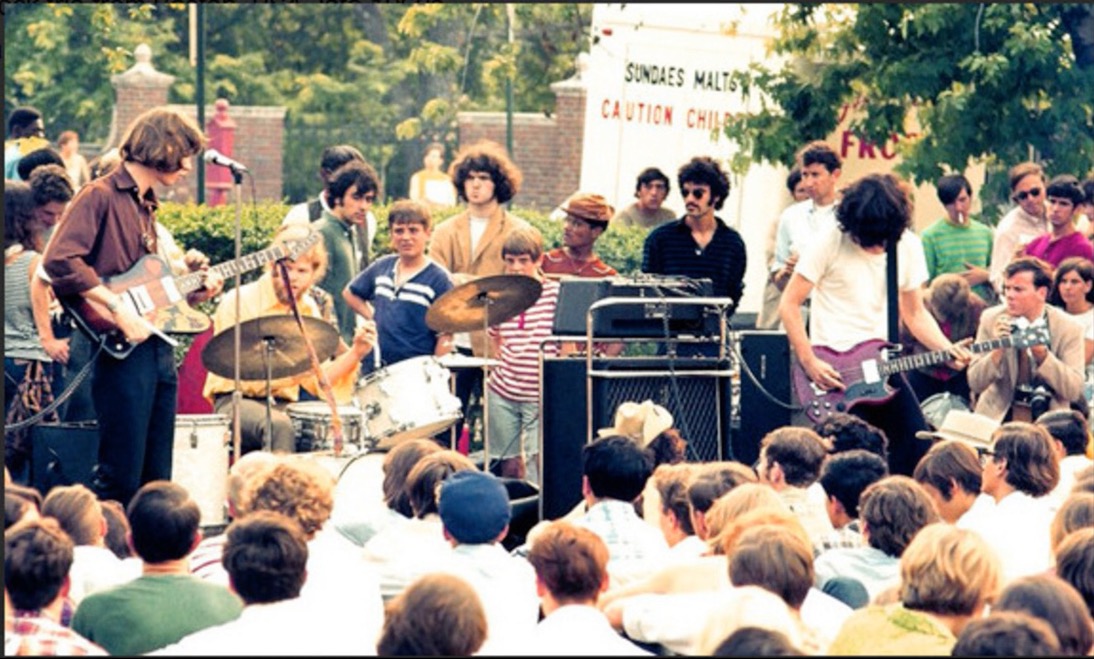

In 1967, as now, Boston was a college town. By some estimates, the greater Boston area had as many as 200,000 students that year. While there was a vibrant folk-music scene already, by 1967 there was also a growing number of underground and progressive rock bands and one of the few places you could hear them (other than at a few local clubs) was on WTBS (now WMBR), a low-watt college station out of MIT in Cambridge.

WTBS deejay “Uncle T” (Tom Gamache) was one of the first to broadcast underground/psychedelic rock and progressive rock. By 1967, he had moved his show to Boston University’s WBUR, which had a 20,000-watt signal that made his show more widely available than his one on WTBS. (Note: There wasn’t a commercial FM rock station in Boston until WBCN changed its format from classical to rock in mid-March 1968.) By early 1967, there was also a new venue where underground and psychedelic rock bands could perform, The Boston Tea Party, which showcased groups that received little or no airplay on the AM airwaves.

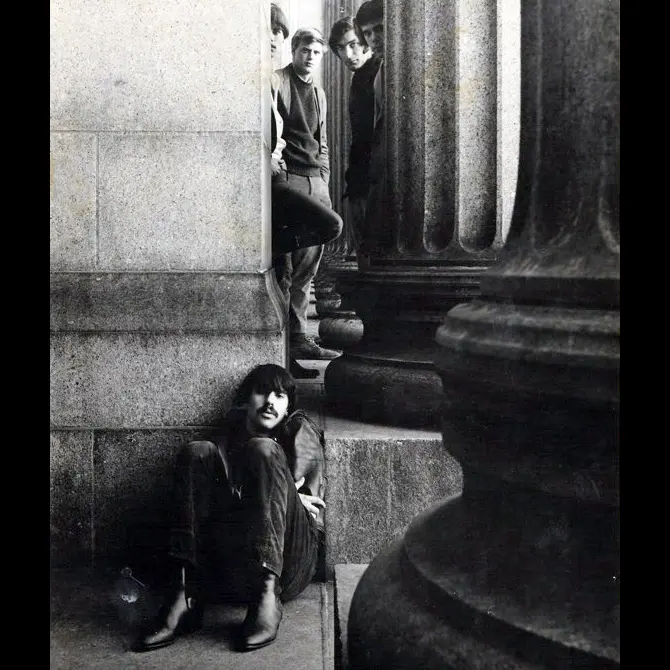

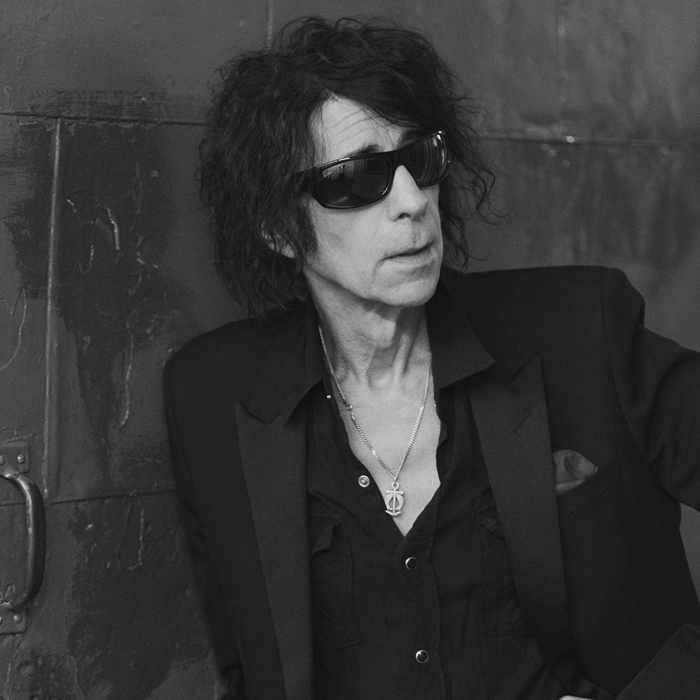

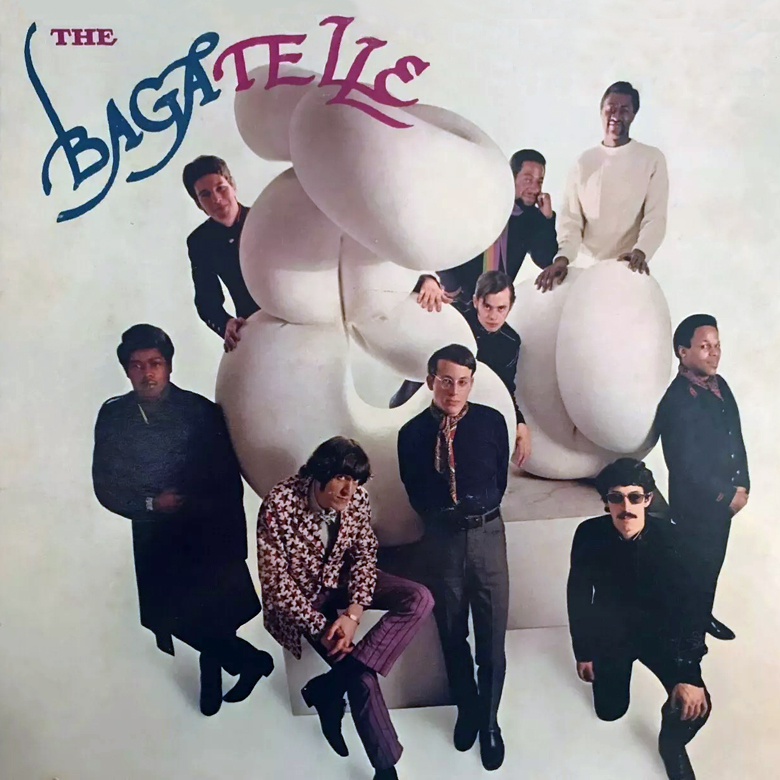

With or without top-40 AM-radio support, Boston now had popular local bands with psychedelic sound Phluph, Ill Wind and Eden’s Children, who had developed small-but-strong local followings. One band that Uncle T especially liked was The Hallucinations, fronted vocalist Peter Wolf (later of The J. Geils Band). But the Boston music scene wasn’t easy to categorize, since not all of the most popular bands fit into the psychedelic genre. For example, The Bagatelle was an eight-piece group whose material mixed rock and R&B.

By 1967, it had become obvious to record companies that top-40 was no longer reaching college-aged record buyers. As a result, talent scouts began visiting cities that had active music scenes, seeking bands that appealed to college-age fans (who bought lots of records, and were becoming caught up in the psychedelic music craze). And that brought national attention to Boston.

Alan Lorber, “Bosstown Sound” bands

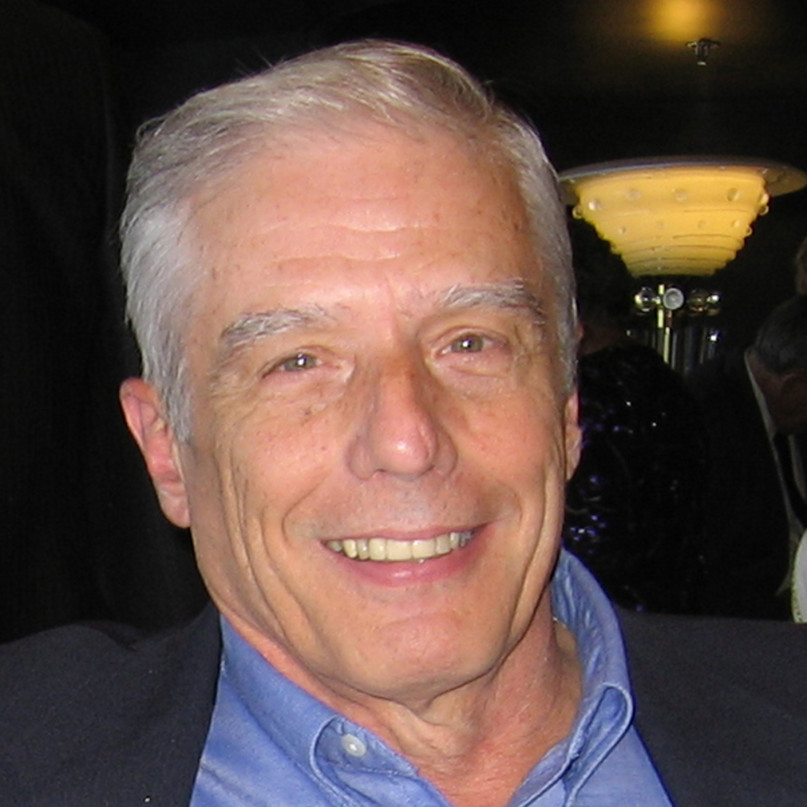

One New York City-based record producer who came to explore the city’s thriving scene was Alan Lorber. But he was not only a producer; he was also an arranger and a composer and – most importantly for bands wanting to get signed to a major label – had close ties to MGM Records through his production company. In the summer of 1967, he entered into an agreement with David Jenks and Ray Paret, who ran Boston-based management outfit Amphion, and began checking out some of the clubs in Boston and the surrounding area.

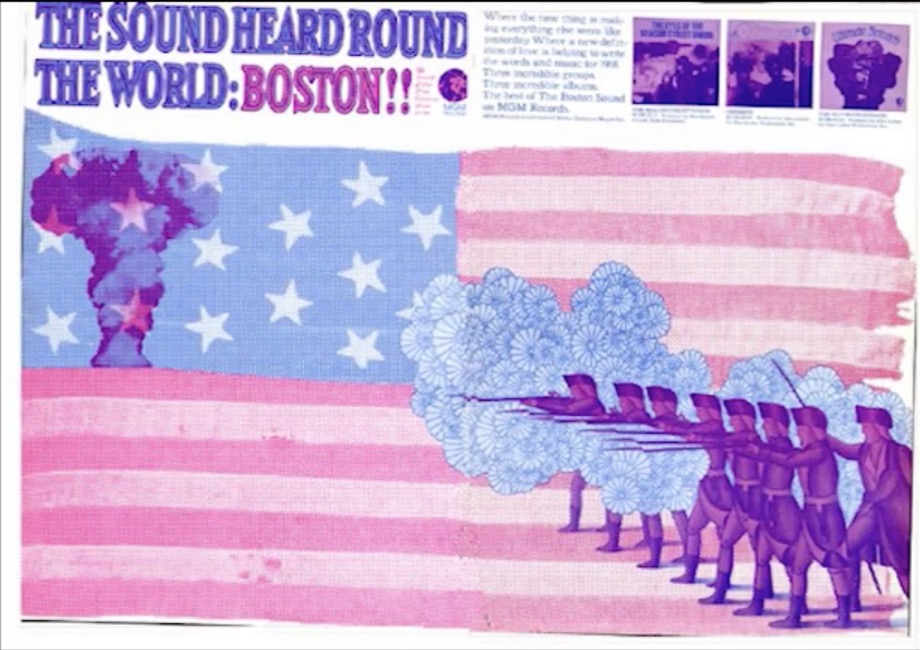

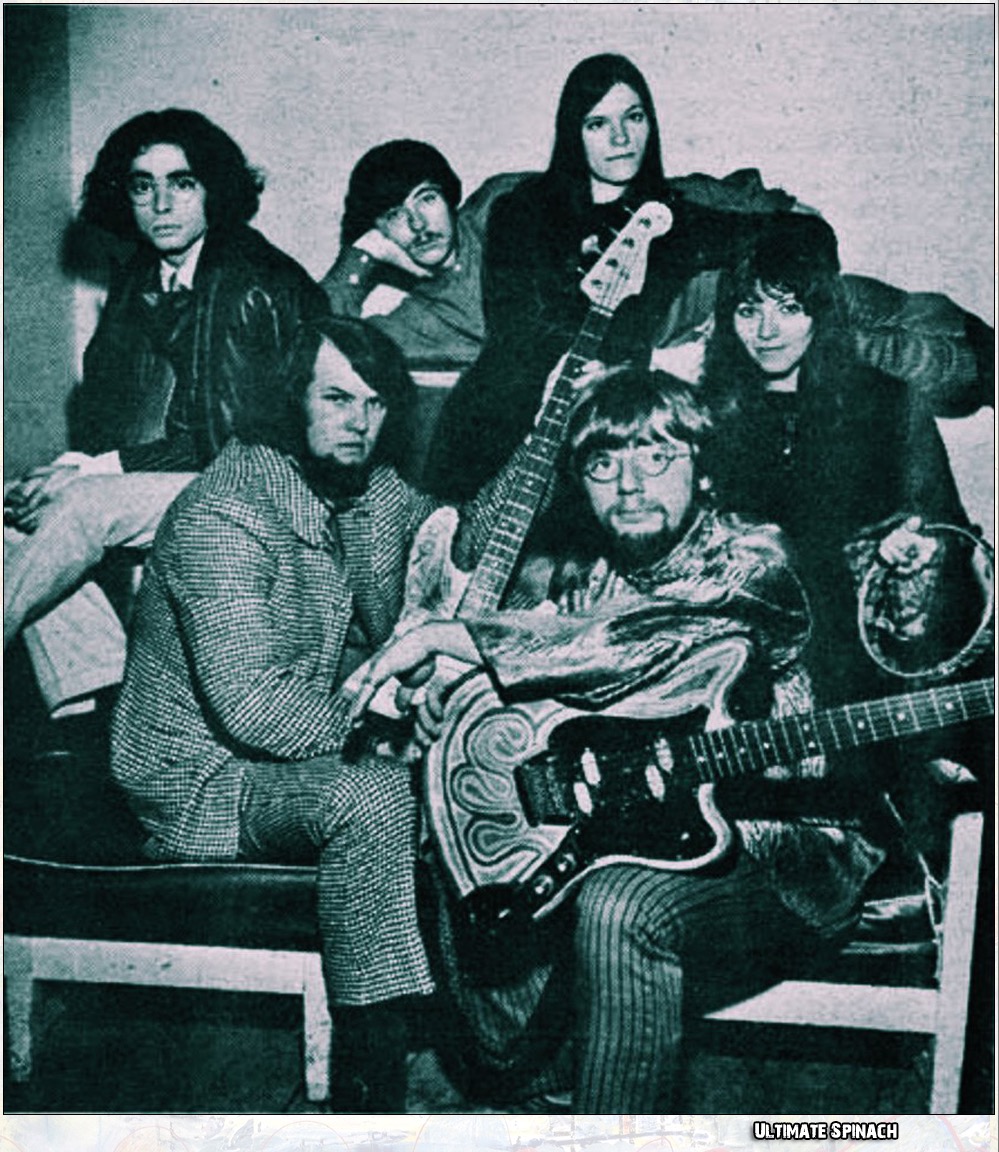

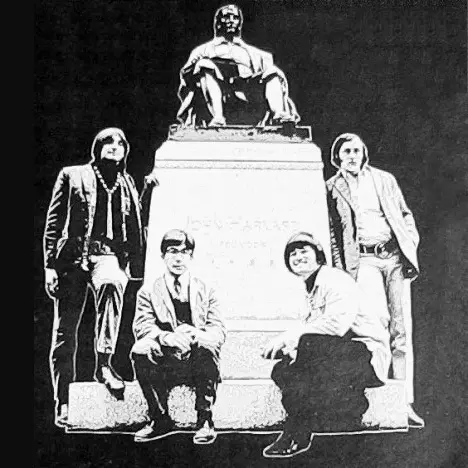

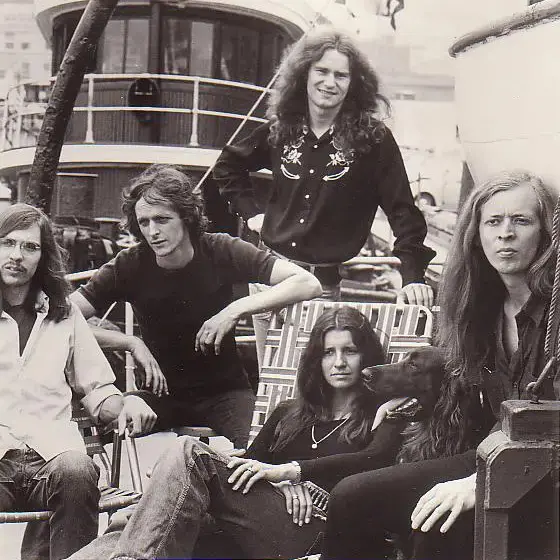

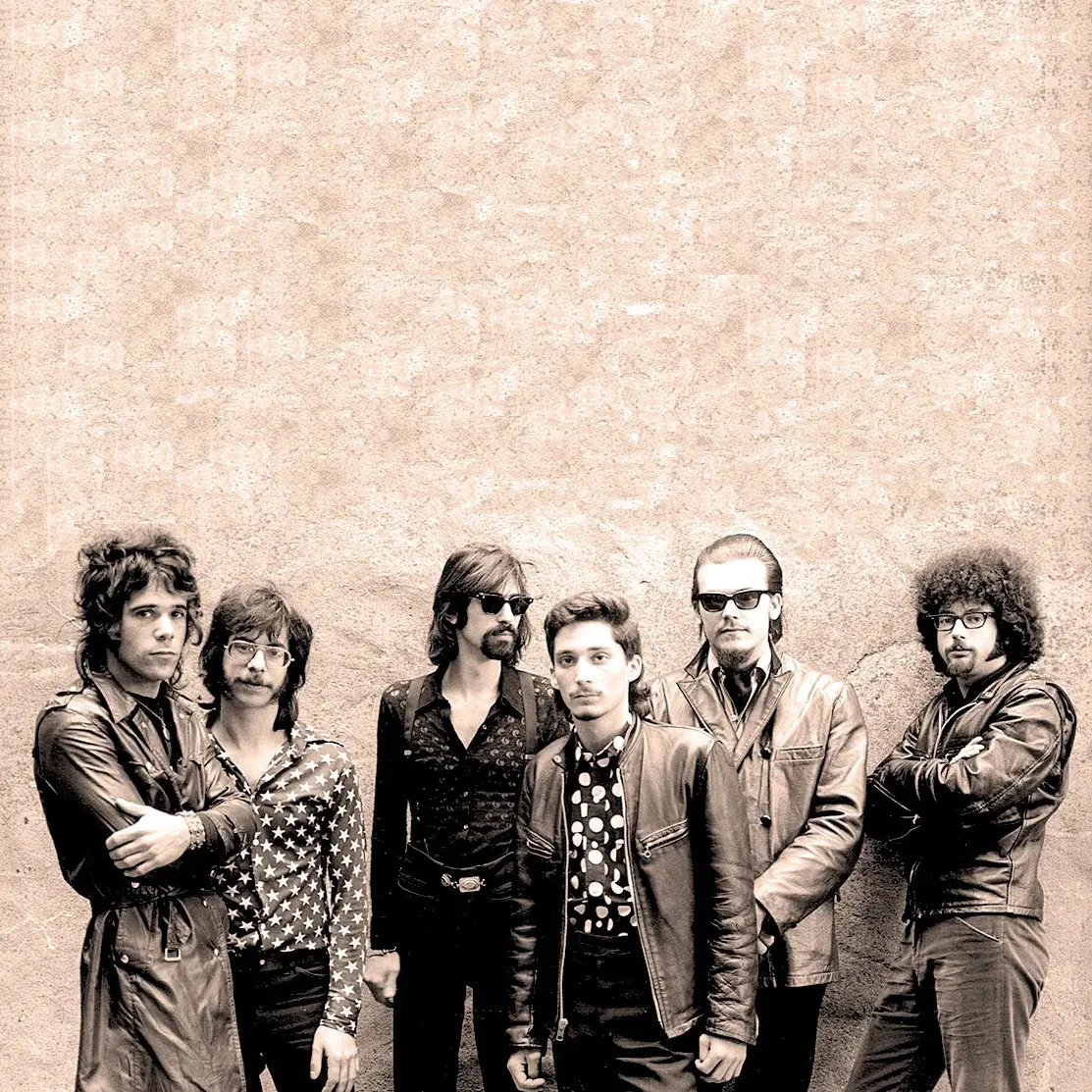

Among the first bands he saw were Ultimate Spinach and Orpheus and he wound up producing both groups when they joined the MGM roster. The Beacon Street Union, another local band with a sizable fan base, went to New York City to play some clubs dates and they caught the eye of producer Wes Farrell, who wanted to record them. They also ended up on MGM and the label packaged them, Orpheus and Ultimate Spinach together in a full-page ad that ran in Billboard, Cash Box and Record World on January 20, 1968. The catch copy was “the sound heard ’round the world: Boston!!” Some sources have said the concept of “the Bosstown Sound” came from Alan Lorber himself; others claim it came from MGM Records’ marketing and promotion department. In any event, there’s no denying that Lorber was the first major music industry figure to recognize Boston’s unique hit-making potential

Dick Summer, Larry Justice

Every trend in music, real or imaginary, needs a champion and in Boston, an AM deejay named Dick Summer decided to give the Bosstown sound bands plenty of airplay and lots of positive commentary. Summer was a well-loved personality who did overnight shift on WBZ, a powerhouse AM station with 50,000 watts; the time slot allowed him more freedom than his colleagues when it came to playing untested material and many of his listeners were college students.

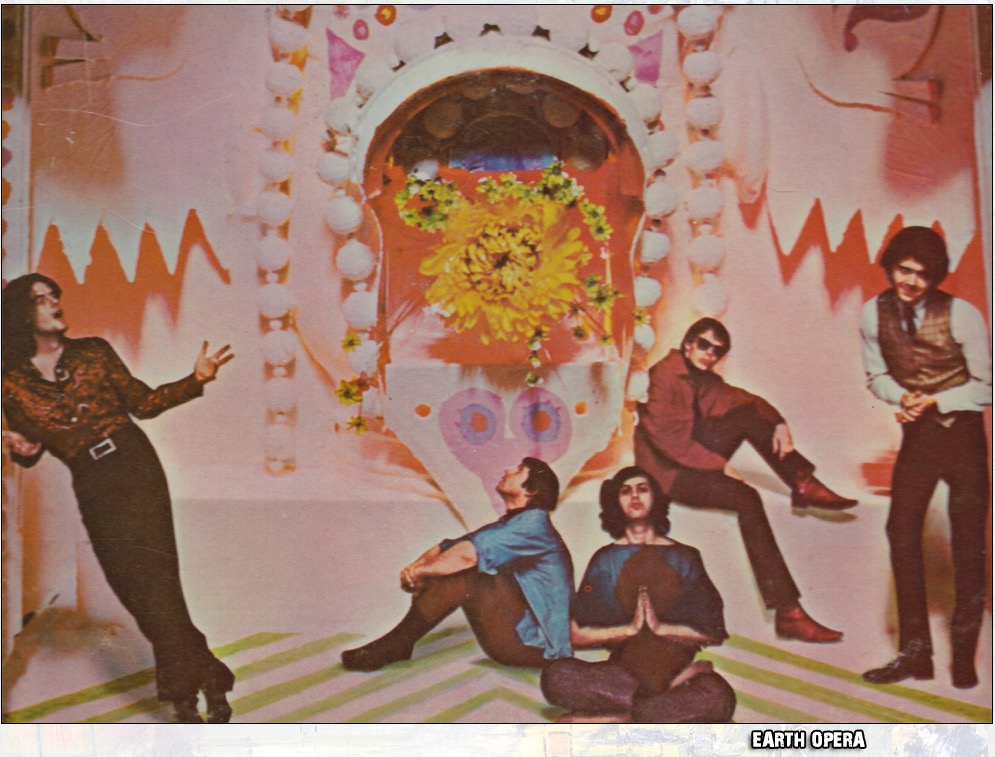

Summer began spinning the first Bosstown Sound albums as soon as they were released in early 1968. He was not the only Boston deejay to do so, however; over at his competition, AM station WMEX, Larry Justice also gave the Lorber-produced groups some attention. By mid-1968, several other local acts had landed record deals with major labels: Eden’s Children, Ill Wind and The Bagatelle signed with ABC Records after the label’s A&R director Bob Thiele saw them in Boston and Earth Opera signed with Elektra.

Critical response

The diversity of musical styles among Bosstown Sound groups proved to be a problem for critics who wanted an easy way to describe it. Interestingly, some of the artists themselves wondered whether trying to unite them all under the banner of the Bosstown Sound was a wise decision. In a March 1968 interview with Record World, several members of The Beacon Street Union said they disliked “being lumped in with a lot of other people as part of the Boston Sound…We want to be ourselves.”

So, what exactly was the Bosstown Sound? Some bands were easy to classify since they fit into the psychedelic genre perfectly, like Ultimate Spinach. But others, such as Orpheus, featured melodic pop that saw significant airplay on numerous top-40 stations. In fact, their song “Can’t Find the Time” was boosted by influential columnist Kal Rudman, who wrote the “Money Music” column for Record World magazine and was convinced the Bosstown Sound was for real. He predicted that Orpheus would have a hit and he was right; in early 1968, “Can’t Find the Time” reached #80 in the Billboard Hot 100.

That success aside, however, critics who were unsure what the Bosstown Sound actually meant weren’t shy about expressing their skepticism; they saw it as more hype than anything else. In March 1968, Robert Shelton of The New York Times wrote that this alleged new trend was “mostly [record company] puff” while acknowledging that some of the bands were talented and might find some success. Other critics were harsher, especially Jon Landau of Rolling Stone who, somewhat ironically, had written for Boston After Dark. In an April 1968 article headlined “The Sound of Boston, Kerplop,” he called Ultimate Spinach “pretentious,” The Beacon Street Union “inept” and Orpheus “shlock.” On the other hand, some reviews were quite favorable: a critic for Cash Box who saw Phluph perform at the Psychedelic Supermarket came away very impressed.

Years later, Boston-based rock critic Brett Milano called the Bosstown Sound initiative “one of the more spectacular flops of its era.” The problem, he wrote, was that record companies were seeking any groups that sounded like they would appeal to the hippie culture of the late 1960s, and many of the bands they signed were simply not that good musically. Former Tea Party manager Steve Nelson, who booked many of the acts at the famed venue, has said there never was a “Bosstown sound” as such, just different bands playing different kinds of music resulting in the eclectic mix of rock, blues, R&B, jazz and folk for which Boston became known. Many of the musicians had loads talent and a devoted local following; they just weren’t ready to have a national spotlight shined on them, Nelson says.

Orpheus, Ultimate Spinach successes

By late 1968, MGM reported to the trades that Orpheus and Ultimate Spinach had done especially well sales-wise, having sold over $1.2 million worth of singles and albums. Orpheus’ debut disc had sold 60,000 copies and “Can’t Find the Time” had sold 100,000. Some of the Bosstown Sound bands prided themselves on not having a commercial sound but one of them, Ultimate Spinach, managed to carved out a niche, their first album selling 110,000 copies. Orpheus and Ultimate Spinach turned out to the most successful Bosstown Sound bands; the majority of others were unable to gain any significant national traction.

Petering out, Ending

It wasn’t surprising that when a new president took over at MGM, any bands that weren’t selling well or didn’t fit the label’s new image were dropped. Eventually, the same fate happened to the bands signed by ABC and Elektra. For example, Earth Opera, which had received positive reviews in trade publications like Billboard and found airplay on quite a few FM stations, still had the same problem as many of the Bosstown Sound bands: they didn’t make the charts. And since many of the labels that signed them lost money by doing so, nobody was shocked when the record companies dropped the bands. By 1969, for all intents and purposes, the Bosstown Sound was over.

Legacy

While Alan Lorber and the various record companies might have misjudged what the youth culture wanted, some of the Bosstown Sound bands did have tremendous talent and some of their songs sound terrific to this day. Had those groups been allowed to stand on their own, without being artificially tied to a “sound,” all of them might have been significantly more successful commercially on a national scale.

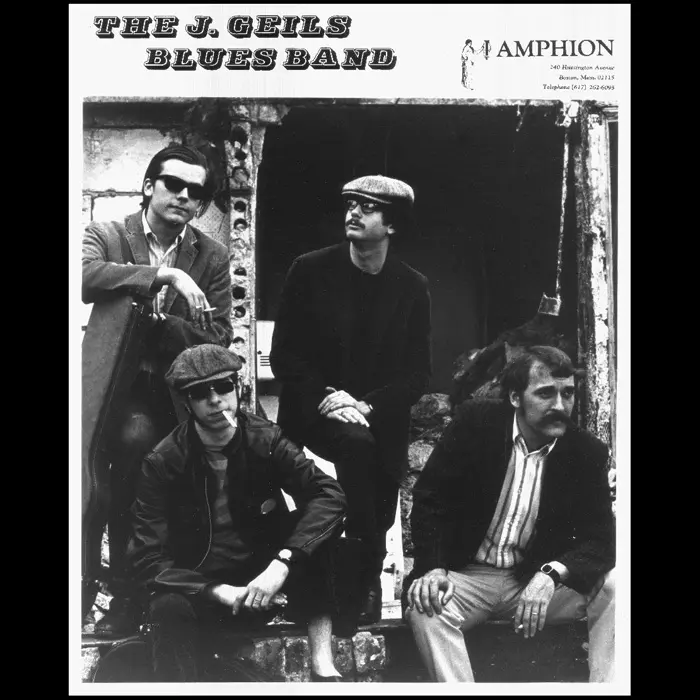

And let’s not forget: Since the Bosstown Sound met its demise, many huge hit singles and albums have come from Boston and the greater-Boston area from The J. Geils Band, Donna Summer, Aerosmith and The Cars to New Edition, New Kids on the Block and (of course!) Boston.

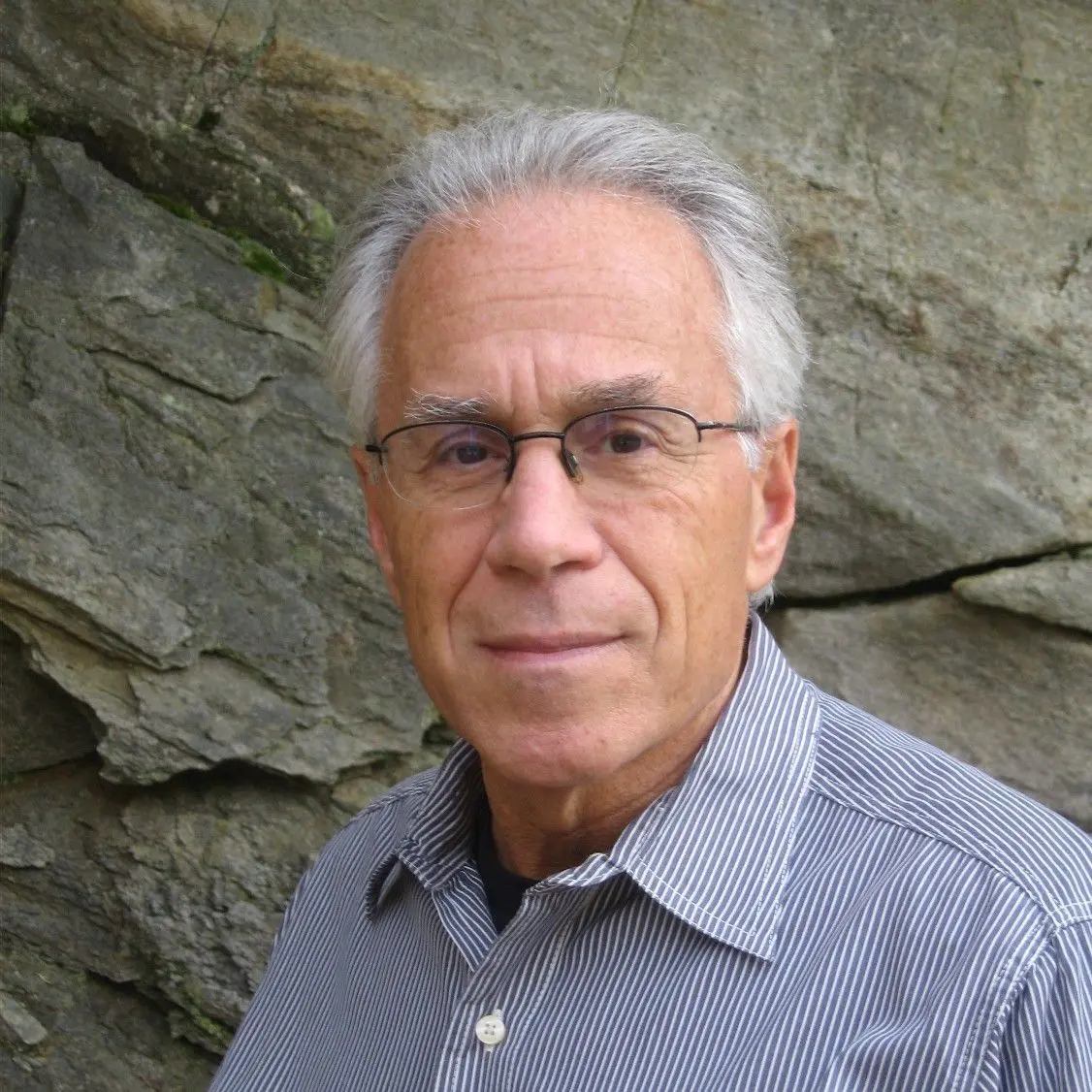

(by Donna Halper)

Former deejay, music director and radio consultant Donna Halper is a Boston-based historian who has spent over three decades as a professor, teaching media-related courses at Emerson College, the University of Massachusetts and Lesley University. She’s the author of six books including Boston Radio: 1920-2010 (Arcadia Publishing, 2011) and has written articles for a variety of publications. Dr. Halper was inducted into the Massachusetts Broadcasters Hall of Fame in 2023.