The Beacon Street Union

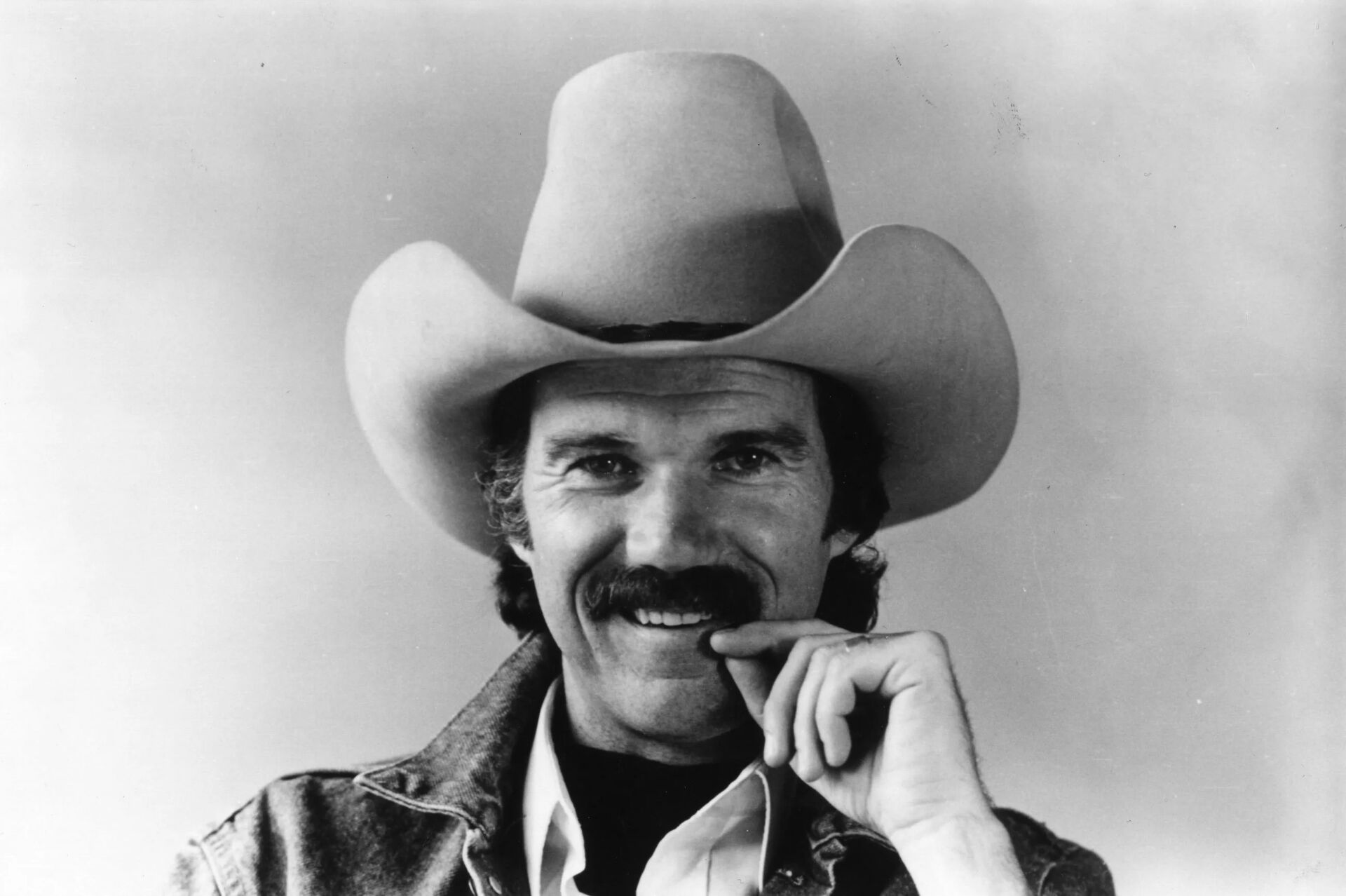

In just 18 months, The Beacon Street Union went from being one of Boston’s top local bands to achieving national recognition. Keyboardist Bob (Rhodes) Rosenblatt formed the band in the summer of 1966, recruiting two fellow Boston College students, bassist Wayne Ulaky and vocalist John Lincoln Wright, a high school acquaintance, guitarist Paul Tartachny, and a childhood chum, drummer Dick Weisberg.

The quintet cut its teeth by playing covers of American blues classics, just like thousands of other groups during the British Invasion era. Influenced in a big way at first by The Yardbirds’ 1967 album Little Games and its exploration of psychedelic flourishes, the band’s sound was as raw as it was driving. Local rock heroes The Remains were also a major influence, as were Greenwich Village-based The Blues Project and the pulsating, hypnotic rhythms of The Velvet Underground.

EARLY GIGS, MGM SIGNING, “BOSSTOWN SOUND” INITIATIVE

The Beacon Street Union began by playing in local bars, but the bar owners had little patience for musical experimentation. They found more enthusiastic audiences on college campuses and in showcase venues developing out of the Boston/Cambridge coffeehouse scene, eventually finding a home at the newly opened Boston Tea Party, Boston’s first psychedelic ballroom, located in an abandoned synagogue on East Berkeley Street.

In June of 1967, the band headed to New York City to see if they could score some gigs, eventually landing a few at The Bitter End, Café Wha and Steve Paul’s The Scene. During a five-week summer residency at the latter, they met independent producer Wes Farrell, who took a strong interest in the band; they soon they found themselves in the studio laying down some original material. Farrell made a distribution deal with MGM Records and – unbeknownst to the anybody in the actual band – the label packaged The Beacon Street Union with two other Boston bands, Orpheus and Ultimate Spinach, both produced by independent producer Alan Lorber, originator of the short-lived Bosstown Sound initiative.

THE EYES OF THE BEACON STREET UNION

Now a unwitting part of MGM’s Bosstown Sound promotion campaign, the group enjoyed nationwide publicity on the release of their first LP, The Eyes of the Beacon Street Union, in January 1968. Sales were impressive, supported by a string of live dates across North America and several TV appearances, and a number of mainstream publications ran favorable reviews and profiles of the band.

In late January, just two weeks after the debut LP’s release, Newsweek magazine ran a Lorber-penned piece about the Bosstown Sound. The associated ad campaign began to attract attention in the underground press, too, drawing accusations that the notion that there was in fact a particular “Boston” sound was a crass marketing ploy by MGM. In May, the album peaked at #75 in the Billboard 200 as sales started to fall away, the early impetus having stalled due to the “Bosstown Sound” backlash.

”BLUE SUEDE SHOES,” THE CLOWN DIED IN MARVIN GARDENS

In April 1968, MGM releases the second Beacon Street Union single, their cover version of Carl Perkins’ “Blue Suede Shoes,” delivered in true rock ‘n’ roll style. Stripped of Wes Farrell’s studio tricks, the track provided a glimpse of what the Eyes of the Beacon Street Union album could have sounded like if the band had been allowed to keep to their original raw sound.

By June 1968, the band was back in New York, getting ready to go into The Record Plant in Manhattan to begin work with engineer Eddie Kramer on their second album, The Clown Died in Marvin Gardens, released in August. The contract that The Beacon Street Union had signed required that the band record new material on a scheduled basis so – having barely paused to take a breath since the release of their debut – they found themselves forced to return to the studio before they felt ready.

Farrell was enamored with the idea of producing a concept album centered around two new songs that the band had been trying out on their recent tour; “The Clown Died in Marvin Gardens” and “Angus of Aberdeen.” In concert, the band played “Clown” and “Angus” without a break, but on the album they were split by an orchestral piece titled “The Clown’s Overture” that Farrell invented.

Despite having written some new material, there wasn’t enough to fill an album, so the idea of creating a concept album was abandoned. As a result, they found themselves having to write new songs quickly and record them as the sessions progressed. To making matters worse, Farrell began introducing material from outside the group.

To augment these new tracks, some recordings from earlier sessions were used to fill out the album, most notably a 16-plus-minute treatment of Them’s “Baby Please Don’t Go” that progresses from straight R&B to laid-back jazz noodling via West Coast psychedelia and garage rock. It is probably the one track that comes closest to capturing the raw energy of the band’s best live performances.

LINEUP CHANGE, BECOMING “EAGLE”

In late 1969, the group returned to the studio for sessions on their third album, but this time they were determined to return to their roots as a live rock band, so the new material was more stripped down. That wasn’t the only change, though; in the spring of 1969, Bob “Rhodes” Rosenblatt returned to college full time and study law. Paul Tartachny left part way through the recording sessions, a move that saw Wayne Ulaky switch to lead guitar, and a new bass player joined, Englishman Bobby Hastings.

With the new line-up came a more straight-ahead rock sound – devoid of the studio effects and orchestrations that Farrell had featured so prominently on first two albums – and an identity change to distance themselves from the Bosstown Sound concept. The Beacon Street Union became Eagle.

COME UNDER NANCY’S TENT, DISBANDING

The result of the sessions was Come Under Nancy’s Tent, which MGM released in March 1970 and included the Wright/Rhodes/Ulaky composition “Kickin’ It Back.” On August 12, 1970, Eagle opened for Janis Joplin at Harvard Stadium, which was her last public performance before her death, and they disbanding shortly afterward.

The original five members of The Beacon Street Union had a chemistry that wasn’t always harmonious, but it was intense, and it was real. They fought and argued, and sometimes alienated each other, but they were passionately dedicated to their mission: rock hard, rock the boat, and rock out – take no prisoners and don’t look back. They were young and they were cocky. They had a dream – and it almost came true.