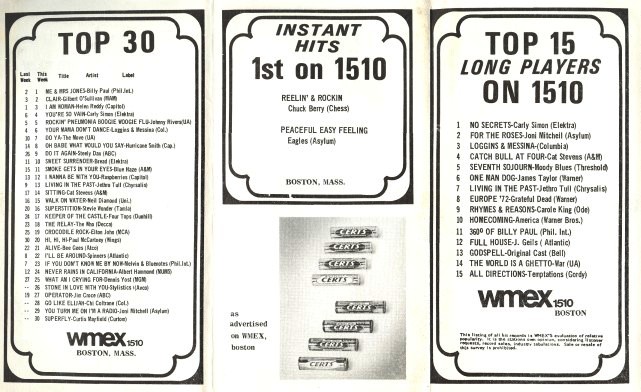

WMEX

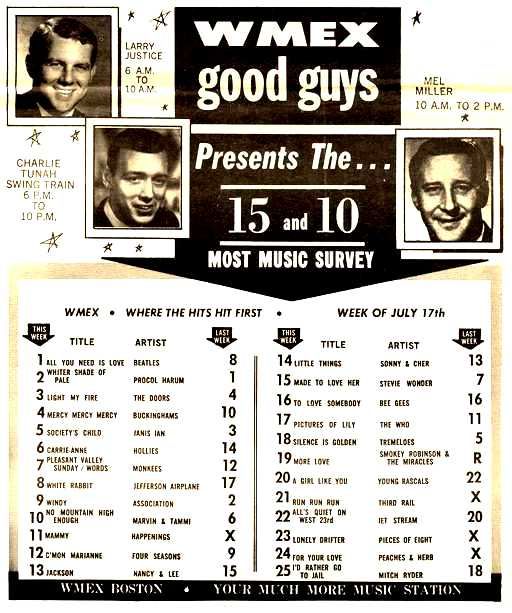

In 1955, when rock ‘n’ roll was becoming a significant presence on mainstream American radio, Billboard magazine published its first rock-centric singles chart, the Top 100 (renamed the Hot 100 in 1958). In 1956, it introduced its first rock-centric albums chart, Best Selling Popular Albums (renamed the Billboard 200 in 1992). And in 1957, WMEX became the first Boston-area station to adopt a rock-centric top-40 format, beginning its nearly 20-year run as a regional rock ‘n’ roll bellwether, an on-air Billboard of sorts at 1510 AM.

Like the editors at Billboard, which started running charts for big-band singles in 1940, R&B singles in 1942 and country singles in 1944, WMEX’s owners were certain that rock ‘n roll was not a fad like many of the station’s older listeners insisted; it was the future of popular music. And by embracing the amped-up new genre years before rivals WRKO and WBZ switched to a top-40 format, WMEX became the go-to spot on the dial for poodle-skirt-clad young women and ducktail-sporting young men in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s and for many in the paisley-print and tie-dye-wearing crowd from the mid-‘60s to the mid-‘70s.

And as of 2020, WMEX is back. While it used a swath of other call letters and formats between 1976 and 2017 – talk shows, sports, adult contemporary, adult standard, Spanish-language and contemporary Christian – the station has returned to the airwaves with an oldies format, playing hits from the ‘50s, ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s. For throngs of Bostonians across several generations, the recent resurfacing is proof that “music’s good old days” – an expression that prompts instant eye rolls from most Millennials and virtually all GenZers – really were as good as they say they were. Heck, maybe even bettah.

FOUNDING, 1930S

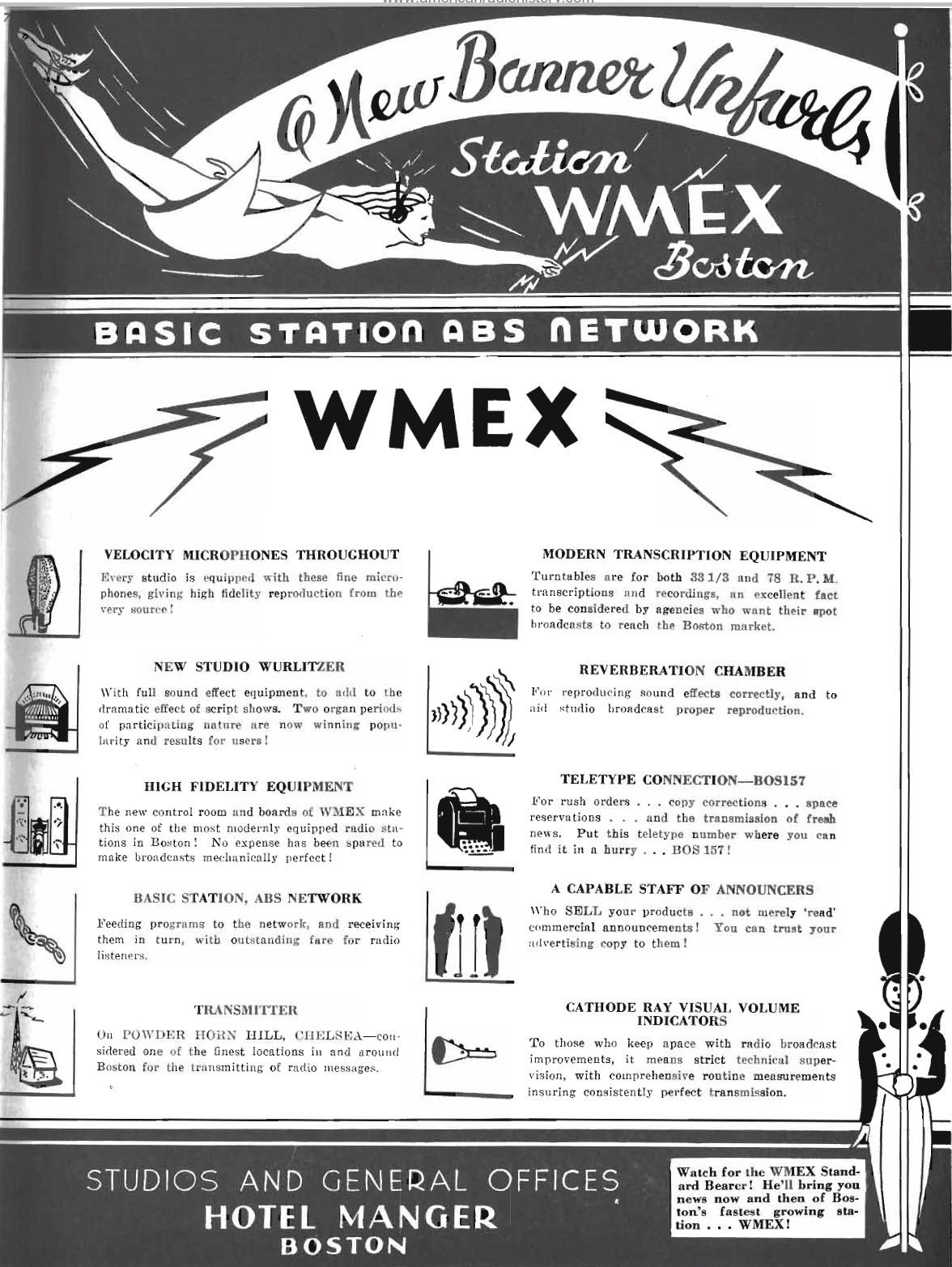

Operating under a limited-commercial license, WMEX made its first broadcast on October 18, 1934, four months after passage of the Communications Act, which established the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). There were about 25 other stations in the Boston area at the time and radio had become a central part of American life, particularly with the Great Depression having sent the unemployment rate to 25% by the time ‘MEX went on the air.

Owned by brothers Bill and Al Poté, the station transmitted at 1500 AM – 250 watts in the daytime and 100 watts at night – from an industrial area in the Powder Horn Hill district of Chelsea. The studios were in Boston’s plush Hotel Manger, a 17-story building with direct access to North Station in which many of the era’s entertainment icons stayed when appearing at Boston Garden, including Roy Rogers, Arthur Godfrey, Gene Autry and Rudy Vallée.

In December 1934, the Department of Commerce issued WMEX a commercial broadcasting license. A year later, in January 1936, the station’s studios moved to 70 Brookline Avenue in Boston and in 1939 WMEX was allowed to increase its night power from 100 to 250 watts. During the ’30s, broadcasts consisted of classical, jazz, news, horse racing and “ethnic programming,” meaning shows that targeted non-white listeners and minority communities.

1940-1957, JOHN KILEY, NAT HENTOFF, JOE SMITH

In September 1940, the station moved its transmitter and studios to Quincy, along the banks of the Neponset River. In late 1940 WMEX was authorized to increase its daytime signal to 5,000 watts and in March 1941, as part of the North American Regional Broadcasting Agreement, the station moved to 1510 AM, where it’s remained ever since.

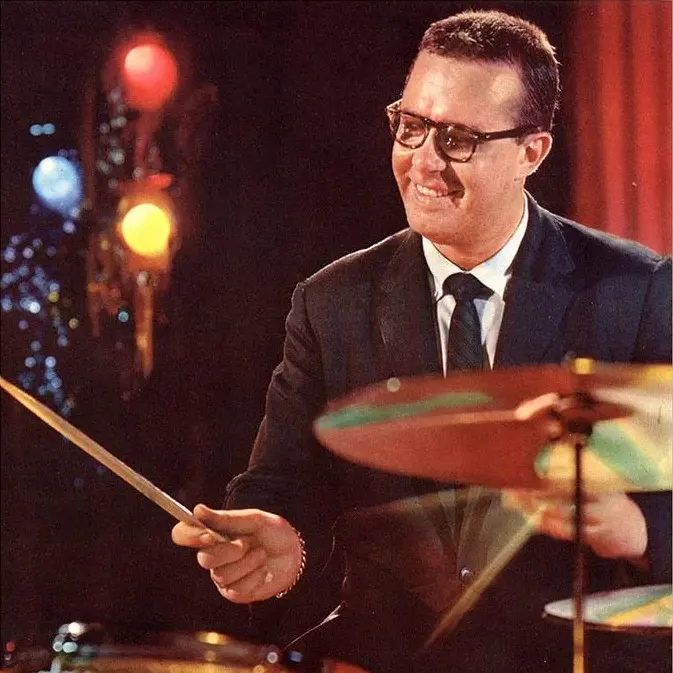

In the ‘40s, WMEX expanded its musical offerings and often aired live music from outside its Quincy studios, especially after becoming an Associated Broadcasting Corporation affiliate in mid-1945. One of the station’s first on-air musical stars was future Fenway Park and Boston Garden organist John Kiley, WMEX’s music director from 1934 to 1956, who hosted three daily programs in the early/mid-‘40s including Letter-Quest, for which listeners mailed in their requests – a groundbreaking concept at the time.

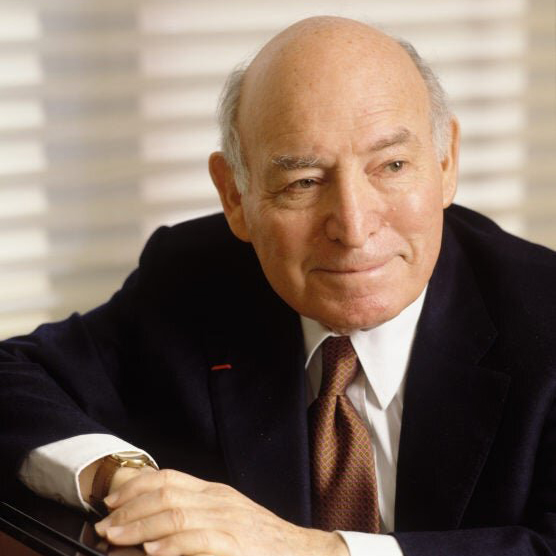

Among the station’s notable on-air personalities from the late ‘40s to the mid-‘50s was celebrated jazz critic and native Bostonian Nat Hentoff, who hosted two WMEX radio shows, JazzAlbum and From Bach to Bartók, and dozens of live broadcasts from inside George Wein’s Storyville nightclub, including ones of Billie Holliday, Dave Brubeck, Ella Fitzgerald, John Coltrane, Stan Getz, Charles Mingus, Sarah Vaughan and Charlie Parker. From 1950 to 1957, future Warner Bros. president, Elektra/Asylum chairman and Capitol-EMI CEO Joe Smith, a Chelsea, Massachusetts, native, was a WMEX jazz deejay.

TOP-40 ERA, ARNIE GINSBURG, OTHER NOTABLE PERSONALITIES

In 1957, the era for which WMEX is best known began when the Poté brothers sold WMEX to the Richmond brothers. One of them, Maxwell “Mac” Richmond, an advertising executive from Philadelphia who’d bought WPCG (Washington, DC) in 1955, spearheaded the station’s format change from jazz to rock ‘n’ roll in September that year, making WMEX one of the first stations in the US to take what was then considered a daring leap into the unknown.

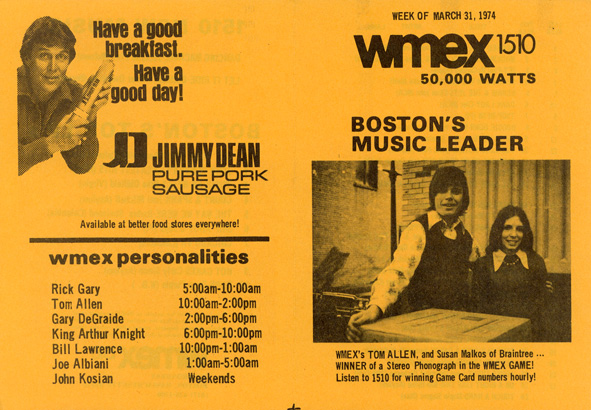

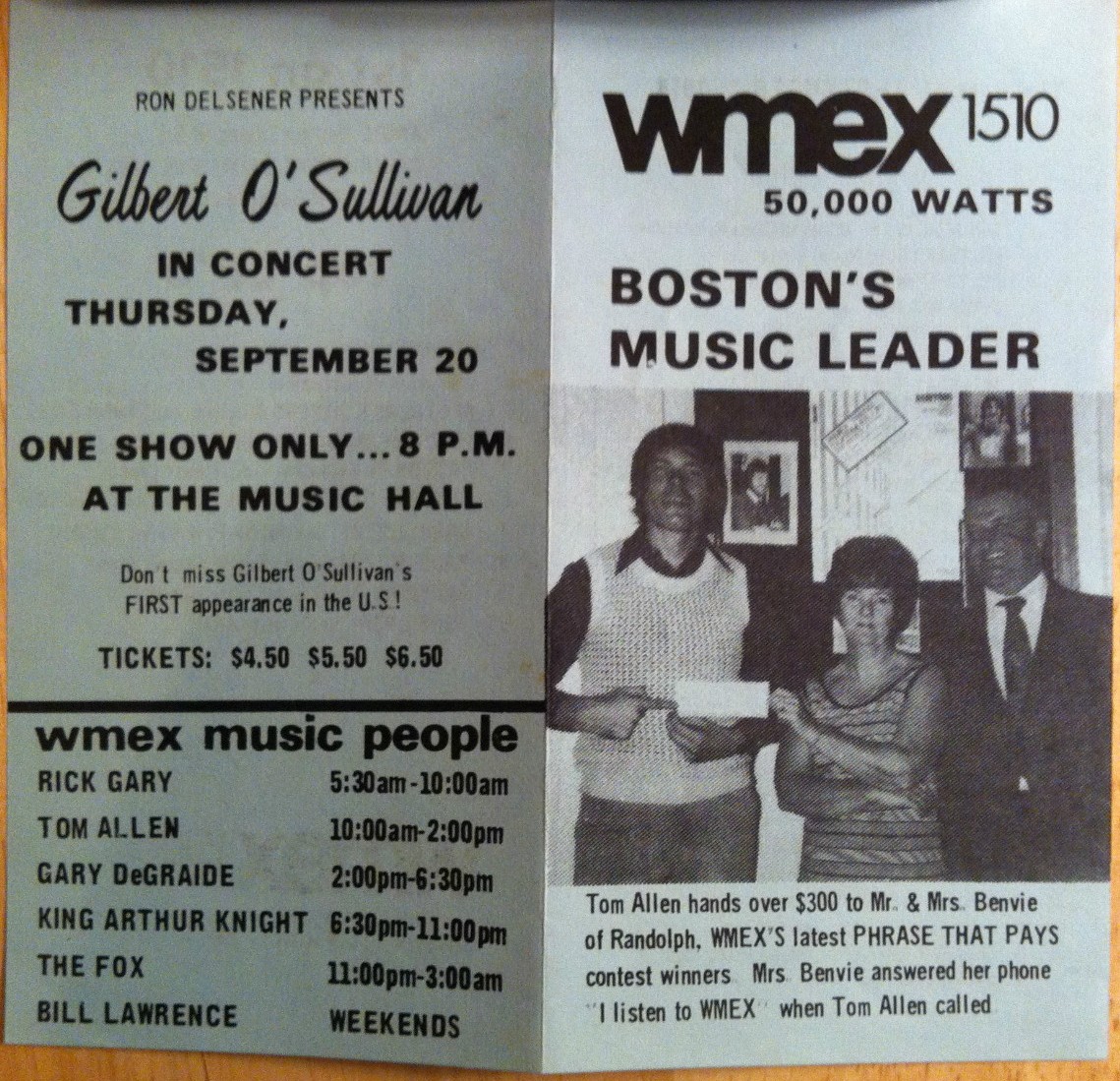

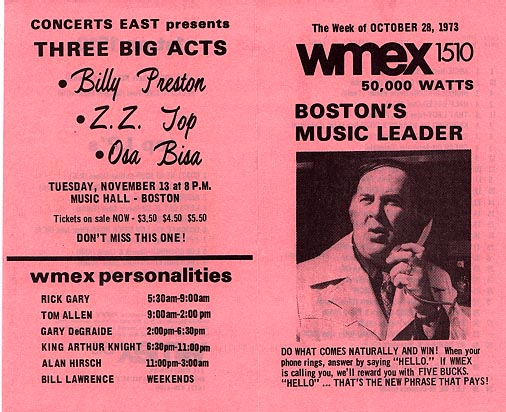

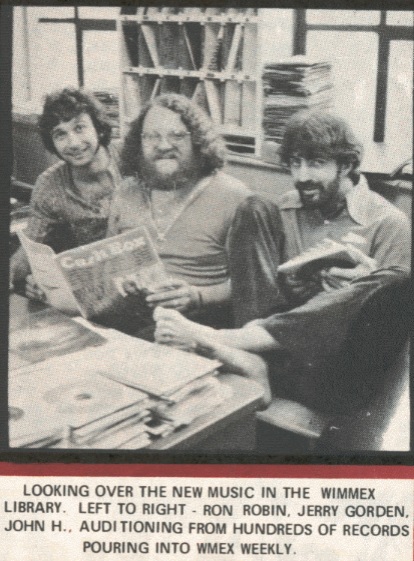

While his micromanagement approach and notoriously toxic personality made him a difficult boss reportedly, Richmond was widely respected for his ability to hire exceptional on-air talent. One of his first moves as station owner was to recruit deejay Arnie “Woo Woo” Ginsburg from local rival WBOS (now WUNR); Ginsburg stayed with WMEX until 1967, becoming a bona fide radio legend in the process. The list of other on-air personalities during the station’s top-40 heyday is a who’s who of pioneering New England rock jocks including Larry Justice, Tom Allen, Rick Gary, King Arthur Knight, Bill “The Jones Boy” Jones, Mel Miller, Dan Donovan, Joe Albiani, Charlie Tuna, Jack Gale, J.J. Jeffrey, Melvin X. Melvin, John Kosian, Alan Hirsch, The Fox, Bill Lawrence, Ron Robin, Jerry Gordon, Bud Ballou and Gary DeGraide.

In addition to landing top disc-spinners, Richmond established ‘MEX as a talk-radio pioneer in 1957 when he hired Jerry Williams to host a nighttime listener call-in show, expanding the station’s audience from teenage rockers to issues-conscious adults. Other Massachusetts stations had aired talk shows before then, but Williams’ was the first in the area to make listeners’ voices a regular part of the broadcast (about five years before the idea caught on at other stations and 10 years before it became common). Williams stayed with ‘MEX until 1965 and among his most regular guests was Malcolm X, who lived in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood from his early teens to his early 20s.

LATE 1960S-1975, DICK SUMMER

In the late ‘60s, with public tastes shifting toward new rock subgenres and the rise of rock-centric FM competitors like WBCN, WMEX faced unprecedented challenges to its market dominance. The station’s biggest AM rival was WRKO, which aired at 50,000 watts at all hours; ‘MEX started broadcasting at 50,000 watts in the daytime in 1969 but still aired at only 5,000 at night, giving ‘RKO a massive advantage in the rapidly expanding Boston suburbs.

In an attempt to gain a competitive edge, the station hired 34-year-old Dick Summer (who’d spent the previous six years at WBZ) as its new program director in May 1969. With a psychology degree from Fordham University, Summer had a keen understanding of listener demographics and the cultural zeitgeist, establishing an in-studio ethos he called “the human thing” under which the station played cuts with lyrics he thought would resonate with the people on an emotional level; the concept was in perfect alignment with the introspection and sensitivity of the burgeoning singer-songwriter era. On his own nighttime show, Lovin Touch, he mixed music and poetry (including some of his original poems),

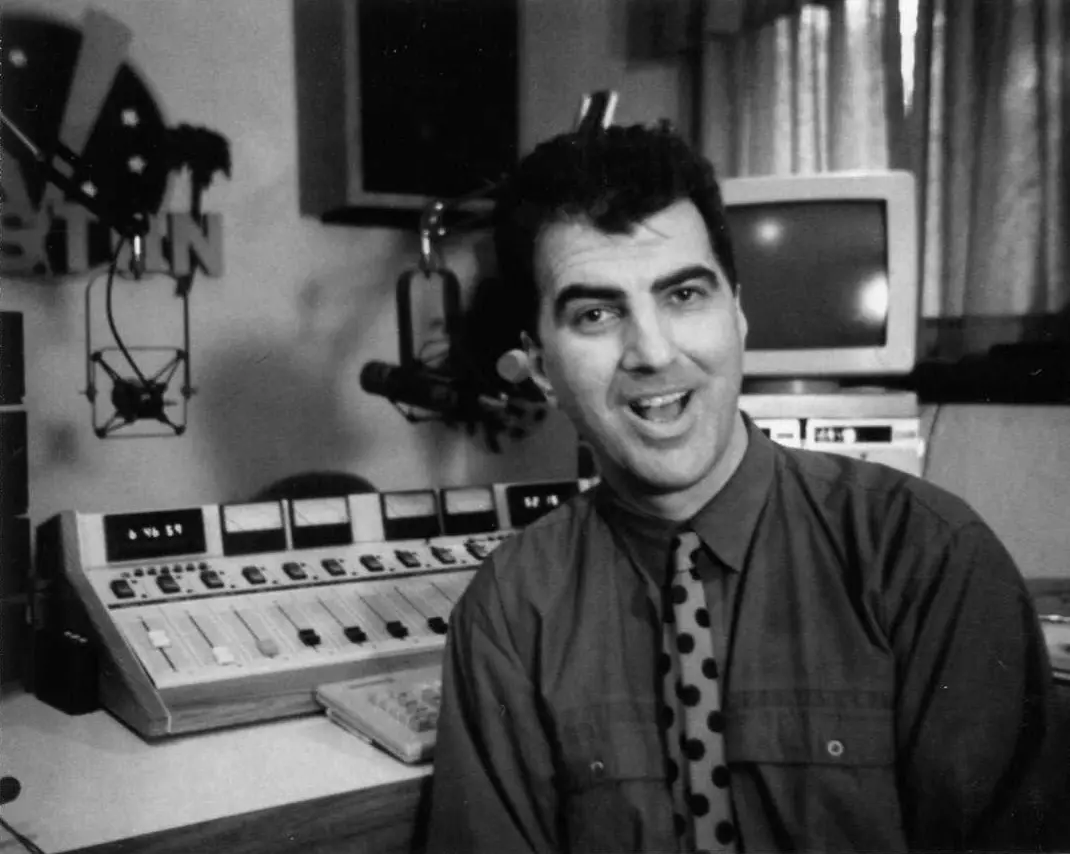

AMERICAN TOP 40, JOHN GARABEDIAN, J.C. CONNORS

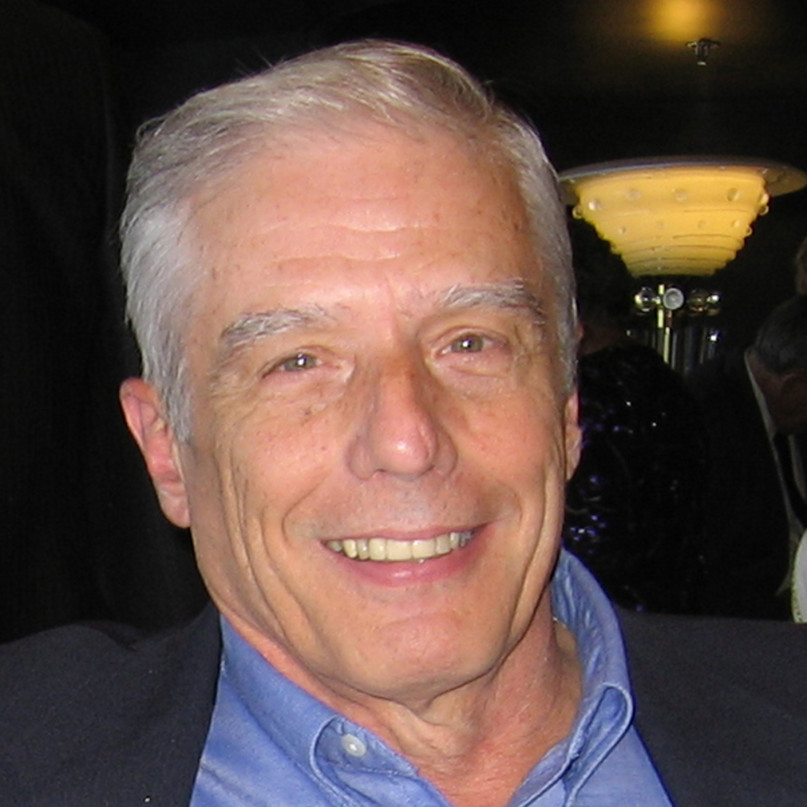

In July 1970, WMEX was one of just seven US stations to air the debut episode of the nationally syndicated show American Top 40. Summer left the station about a year later, returning to WBZ in mid-1971, and the man he’d hired as ‘MEX’s afternoon deejay, John Garabedian, took over as program director, immediately rebranding the station as “The New Music Authority” in an aggressive effort to challenge ‘RKO.

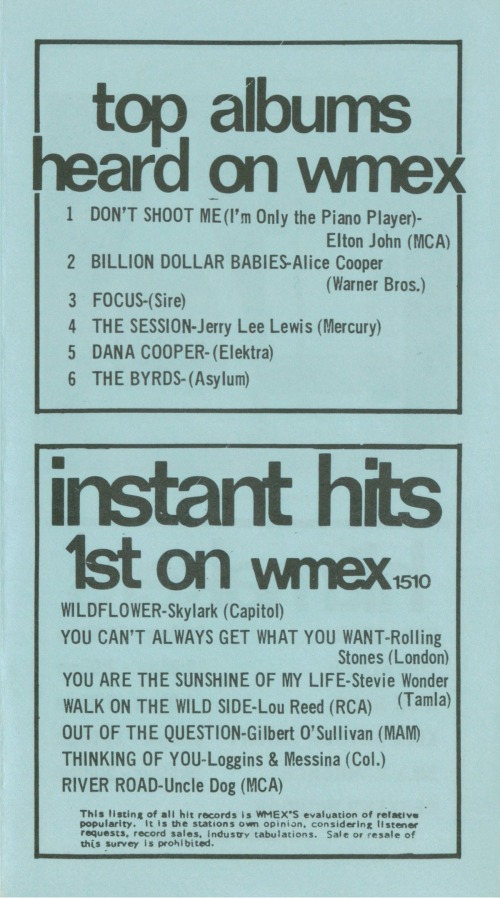

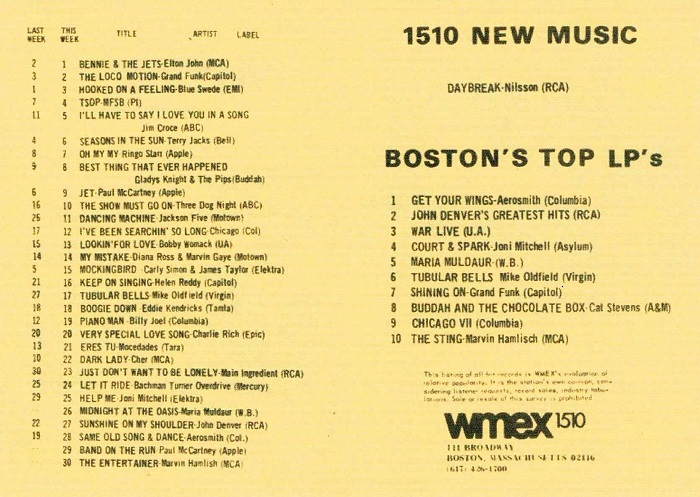

Rather than relying solely on the Billboard charts for guidance, Garabedian took a hands-on approach, airing tracks that he personally believed would become popular, not just those that were already popular. Among the tunes ‘MEX broke during his tenure were Rod Stewart’s “Maggie May,” The Moody Blues’ “Nights in White Satin,” The Five Man Electrical Band’s “Signs,” Lee Michaels’ “Do You Know What I Mean,” Paul and Linda McCartney’s “Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey,” Jonathan Edwards’ “Sunshine,” Ten Years After’s “I’d Love to Change the World” and The J. Geils Band’s “Looking for a Love.”

Garabedian’s innovative playlist-crafting efforts led to a substantial ratings boost but were extremely short-lived due to an event nobody saw coming: In October 1971, a mere five months after Garabedian started coloring outside of the proverbial Billboard lines, 57-year-old station owner Mac Richmond had a fatal heart attack and his brother took full control of the station, pulling back on Garabedian’s initiatives; within a month, Garabedian was sent packing.

In a January 1972 piece titled “Boston Tests New Music & Flunks Out: WMEX and WRKO Battle for Radio Listeners,” Rolling Stone’s Timothy Crouse gave Garabedian credit for his efforts but said ‘RKO simply outplayed him. “It was only a five-month battle, but it was a great show while it lasted,” he wrote. “The war was started by John H. Garabedian, the program director of WMEX, a bottom-of-the-heap top-40 station. With the tactical abandon of an underdog, [he] innovated right and left, doubled the station’s ratings and nearly outflanked the forces of WRKO. But WRKO, firmly entrenched as Boston’s #1 top-40 station, adopted some of John H.’s changes, geared up for a major offensive and fought to stay on top.”

From 1972 to 1975, ‘MEX retreated from the top-40 battle, adopting a middle-of-the-road, album-track-oriented format. During that time, deejay Jim “J.C.” Connors helped send a number of cuts to gold in the charts including Chuck Berry’s “My Ding a Ling,” Mouth and MacNeal’s “How Do You Do,” Chi Coltrane’s “Thunder and Lightning,” Wayne Newton’s “Daddy Don’t You Walk So Fast” and Joe Simon’s “ Power of Love.” Connors is widely known as the inspiration for Harry’s Chapin’s 1973 hit “WOLD.”

1976-2017: MULTIPLE CALL LETTERS, FORMATS

In 1976, WMEX removed music from its format altogether, becoming sports- and talk-based, and in 1978 the call letters changed to WITS (“Information, Talk and Sports”). In 1981, when the station moved its transmitter from Quincy to Waltham, WITS began airing at 50,000 watts both day and night and in 1982, when the station’s then owner, Mariner Communications, fell into financial difficulties, it abandoned the talk and sports format.

For the next 25 years, the station went through a number of formats, starting in 1983 with adult contemporary (as WMRE). Other formats included soft adult contemporary (as WSSH), country (as WKKU), Spanish-language and Christian music (as WNRB). From the early ‘90s to 2007, it broadcast an all-sports format (as WWZN) and from 2008 until 2014 it aired talk shows and sports (as WUFC). In November 2014, the station reverted to the call sign WMEX and in 2015 two Saturday-night oldies show debuted, one hosted by Jim Callahan and Chris Porter and another by Jimmy Jay. In mid-2015, North Carolina-based Daly XXL Communications purchased the station for $175,000.

2017-2019 RADIO SILENCE, 2020 RETURN

In the spring of 2017, rumors began circulating that the station would be going off the air on June 30 since the lease on the Waltham transmitter was due to expire that day. And at 6pm on June 29, the rumors proved to be true; WMEX went silent and remained off the air until November 2019, when testing on a new transmitter began. The Waltham towers were dismantled in May 2018.

In December 2017, Ed Perry, owner of Marshfield Broadcasting, offered Daly XXL Communications $125,000 for the silent WMEX signal, saying he wanted to “bring back memories” of its ‘50s/’60s glory days; the FCC approved the deal in March 2018. “I’m excited about the prospect of helping to revive the station I grew up with and truly loved as a kid in Natick [Massachusetts],” Perry told Northeast Radio Watch at the time. “It should be fun and I’m sure there’s a lot of air talent around to fill the frequency with great music and memorable words.”

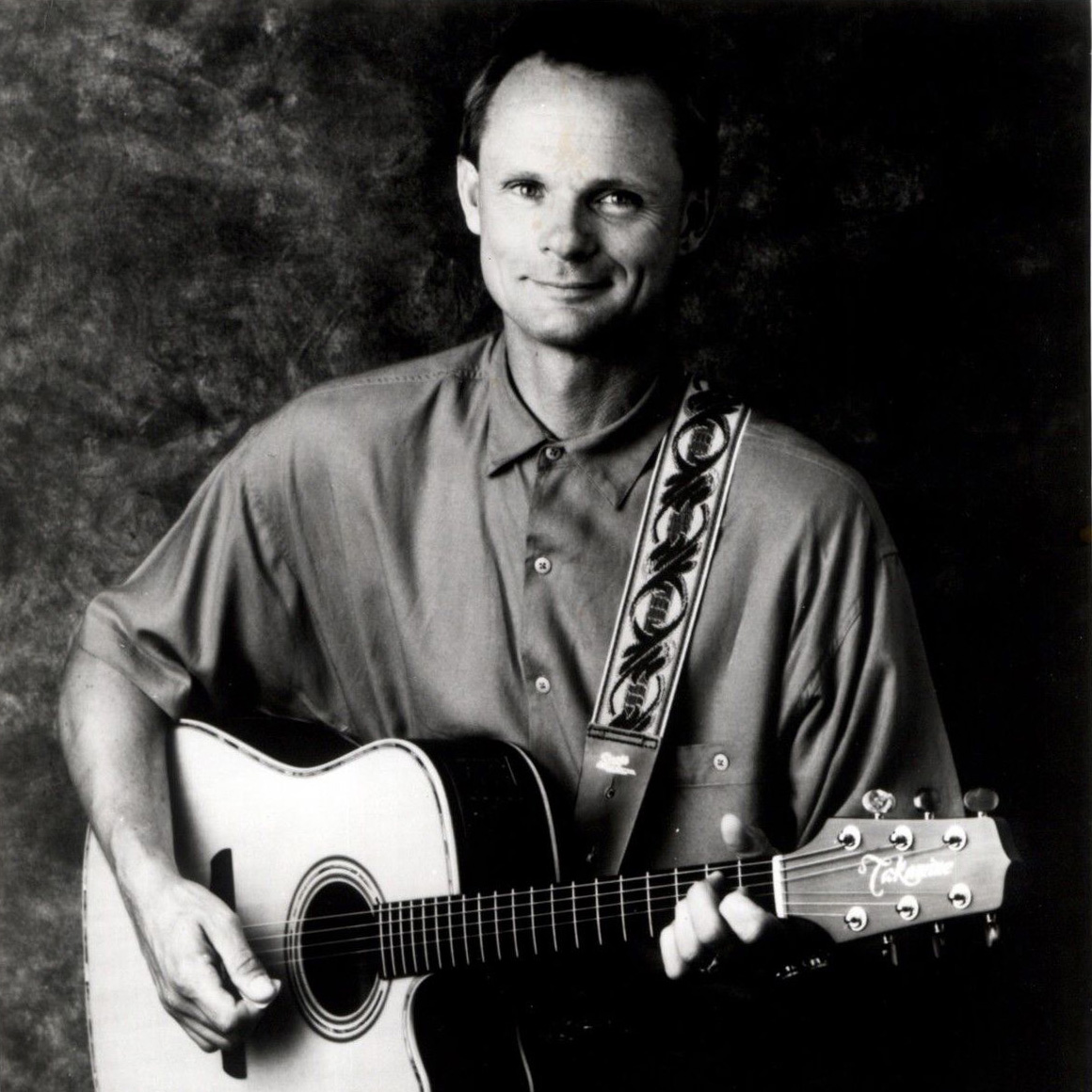

Using a transmitter on Riverside Avenue in Quincy, very close to where the old WMEX towers were, and new studios on Enterprise Drive in Marshfield, WMEX officially relaunched on May 18, 2020, at 9am, when none other than Boston radio legend Larry Justice – who manned the air at ‘MEX from 1965 to 1968 – played Three Dog Night’s “Joy to the World.”

CURRENT PROGRAMMING, OWNERSHIP

Currently, the station transmits at 10,000 watts for most of the day, 2,000 watts during critical hours – meaning two hours after sunrise and two hours before sunset, per FCC regulations – and 100 watts at night. The schedule includes shows hosted by Justice, Boston radio veteran Joe McMillan and Jimmy Jay (aka “The DJ of the Stars”); at night and on weekends, WMEX airs the syndicated music service MeTV FM. The station is currently owned by L&J Media, headed by Larry Justice and Tony LaGreca.

Asked for a comment on the day the station returned to the air, Perry talked about what WMEX meant to him and his fellow teenagers in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s. “It was the high school station,” he told the Quincy-based Patriot Ledger. “It was what you listened to.”

(by D.S. Monahan)