Jim Kweskin & The Jug Band

Jug bands originated in the American South, where groups like Clifford Hayes’ Old Southern Jug Band and Gus Cannon’s Jug Stompers cut their first records in the 1920s (the former in Louisville in 1923, the latter in Memphis in 1927). By by the early ‘40s, however, they’d formed as far north as Chicago and by 1958, when Lyrichord Discs issued the album Skiffle in Stereo by the New York-based Orange Blossom Jug Five, a full-on jug-music revival was underway.

Among that revival’s premiere purveyors was Jim Kweskin & The Jug Band, assembled amidst the maple-lined streets of Cambridge, Massachusetts, hundreds of miles from the tulip trees of Kentucky and the dogwoods of Tennessee but rooted in exactly the same soil: fabulously unfettered fun and acoustical abandon that defied all geographical borders. And the lyrics were as far removed from the political protestations of ‘60s folk icons like Phil Ochs and Joan Baez as Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock” was from Wagner’s Ring Cycle.

With four studio albums, countless live performances and an irrepressibly irreverent musical mélange of hillbilly, country, jazz, ragtime and blues, Jim Kweskin & The Jug Band reminded folkies that music need not be topically tethered to be artistically relevant and creatively cutting edge.

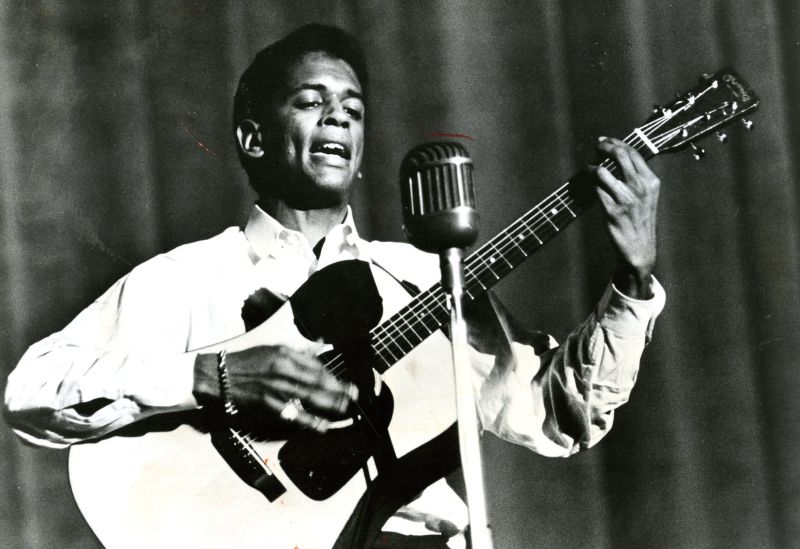

KWESKIN’S ROOTS

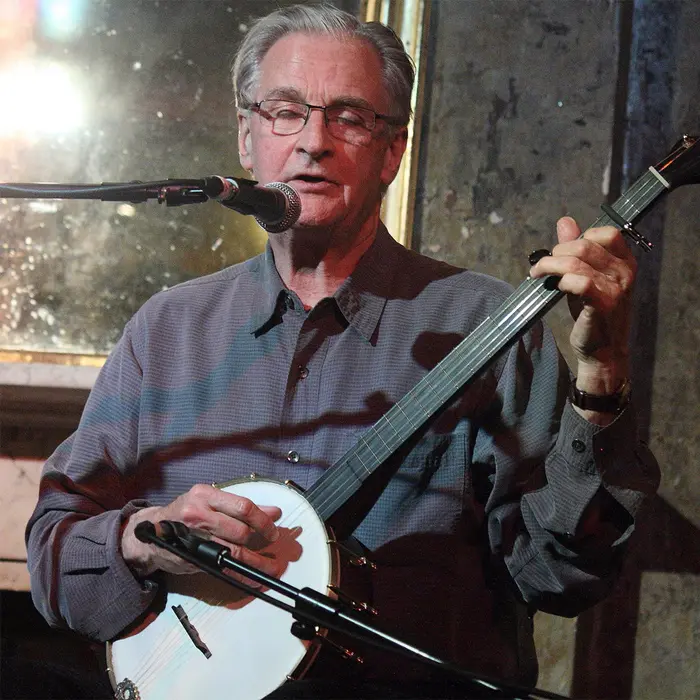

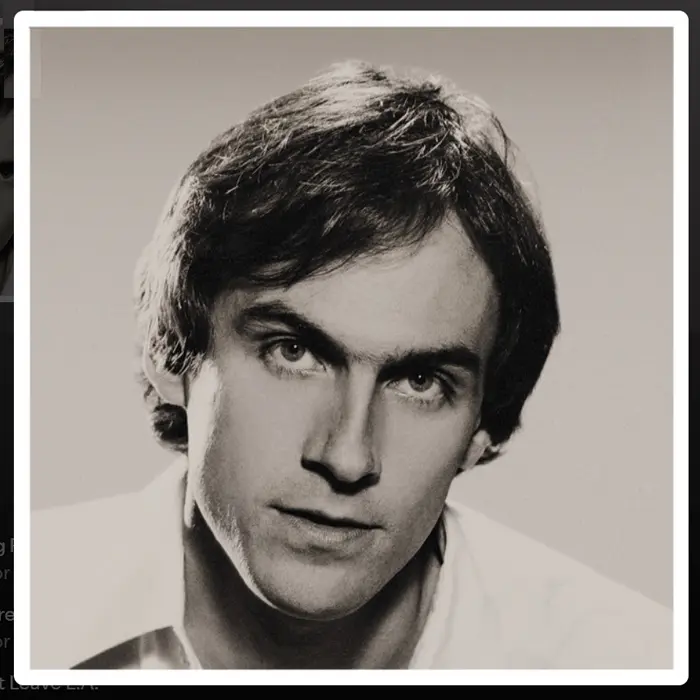

Born July 18, 1940, in Stamford, Connecticut, guitarist-banjoist Kweskin’s original musical passion was jazz, fueled by his father’s collection of 78s. “My father had a collection of old records,” he said in a 2016 interview with The Arts Fuse. “Most of it was early jazz like Jelly Roll Morton, Sidney Bechet, Louis Armstrong’s Hot Fives and Hot Sevens, Bessie Smith, a few Lead Bellys thrown in there, and I loved that music. I just loved it.”

By the time he enrolled at Boston University in 1959, he was also listening to folk, especially Pete Seeger, The Weavers, Burl Ives and Josh White, but it never occurred to him to mix jazz and folk until early 1962 when he saw a later-to-be legend of the genre playing at the very club where he himself would be discovered just one year later. “I heard Eric von Schmidt playing the guitar and singing a Jelly Roll Morton song [“Buddy Bolden’s Blues,” at Club Mount Auburn 47],” he said in the 2016 interview. “And I thought, ‘This is fantastic!’ So that’s what I started to do, and that turns out to be what jug-band music is anyway. It’s really just old-time blues and jazz played on folk-music instruments instead of horns.”

The experience led Kweskin to start developing a ragtime-blues fingerpicking style – inspired by that of Blind Boy Fuller, Mississippi John Hurt, Pink Anderson and others – while spending countless hours researching old-timey recordings from the ‘20s and ‘30s in Boston-area libraries. He also began traveling all over the US in search of the earliest pressings he could find.

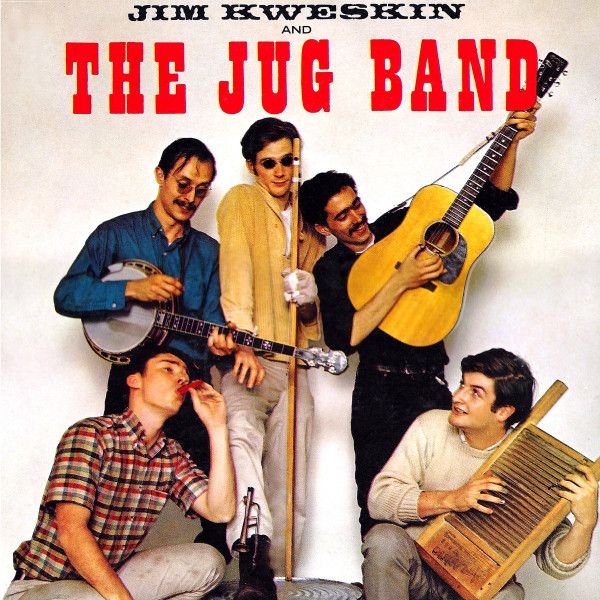

VANGUARD SIGNING, ORIGINAL LINEUP

In early 1963, when The Rooftoppers’ rendition of Gus Cannon’s Jug Stompers’ “Walk Right In” (first recorded in 1929) spent two weeks at #1 in the Billboard Hot 100, Kweskin and some other local musicians began gigging together at popular folk spots like Club 47. Vanguard Records co-founder Maynard Solomon caught one of the informal ensemble’s shows and offered to record them but Kweskin refused for the time being, saying he needed a couple months to put together a proper band. “[Solomon] said, ‘How would you like to make a record with those guys?’ And I said, ‘Well, those aren’t ‘my’ guys, but I’d love to make a record,’” Kweskin said in 2016. “So, basically, I had a record deal before I had the band.”

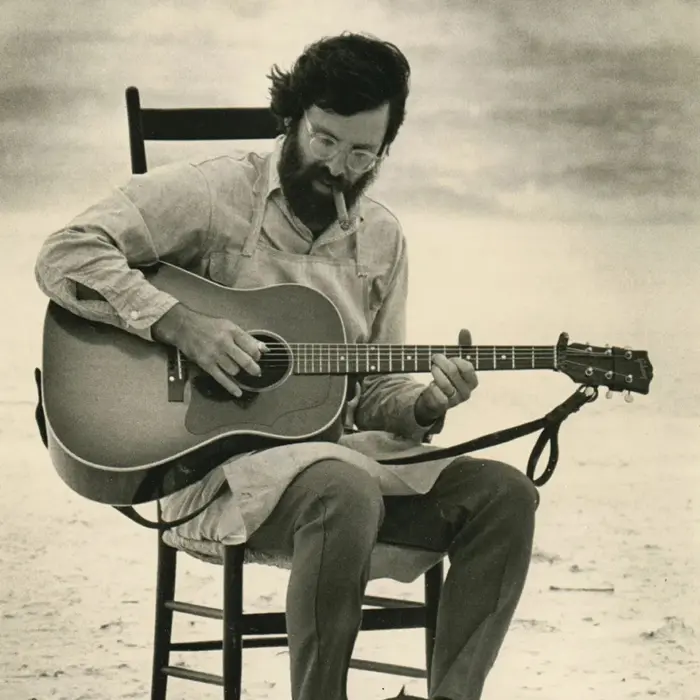

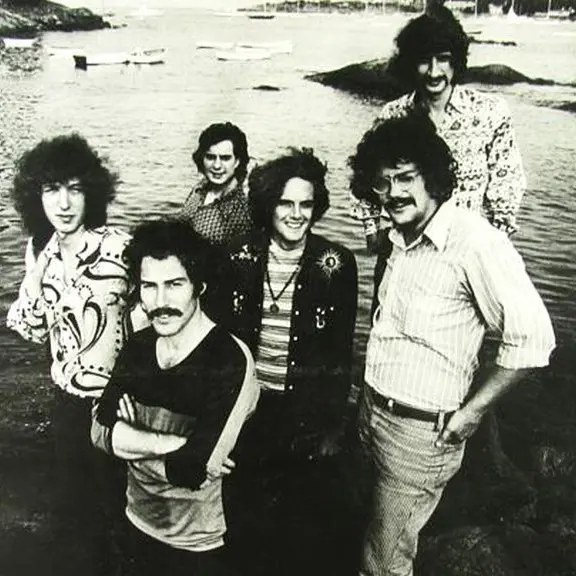

By the end of February 1963, he’d assembled the first incarnation of the group he’d lead for the next five years – guitarist-vocalist Geoff Muldaur, vocalist-harmonicist-banjoist Bruno Wolf and two members of The Charles River Valley Boys, steel guitarist-banjoist-mandolinist Bob Siggins and washtub bassist-jug player Fritz Richmond – and signed a deal with Vanguard.

UNBLUSHING BRASSINESS

The immediate result was Unblushing Brassiness, a 14-track collection released in March 1963 that critic Ronnie D. Lankford Jr. called “a quantum leap for folk music,” noting that it combined the pretty, pop-folk of The Kingston Trio with the gritty, tradition-centric songs of Dave Van Ronk.

And that summation seems perfectly in line with Kweskin’s own take on the group since, as he told music historian Nat Hentoff, he never considered the band to be “revivalists” but rather a blend of varied elements. “We not only have no one ‘tradition’ to try to be faithful to,” he said, “but for much of what we play, we don’t know if we even have tradition to be concerned with. We can do almost anything we want.”

MEL LYMAN, NEW YORK CITY DEBUT, NEW YORK TIMES REVIEW

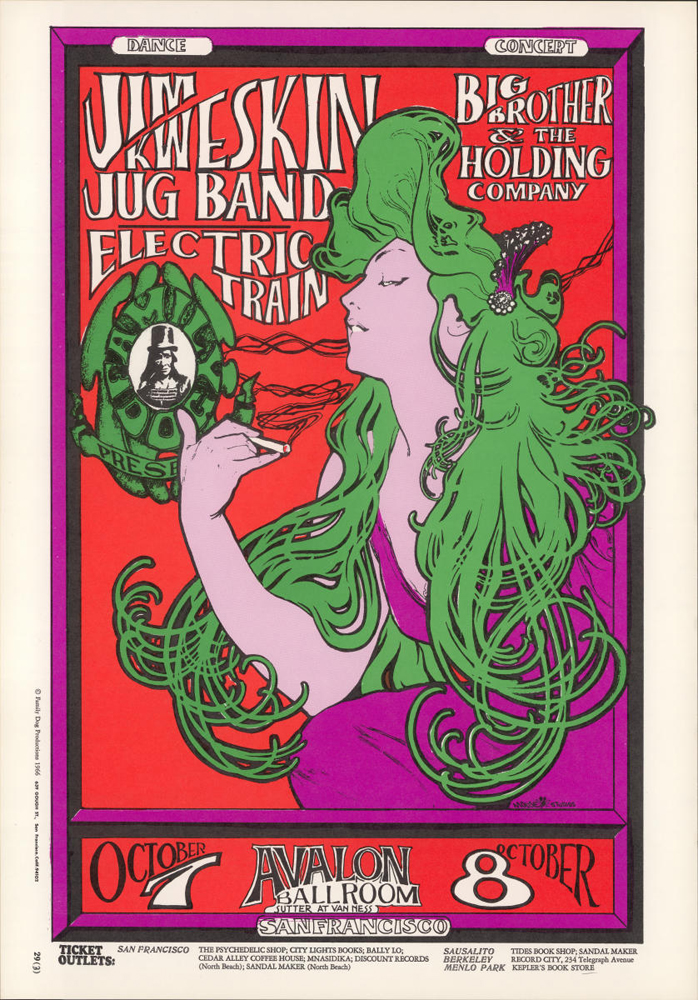

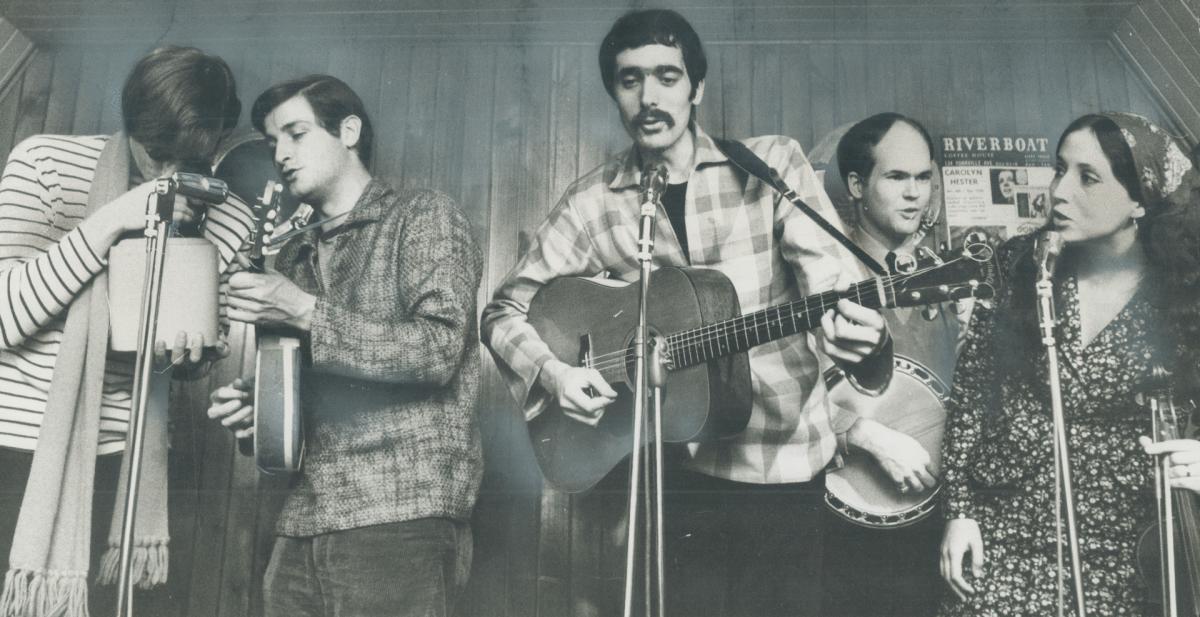

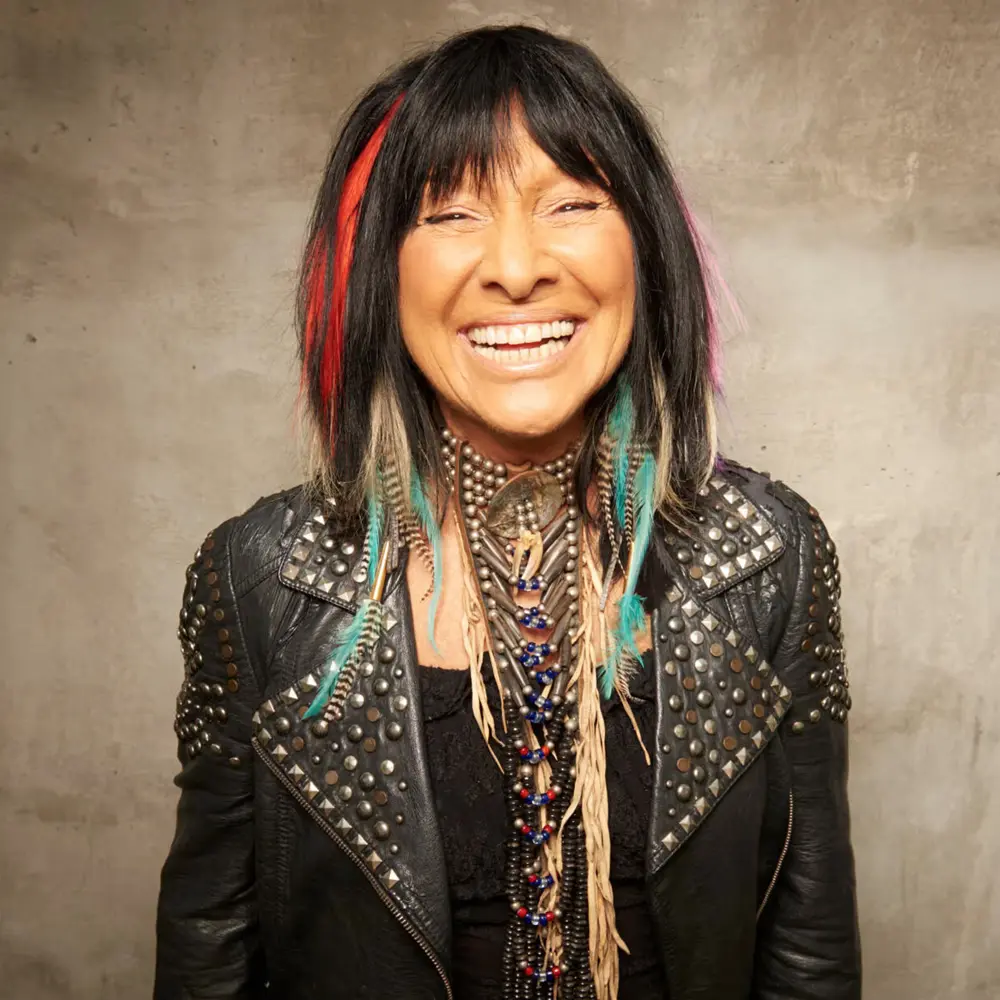

In September 1963, after Mel Lyman replaced Siggins and the group had made multiple appearances in and around Boston/Cambridge, Kweskin and The Jug Band made their New York debut at The Bitter End. Robert Shelton of The New York Times wrote a rave review headlined “Kweskin Quintet at Bitter End Puts Polish in the Ragtime Jug” and in late September the band appeared at the Hootenanny at Carnegie Hall with Pete Seeger, Phil Ochs, Buffy Sainte-Marie and others.

SYMPHONY HALL, NEWPORT FOLK FESTIVAL, TV APPEARANCES

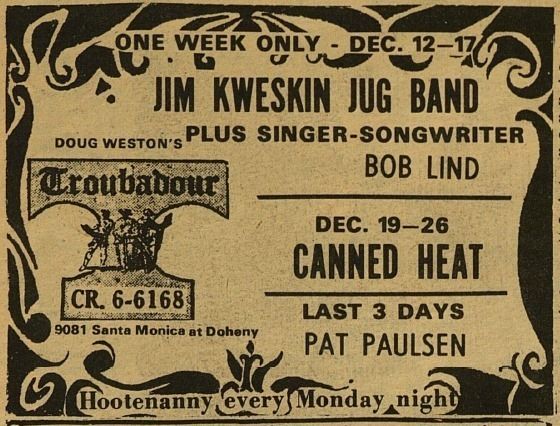

In November 1963, Kweskin and The Jug Band debuted at Symphony Hall in Boston (with opener Jackie Washington), followed in 1964 by regular shows at Club 47, The Unicorn Coffee House and King’s Rook in Ipswich (renamed Stonehenge Club in 1969). They appeared on The Steve Allen Show and The Tonight Show – with host Johnny Carson, an accomplished drummer, sitting in on kazoo – and debuted at the Newport Folk Festival, where they also appeared in 1965, ’66 and ’67.

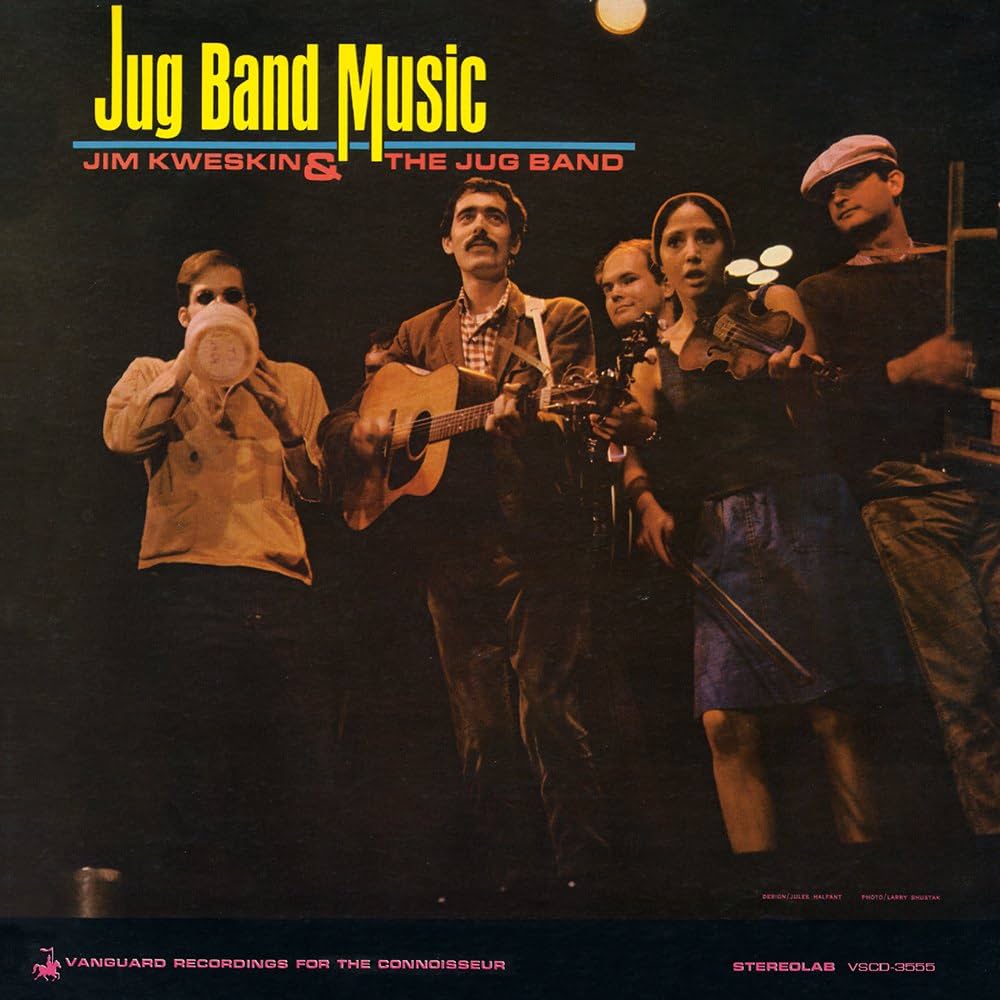

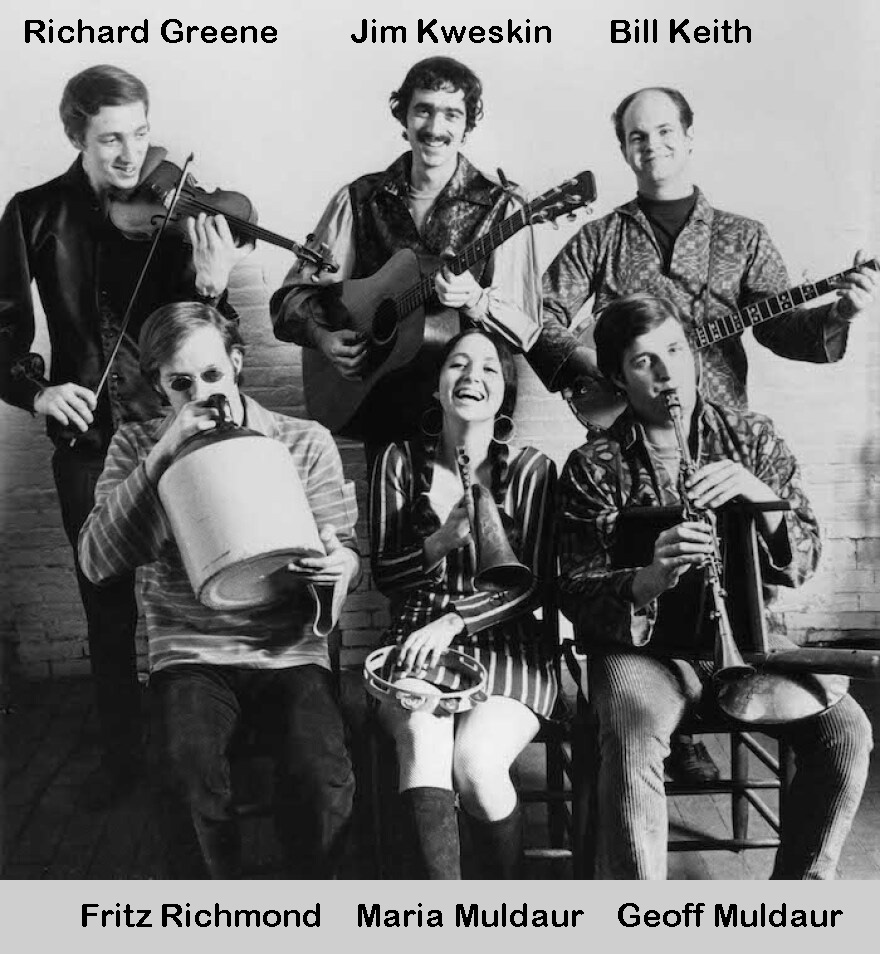

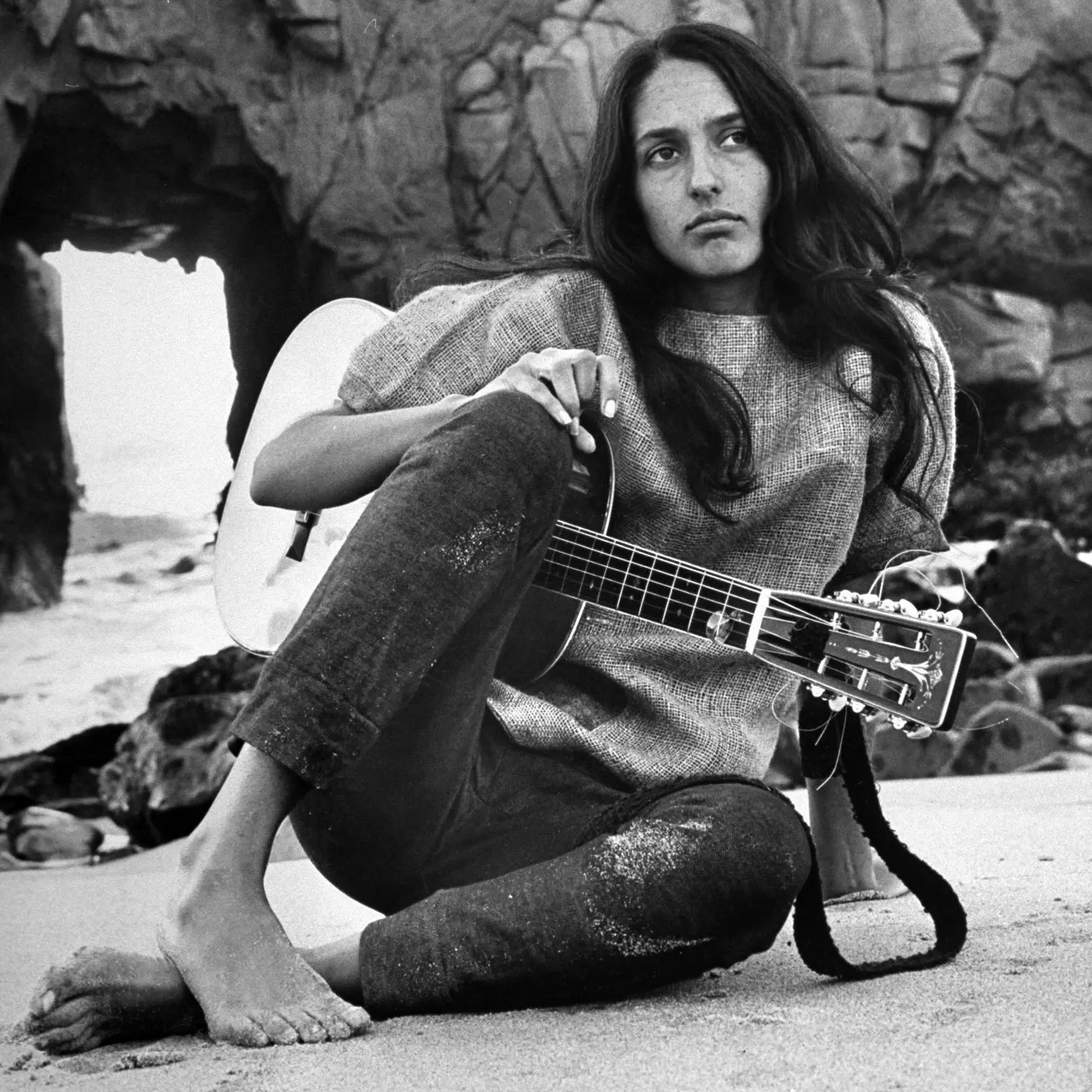

MARIA D’AMATO, BILL KEITH, JUG BAND MUSIC

By 1965, the band had grown into a septet with the additions of vocalist-fiddler Maria D’Amato (later Maria Muldaur), previously of the New York-based Even Dozen Jug Band, and five-string banjoist Bill Keith, a Bostonian who’d spent two years with Bill Monroe’s Bluegrass Boys. Vanguard released their second LP, Jug Band Music, featuring crowd favorites “Blues My Naughty Sweetie Gives to Me” and “Rag Mama” and D’Amato’s ripping rendition of the Leiber/Stoller-penned “I’m a Woman” plus covers of Chuck Berry’s “Memphis” and – as the LP’s title indicates – Will Shade’s Memphis Jug Band’s “Jug Band Music.”

RELAX YOUR MIND, SEE REVERSE SIDE FOR TITLE, RICHARD GREENE

In 1966, after Vanguard issued Kweskin’s solo album Relax Your Mind (recorded at Club 47 with Lyman and Richmond), the label released the band’s third album, See Reverse Side for Title, which received mixed reviews. After touring nationwide for much of the year and returning to Symphony Hall in December, The Jug Band added fiddle player Richard Greene, previously of Bill Monroe’s Bluegrass Boys.

REPRISE SIGNING, GARDEN OF JOY, DISBANDING, COMPILATIONS

In late 1966, the group left Vanguard for Reprise to make their fourth and final album, Garden of Joy, released in 1967. The LP featured 11 wildly varied songs, from Lead Belly’s “When I Was a Cowboy” to a jugged-up rendition of the Ellington-Bigard-Mills jazz classic “Mood Indigo.”

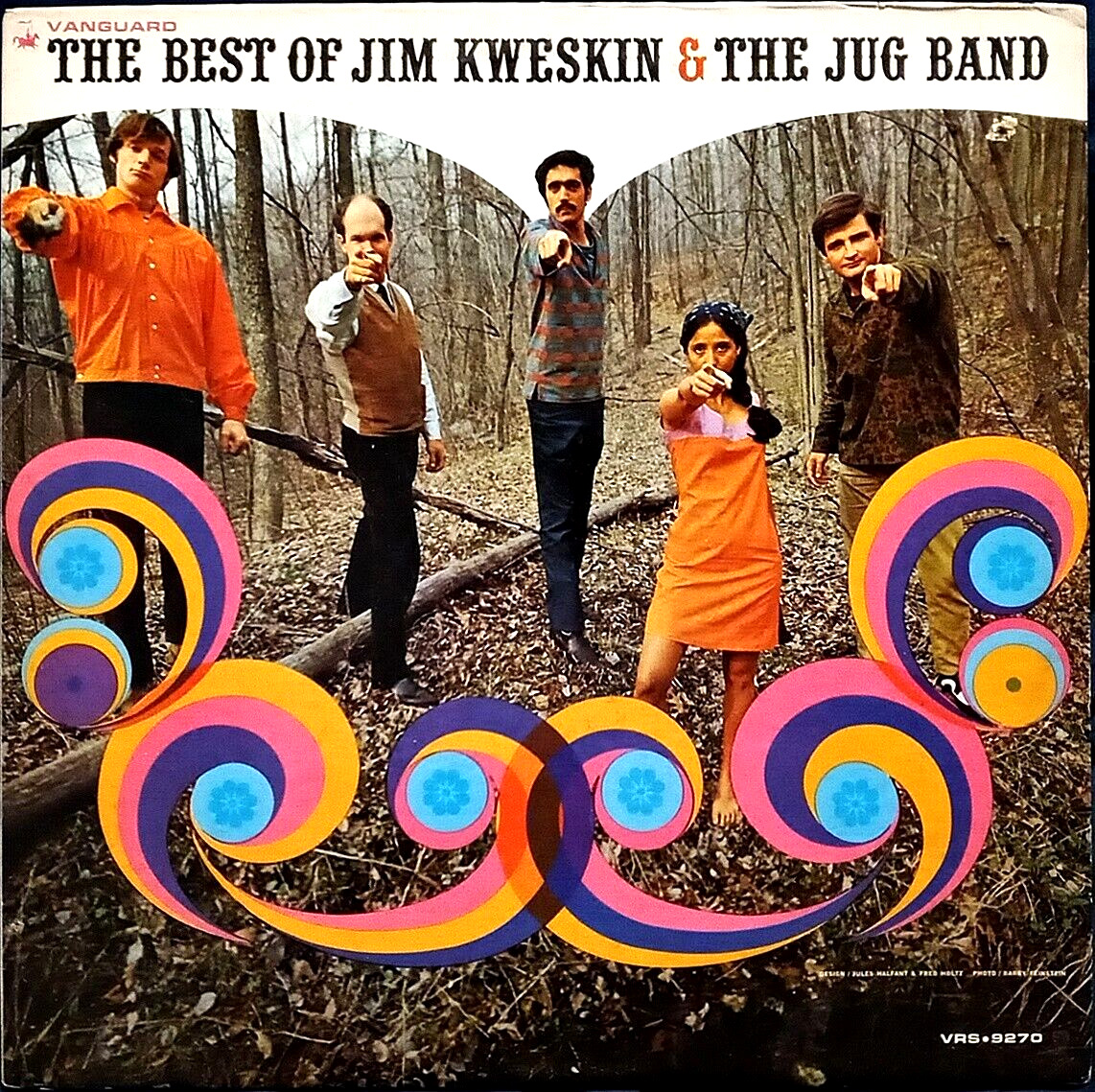

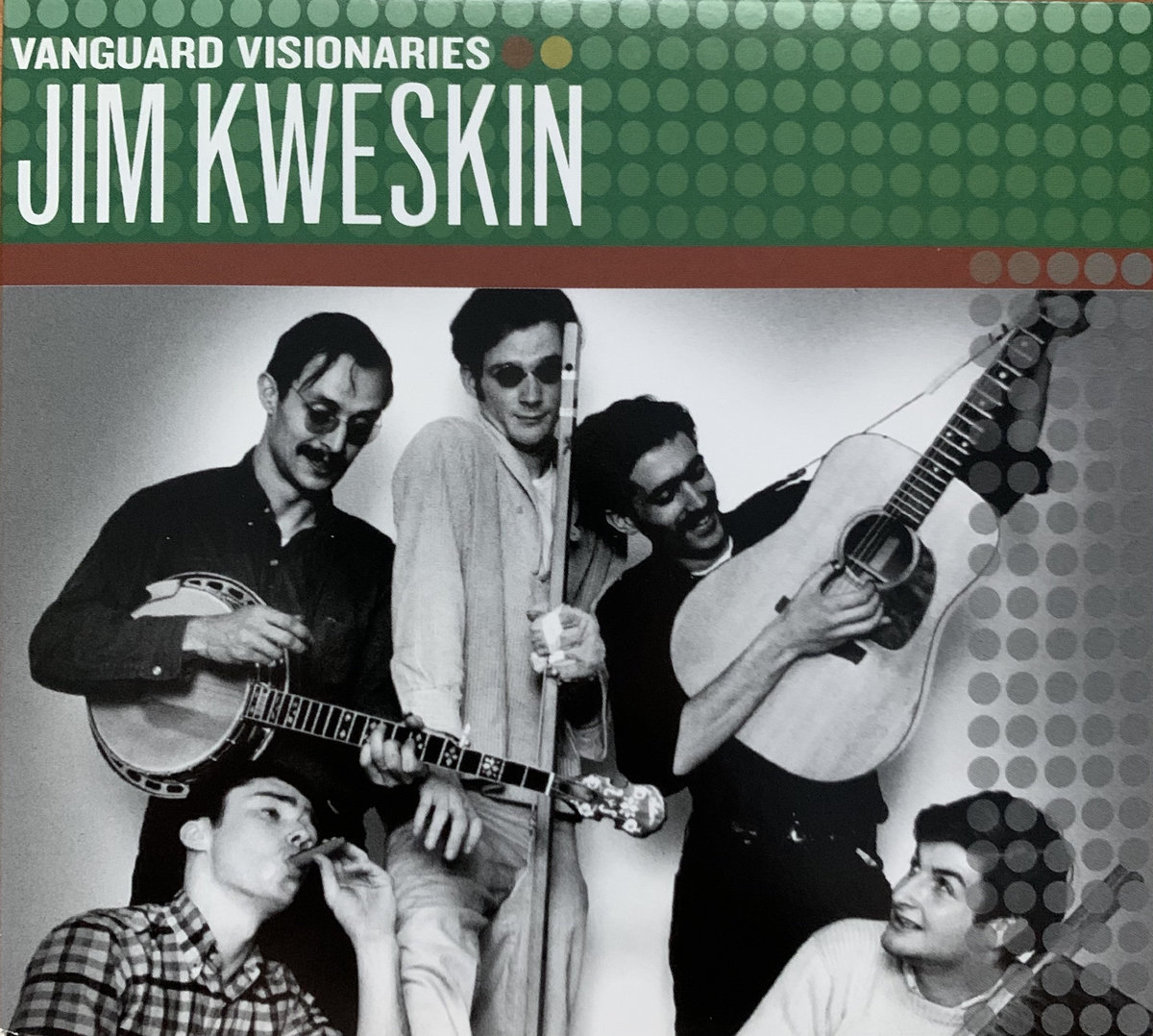

After it hit the shelves, the band played mostly at Café au Go-Go in New York and Club 47; after a six-night stand at the Go-Go in March 1968, they made a few more appearances and broke up. The group’s material has been included on a number of compilations including three from Vanguard:, Greatest Hits! (1970), Acoustic Swing & Jug (1998) and Jim Kweskin: Vanguard Visionaries (2007).

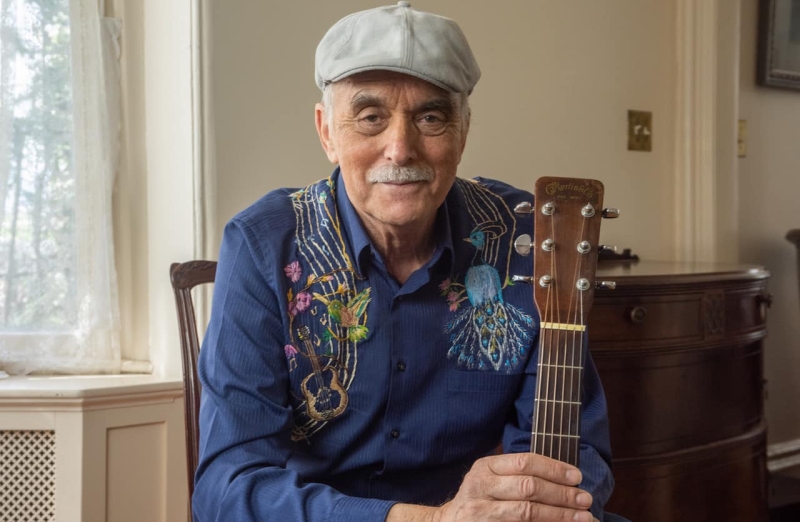

POST-JUG BAND ACTIVITY

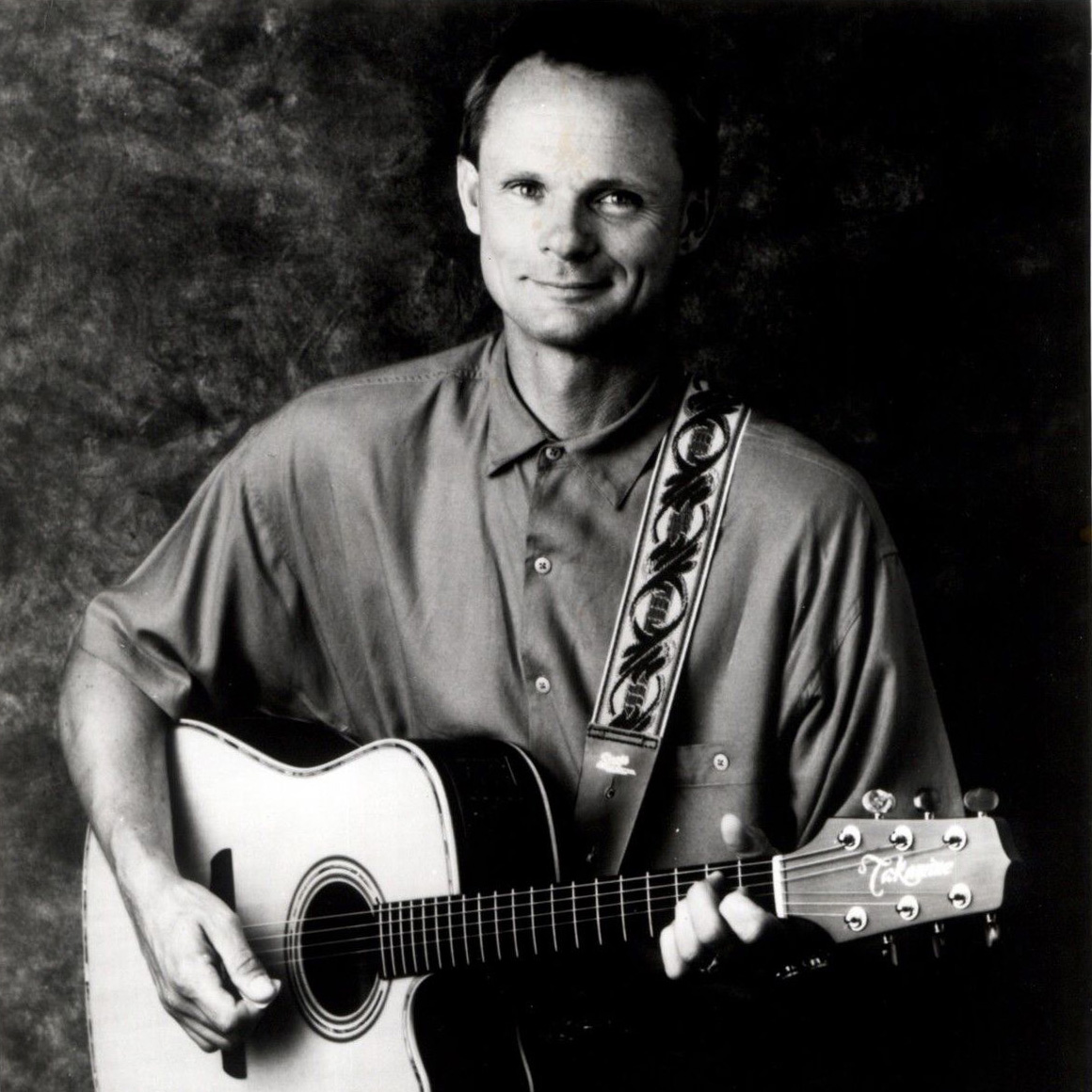

Since the band’s split, Kweskin has recorded 14 albums including 2015’s Penny’s Farm with Geoff Muldaur, 2020’s I Just Want To Be Horizontal with Samoa Wilson and 2024’s Never Too Late: Duets with My Friends. Geoff Muldaur has recorded 12 solo albums, his most recent being 2009’s Texas Sheiks, and Maria Muldaur – whose “Midnight at the Oasis” reached #6 in 1973 – has recorded 38 albums since 1974, her most recent being 2021’s Let’s Get Happy Together.

Richard Greene joined Seatrain and Muleskinner, formed The Greene String Trio and has been a session player since the late ‘60s, working on dozens of LPs with artists as diverse as James Taylor, Rod Stewart and Herbie Hancock. Bob Siggins became a neuroscientist while continuing to perform and continues to play gigs regularly with the San Diego-based bands Cheeky Monkey and Bonehead.

Richmond became a successful session musician and recording engineer until he passed away in 2005 at age 66 and Keith played with Jonathan Edwards, Jim Rooney and a laundry list of others before his death in 2015 at age 75, three weeks after his induction into the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame. Lyman ran the Fort Hill Community in Roxbury until his death in 1978 at age 40.

GEOFF MULDAUR COMMENTS ON KWESKIN PARTNERSHIP, FUTURE

At a 2005 memorial concert for Richmond, Muldaur talked about his decades-long partnership with Kweskin. “There’s this wonderful old music – traditional folk music, mostly American – that we want to keep alive,” he said. “We want to pass it on to future generations so that it keeps going. That’s what we were doing back when we were young, and we’re still doing it.”

Asked at the same concert whether he thinks future generations will continue passing traditional music along, 79-year old Muldaur said he’s highly doubtful because he doesn’t see many young faces in his audiences these days. “I play for old people,” he laughed. “And their parents.”

(by D.S. Monahan)