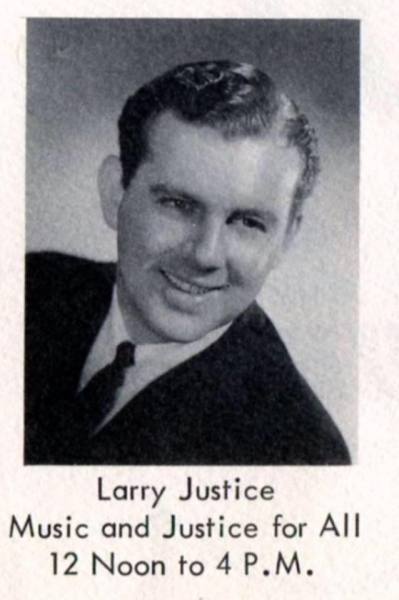

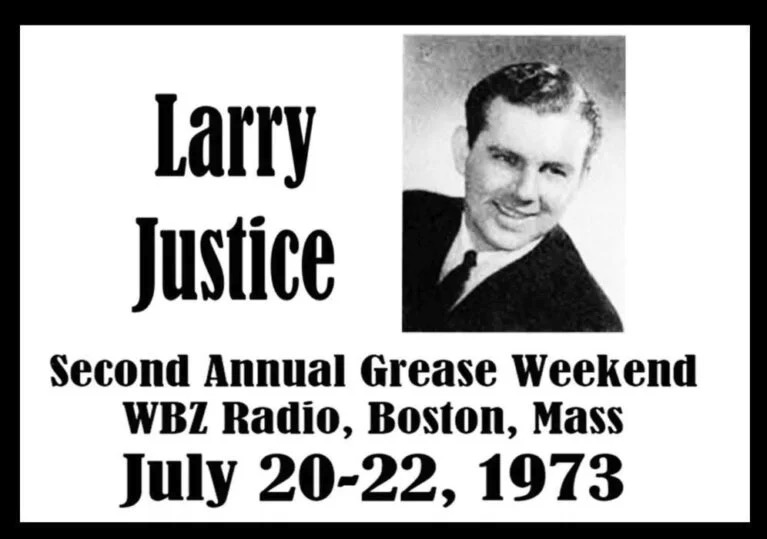

Larry Justice

If you lived in Boston in the 1960s and 1970s and listened to local radio, then you surely remember Larry Justice, the wildly popular deejay who brought his listeners into “the Halls of Justice,” first on WMEX and then on WBZ. His story is familiar to anyone who loves radio in that he knew from the time he was a kid that he wanted to be on the air.

Born Lawrence Kirk Justice on September 20, 1939, in Little Rock, Arkansas, his parents, Felix and Jeanette, ran a local grocery store and sometimes he worked there after school. But he never had any interest in joining the family business; he just wanted to be a deejay. And that’s exactly what he’s done – for over six decades.

KBBA, KGHI, “Kirk Justice”

Justice landed his first radio job in 1955, when he was a student at Central High School, working the early-morning shift at KBBA in Benton, about a 30-minute drive from Little Rock. The school allowed him to organize his class schedule so that he could sign the station on and do a couple of hours before returning to finish his classes. As radio grew in importance in his life, Justice left high school before graduating (later completing a GED) to do the afternoon shift at KGHI in Little Rock at KGHI. During his time in Benton and Little Rock, he used the on-air handle “Kirk Justice” (Kirk was also his father’s middle name).

KNLR, KAJI

In April 1957, Little Rock got a new station, KNLR (the call letters referring to “North Little Rock”) and the station hired Justice to do an afternoon shift; he was soon promoted to program director. In late December that year, he and his high school sweetheart Beverly got married. They would go on to have two children, a son and a daughter and, in an industry where relationships come and go, the two were still happily married over six decades later.

In late 1958, Justice returned to KGHI and he was still there when the station changed its call letters to KAJI in June 1959. He has positive memories of being on the air in Little Rock during rock ‘n’ roll radio’s formative years, he says, because even though it was a small market, the city’s top-40 stations had a reputation for taking chances on up-and-coming, little-known artists.

Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis friendships

And Little Rock could not have been in a better location to do that since it was about a two-hour drive from Memphis, where a burgeoning country-rock scene was emerging thanks to exciting young performers like Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash and Jerry Lee Lewis. Getting airplay was crucial for these up-and-coming artists, and the record promoters would often bring them by to visit radio stations in Little Rock.

That’s how Justice first met and befriended the performers. And the friendships he developed stood him in good stead throughout his career. For example, he and Elvis kept in touch over the years and Justic went backstage to see him whenever he was performing in Boston. In the early ‘70s, he emceed one of Johnny Cash’s Boston concerts.

Military service, WPCG, “Barefoot Larry Justice”

In late 1959, when Justice was becoming quite an influential deejay in Arkansas and it neighboring states, he was drafted into the army. He served in the public information office of Fort Leonard Wood in Rolla, Missouri, where he created a radio division and he and several other announcers had their own programs, airing on-base events and other news. Once his military service ended, Justice decided it was time to seek work in a bigger, more metropolitan market. After applying for a job at WPCG in Washington, DC, that he’d seen posted in a broadcasting industry trade publication, Justice joined the station in early 1962, hired by General Manager Bob Howard. At age 22, he was on the air in one of the top 10 markets in the US.

Howard wanted him to change his name from “Kirk” to “Larry” and gave him the on-air identity “Barefoot Larry Justice, friend of the Barefoot Housewives,” which refers to a common expression of that era (about a decade before the women’s movement) when some men said (either jokingly or seriously) that a wife should be kept “barefoot and pregnant.” There’s no evidence that Justice agreed with this sentiment – he said later that he was never fond of the on-air name – but his on-air slot was on weekday afternoons ( “housewife time,” as it was known in the radio industry at the time) and the moniker reflected the beliefs of many in mainstream culture.

Raise-demanding stunt, WIBG

In that era of “personality radio” and top-40 rock deejays, Justice began to build a strong following in his adoptive city. He also drew national attention for a clever stunt he masterminded: On August 6, 1962, he locked himself in the studio and demanded the raise he said he had been promised, refusing to come out while playing the same record repeatedly for several hours (a popular novelty tune, “Presidential Press Conference”). After some of Justice’s fans gathered in front of the station to express support, management agreed to his demands.

At the time, newspaper reporters who covered the story thought it was totally spontaneous, but it had actually been a promotional ploy – a very successful one – orchestrated by the station’s program director. It led to considerable publicity for WPGC in and outside the greater DC area and elevated Justice’s profile dramatically.

Justice’s next move to WIBG in Philadelphia, at top-40 powerhouse, where he worked as a deejay and music director alongside well-known radio veterans like Hy Lit and Joe Niagara. He remained in Philly from March 1963 to February 1965. Meanwhile, WPCG owner Maxwell “Mac” Richmond wanted to hire him in Boston at one of his other stations, the rock-centric WMEX, which had been airing a top-40 format since 1957.

Joining WMEX

On Valentine’s Day 1965, Justice stared his new job as one the “WMEX Good Guys,” eventually becoming the station’s morning deejay. While some people over the years have said Mac Richmond was nearly impossible to work for due to his caustic personality and unreasonable demands, Justice’s memories of him are kind: “Mac gave my talent a direction. He took what was there and molded it,” he said. “I will forever be grateful. He could be difficult to get along with, but he also could bring out the best in an announcer.”

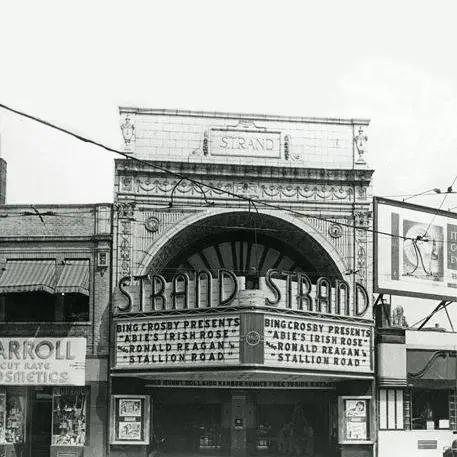

As in the other cities where Justice had worked, Boston’s top-40 stations often broke new music or introduced the audience to up-and-coming artists. “You never knew who would show up the station,” Justice said. “Promoters were always bringing artists to the WMEX studios, especially if they were playing locally.” And while the format didn’t permit long interviews, he and the other deejays could still say hello, make some small talk and help to support the performer and announce the upcoming concert. Sometimes, Justice was asked to emcee, such as when Little Anthony and the Imperials appeared at the Strand Theater in Dorchester in September 1965.

Record hops, Leaving WMEX

Although Justice and station owner Mac Richmond got along well, the pay at WMEX wasn’t particularly high and he and several of the other announcers hosted record hops to supplement their income. Justice used a local band named Jimmy and the Jesters at all his dances since they were very popular with audiences despite never having any top-40 hits.

While he enjoyed doing record hops, he needed a significantly larger salary from WMEX to support his family but in the four years that he worked there he’d been given just one small raise. In late 1968, realizing that no additional money was forthcoming, he quit despite a non-compete clause in his contract that prevented him from being on the air in Boston for six months after his departure.

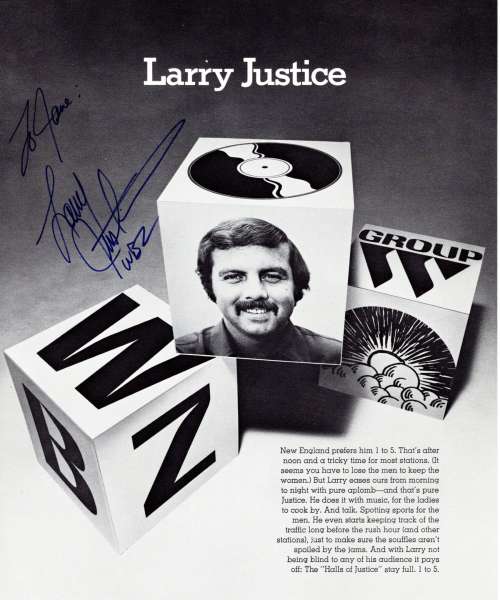

Joining WBZ, Leaving WBZ

After leaving WMEX, Justice joined WDRC in Hartford (a commute of 80 miles each way from his home in Wellesley, Massachusetts), covering the mid-day shift. In May 1969, when the noncompete agreement with WMEX expired, he joined the team at WBZ doing an evening show and some vacation fill-ins. By August, he’d moved to the afternoon shift that he occupied for the next five years. Since ‘BZ was broadcasting an adult-contemporary format at the time, not a rock-centric top-40 one, among the performers who visited the studio were Sonny & Cher, Wayne Newton, The Carpenters and Tom Jones; Justice was the emcee at one of The Carpenters’ Boston concerts.

In late 1974, WBZ’s new management made a number of changes, one of them being that they moved Justice from weekday evenings to weekends. Frustrated by the sudden switch, Justice walked away from WBZ about six months later, in April 1975, and spent a few months working weekend shifts at WHDH before becoming a full-time voice-over announcer.

WROR, WCIB

For the next several years, he worked for a talent agency in New York, voicing local and national commercials. But while he was paid well for his efforts, he missed being part of Boston radio so in January 1980 he joined WROR-FM, doing the afternoon drive. After being at the station for more than two years, however, he found himself out of a job in November 1982. While he was still making money by voicing commercials – he was heard on ads for the Jordan Marsh department store chain and Valle’s Steak House, among others – he decided that his main goal was to own a radio station.

In June 1983, he purchased WCIB-FM in Falmouth, on Cape Cod, for $2 million (about $6 million in 2024). He implemented an adult-contemporary format, aired lots of sports in addition to music and was the station’s morning show host for four years, part of a team that included weatherman Harvey Leonard and Fred Cusack reporting on sports. During the rest of the decade, Justice purchased stations in Jacksonville and Fort Myers, Florida; Stowe, Vermont; and Portsmouth/Exeter, New Hampshire.

Later activity, Return to WMEX

Justice sold off his radio properties in the early 1990s, and retired to Naples, Florida, where he opened a real estate business. Still blessed with a deejay’s voice, however, he always considered returning to the airwaves, just for fun. And in May 2020, when he was 80 years old, that’s exactly what he did, and on WMEX of all places, the station having returned that year after 44 years off the air under those call letters.

Since then, he’s hosted his own 10am-2pm show on weekdays, broadcast from his Florida home, during which he plays hits from the ‘50s, ‘60s, ’70s and ‘80s. Today, Justice co-owns the station with his business partner Tony LaGreca through their company, L&J Media.

(by Donna Halper)

Former deejay, music director and radio consultant Donna Halper is a Boston-based historian who has spent over three decades as a professor, teaching media-related courses at Emerson College, the University of Massachusetts and Lesley University. She’s the author of six books including Boston Radio: 1920-2010 (Arcadia Publishing, 2011) and has written articles for a variety of publications. Dr. Halper was inducted into the Massachusetts Broadcasters Hall of Fame in 2023.