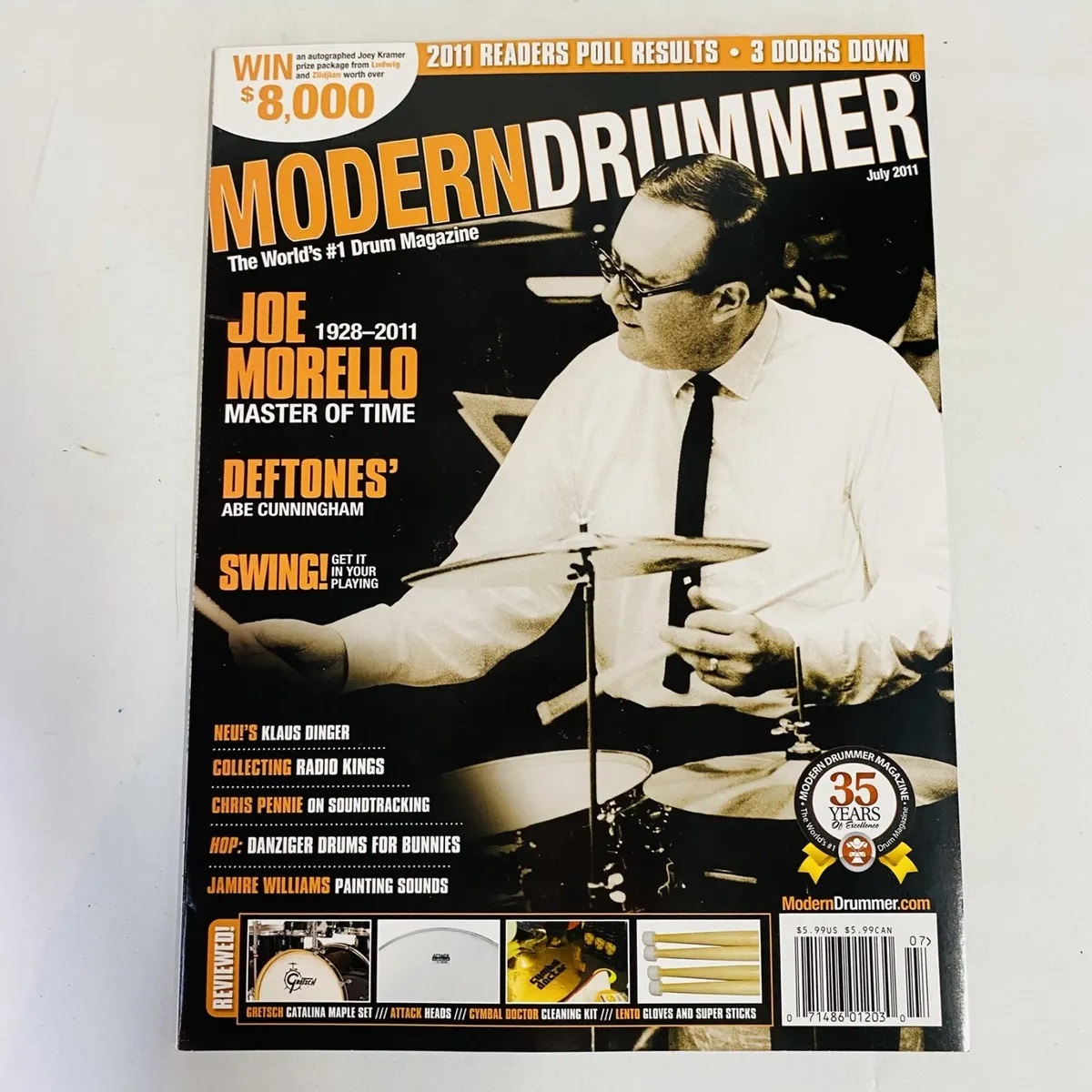

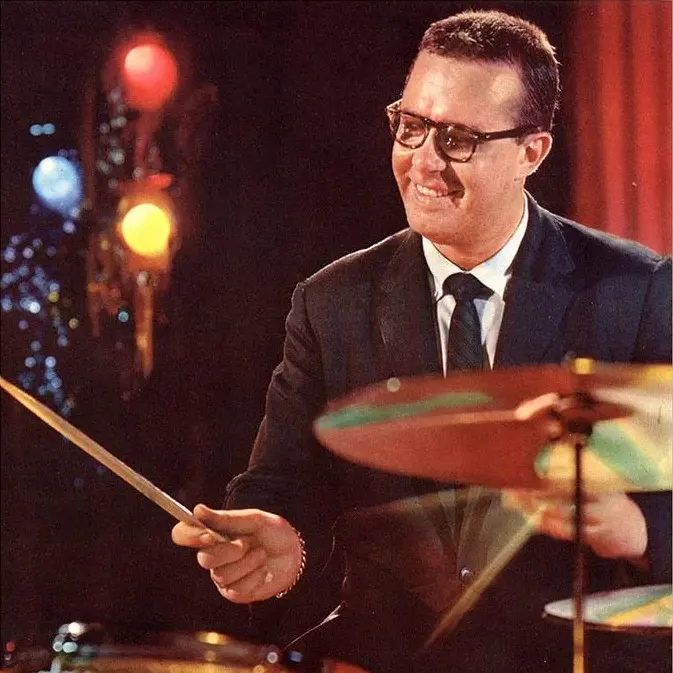

Joe Morello

In the Roaring ‘20s, the Jazz Age that’s been the setting of innumerable books and films began. By the mid-‘30s, it was finished, having morphed into the Big Band Era, which itself ended in the early ‘50s as what many considered fad – rock ‘n’ roll – commandeered the charts. But those Roaring ‘20s did produce something that changed jazz and popular music forever: an eye-popping collection of drummers that lifted their craft to unprecedented creative and technical heights, establishing their instrument as a musical centerpiece like never before. Among those trailblazing kitmen was Joe Morello, born July 17, 1928 in Springfield, Massachusetts.

A member of The Dave Brubeck Quartet who recorded several dozen albums with the group – including Time Out featuring “Take Five,” on which he plays one of the most famous drum solos in history – Morello’s sensational skills and singular style placed him shoulder-to-shoulder with contemporaries like Shelly Manne (b. 1920), Philly Joe Jones (b. 1923), Max Roach (b. 1924), Louie Bellson (b. 1924), Roy Haynes (b. 1925), Elvin Jones (b. 1927) and Alan Dawson (b. 1929). A towering presence in the history of modern drumming, his delicate, ever-tasteful approach inspired countless next-generation players including Jack DeJohnette (b. 1942), Tony Williams (b. 1945), Peter Erskine (b. 1954) and Terri Lyne Carrington (b. 1965).

MUSICAL BEGINNINGS

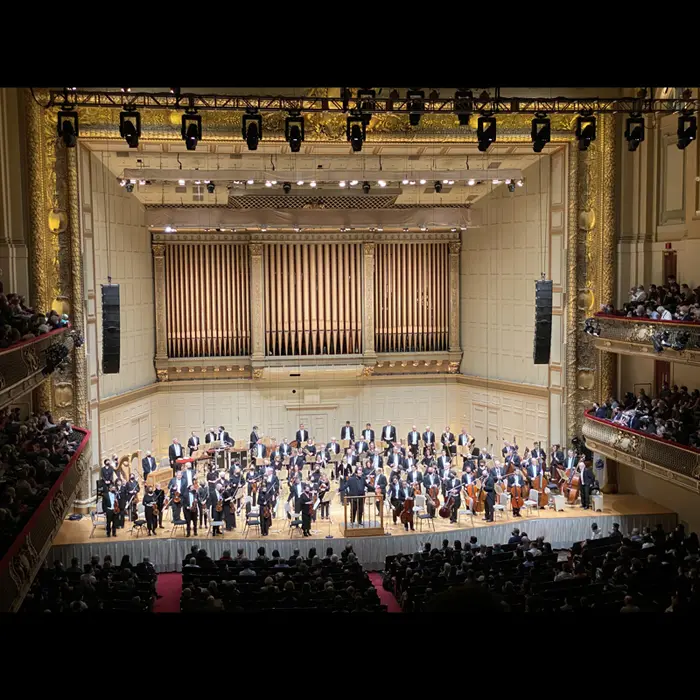

Born with severely impaired eyesight and often unable to play outside like other boys his age, Morello spent most of his childhood years indoors and his musical education began at age six when his parents encouraged him to study the violin as a hobby. Throwing himself into lessons and practice, at age 10 he debuted with the Boston Symphony Orchestra at Tanglewood as a soloist, followed at age 12 by another appearance with the BSO at Symphony Hall.

At age 14, however, after seeing Russian-American violinist Jascha Heifetz perform, Morello became so utterly discouraged that he stopped playing violin altogether, convinced that he’d never achieve such virtuosity. At age 15, after seeing drumming legend Gene Krupa (b. 1909) play at the Hartford Theatre, he shifted his focus to the drums – with his sights set on performing with a classical orchestra, not a jazz band – and started taking lessons from Joe Sefcik at the Pizzitola Music Studios in Holyoke. As the pit drummer for the city’s Valley Arena, Sefcik had played with nearly every major act coming through the Springfield area including The Dorsey Brothers, Lionel Hampton, Sammy Kaye and Count Basie; he was also a highly respected teacher who believed that stick control and rote memorization of rudiments were essential to a drummer’s success.

GEORGE LAWRENCE STONE

While studying under Sefcik for roughly 18 months, Morello became an extremely versatile player. He sat in with any group that would let him, played with combos at various events and joined a marching band in which his ability to apply a broad range of rudiments with razor-sharp precision expanded exponentially.

His skills had developed so profoundly by age 16 that Sefcik recommended he start taking lessons in Boston with the world-renowned George Lawrence Stone, a New England Conservatory graduate who’d played with the Boston Festival Orchestra and the Boston Opera Orchestra. He’s also been the pit drummer at Boston’s Colonial Theatre, had trained the BSO’s Vic Firth and, in 1935, authored the seminal text Stick Control for the Snare Drummer, a staple among drummers to this today.

“Every lesson was a joy,” Morello said in 2006. “If you did something wrong, he had a way of letting you know about it, but without belittling you.” The respect was mutual, and Stone was so impressed with Morello’s addition of various accents to the exercises in Stick Control that he included some of them in his next textbook, Accents and Rebounds – also a staple among drummers to this day – and dedicated it to Morello, his star pupil.

SWITCH FROM CLASSICAL TO JAZZ, RUDIMENTS CHAMPION

Perhaps the most valuable lesson Stone gave Morello, beyond teaching him how to read music and ways to best develop his technique, was that the future was in jazz, not in what Morello called “legitimate percussion” (meaning in classical orchestras). Taking that input to heart, during his nearly three years of training under Stone, Morello broadened his perspective and became the New England champion of the National Association of Rudimental Drummers competition while jamming regularly with his jazz-focused friends from the Springfield area. Several of those friends became top-tier sidemen including saxophonist-clarinetist Phil Woods (Dizzy Gillespie, Benny Goodman), pianist-vibraphonist Teddy Charles (Charles Mingus, Miles Davis), guitarist Sal Salvador (Stan Kenton) and double-bassist Chuck Andrus (Woody Herman).

FIRST TOUR, MOVE TO NEW YORK CITY, THE DAVE BRUBECK QUARTET

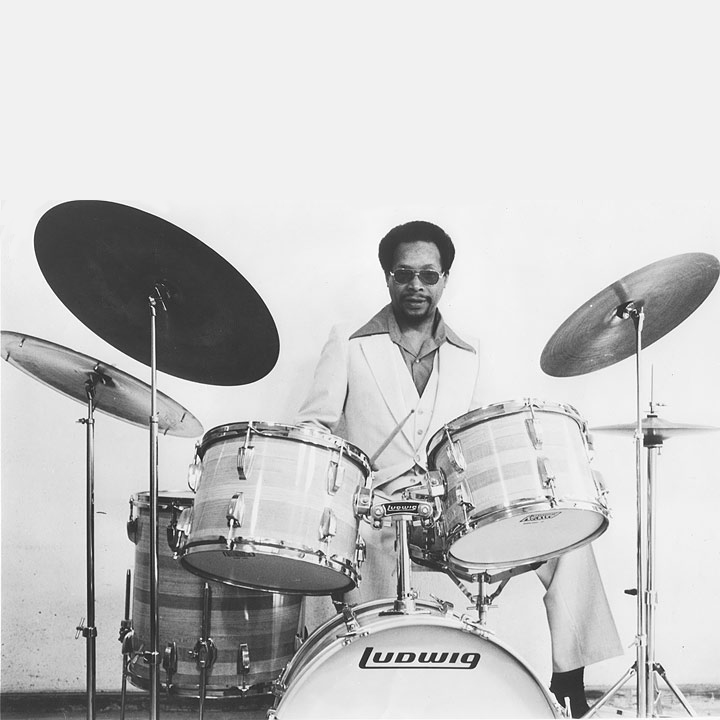

In 1950/1, Morello’s first gigs outside New England were touring with country-jazz guitarist-songwriter Hank Garland and Whitey Bernard and His Orchestra. Widely known as the best drummer in western Massachusetts, he moved to New York City in 1952 and soon found work with an impressive list of serious jazz cats including guitarists Johnny Smith and Tal Farlow, saxophonist Gil Mellé and two friends from around Springfield, Woods and Salvador, who’d also relocated to the Big Apple.

In 1955, Morello got the break that brought him international renown when Paul Desmond, saxophonist in The Dave Brubeck Quartet (TDBQ), saw him playing a gig with pianist-composer Marian McPartland’s trio and admired his understated use of brushes. After asking Brubeck – who formed TDBQ in 1951 with Desmond and used different bassists and drummers during their first four years – Desmond invited Morello to join TDBQ on a summer tour that included debuting at Music Inn in Lenox and the Newport Jazz Festival.

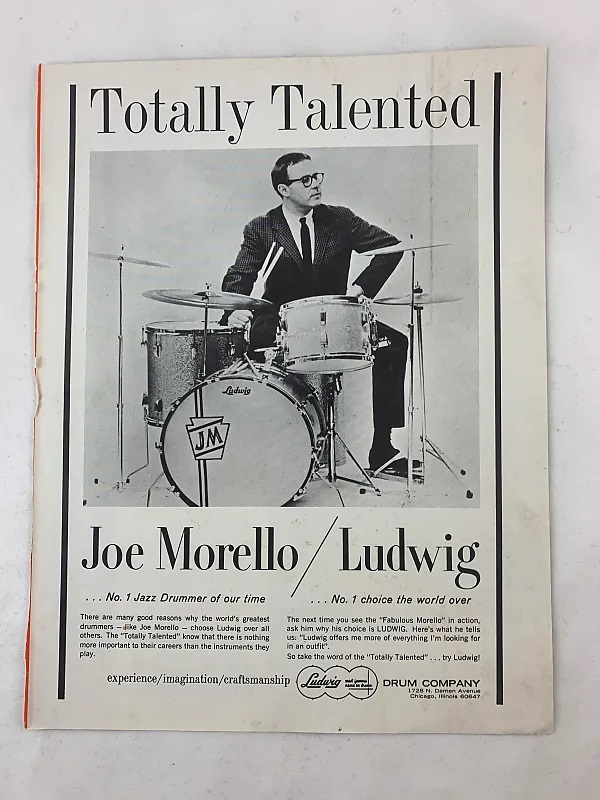

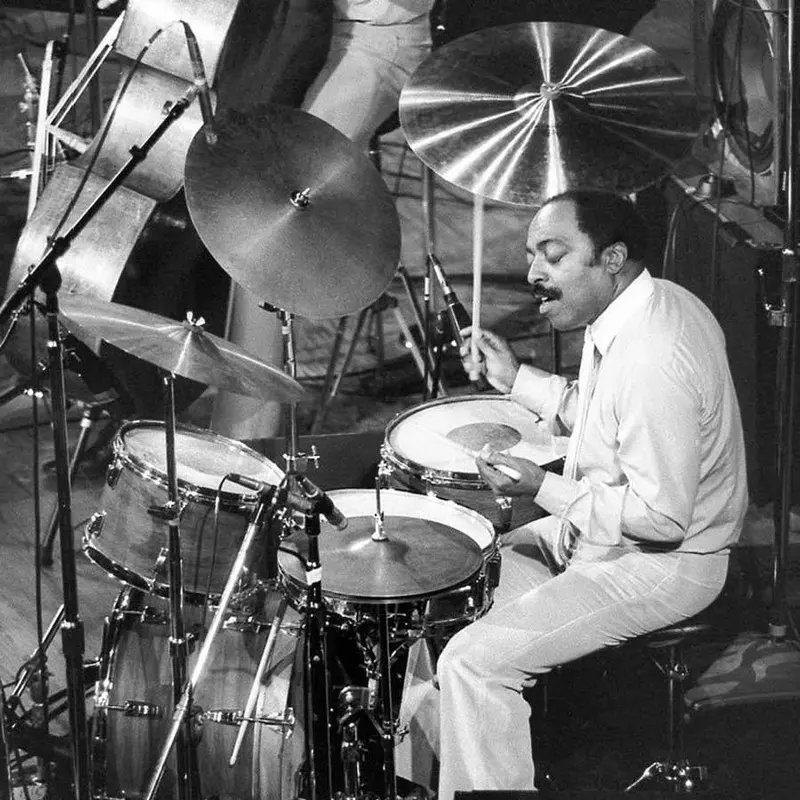

In 1956, after turning down offers from bandleaders Benny Goodman and Tommy Dorsey, Morello joined TDBQ full time along with bassist Eugene Wright. The “classic” lineup of Brubeck-Desmond-Wright-Morello stayed together through 1967, recording two of their best-known tracks, “Take Five” and “Blue Rondo à la Turk,” both of which showcase Morello’s blend of a classical player’s unwavering accuracy, a free-jazz musician’s improvisational instincts and his comfort with odd time signatures. With an outward calm that concealed the amazing ambidexterity and complexity of the polyrhythms he produced, Morello injected a new “cool” into TDBQ’s jazz – effortlessly, it seemed, “as if he were chopping vegetables,” said one critic.

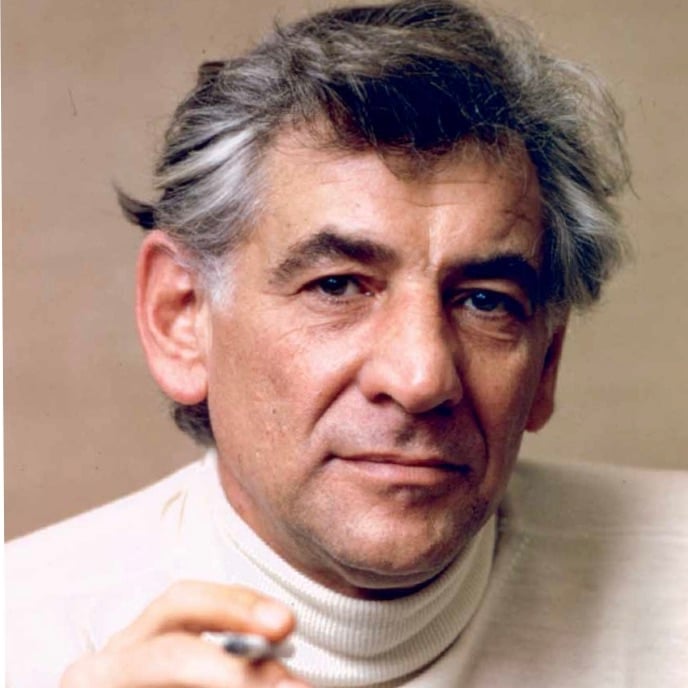

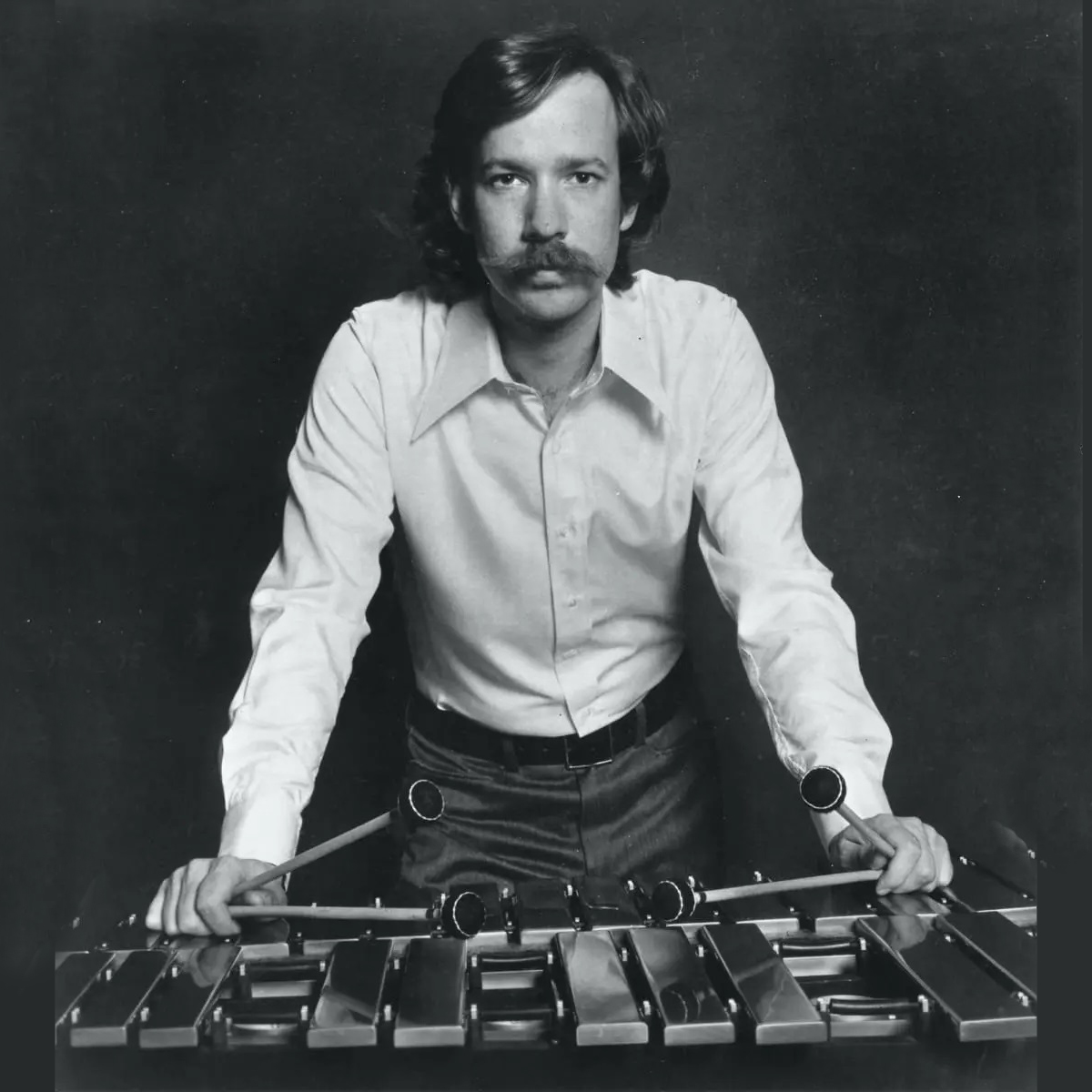

He appears on 36 TDBQ albums, including 1959’s platinum-selling Time Out, which reached #2 in the Billboard Pop chart and 1961’s Bernstein Plays Brubeck Plays Bernstein, a collaboration with composer and Lawrence, Massachusetts, native Leonard Bernstein. During his time with TDBQ, Morello also played on LPs from several other artists including virtuoso vibraphonist Gary Burton and guitar great Howard Roberts.

POST-BRUBECK ACTIVITY, DEATH, LEGACY

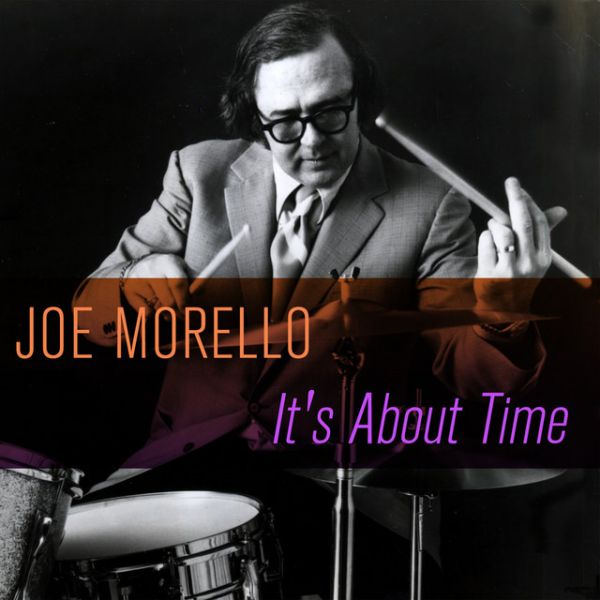

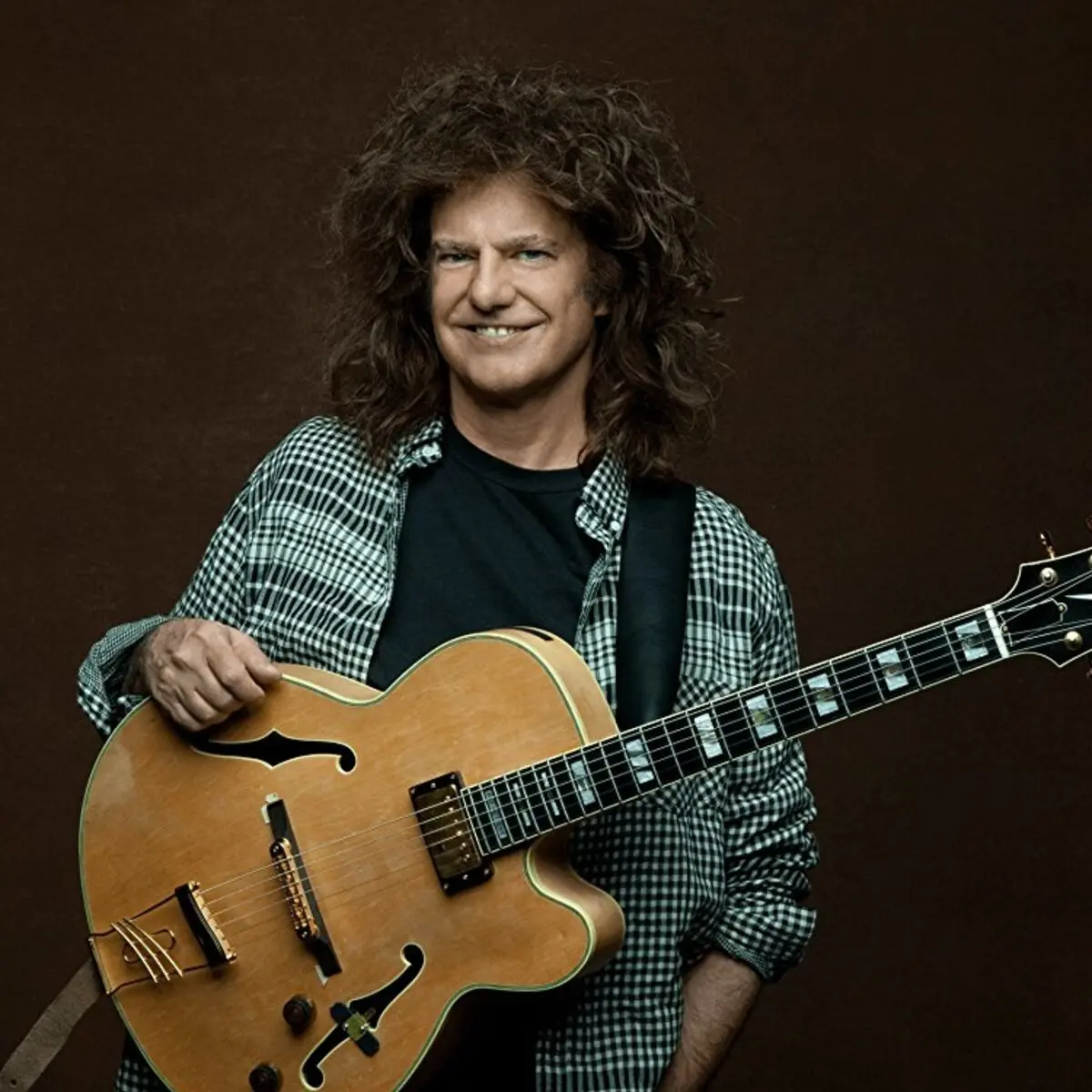

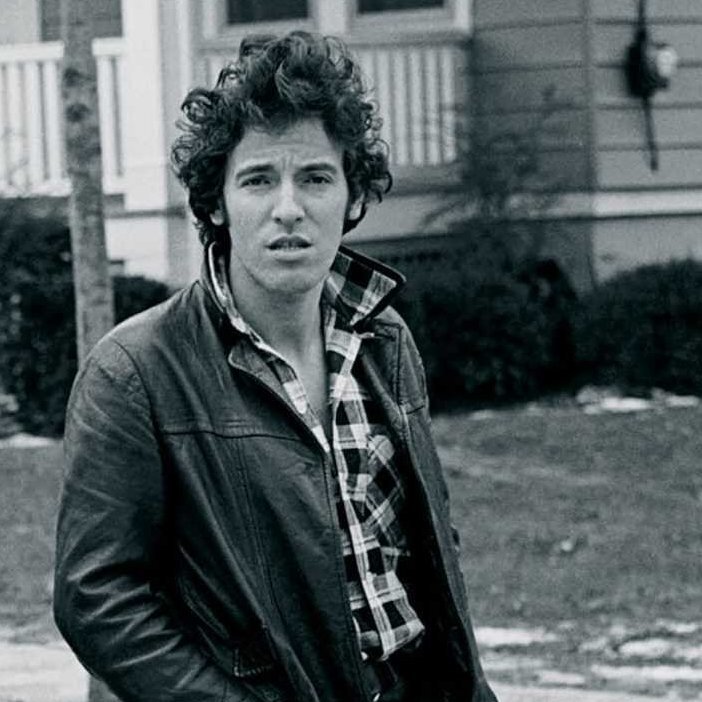

When TDBQ disbanded in 1967, 39-year old Morello began hosting drum clinics and teaching; among his more high-profile students were Bruce Springsteen‘s longtime drummer Max Weinberg and The Pat Metheny Group’s Danny Gottlieb. He played with Brubeck occasionally – including on TDBQ’s 1976 live album 25th Anniversary Reunion – and gigged around New York with his own quartet while recording three albums as bandleader and appearing on LPs by Art Pepper and Tony Bennett. He wrote several texts on rudiments, soloing and playing in uneven time signatures.

On March 12, 2011, Morello died at age 82. In a statement released immediately upon hearing the news, Dave Brubeck wrote in part that “his drum solo on ‘Take Five’ is still being heard around the world.” And surely Morello’s work will resonate across countless more decades and influence untold numbers of drummers, a fact the famously reserved New Englander would find both flattering and surprising.

(by D.S. Monahan)