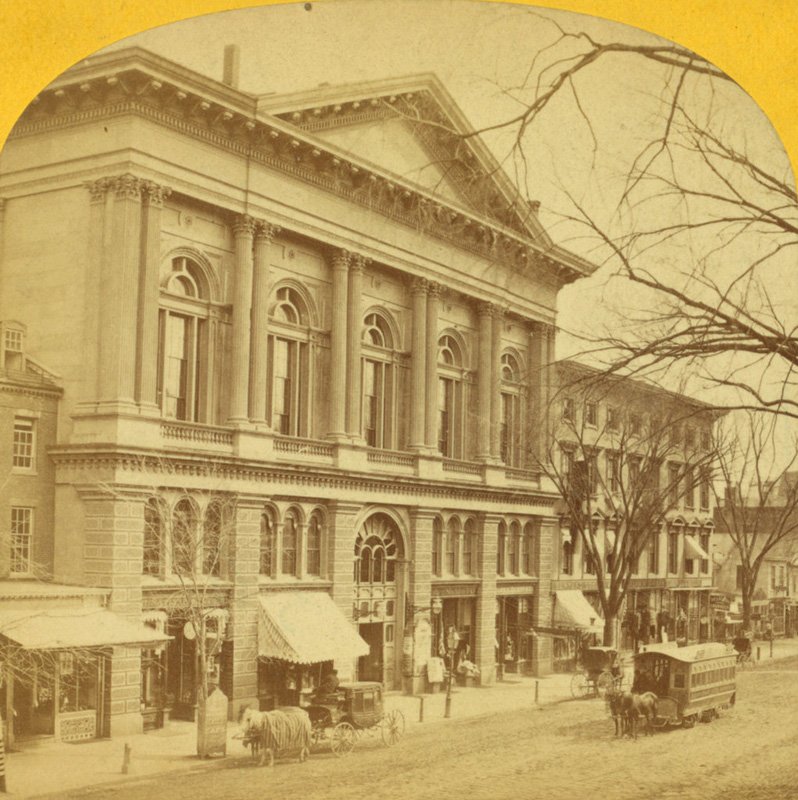

Mechanics Hall

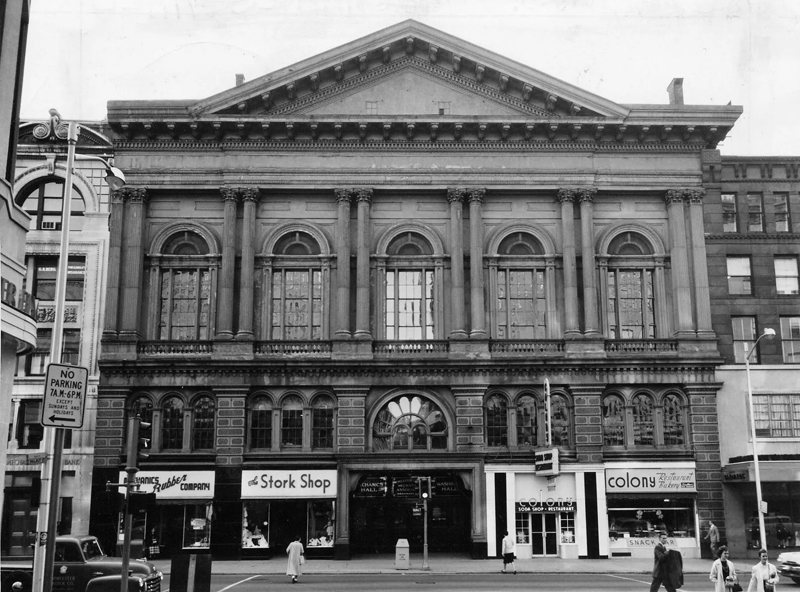

Opened in 1857, Mechanics Hall is the most historic music venue in Worcester, Massachusetts, but it’s significance stretches far beyond the city limits. In fact, it’s one of the most culturally important structures in the United States, as the National Register of Historic Places recognized in 1972 when it added the Hall to its prestigious list. And as anyone who’s familiar with its history, façade and interior knows, the venue was a supremely worthy addition since it ticks every box in the NRHP’s inclusion criteria.

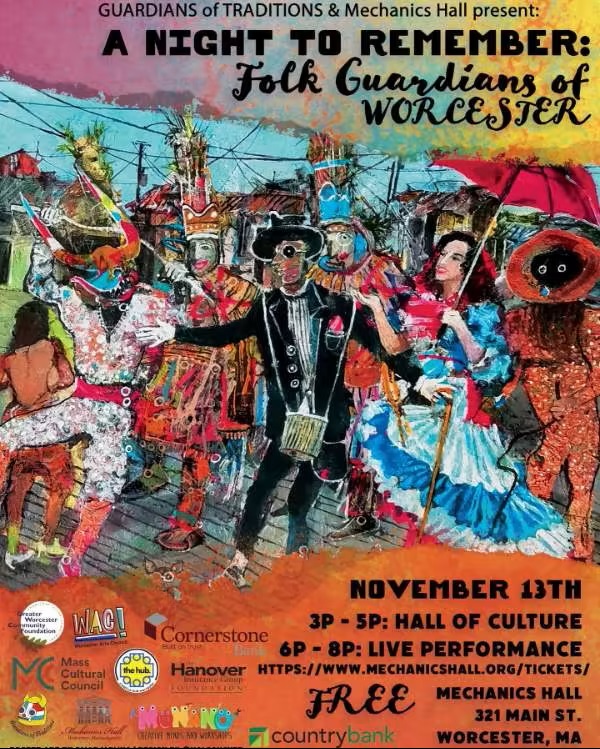

The Hall has been referred to as New England’s “most spacious and beautiful hall,” is widely considered by architectural historians to be the finest example of pre-Civil War concert halls in the US, boasts sublime acoustics and is home to the oldest unaltered four-keyboard pipe organ in the Western Hemisphere. While it’s experienced a number of ups and downs in terms of popularity and use over the decades, it’s hosted a broad swath of live music during its nearly 170-year existence, from classical, opera, jazz and blues to folk, country, rock and rap, becoming a microcosm of the public’s ever-changing tastes.

BACKGROUND, WORCESTER COUNTY MECHANICS ASSOCIATION

The Hall’s story begins in the early 1800s with the opening of the Blackstone Canal that linked Worcester and Providence (in 1828) and the completion of the Boston & Worcester Railroad (in 1835); the canal and railway dramatically improved transportation of materials and manufactured goods to and from the city, turning it into an industrial powerhouse. Throngs of people moved to Worcester as a result, expanding its population from roughly 8,000 in 1840 to about 40,000 in 1870 and some 120,000 by 1900.

In November 1841, realizing that the burgeoning industrial workforce needed to develop new skills in order to remain competitive and learn how to manage the massive economic and social changes impacting their lives, a group of local men led by inventor and wire manufacturer Ichabod Washburn established the Worcester County Mechanics Association. The organization provided members with the latest books on topics like mechanical drawing, blueprint reading and pipefitting and offered classes on such subjects; members could also take part in debates and attend lectures on social issues (particularly abolition, women’s rights and temperance), join discussions about economic and political theory and learn about social etiquette, making the training a balance of science and the arts.

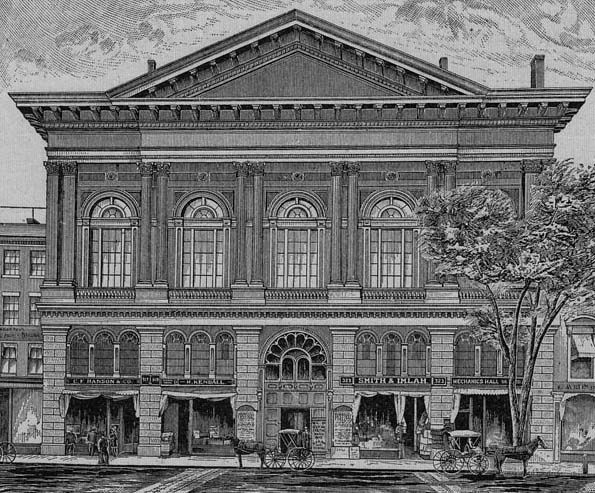

By early 1842, the Association had 115 members and by 1854 it had outgrown its rented space. Deciding to build its own facility at 321 Main Street, the group hired architect Elbridge Boyden, a Worcester-based Vermonter who’d designed Taunton State Hospital three years before. The groundbreaking ceremony was held in July 1855 and the cornerstone was laid in September that year, followed by a parade that included the Boston Brass Band, the Worcester Light Infantry and the City Guards.

OPENING, NOTABLE SPEAKERS, HOOK ORGAN

The Hall opened on March 19, 1857, drawing effusive praise from tradesman and artisans alike for its construction, mechanical systems, elegant interior and state-of-the-art acoustics and establishing the Worcester area’s workforce as leaders in the burgeoning Industrial Revolution. The first graffiti was scrawled inside one of its two ticket booths soon after the opening and various names and phrases have been etched into the wood and the stained glass of both since then.

Mechanics Hall includes two actual halls, the 1,300-seat Great Hall and the 300-seat Washburn Hall, in addition to meeting rooms and a library, which made it the largest public venue by far in Central Massachusetts during the second half of the 19th century. The combination of its size and acoustics – which allowed audiences to hear those on the stage with near-perfect clarity in the decades before amplification – attracted prominent figures including Charles Dickens who, in March 1868, read his story “A Christmas Carol” and part of his novel “The Pickwick Papers” aloud for the audience. Others speakers have included Mark Twain, Susan B. Antony and US presidents William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, William Taft, Woodrow Wilson, Gerald Ford and Bill Clinton.

In October 1864, the Association installed a four-keyboard pipe organ made by Boston-based E. and G. G. Hook, placed among floor-to ceiling Corinthian-style columns and flanked by portraits of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. According to the Hall’s website, Association leader Washurn spearheaded the effort to acquire the instrument – which cost $9,000 (about $342,000 in 2025) – by offering to pay $1,000 himself, stipulating that the Mozart, City Missionary and Children’s Friend Societies be able to use the Hall for free once a year for a concert. Other business leaders stepped up to raise the balance for the organ – officially called an E. & G. G. Hook (Opus 334, 1864) but widely known as a Hook Organ – and it’s now the oldest of its kind in the Western Hemisphere located at its original installation site.

PORTRAITS, EARLY CONCERTS, NEAR DEMOLITION, RENOVATION

In 1866, the Hall installed the first of its 24 portraits, each of a 19th-century figure who was a member of the Hall, a Civil War hero, a political leader or social reformer with close ties to Worcester (with the exception of Washington, whose portrait was the first one placed in the Hall, followed by Lincoln’s). The Hall didn’t include portraits of women until 1999 (when it added ones of Clara Barton, Dorothea Lynde Dix, Abby Kelly Foster and Lucy Stone) and it added the first portraits of Black Americans in 2024 (Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and William and Martha Ann Brown).

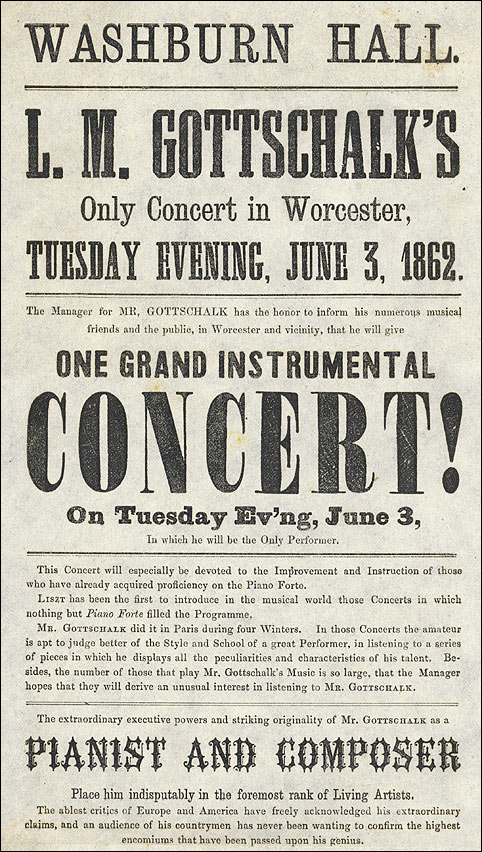

In the early 1870s, by which time Worcester had become a frequent stop for touring musicians, the Hall hosted some of the most internationally acclaimed talents of the era including pianist-composer-conductor Anton Rubinstein, violinist-composter Henryk Wieniawski and opera singers Nellie Melba and Jenny Lind. During the first 20 years of the 20th century, it presented opera singer Enrico Caruso, pianist Vladimir de Pachmann and composer-pianist-conductor Sergei Rachmaninoff, among others, and between 1918 and 1924 the New York Philharmonic made annual appearances at the Hall.

By the time World War II ended in 1945, however, the venue was struggling to stay afloat, having endured over 15 lean years due to the Great Depression’s devastation of the US economy and thousands of men being sent overseas during the war. To make matters worse, the return of GIs from Europe and the Asia-Pacific resulted in newer, more modern venues popping up in Worcester and the surrounding area. Without the money to draw top musical talent, the Hall hosted professional wrestling, dance classes, 4-H club meetings and a variety of other events to make ends meet before putting the space on the market in 1948 to no avail. The venue became a roller-skating rink in 1950 in an effort to turn its economic tide and was put up for sale for a second time in 1952, again to no avail.

The Hall held very few concerts in the ‘60s, though country singers Kitty Wells and Bill Phillips appeared, as did the popular country duo Johnny & Jack. By the early ‘70s, years of neglect and lack of regular use had left the space in serious disrepair and facing near-certain demolition. It was shuttered for several years starting in 1972, but when word got out that the Association was thinking of tearing it down, Worcester residents rallied to raise about $5 million (about $26.3 million in 2025) to restore the Hall to its 19th-century splendor, allowing it to reopen in 1977. “The people of Worcester saved this place,” said Kathlene Gagne, the Hall’s executive director, in a 2024 interview with Sarah Barnacle of The Worcester Telegram & Gazette. “It’s truly amazing.”

NOTABLE ‘70S/’80S/’90S/’00S APPEARANCES, COVID RECORDING SESSIONS

From late 1978 until the end of the 1980s, the Hall hosted a number of major artists, despite the fact that it wasn’t in a financial position to compete head-to-head for new acts with more popular Worcester venues such as E.M. Loew’s Theatre of Performing Arts (now The Palladium) and the Centrum (now DCU Center). Among those who appeared were Ella Fitzgerald, Ray Charles, Tony Bennett, Mel Tormé, Tommy Makem, Roger McGuinn, The Clancy Brothers & Robbie O’ Connell and Gene Clark. Since 1983, the Hall’s held free, one-hour concerts in the spring and fall as part of its Brown Bag Concert Series; people are encouraged to bring their lunch to the shows, which take place at noon on weekdays and usually feature chamber music and smooth jazz.

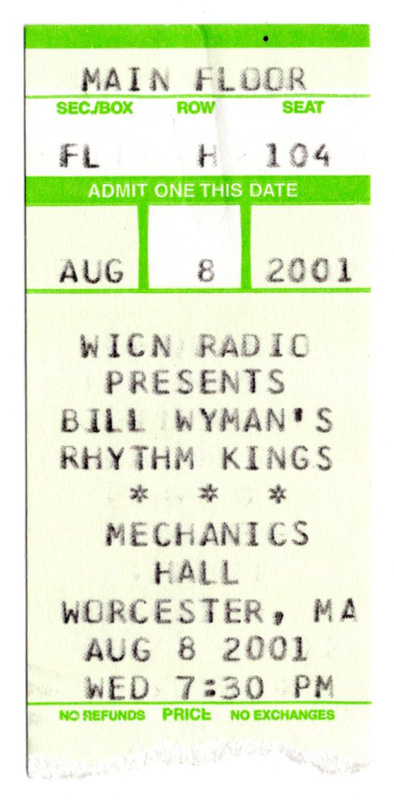

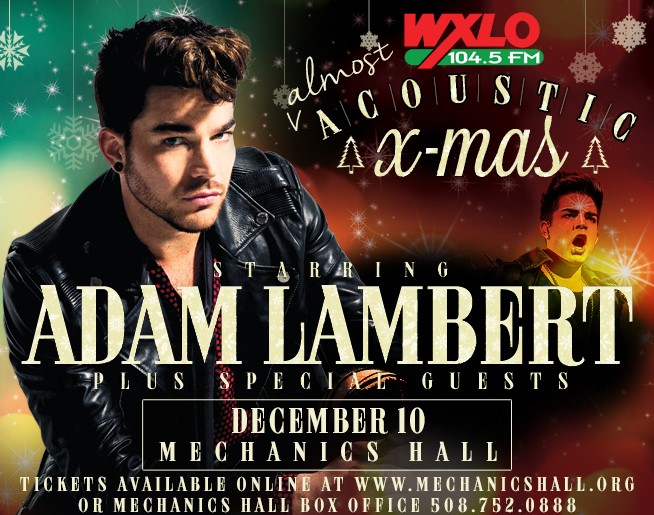

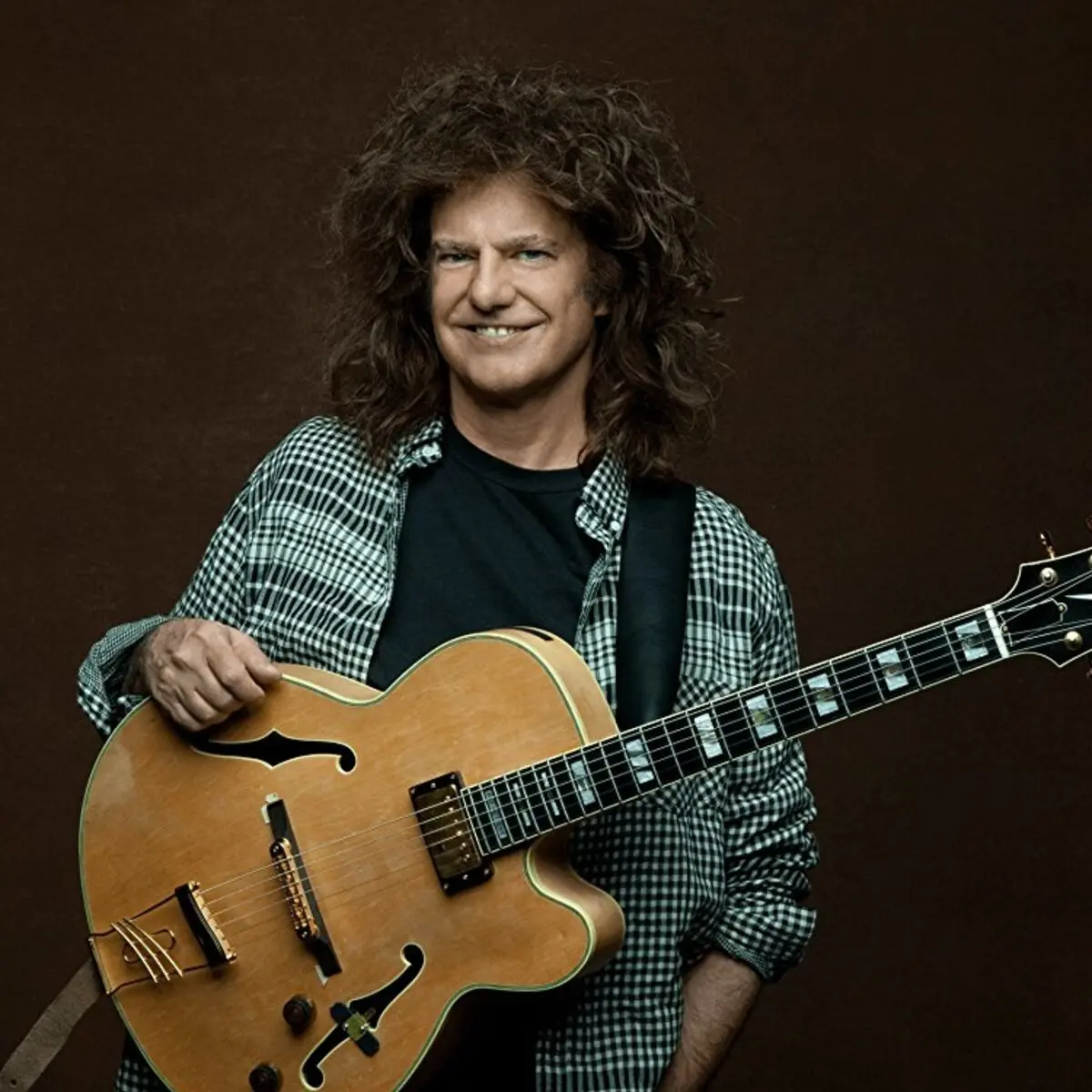

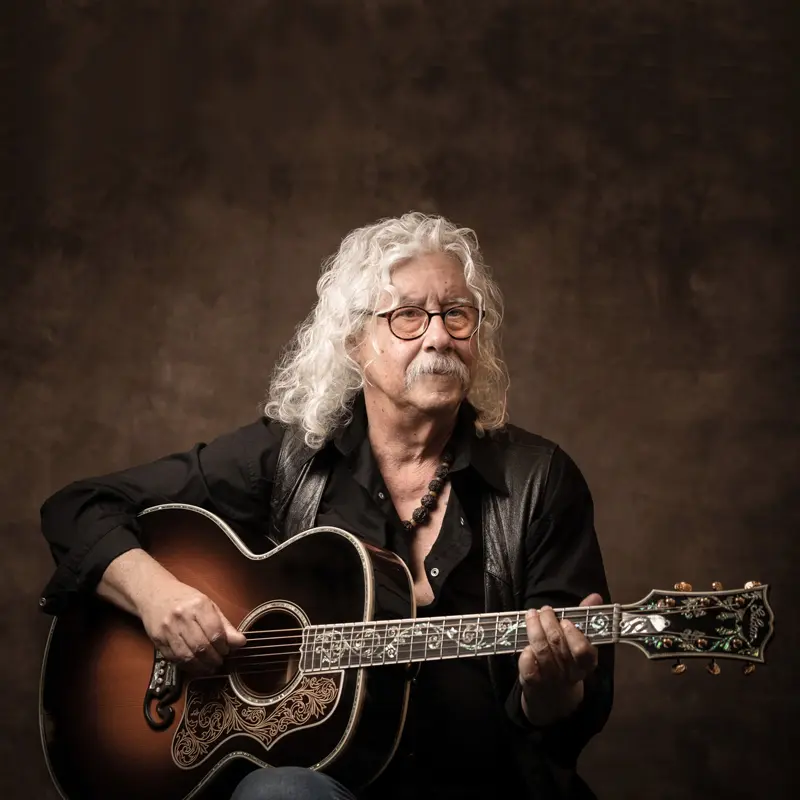

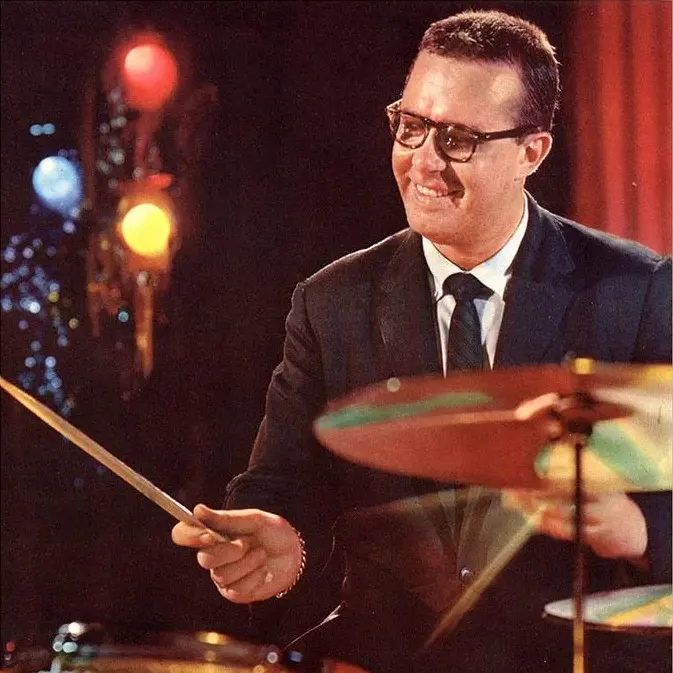

The Hall was able to land some future stars in the ‘90s including Ani DiFranco and Emmylou Harris and a few household names such as Gordon Lightfoot, but it didn’t become the modern music mecca that it is today until the 2000s. The first decade of the new century represented a dramatic comeback for the venue, with appearances by a laundry list of celebrated artists from across the musical spectrum, including New England-rooted ones Guster, Pat Metheny, Dar Williams and Arlo Guthrie. Among the others who took the stage were Sonny Rollins, Linda Ronstadt, Vince Gill, Crosby, Stills & Nash, Ellis Marsalis, Bill Wyman’s Rhythm Kings, The Boys Choir of Harlem and The Dave Brubeck Quartet. In 2008, the Hall was a stop on the Monterey Jazz Festival’s 50th anniversary tour and in 2009 it was included on Blue Note Records’ 70th anniversary tour.

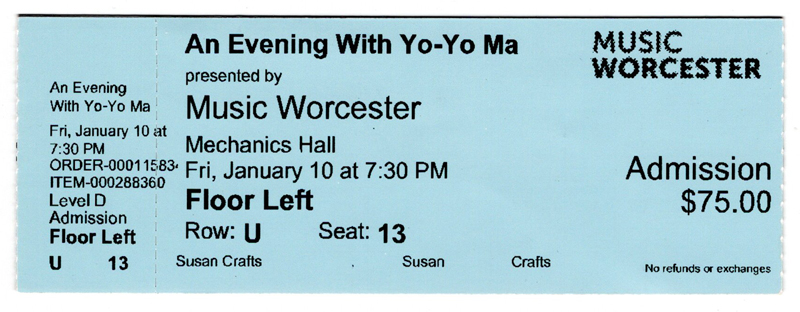

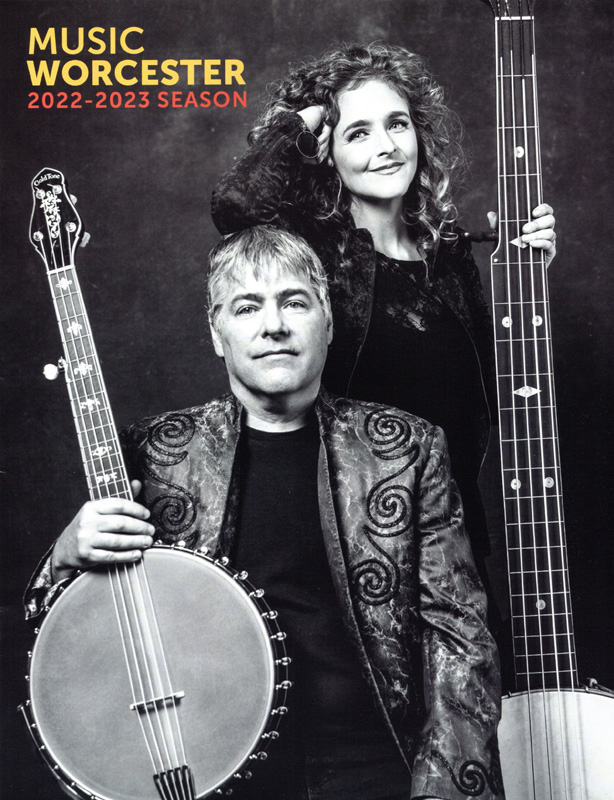

Over the past 15 years, New England-rooted artists Livingston Taylor, John Cafferty, Ellis Paul, Johnny A., Paul Rishell and Annie Raines and Billy Squier have performed at the Hall, as has Rhode Island-based Roomful of Blues. Others include Edgar Winter, Rick Derringer, Art Garfunkel, Wynton Marsalis, Branford Marsalis, John Sebastian, Béla Fleck, A Flock of Seagulls, John Hammond, Burton Cummings, The Sugar Hill Gang and Yo-Yo Ma.

During statewide Covid shutdowns in 2020 and 2021, the Hall held recording sessions in the space in order to stay in the black. “It was hard to get people together, but we were able to have about 50 recording sessions throughout the pandemic,” Gagne told Telegram & Gazette’s Barnacle, noting that local students applying to music colleges and conservatories often record in the Hall as part of the application process since its acoustics make it ideal for that purpose. “You wouldn’t believe the number of times I’ve heard someone say, ‘Oh, yes, I’ve played at Carnegie Hall, but I much prefer this place,'” she added.

(by D.S. Monahan)