Mission of Burma

What do you call a post-punk four-piece that had a tape manipulator/sound engineer as a full-time member, incorporated Beatle-esque melodies into songs better than any other band in the genre and had a name that was an obscure historical reference to a British Army captain’s 1885 expedition to an impoverished agrarian nation in Southeast Asia?

Innovative? Yep. Imaginative? Yessir. Intelligent? You betcha. Mission of Burma? You got it.

OVERVIEW

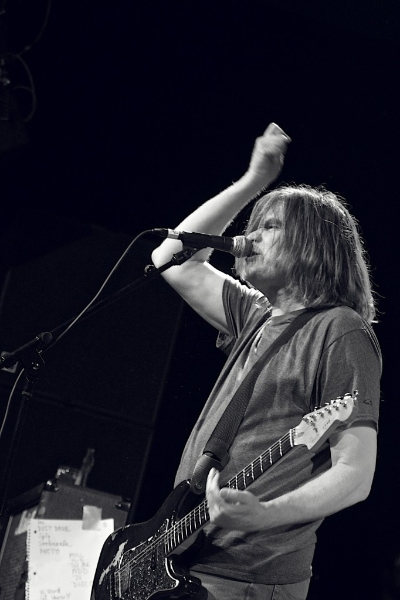

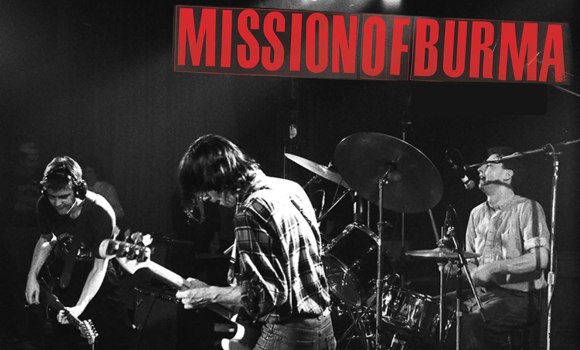

Unpretentiously avant-garde, MoB is widely cited as the most influential post-punk band to come out of Boston, credited for galvanizing the nascent alt-rock movement and establishing the gold standard for that genre in terms of all-around artistic audacity and fist-in-your-face ferocity.

Using a blend of looped sonic texturing, brain-rattling volume, riveting melodic variations, jarring time-signature shifts and live shows so physical that audiences felt almost assaulted, MoB’s original lineup lasted just four years – producing one single, one EP and one LP – but the band’s fury-fueled battering ram of explosive energy and self-evident smarts smashed down doors for groups like Nirvana, Hüsker Dü, The Replacements, Pearl Jam, Throwing Muses and Pixies. After a 19-year hiatus, MoB’s second incarnation stayed together for 17 years, recorded four albums and reaffirmed the band’s monumental impact and iconic status with authority.

FORMATION, EARLY APPEARANCES

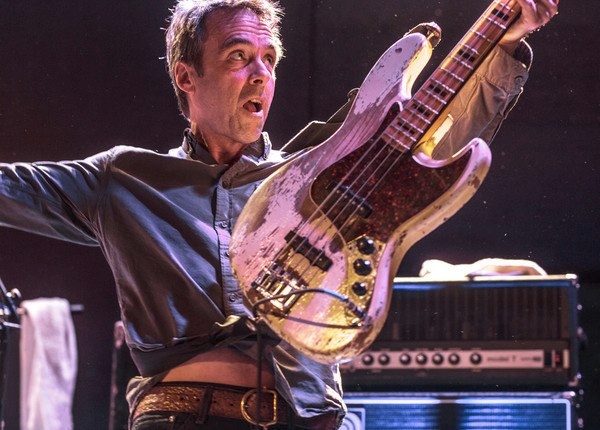

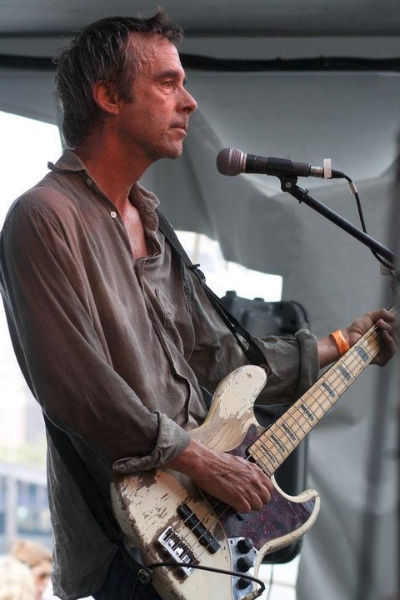

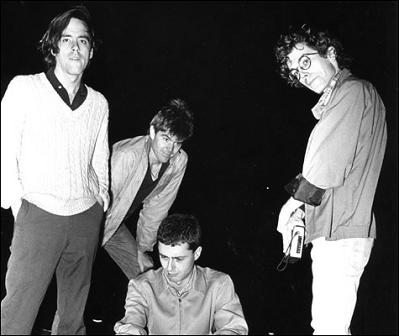

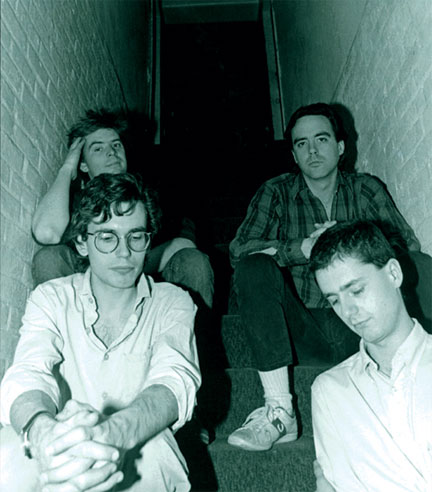

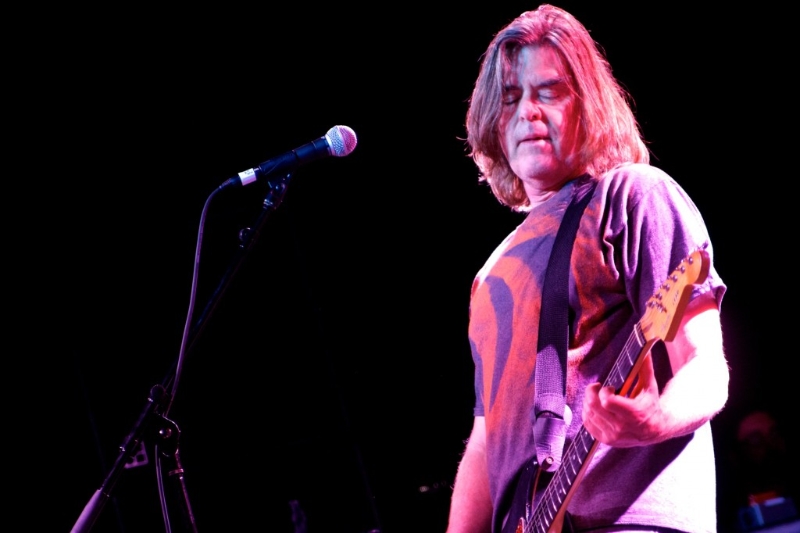

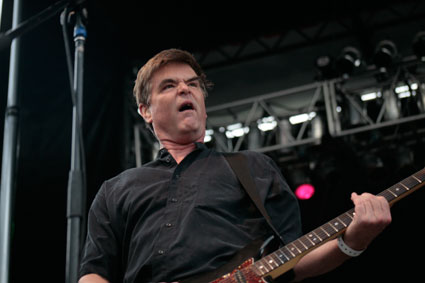

MoB formed in 1979 following the break-up of the Boston-based rock-synthpop group Moving Parts when that band’s guitarist Roger Miller – who moved to Boston from Michigan and also played piano and trumpet at some MoB gigs – and bassist Clint Conley, a Connecticut native, added drummer Peter Prescott, a Boston native who’d played with local punk band The Molls. Named after a plaque Conley had seen in a diplomatic building once and with Miller and Conley doing most of the songwriting, the trio made their debut at The Modern Theatre in Boston on April Fool’s Day that year.

Shortly after that gig, Miller wrote the song “Nu Disco” and, thinking it would sound cooler with tape looping, contacted Martin Swope, a sound engineer who’d also relocated to Boston from Michigan and with whom Miller had worked previously on pieces inspired by avant-garde composers John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen. Soon he became the group’s fourth member and an essential element of the band’s pioneering sound. Swope appeared onstage very rarely and only during encores, during which he played rhythm guitar instead of his usual job, looping and modulating the band’s sound at a mixing desk in the wings.

Exactly one month after the trio made its debut, the now four-member MoB played a two-night stand at The Space in Boston, becoming a regular act there through 1981 while also performing frequently at Cantone’s, The Club and The Rathskeller in Boston and playing shows at the Paradise Rock Club, The Underground, The Channel, Spit, 1270 Club and the Bradford Ballroom, Jonathan Swift’s and Inn-Square Men’s Bar (Cambridge), Jasper’s (Somerville), The Space (Worcester), The Main Act Concert Club (Lynn) and The Living Room (Providence). In April and September 1980, MoB played live on WERS, Emerson College’s radio station.

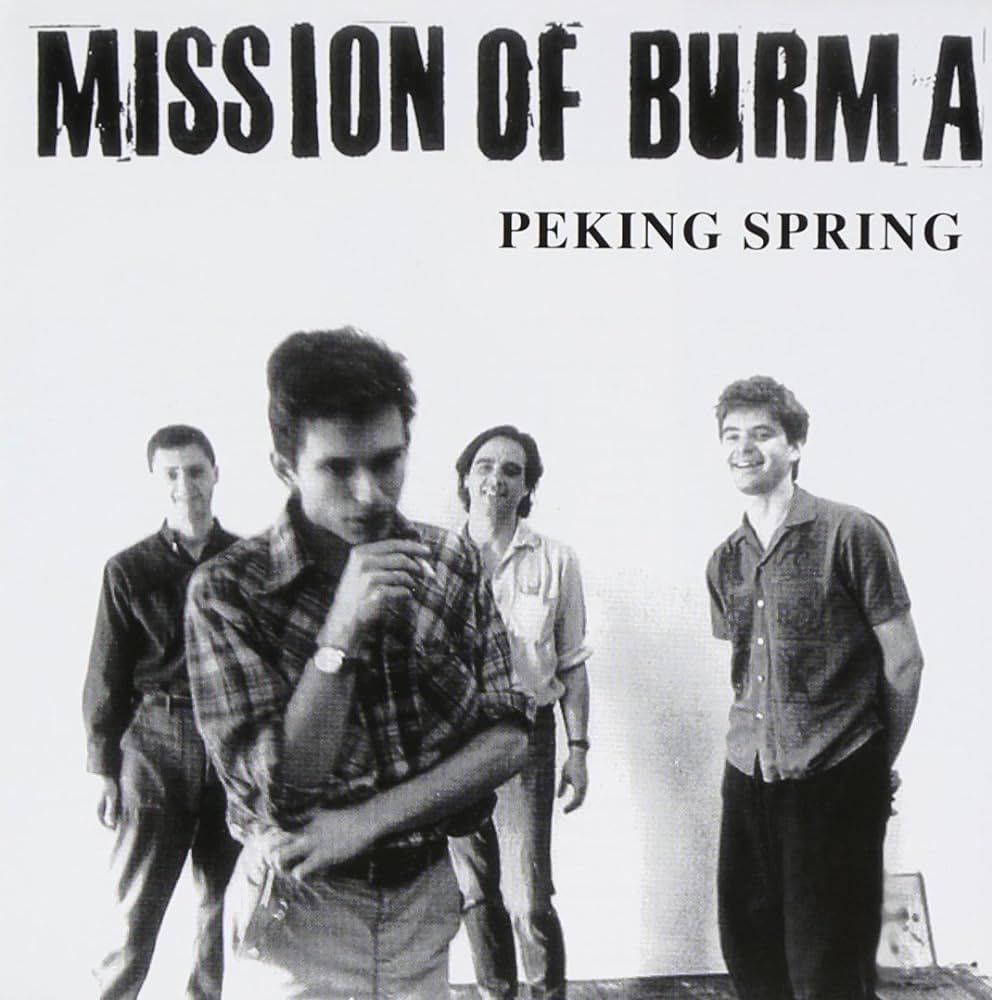

ACE OF HEARTS SIGNING, SIGNALS, CALLS AND MARCHES, DEBUT ALBUM

By the end of 1980, MoB had also played shows at CBGB and Max’s Kansas City in New York, and in mid-1981 they signed with the Boston-based record label Ace of Hearts. In June, they recorded Conley’s “Academy Fighting Song” as a single with Miller’s “Max Ernst” as the B-side and, though the band initially thought Rick Harte’s production didn’t reflect the group’s on-stage intensity, the single’s rapid sales assured them that Harte was on the right track.

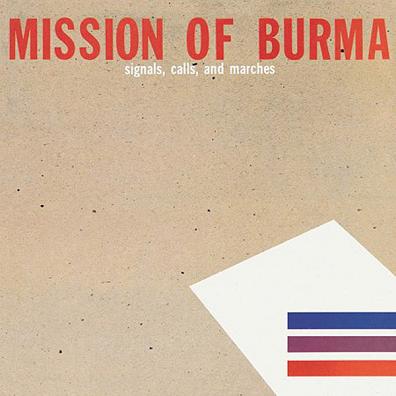

In July 1981, MoB’s six-song EP Signals, Calls and Marches hit the shelves, selling out its initial 10,000-unit pressing by the end of that year. To support the disc, they debuted on the West Coast, played their first non-domestic gig in Toronto and toured the East Coast including performances at Boston nightclubs Streets and Metro, the MacPhie Pub (Medford), Uncle Sam’s (Nantasket Beach), Ralph’s Rock Diner (Worcester), Club Infinity (Springfield), Club Casino (Hampton Beach) and Lupo’s Heartbreak Hotel (Providence).

In 1982, MoB released their first full-length album, Vs., which critics praised as “ambitious” and “powerful” and embarked on a cross-country North American tour that included the Paradise, The Channel, Jonathan Swift’s, Jasper’s, The Rusty Nail (Sunderland), Exit 13 (Worcester), the Great American Music Hall (New Haven), The Lit Club (Hartford) and The Living Room plus on-campus shows at MIT, Brown, Wellesley, Clark, Bowdoin and Middlebury.

DISBANDING, THE HORRIBLE TRUTH ABOUT BURMA, MISSION OF BURMA

In early 1983, MoB announced that they were disbanding, largely because Miller had a developed a serious case of tinnitus, which causes a constant ringing in the ears and was diagnosed as being the result of band’s often excruciatingly loud live shows. At their final gigs in March that year, Miller wore foam earplugs and rifle-range headphones onstage. In 1985, Ace of Hearts released a compilation of the band’s notoriously spotty and chaotic 1983 shows, The Horrible Truth About Burma, and in 1988 Rykodisc released the compilation Mission of Burma.

EXPANDING FANBASE

Ironically, MoB’s fanbase expanded dramatically after the band split as Taang! and Rykodisc reissued the band’s Ace of Hearts catalogue and previously unreleased material. In 1991, the band achieved almost instant legend status when their story was featured in the book Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes from the American Indie Underground, 1981-1991 along with 12 other groups including Dinosaur Jr. The band’s catalogue got fresh attention in 1989 when REM released their cover of “Academy Fight Song,” followed by Moby’s 1996 rendition of “That’s When I Reach for My Revolver” from MoB’s 1981 EP.

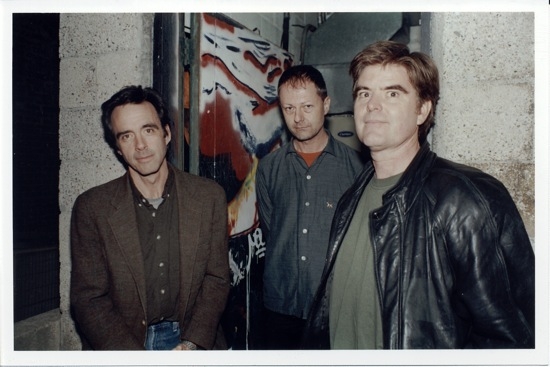

REUNION, LATER ALBUMS, SECOND DISBANDING

In December 2001, MoB’s reunion was set in motion when Miller and Conley sat in with Prescott’s band Peer Group at the Knitting Factory in New York City. The night inspired the trio to plan two MoB shows, one in New York and one in Boston, and when Swoop declined to join they replaced him with Bob Weston – who had played bass in Boston-based Volcano Suns with Preston after MoB broke up In 1983 – on the mixing console. Ticket demand was so strong that the band agreed to two shows in both cities instead of only one.

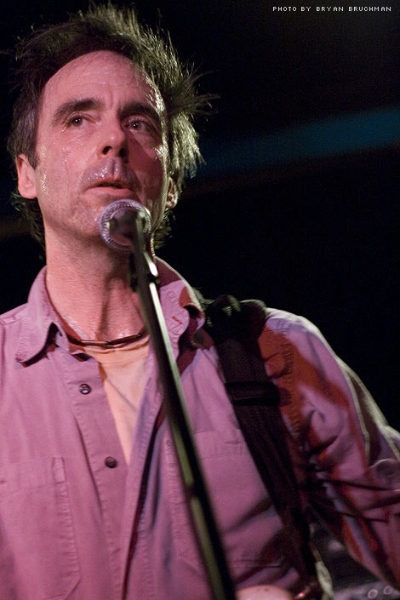

On January 12 and 13, 2002, MoB played at Irving Plaza in Manhattan (formerly The Fillmore New York), followed by shows in Boston on January 18 and 19 at the Avalon Ballroom and the Paradise, after which they decided to reunite, record new material and tour like they had 19 years before. The band recorded ONoffON in 2004 – with one critic saying MoB “sounds as strong as ever (if not stronger)” – and the live album Snapshot, followed by The Obliterati in 2006, which received wide critical acclaim. In 2009 and 2012, the band followed up with The Sound The Speed The Light and Unsound respectively before announcing in 2019 that the group had permanently retired.

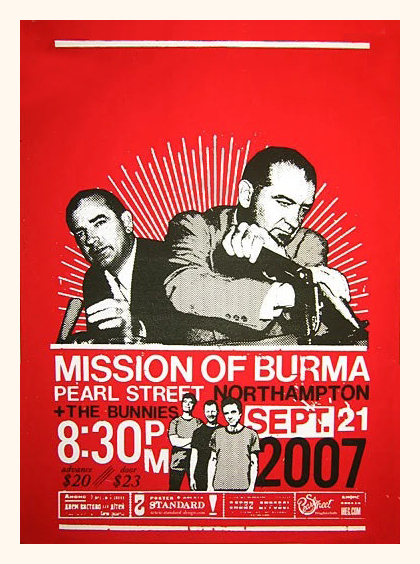

During their reunion years, Mission of Burma did several North American, UK and European tours and played New England venues including Fenway Park (with Foo Fighters), the Fleet Center (formerly Boston Garden), the Paradise, T.T. the Bear’s Place (Cambridge), The Sinclair (Cambridge), the Somerville Theatre, the Regent Theatre (Arlington), 3S Art Space (Portsmouth, New Hampshire) and The Space (Hamden, Connecticut).

DOCUMENTARY, REMASTERS, “MISSION OF BURMA DAY”

In 2006, the 70-minute documentary Not a Photograph: The Mission of Burma Story premiered at the Independent Film Festival Boston, and in 2008 Matador Records released remastered versions of Signals, Calls, and Marches, Vs. and The Horrible Truth About Burma. In 2009, at an official ceremony on the MIT campus, the Boston City Council declared October 4 “Mission of Burma Day” across the city.

CONLEY’S REFLECTIONS

Asked in 2015 why the band became so influential, Conley explained the late-1970s context. “I hear that a lot, and take it as a compliment,” he said. “But I don’t really hear any bands that sound like us. When we formed in ‘79, the punk explosion had happened, but punk vocabulary was primitive. We were part of the expansion of that, using different tonalities and time signatures. We sort of combined the brains of progressive rock and the guts of punk.”

(by D.S. Monahan)