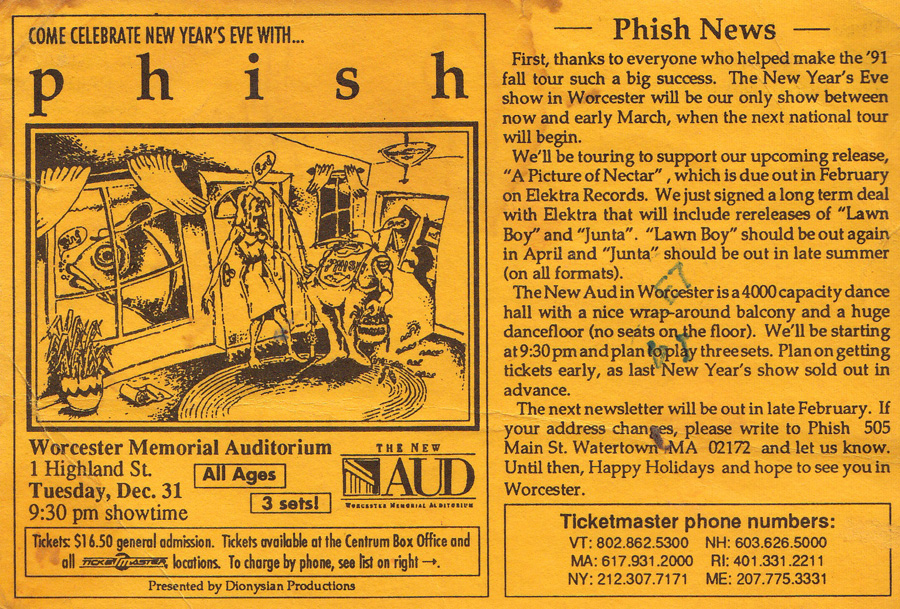

Worcester Memorial Auditorium

Since opening in September 1933, three months before Prohibition officially ended, Worcester Memorial Auditorium has towered over the city’s Lincoln Square, part of the Institutional District that includes the Worcester County Courthouse, the Worcester Art Museum, the Whispering Wall memorial, the former Worcester Historical Society building and the armory building. And though it’s been vacant since 2008, the inspiring structure was an enormous part of the local community for some 70 years as the location of election-day polling, civic meetings, fundraisers, graduations and various other events.

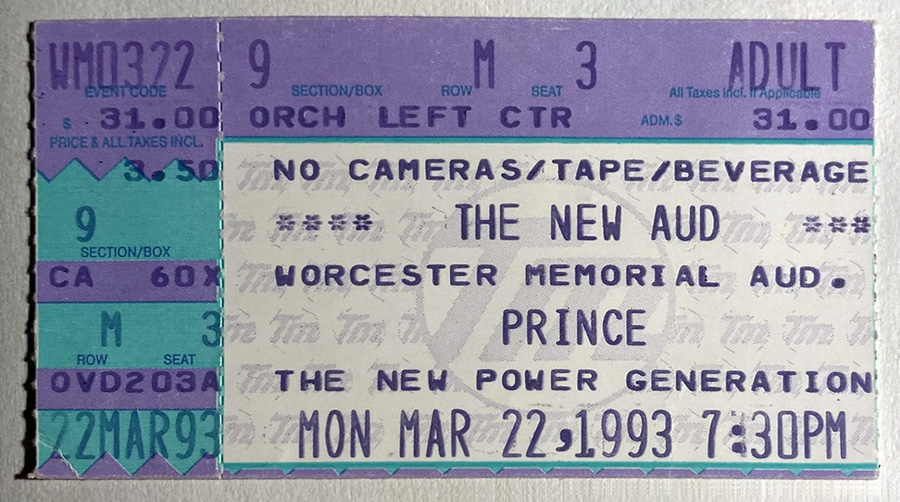

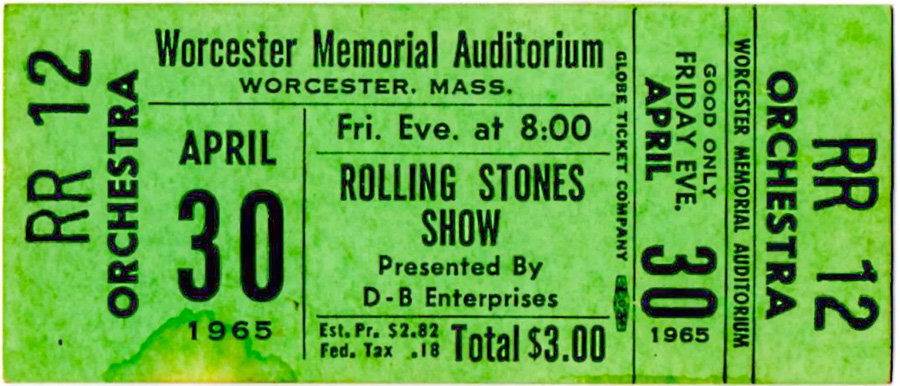

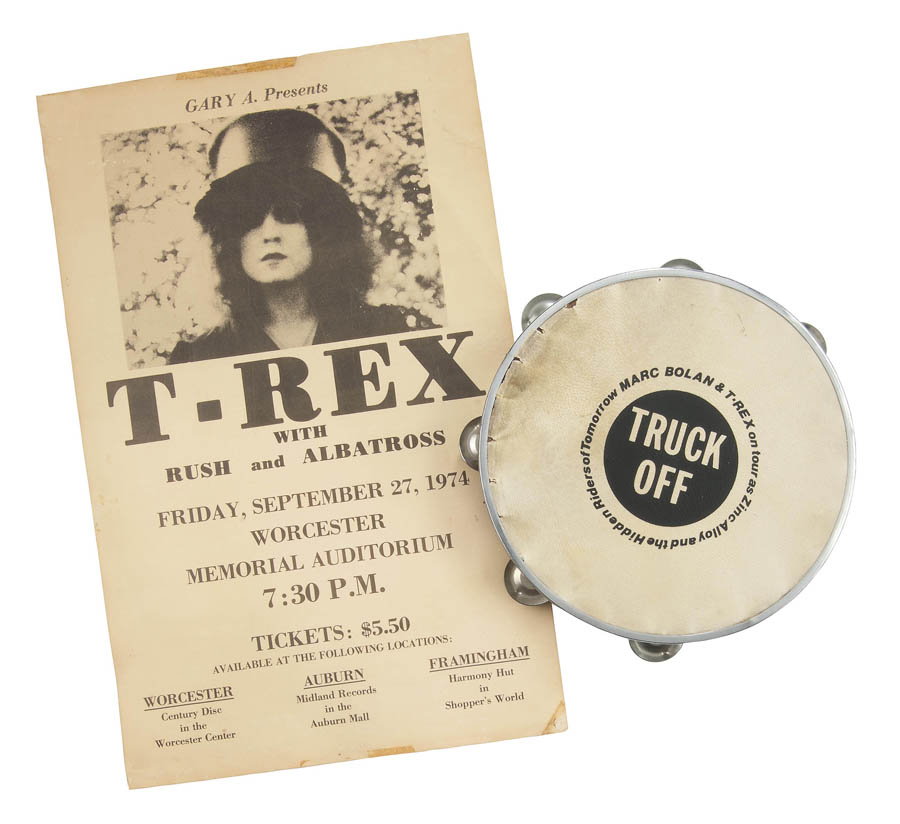

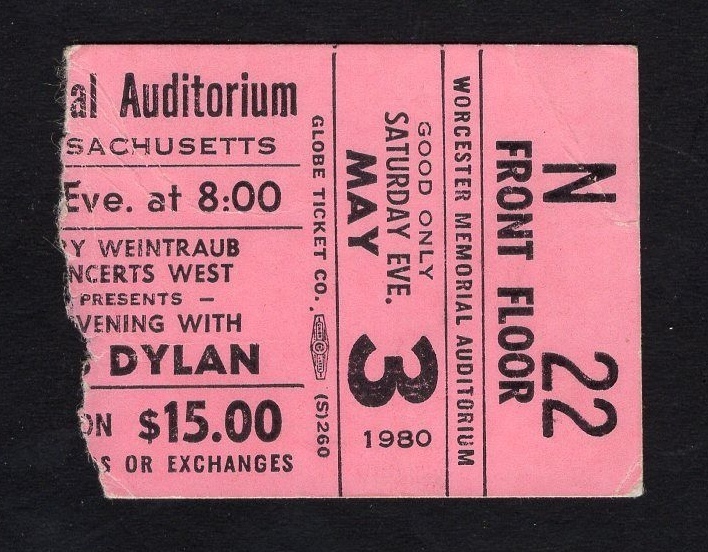

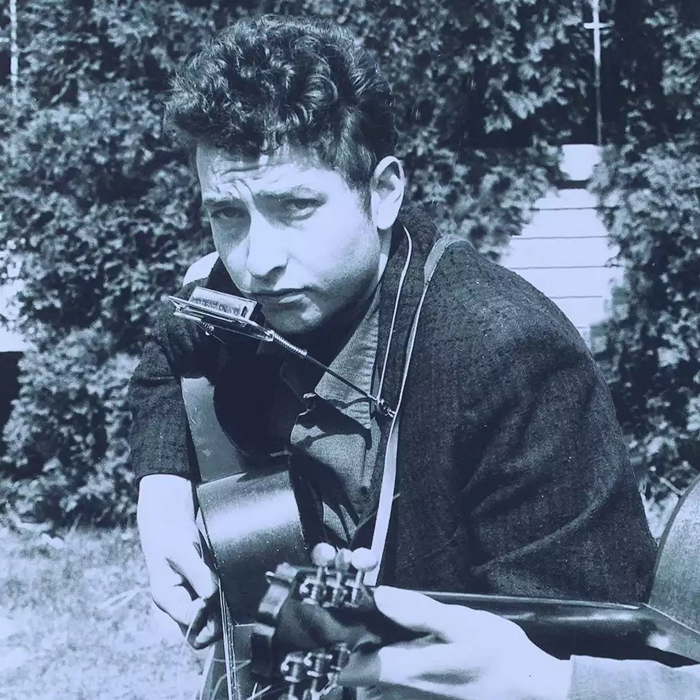

But for music lovers in the area, “the Aud,” as it’s known, is remembered as being a beacon of popular music from the early 1940s through the late ‘90s, during which time it presented a multigenred tour de force of nationally and internationally acclaim acts, reflecting changes in tastes between generations and becoming one of the region’s most beloved venues. From Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole and Gene Autry to Buddy Holly, The Rolling Stones, Simon & Garfunkel, Bob Dylan and Prince, the volume and variety of household names that took the Aud’s stage established it as a major part of the area’s panoramic musical landscape.

BACKGROUND, OPENING

The idea to construct what became Worcester Memorial Auditorium was discussed among local officials as early as 1917, when World War I was at its peak, with the full support of Mayor Pehr G. Holmes. In November 1918, days after the end of the war in which 9.000 Worcester residents fought and 355 died, Holmes assembled an Auditorium Committee that consisted of former mayors and other prominent members of the community, launching what became a decade-long search for a suitable site.

The initial proposal to construct the Aud on Worcester Common was rejected in 1925 and over the next several years the Committee searched for another location and the funds to make the project possible. In November 1929, they were able to purchase 100,000 square feet at Salisbury Street, Institute Road, Highland Street and Harvard Street thanks to the financial support of so-called “public-spirited citizens” and trustees of the Worcester Art Museum. Ironically, the Committee secured the funding just a few weeks after Black Thursday, Black Monday and Black Tuesday had ushered in the Great Depression.

The city held a nationwide search for architects before hiring Worcester-based L.W. Briggs Company, owned by Lucius Briggs, then the city’s most renowned architect, who collaborated on the project with New York City-based Frederic Charles Hirons, an MIT graduate. The groundbreaking was held in September 1931 and the cornerstone was laid on April 1932; inside it was a time capsule containing documents, city records, photographs, coins and a copy of Charles Nutt’s 1919 book History of Worcester and Its People. Construction finished in the summer of 1933 at a cost of $2 million (about $48.6 million in 2025) and the Aud was dedicated on September 26, followed by a week of concerts and other events and rave reviews for its cultural significance. “[The auditorium is] an enduring tribute to those whose sacrifice was sublime, a majestic memorial for the use and benefit of many generations,” according to a commentary The Worcester Telegram.

DESIGN, PIPE ORGAN, SHRINE OF THE IMMORTAL

Five stories high and constructed on a base of Deer Island granite, the Aud includes four separate spaces: the auditorium, a cavernous room with an official capacity of 3,509; The Little Theatre, which seats 675; the Memorial Chamber, which houses the Shrine of the Immortal; and the basement. The Little Theatre showed movies (using a film-projection booth accessed by a ladder) and hosted a variety of musical acts while the basement was used as office space. The auditorium includes a 6,853-pipe Kimball organ that’s never been altered and remains in working condition to this day.

The Shrine of the Immortal is the term for three murals that have been housed in Memorial Chamber since being formally presented in May 1941. Two depict Army and Navy soldiers in combat while the third, which was the largest mural in the US when it was unveiled, depicts a soldier ascending to Heaven. All were created over a period of three years by Leon Kroll, whose murals are also found in the US Department of Justice Building. Carved into Memorial Chamber’s walls are the names of the 355 Worcesterites who died in World War I – mostly soldiers, but also nurses – and three wrought-iron doors (symbolizing valor, victory and peace) lead to the auditorium balcony.

NOTABLE 1940S, ‘50S, ‘60S, ‘70S APPEARANCES

From the 1940s until the opening of Hart Recreation Center in 1975, the Aud was home court for the Holy Cross Crusaders basketball team and between 1946 and 2009 it was home to the Continental Basketball Association’s Bay State Bombardiers. Among the first musical events at the Aud were shows by Frank Sinatra in 1941, Duke Ellington & His Orchestra in 1943 and the New York Philharmonic in March 1947. The Aud presented jazz, pop and early rock acts in the ‘50s, including a concert in September ‘51 featuring Sarah Vaughan and The Nat King Cole Trio. Singing cowboy Gene Autry appeared in ’52 but, as rock commandeered the regional and national airwaves, most concerts for the rest of the decade featured acts playing the noisy new genre, including Chuck Berry and Fats Domino in ’56.

In a fascinating snapshot of the era, Worcester police were on edge before Domino’s show, according to the Aud’s archives, due to reports that his brand of rock often caused crowds to start dancing in the aisles; it turned out to be true, as reported in a review of the show in The Worcester Gazette. “One young man leaped into an aisle and gave a demonstration of Elvis Presley’s shivers that was surprising in its accuracy,” it read. “Another group in the rear of the hall, thwarted from dancing in the aisles, pushed rows of seats to one side so they could dance within the circle of seats formed, it. But the police eventually got in there too. When it was all over, the officers must have enjoyed their sighs of relief. One said he dreaded to think what might have happened if Fats played another 15 minutes.”

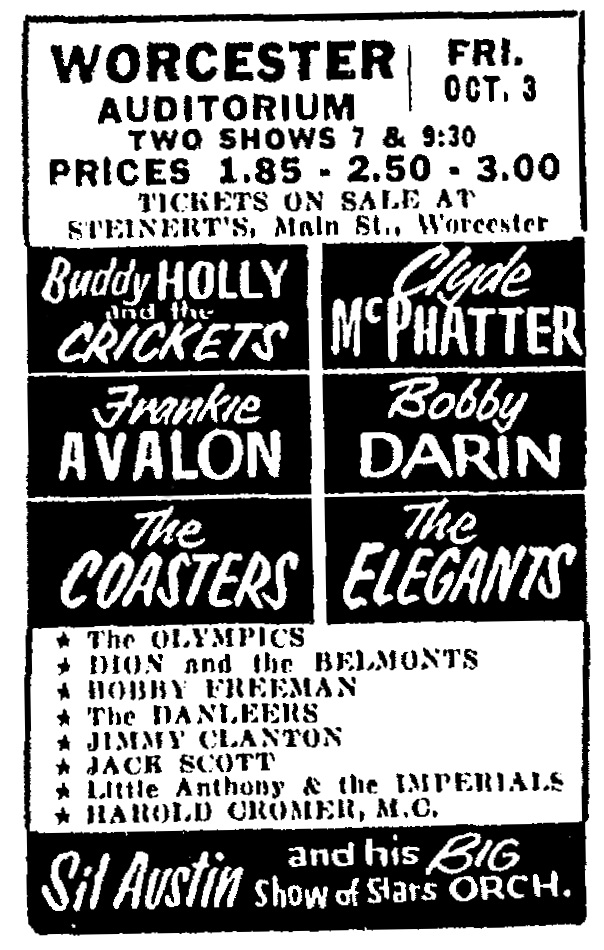

In October 1958, the “Biggest Show of the Stars,” headlined by Buddy Holly & The Crickets, made the Aud the first shop of their 17-city North American tour. Other acts included Frankie Avalon, Dion & The Belmonts, Bobby Darin, Duane Eddy, The Coasters and Little Anthony & The Imperials. The first part of the ‘60s saw appearances by Peter, Paul and Mary, The Charles River Valley Boys and Jim Kweskin & The Jug Band, and when The Beach Boys played at the Aud in October ’64, officials stopped the show after only a few songs. According to a December 2024 article by Michael Perna Jr. in Fifty Plus Advocate, a pack of screaming girls rushed the stage twice; after the first time, which caused the band to stop playing for several minutes, security guards warned them that the show would be stopped if they did it again. When they rushed the stage a second time just moments later, security pulled the plug on the show. “We didn’t even get a refund!” audience member Fred Anderson told Perna Jr.

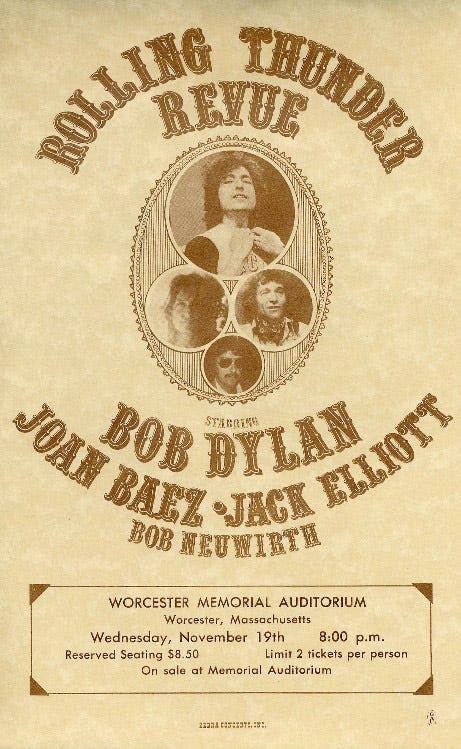

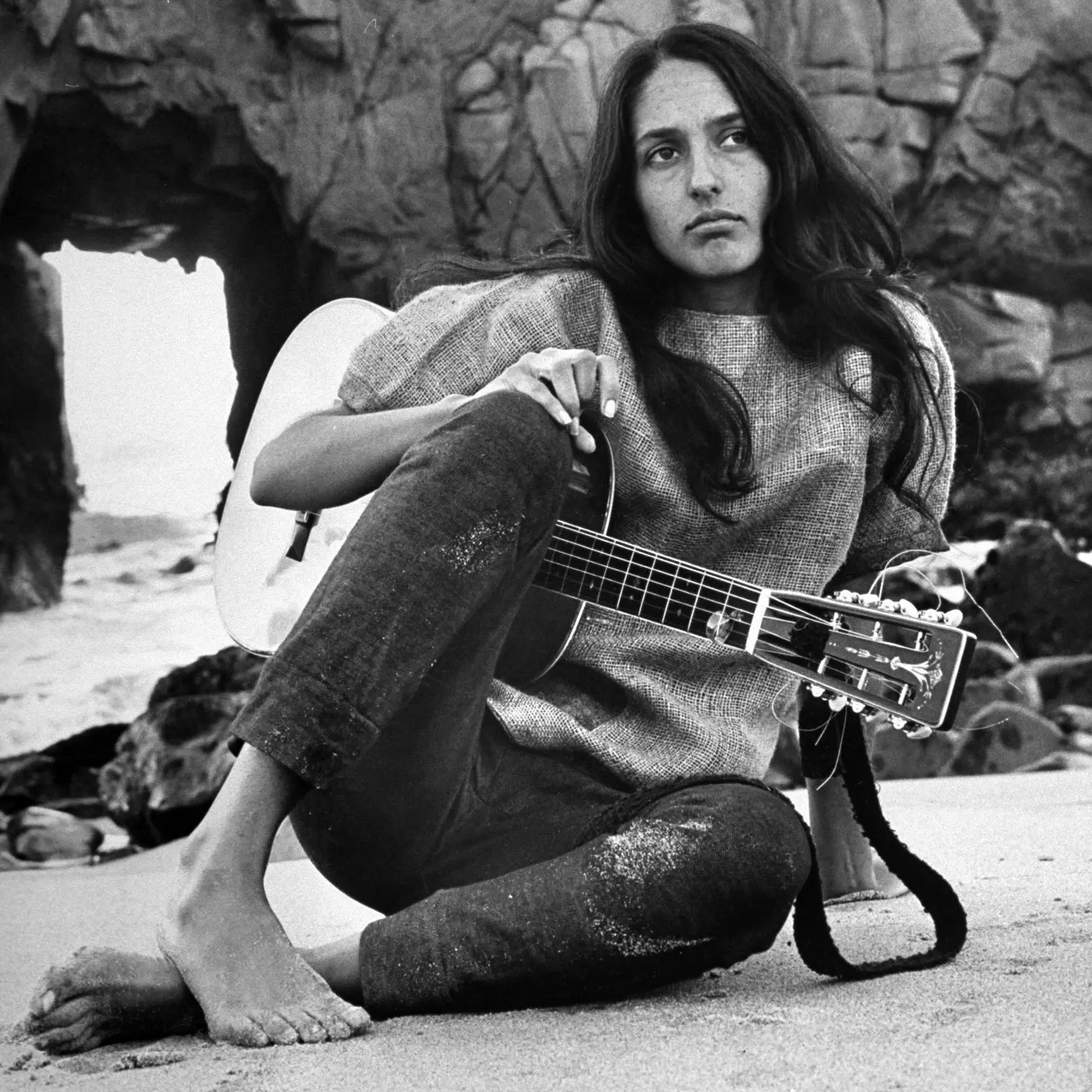

Other acts in the mid-‘60s included The Rolling Stones, who appeared on April 30, 1965, which was five weeks before the release of their chart-topping single “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.” It was the band’s first show in Massachusetts and second in New England, the first being at Loew’s State Theatre in Providence in November ‘64. “The music, what you could hear through the bedlam, wasn’t bad. Glenn Miller? No, but not bad,” wrote The Worcester Telegram ‘s Jack Tubert about the Aud gig. The Byrds, Harry Belafonte, Joan Baez and a wide variety of other major acts also appeared in ’65 and among those that performed at the Aud later in the ’60s were Simon & Garfunkel, Jethro Tull, The Beacon Street Union, Bob McCarthy, The Lost and Canned Heat. The ‘70s included shows by T. Rex, Harry Chapin, Rush, Judy Collins, The Grateful Dead and Bob Dylan, who took the stage in November ’75 as part of his Rolling Thunder Revue tour.

NOTABLE 1980S, ’90S APPEARANCES, DECLINE, CLOSING

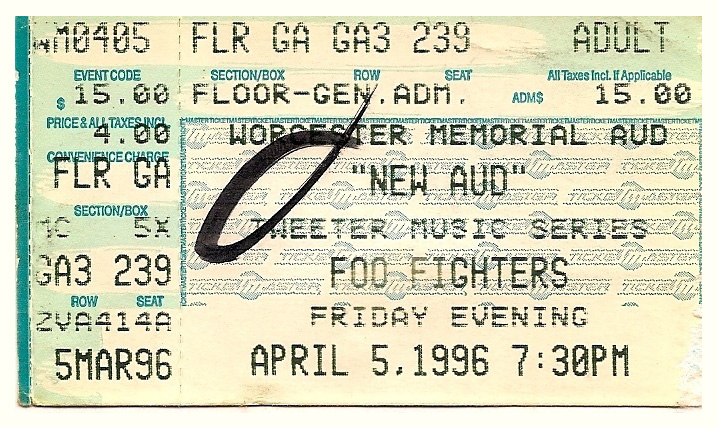

Dylan returned in 1980, the year the Aug was added to the National Register of Historic Places (as part of the Institutional District), and a broad assortment of other notable acts appeared during the rest of the decade including The Band, Chicago, B.B. King, Motörhead and Alice Cooper. The variety continued in the ‘90s with shows by The Allman Brothers Band, Tony Bennet, Ray Charles, Skid Row, Phish, Patti Smith, Ozzy Osbourne, The Mighty Mighty Bosstones, Foo Fighters and Prince, among others.

By the beginning of the 21st century, the construction of several new modern athletics and performance venues in Worcester had resulted in the Aud losing its place as the cultural/entertainment center it had been for the better part of seven decades. The building was used for different purposes for several years, including the basement as a juvenile court and the auditorium as a records-storage space, but fell into serious disrepair and has been vacant since 2008 except for occasional organ performances (until 2016) and SWAT training exercises.

ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE FOUNDATION, REVITALIZATION EFFORT

In 2016, the City of Worcester hired the Boston-based nonprofit Architectural Heritage Foundation (AHF) to conduct a feasibility study of the Aud and in May 2019 the city authorized the sale of the Aud to the AHF. Initial plans were to preserve the exterior facades, the Shrine of the Immortal murals, the Kimball pipe organ and the lobby while converting the auditorium into a modern space for competitive gaming and performances, the Little Theatre into an IMAX-style venue and the Memorial Hall into a restaurant.

“It’s a big space, with an even bigger chance to save a piece of history,” AHF project director Jake Sander told Meghan Parsons of Spectrum News 1 in 2023, noting that renovation would cost approximately $100 million. “The thought and investment that went into this building is really quite something. That’s why we believe in bringing it back. We know it’s going to take some time, but we think we can tell a story that will help preserve it.” The revitalization effort gained significant momentum in May 2025, when Massachusetts Governor Maura Healy announced that her administration would make a $25 million match commitment to help restore the historic structure, calling it “a vital cornerstone of Worcester’s civic and cultural identity.”

(by D.S. Monahan)