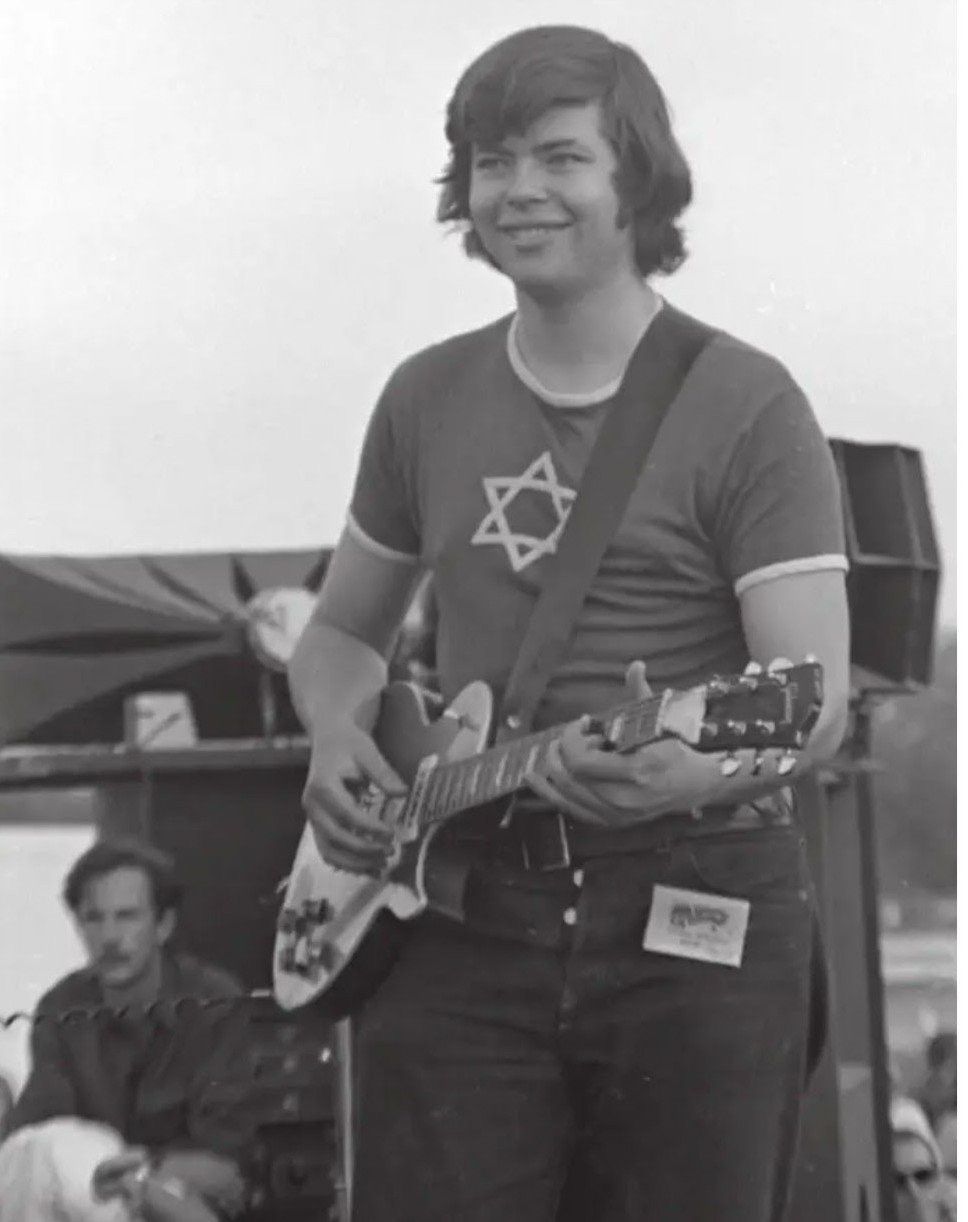

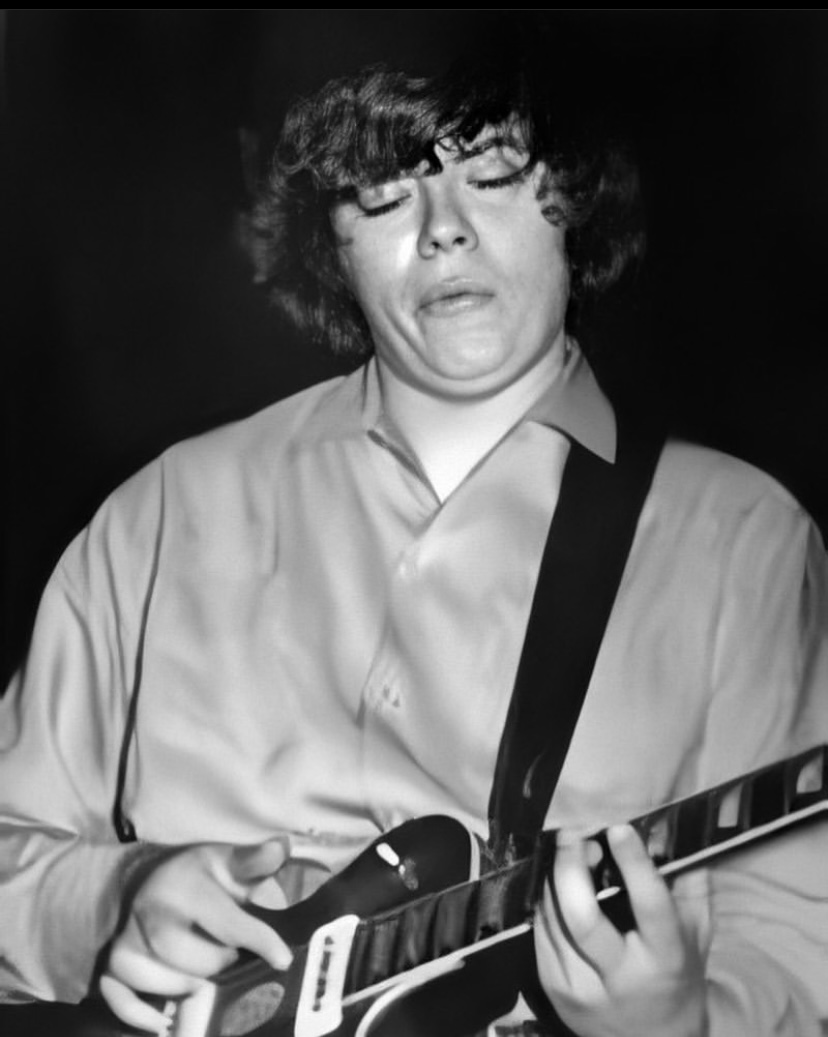

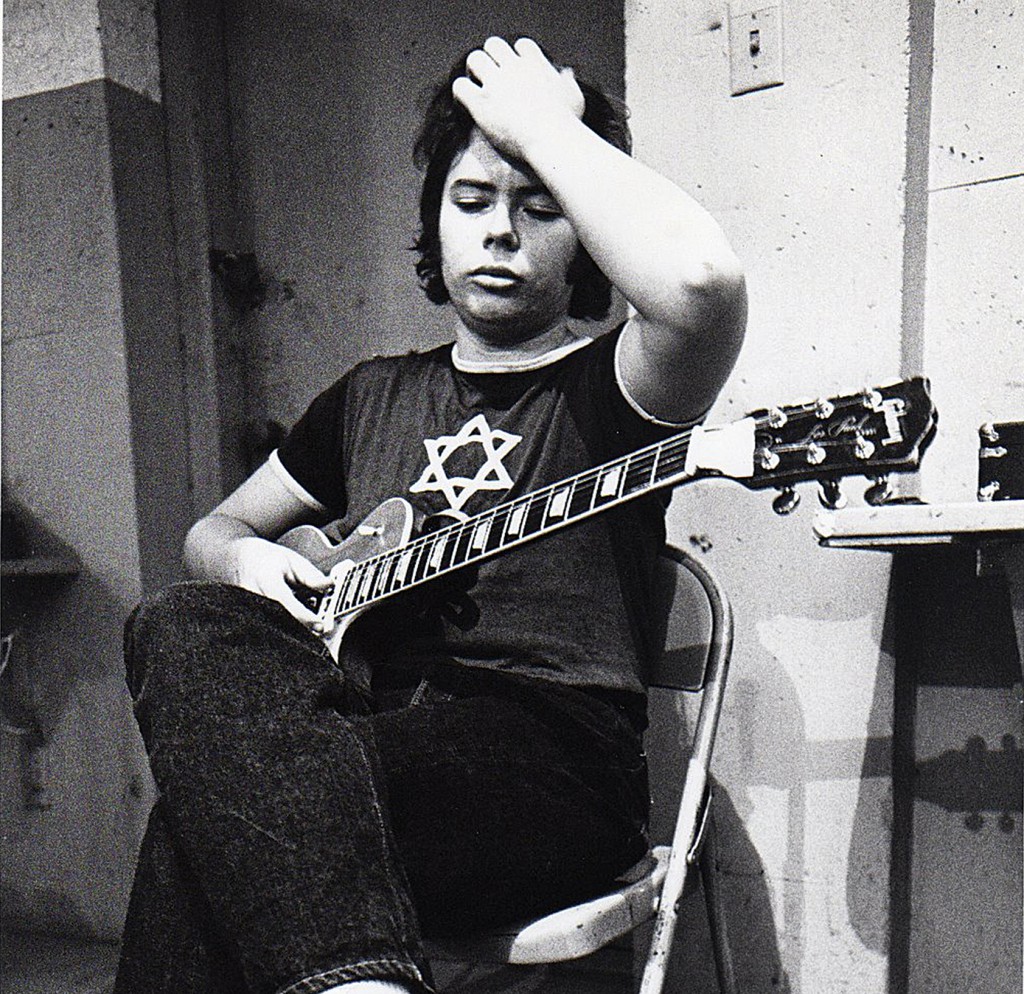

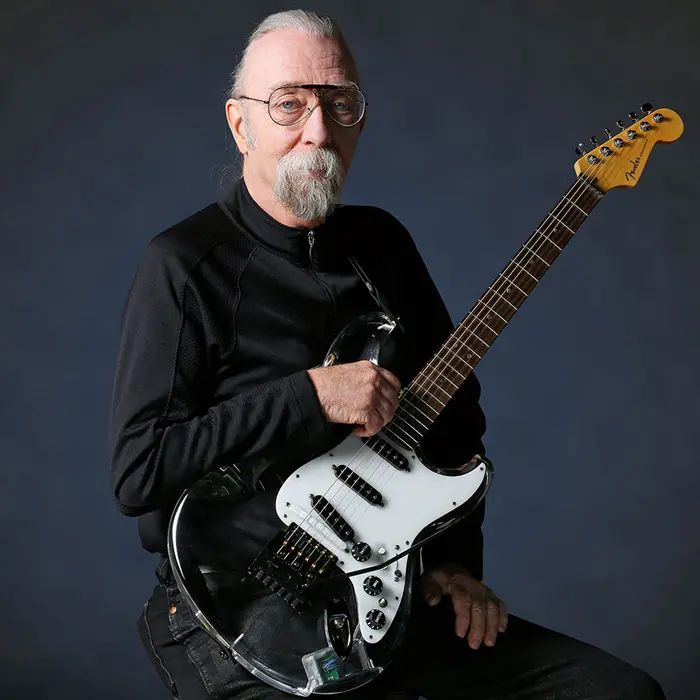

Alan ‘Blind Owl’ Wilson

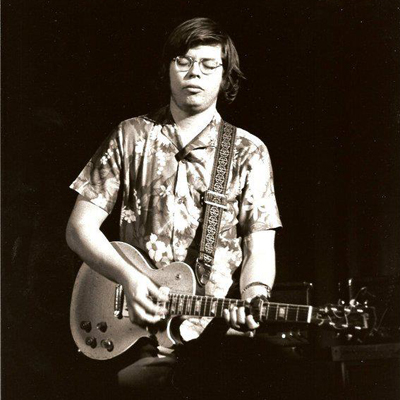

With a voracious appetite for the blues, a scholarly approach to researching the genre’s history and an unmistakable voice respected not for high-note heroics but for soul-searching sincerity, Alan Wilson was as inimitable and unforgettable a figure as rock ‘n’ roll has ever produced. And he left a lasting legacy that belies his fleeting foray into the superstar spotlight.

A pioneer of blues-rock in a musically transformational era when psychedelia was king, Wilson was instrumental in introducing authentic blues to a generation of his peers, many of whom knew nothing about non-white artists that weren’t signed to Motown. And in co-founding and fronting the seminal ‘60s band Canned Heat, he had as much to do with the development of rock as other harp-blowing blues-rock icons like Brian Jones, John Mayall, Paul Butterfield and Magic Dick. Though his recording career lasted only four years, Wilson’s influence is so deeply embedded in modern rock’s cement that it’s very often – and very unfairly – overlooked.

MUSICAL BEGINNINGS

Born Alan Christie Wilson on July 4, 1943 in Arlington, Massachusetts, Wilson’s mother and stepfather were amateur pianists, the latter having taught music in a New York City school district, and his extraordinary musical gifts were apparent in early elementary school. By age 12, he was beyond proficient on the trombone – his earliest musical love being horn-fueled New Orleans jazz as personified by Sidney Bechet, Louis Armstrong and Al Hirt – and in high school he formed The Crescent City Hot Five, a combo in which he rearranged jazz standards and tutored his bandmates on their parts when he wasn’t playing chess or tennis, his favorite non-musical pastimes.

DISCOVERING THE BLUES

At around age 16, Wilson discovered the blues when a friend played him The Best of Muddy Waters (Chess, 1958) and he set to devouring the work of Waters, Son House, Robert Johnson, Tommy Johnson, Charley Patton, Skip James, Bukka White, Little Walter and John Lee Hooker, teaching himself guitar and harmonica – Hooker being the inspiration for the former, Little Walter for the latter – while stepping away from the sounds of Bourbon Street toward the grit and soul of the Mississippi Delta. Soon he stopped playing trombone to focus on developing his bottleneck guitar and harmonica skills, expanding his musical diet to include classical, gospel, raga and bhangra.

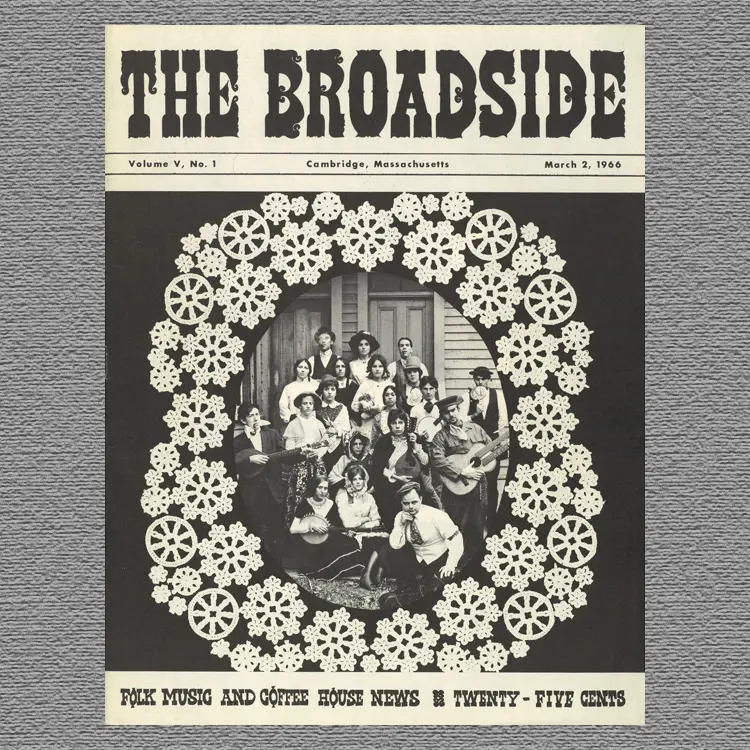

BOSTON UNIVERSITY, MUSIC JOURNALISM

In 1961, after graduating from Arlington High School and receiving a National Merit Scholarship and an F.E. Thompson Scholarship from the Town of Arlington, Wilson enrolled at Boston University, majoring in music and writing articles for Cambridge-based folk weekly The Broadside and other papers. Halfway through his second year at BU, he dropped out to concentrate on playing music rather than studying it, working as a bricklayer and giving occasional harmonica and guitar lessons.

EARLY PERFORMANCES, MISSISSIPPI JOHN HURT

In 1962, Wilson met fellow blues enthusiast, Boston native and Harvard student David Evans and the duo began playing the local coffeehouse circuit, Evans on guitar/vocals and Wilson on guitar/harmonica, covering blues-folk standards at places like Club Mount Auburn 47 (later Club 47). By 1963, Wilson’s harmonica style and high-pitched tenor – modeled after that of Mississippi-born bluesman Skip James – had gained so much renown that he was invited to perform with 72-year old blues icon Mississippi John Hurt on harmonica at a Cambridge show before Hurt appeared at the Newport Folk Festival that year.

SON HOUSE COLLABORATION

In 1964, before 63-year old Son House appeared in Cambridge after decades of heavy drinking and not performing, Wilson helped him to relearn his songs and House went on to play at Newport that summer. “He taught Son House how to play Son House,” said House’s manager Dick Waterman, a Plymouth, Massachusetts, native. Wilson played on two tracks of House’s Father of Folk Blues (Columbia, 1965) and on his live LP Delta Blues and Spirituals (Capitol, 1995, recorded in 1970).

MOVE TO LOS ANGELES, BECOMING “BLIND OWL”

In early 1965, Wilson met John Fahey, a UCLA graduate student writing his thesis on Charlie “Father of the Delta Blues” Patton, who invited Wilson to Los Angeles to help with research. The extremely nearsighted Wilson forgot to take his glasses on the ensuing road trip and Fahey nicknamed him “Blind Al” after blues greats like Blind Lemon Jefferson, Blind Willie Johnson and Blind Blake, which soon evolved into “Blind Owl” based on Wilson’s round facial features and academic nature.

CO-FORMING CANNED HEAT

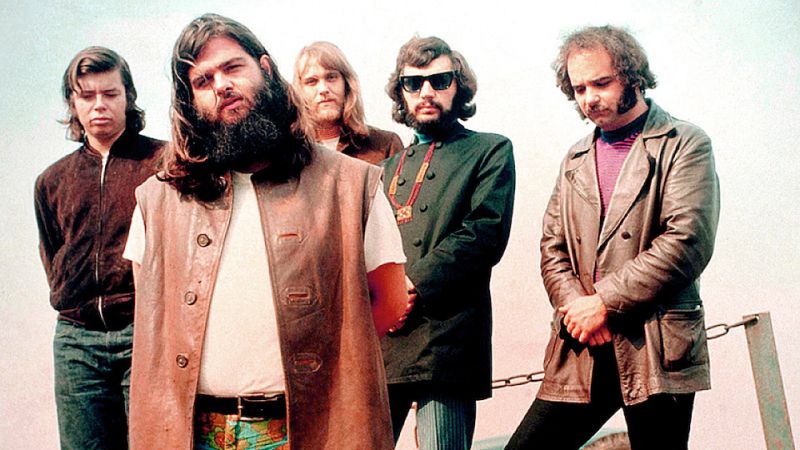

Shortly after arrival in LA, Fahey introduced 21-year old Wilson to 22-year old Bob “The Bear” Hite, a record store manager with a massive collection of blues 78s – 15,000, he claimed – and a classic “belter” singing style akin to Big Joe Turner’s that made him the perfect musical foil to Wilson. The odd-couple combo of Hite’s unlimited extroversion and Wilson’s lifelong introversion formed the bedrock of what would become Canned Heat.

In late 1965, after playing in a short-lived jug band with Fahey, Wilson and Hite co-formed The Canned Heat Blues Band – named after Tommy Johnson’s 1928 song “Canned Heat Blues,” about an alcoholic who drinks Sterno (a denatured alcohol used as cooking fuel) – with lead guitarist Mike Perlowin, bassist Stu Brotman and drummer Keith Sawyer. Perlowin, Brotman and Sawyer left soon after the name was shortened to Canned Heat, replaced by Henry “The Sunflower” Vestine (from The Mothers of Invention), Larry “The Mole” Taylor and Frank Cook.

EARLY GIGS, FIRST DEMO

In mid-1966, after the band had gigged for about six months at colleges, private parties and small clubs, Hollywood agent Skip Taylor became their manager. An enormously successful discoverer of blues and soul acts including Big Mama Thornton, Etta James and Jackie Wilson, Taylor booked the group time at El Dorado Studios in LA where they recorded 10 demos, issued in 1970 as Vintage Heat by Janus Records.

Throughout 1965/66, the band’s gigs were infrequent and poorly attended. “The first year we were together, we’d get a gig, play three days and get fired…because we refused to be a human jukebox,” Wilson told Melody Maker in 1969. Frustrated by the public’s indifference, the group broke up in August 1966 before reforming in November when, while playing at The Ash Grove in LA, they caught the attention of Jackie DeShannon, wife of Liberty Records’ A&R chief Irving “Bud” Dain, who signed them within a week.

MONTEREY POP FESTIVAL, DEBUT ALBUM

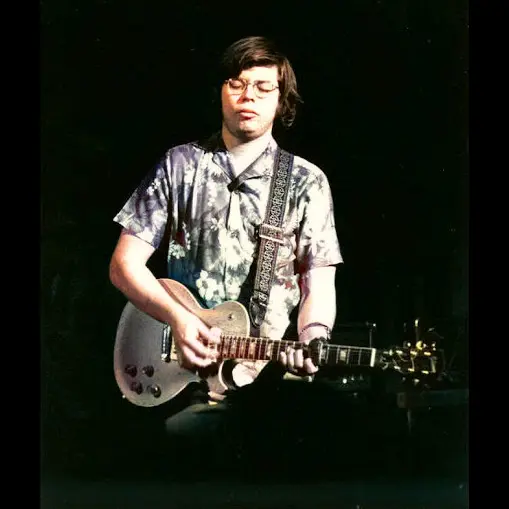

On June 17, 1967, three weeks before Liberty released their debut album, Canned Heat appeared at the Monterey Pop Festival and received effusive critical acclaim; a review in DownBeat called Wilson and Vestine “quite possibly the best two-guitar team in the world” and said Wilson “has certainly become our finest white blues harmonica man.”

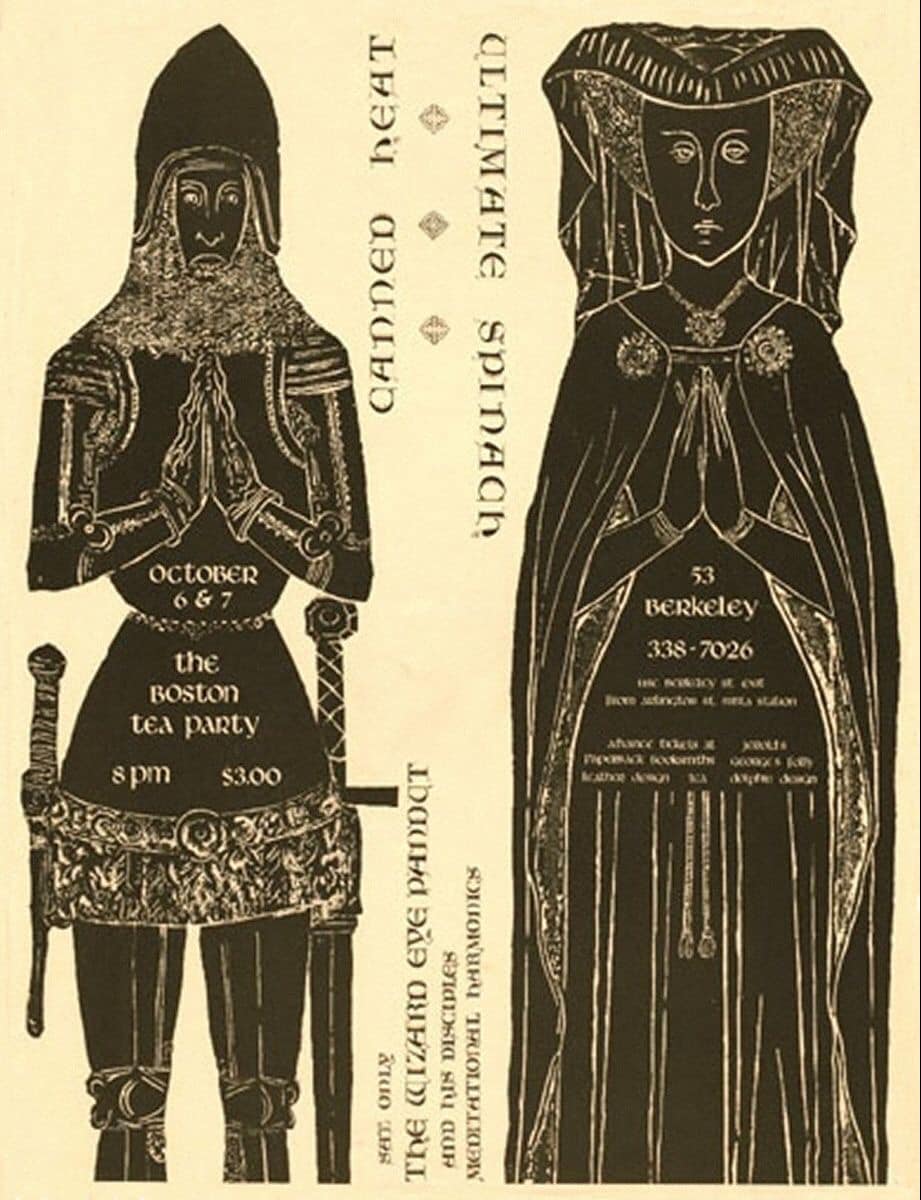

In July, Liberty released the band’s eponymous debut, an 11-track reworking of blues standards – no originals – on which Wilson sang lead on one song and Hite handled the rest. The supporting tour included four shows at The Boston Tea Party and in November Cook left the group, replaced by Adolfo “Fito” de la Parra, a Berklee graduate who had formed his first band with Jeff “Skunk” Baxter when they were boyhood friends in Mexico.

BOOGIE WITH CANNED HEAT

In November 1967, with de la Parra, the group recorded their second LP, Boogie with Canned Heat, which Liberty released in January 1968. The album included “On the Road Again,” Wilson’s updated version of a 1953 song by Chicago bluesman Floyd Jones, which reached #16 in the Billboard Hot 100 and #8 in the UK. In addition to singing lead, Wilson played guitar, harmonica and tamboura on the track. Now the hippie generation’s kings of boogie-woogie, the group became the de facto house band at The Kaleidoscope in LA, played at the Newport Pop Festival and made their first of multiple UK/Europe tours.

LIVING THE BLUES, HALLELUJAH

In October 1968, Liberty issued Canned Heat’s third effort, Living the Blues, which featured “Going Up the Country,” Wilson’s very-slightly revised rendition of Henry Thomas’ “Bull-Doze Blues” (1929). The track reached #11 in the Billboard Hot 100, #19 in the UK and became the unofficial anthem of Woodstock the following year. In July 1969, Liberty released the band’s fourth LP, Hallelujah, a 10-track collection of mostly originals (four credited to Wilson).

WOODSTOCK APPEARANCE, LINEUP CHANGES

Vestine left the group immediately after the album’s release, replaced by Harvey Mandel, and on August 16 the band played at Woodstock. In the fall of 1969, frustrated with touring and increasingly isolating himself from the band, Wilson quit Canned Heat for two weeks before his bandmates convinced him to return. In May 1970, Taylor and Mandel left the group and Vestine returned along with bassist Antonio de la Barreda.

LIVE IN EUROPE, FUTURE BLUES, HOOKER ‘N HEAT

In June 1970, Liberty and United Artists issued Canned Heat ’70 Concert Live in Europe, later renamed Live in Europe, which went to #15 in the UK. The band followed with their fifth studio album, Future Blues, which Liberty released in August 1970.

An eight-song LP with five originals, Future Blues included a cover of Wilbert Harrison’s “Let’s Stick Together” that hit #26 in the Billboard Hot 100 and #2 in the UK Singles chart, the band’s only top-40 hit on which Hite sings lead. The cover art – astronauts placing an upside-down American flag on the moon – was Wilson’s idea, part of his lifelong environmentalism as evidenced by songs like “Poor Moon” and Music Mountain, a non-profit he established for the preservation of California’s coastal redwoods.

In the summer of 1970, the group collaborated with John Lee Hooker – who reportedly called Wilson “the greatest harmonica player ever” – and the result was the double album Hooker ‘n Heat, which Liberty issued in January 1971. The LP went to #73 in the Billboard 200, Hooker’s first time on the chart.

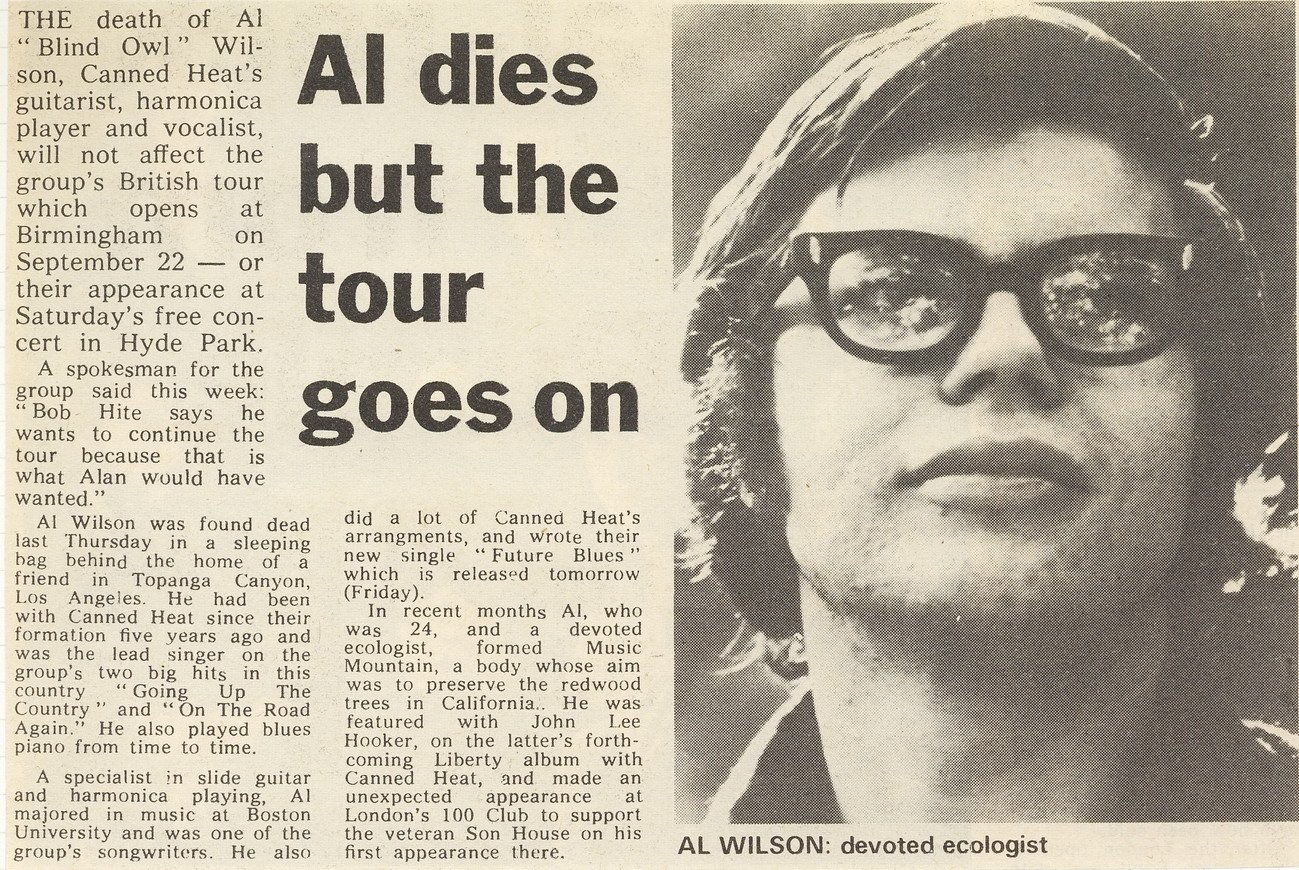

DEATH, POST-WILSON CANNED HEAT

On September 3, 1970, Wilson was found dead in Hite’s backyard in Topanga Canyon at age 27 – two weeks before Jimi Hendrix and four weeks before Janis Joplin died at the same age – with the cause of death ruled as “accidental acute barbiturate intoxication.” The day before, when he didn’t show up at the airport to embark on a scheduled UK/Europe tour, the rest of the band boarded without him, unalarmed by his absence since Wilson was often late for rehearsals and other scheduled meetings.

Canned Heat continues touring and recording to this day, having made 11 albums since Wilson’s death. Since Hite’s passing in 1981, there have been four vocalists amidst a revolving door of other members, but de la Parra remains in the band 56 years after joining.

BIOGRAPHY, BLUES HALL OF FAME, THE BLIND OWL

In 2007, Lulu Press published Rebecca Davis Winter’s biography Blind Owl Blues: The Mysterious Life and Death of Blues Legend Alan Wilson. In 2013, Wilson was induced in the Blues Hall of Fame in Memphis and Severn Records issued the two-CD set The Blind Owl – the most comprehensive selection of his material ever released – which includes 20 tracks, 14 of them Wilson originals.

(by D.S. Monahan)