The Charles River Valley Boys

Anyone who assumes that bluegrass doesn’t germinate north of the Mason-Dixon line – let alone in the halls of Harvard, Yale and MIT – will see how wrong they are after one quick listen to The Charles River Valley Boys. Simply put, the band produced some of the knee-slappin’est, heel-clickin’est and just plain finest tunes ever recorded in stereo in the genre.

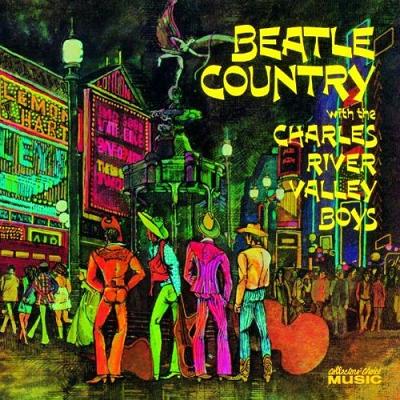

One of the first urban bands to play bluegrass as anything but a gimmick, TCRVB helped to spark and sustain the folk revival in Cambridge and the greater US through most of the 1960s. While their original songs were rooted those in written by bona fide old-time legends – particularly Tennessee native “Uncle Dave” Macon, North Carolina Ramblers’ frontman Charlie Poole and Georgia-born fiddler Gid Tanner – their pioneering final album, Beatle Country, is one of the earliest examples of the Fab Four’s catalogue being reworked into something entirely new and has been praised as an example of sheer artistic brilliance.

Formation, Lineup, Early performances

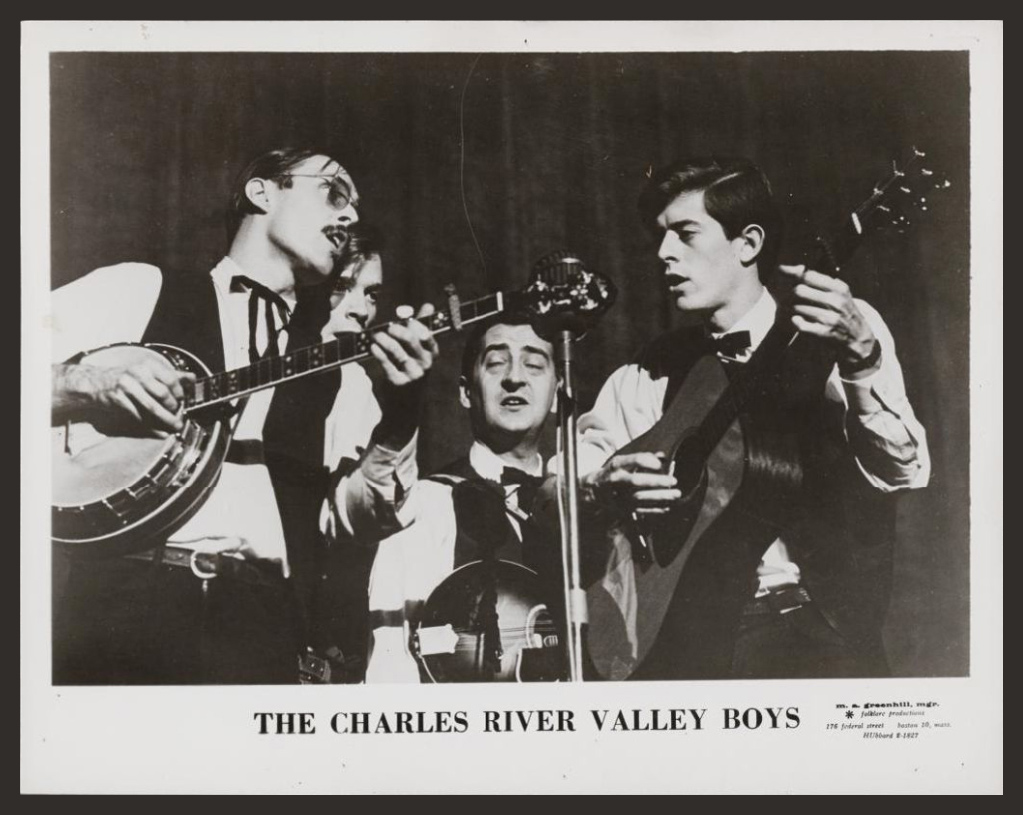

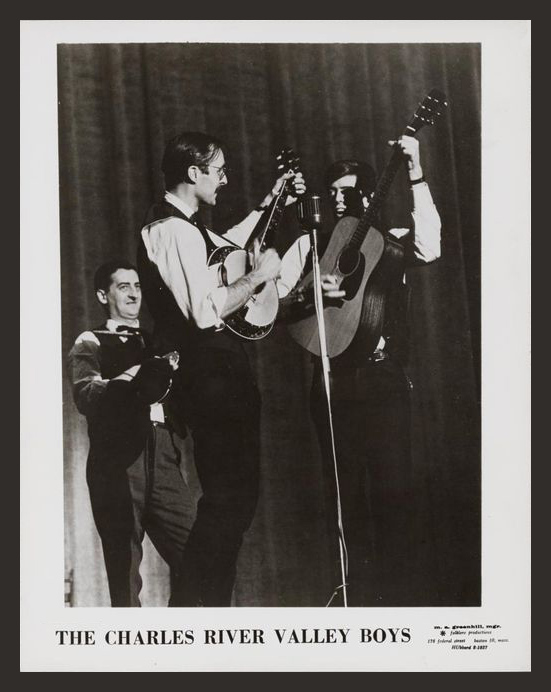

Formed in 1959 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the group’s original lineup featured Nebraska native Bob Siggins, a banjo player studying at Harvard, Ethan Signer, a Yale graduate who played guitar, mandolin and autoharp and was in a master’s program at MIT, and Eric Sackheim, a Harvard student from New York who played guitar and mandolin. With each of the trio on vocals and the group’s name being a pun on the North Carolina-based Laurel River Valley Boys, the band debuted at Harvard’s Lowell House Dining Commons that year and quickly gained attention through frequent appearances on Balladeers and Hillbilly at Harvard, popular radio shows on Harvard’s WHRB.

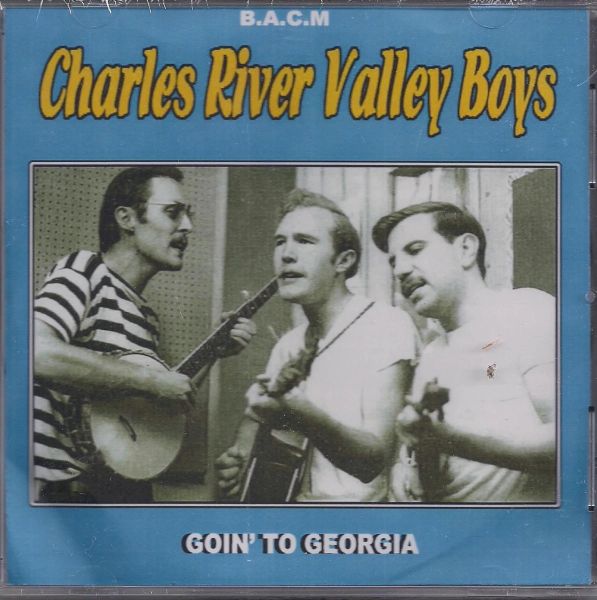

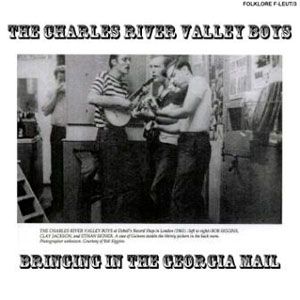

Bringin’ In The Georgia Mail, Blue Grass And Old Timey Music

In 1960, TCRVB landed a regular gig at Tulla’s Coffee Grinder in Harvard Square and in early 1961 they self-released Bringin’ In The Georgia Mail, recorded in Cambridge and London. Later that year, Folklore Records issued the disc in the UK on the Folklore label, making them almost as popular in Old England as they had become in New England. By 1962, the group was playing weekly at Club Mount Auburn 47 – which became Club 47 in 1963 and Club Passim in 1969 – and they continued to do so through 1966.

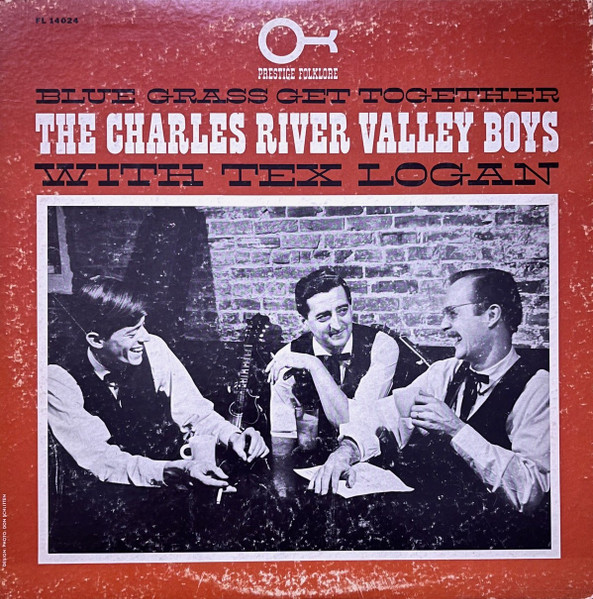

In 1962, Mt. Auburn Records released TCRVB’s aptly named LP Blue Grass And Old Timey Music, produced by Paul Rothchild, a rep for Boston-based Dumont Record Distributors. After he moved to Prestige Records in 1964, he produced the group’s third album, Blue Grass Get Together, which featured fiddler Tex Logan.

Lineup changes, Growing popularity, New York City debut

At the end of 1963, Sackheim left the group to study in Europe and the band became a quartet, with original members Siggins and Signer joined by washtub bassist Fritz Richmond, a Newton, Massachusetts, native and guitarist John Cooke, son of the British-American journalist and PBS television personality Alistair Cooke.

In December 1962, TCRVB appeared at the Boston Folk Showcase at Bates Hall Theatre in Boston and between 1963 and 1965, in addition to their standing gig at Club 47, they performed at Chum’s Coffeehouse in Waltham, Massachusetts, the Moon-Cusser Café on Martha’s Vineyard and Bennet Hall on Nantucket. In the summer of 1963, when they were featured in a full-page article in the Cambridge-based folk paper The Broadside, the group played at the Hatch Memorial Shell in Boston and did a two-night stand at Gerde’s Folk City, their New York debut. In September, they appeared at Carnegie Hall alongside Pete Seeger, Rev. Gary Davis, Hally Wood, Tony Kraber and Will Geer.

Newport Folk Festival debut, More lineup changes

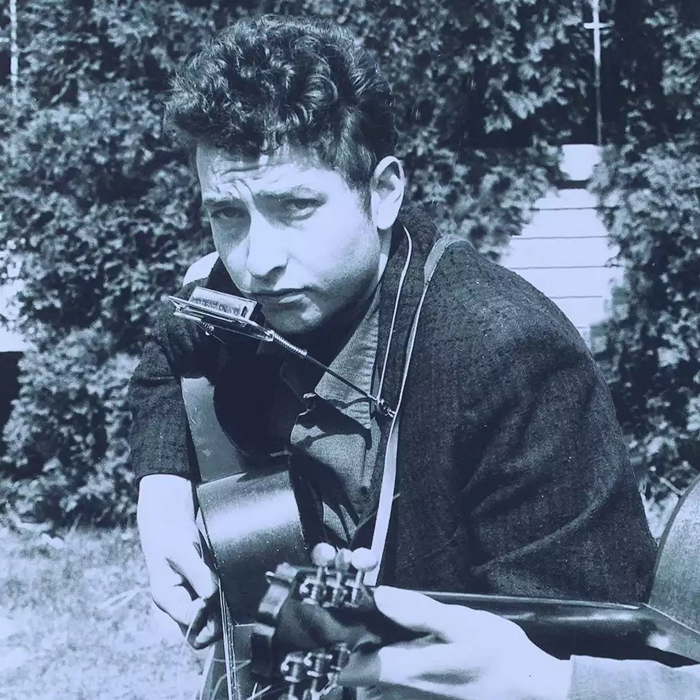

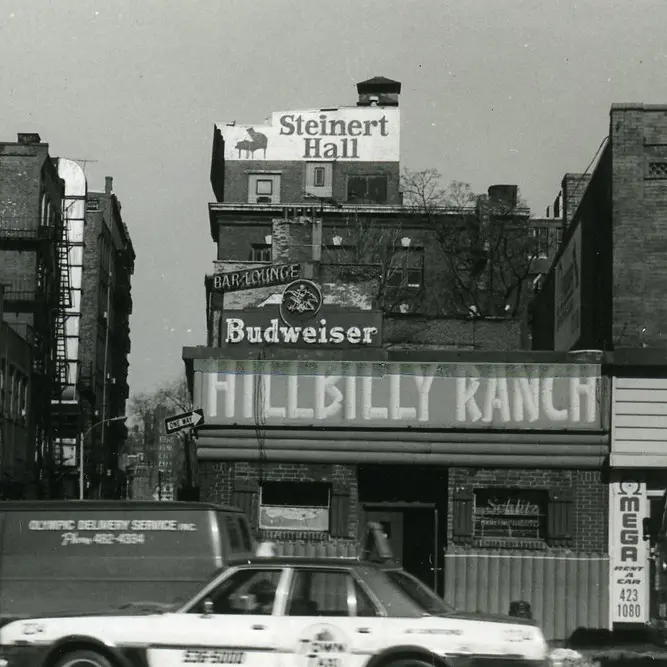

In 1965, the group debuted at the Newport Folk Festival – the same year Bob Dylan “went electric” to the shock and outrage of folk traditionalists – and in 1966 their lineup changed again, with Signer, Cooke and Richmond leaving the band. The re-formed quartet included founding member Siggins, Everett, Massachusetts, native Joe Val on mandolin – plus his unforgettable high-tenor voice – Jim Field on guitar and Everett Allen Lilly on bass. All experienced performers, Val had played with the Berkshire Mountain Boys, Field with the New York Ramblers and Lilly’s father founded the Lilly Brothers, with whom he often sat in at the Hillbilly Ranch in Boston.

Beatle Country

In 1966, when their producer Rothchild joined Elektra Records, the group sent him a four-song demo with bluegrass versions of two recently released Beatles songs, “I’ve Just Seen a Face” and “What Goes On.” Rothchild suggested the band record an entire album of Fab Four songs since in 1965 Elektra had released The Baroque Beatles Book, a collection of Beatles tunes orchestrated in Baroque style that sold well. After Elektra founder Jac Hotzman secured The Beatles’ in-person clearance for the new project in London, in September the band recorded Beatle Country in Nashville with West Virginian Craig Wingfield on dobro, Californian Eric Thompson on guitar and A-list Nashville session player Buddy Spicher on fiddle.

Released in November 1966, the 12-track album had a modicum of commercial success but its greatest legacy is that it helped to nurture the Boston-area folk scene by blending pop and bluegrass, a genuinely trailblazing move that no other band had attempted on nearly such a bold level. Having attracted a far broader audience with the album, the group maintained its regular Club 47 schedule while also expanding outside the Boston-Cambridge area, playing at Y-Not Coffeehouse in Worcester, doing multi-night gigs at The Second Fret in Philadelphia and making their first West Coast appearances at Jabberwock in Berkeley and the Berkeley Folk Festival in the summer of 1966.

Disbanding, Reissues, Compilations

Though Beatle Country helped ignite an explosion of other multigenre Beatles cover albums – including Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops Play the Beatles in 1971 – it was The River Valley Boys’ last studio outing and the group broke up in late 1968. They played their final show at the Sanders Theatre in Cambridge in November that year.

By the time TCRVB split, Beatle Country had become a highly sought-after collectors’ item – selling for as much as $75 (about $650 in 2023) – until Rounder Records reissued it in 1995. In 2003, the British label Prestige Elite released a definitive 30-song compilation of the group’s pre-Beatle Country recordings called Bluegrass And Old Timey Music, featuring all the songs from the 1962 album of the same name and 1964’s Blue Grass Get Together.

Siggins’ comments on Beatle Country

Speaking of the group’s groundbreaking decision to record Beatle Country – far and away their best-known album – Siggins said the basic elements of TCRVB and The Beatles were more similar than most people knew or were willing to admit. “A lot of the folkies were into the Beatles big time, on the sly if nothing else, including us,” he said. “As we got into learning the songs, we discovered that the singing they did lent itself well to bluegrass harmonies, which we liked to kind of layer on top of the lead vocal. And they did some kind of similar things.”

(by D.S. Monahan)