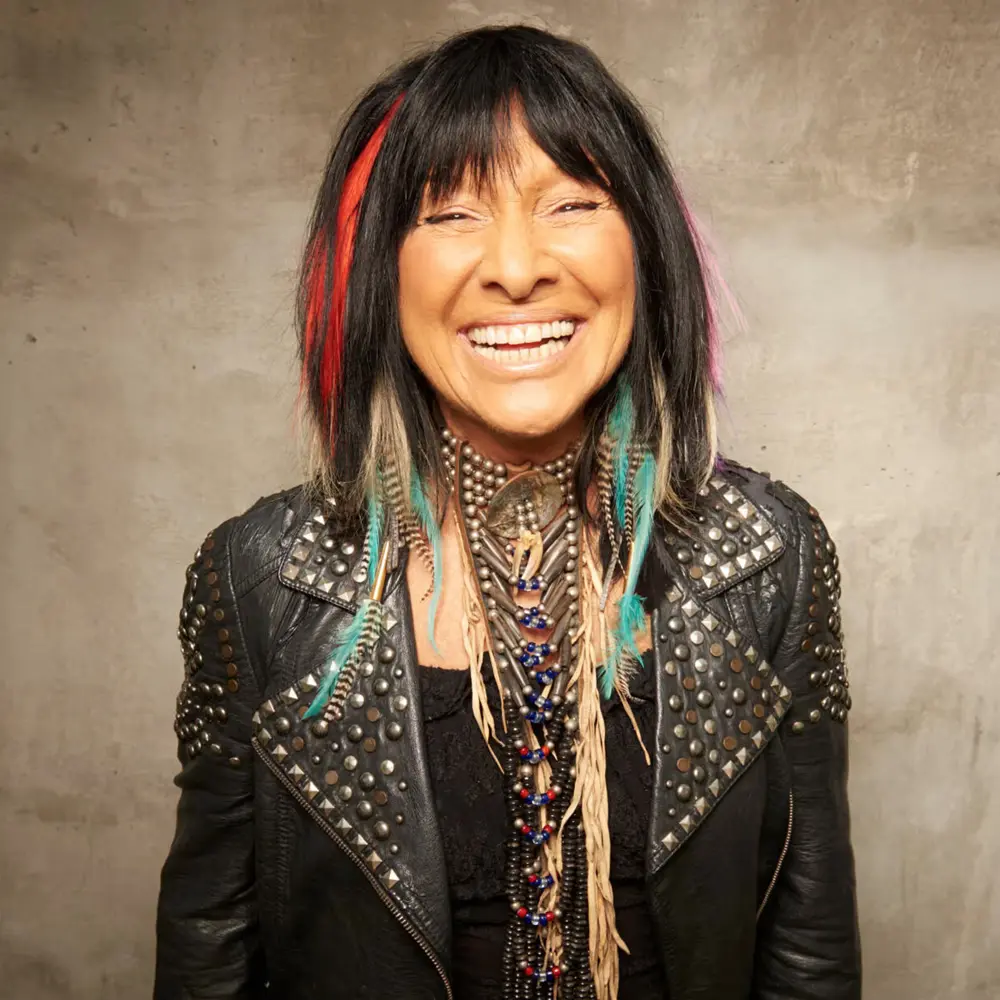

Buffy Sainte-Marie

After spending her lifetime being ahead of her time, Buffy Sainte-Marie is arguably the most oxymoronic figure in the history of popular music, indisputably iconic yet often overlooked, even ignored. “Her omission from the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame is galling,” wrote Andrea Warner, her official biographer, in The Globe and Mail in 2021, and it’s difficult – millions would say impossible – to disagree.

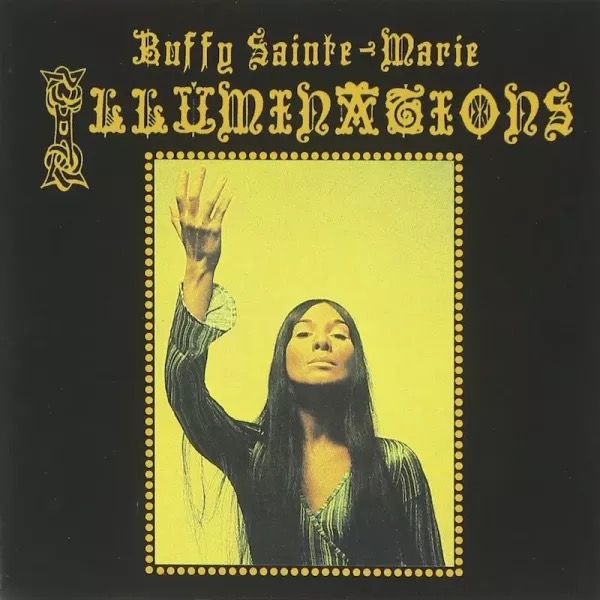

In equal measure a singer, songwriter, musician, educator, activist and visual artist, Sainte-Marie’s extensive achievements include winning Billboard’s Best New Artist award (1964); being the first singer to record a quadraphonic album (Illuminations, 1969); winning an Academy, Golden Globe and BAFTA Award (for “Up Where We Belong,” 1983); being the first person to receive an honorary doctorate from the University of Massachusetts (1983); being the first recording artist to deliver an entire album using file-sharing software (Coincidences and Likely Stories, 1991); and being the first septuagenarian to receive the Polaris Music Prize (for Power in the Blood, 2015).

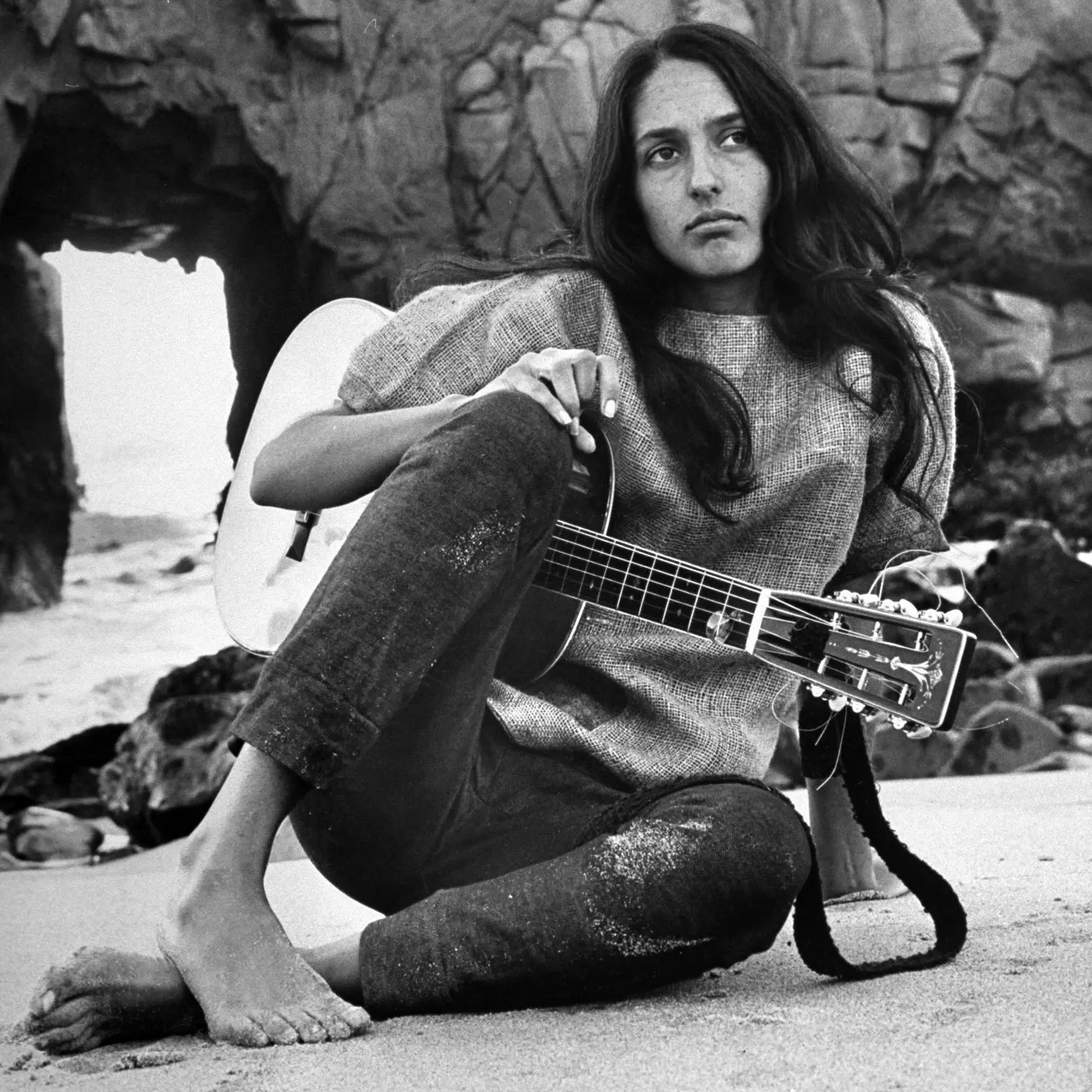

Known as much for her political engagement as for her superb songwriting, unique melodic approach and compelling vocal style, Sainte-Marie’s tireless championing of Indigenous people’s rights over the past six decades is at least as impressive as her musical legacy. As Herbert Kupferberg wrote in The Boston Globe in 1970 – using language many modern ears would deem unsuitable for publication – “the best-known fighter for the American Indian since Geronimo is a spunky, sexy, 100-pound girl named Buffy Sainte-Marie” and as NPR music critic Ann Powers wrote in 2015 – using language considered more appropriate in the 21st century – she’s “more Bjork than Baez, more Kate Bush than Laurel Canyon…a risk-taker, always chasing new sounds, and a plain talker when it comes to love and politics.”

As for music, Sainte-Marie has recorded 16 studio albums with consistent lyrical themes of love, war, religion and mysticism and her best-known song, “Universal Soldier” (written in 1963), has inspired 157 cover versions, according to a feature in The Guardian in November 2022, by singers as diverse as Elvis Presley, Donovan, Janis Joplin, Barbara Streisand, Glen Campbell, Courtney Love and Neko Case.

EARLY YEARS, ANCESTRY/ADOPTION CONTROVERSY

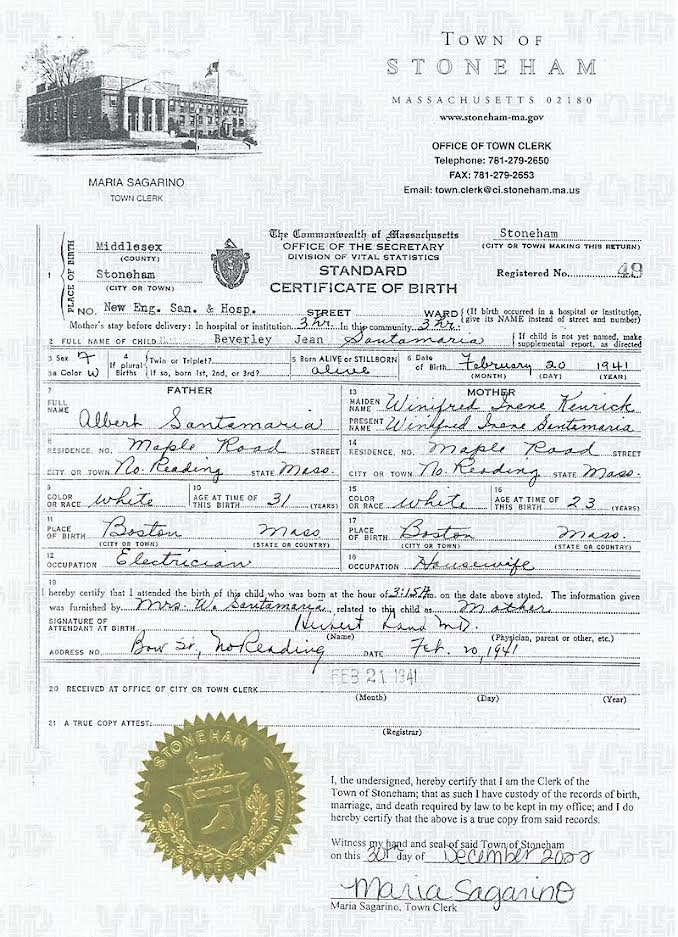

Throughout her career, Sainte-Marie has said that she was born on an Indian reserve in Canada – the biography on her official website says it was Piapot (Cree) Indian Reserve No. 75 in Saskatchewan – and adopted before the age of two following the deaths of her parents, as noted in the book A to Z of American Indian Women (Facts on File, 2008). She’s said repeatedly that all records of her biological parents were sealed, that she’s never known her exact date of birth – including the year (though she’s said she thinks it was 1941 or 1942) – and that Albert and Winifred Santamaria of Wakefield, Massachusetts, adopted her and named her Beverley Jean.

Her decades-long claims of having Indigenous ancestry and being adopted came into question in October 2023, however, when CBC News published a birth certificate showing that Sainte-Marie was born Beverley Jean Santamaria at New England Sanitarium and Hospital (now Boston Regional Medical Center) in Stoneham, Massachusetts, on February 20, 1941, to Albert and Winifred Irene Santamaria, making them her birth parents, not her adoptive ones. Hospital records note that the Santamarias were “otherwise known” by an abbreviated last name, Ste. Marie, and the birth certificate – which lists Albert, Winifred and Beverley Jean as “white” in the “Color or Race” section – was authenticated by Stoneham Town Clerk Maria Sagarino in December 2022.

Also in October 2023, as part of their investigative series The Fifth Estate, CBC Television ran an hour-long exposé which concluded that Sainte-Marie’s assertions about her ethnicity and adoption are patently false. She denied the allegations that she’s a pretendian, calling herself “a proud member of the Native community with deep roots in Canada” and insisting that she’s never known her biological parents. “I don’t know where I’m from or who my birth parents were, and I will never know,” she said in a written statement. “To those who question my truth, I say with love, I know who I am.”

Winifred Santamaria (née Kenrick), an editor at Houghton Mifflin in Boston, was of English ancestry and claimed to be part Mi’kmaq, Albert Santamaria was Italian-American and Sainte-Marie told The Guardian in November 2022 that her family was “more The Sopranos than Dances with Wolves.” She completed her K-12 education in Wakefield and spent most summers in Maine.

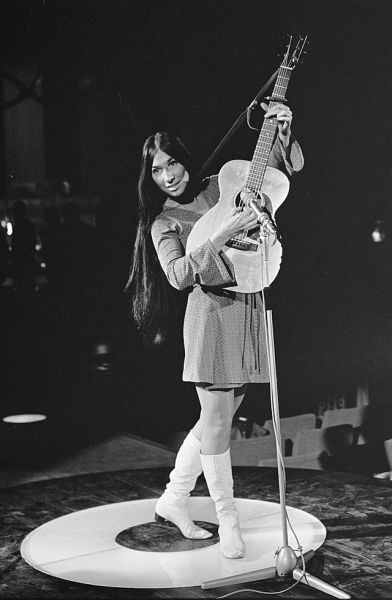

MUSICAL BEGINNINGS, EARLY PERFORMANCES

At age three, Sainte-Marie, started teaching herself how to play piano. “And when I say that ‘I taught myself how to ‘play,’ I’m not kidding because to me it really was play,” she said in 2015. “And to this day it’s play and that’s why it’s still good.” By age four, she was writing poems and putting them to music.

At age 16, by then nicknamed “Buffy,” she taught herself guitar and ultimately found 32 different ways to tune the instrument, she’s said, part of her lifelong draw to constant musical experimentation. “As a little kid, I banged on pots and pans, I’d play with rubber bands, I’d blow on grass, I played the mouth bow,” she said in an interview with Vogue. “Later, I was using a Synclavier and a Fairlight, which were the earliest standing music computers.”

In 1958, Sainte-Marie enrolled at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, two years before Taj Mahal did the same. “She had a great fan base there at the university,” Mahal said in 2006. “And wherever she was gonna play, man, we were there.” Using an elongated, hyphenated version of the Santamaria family ’s abbreviated last name – “Sainte-Marie” instead of “Ste. Marie” – she appeared at the university’s Bowker Auditorium, the Saladin Tea House in Amherst and other small venues while majoring in Eastern philosophy and education, graduating in 1962 with a GPA that put her among the top 10 students in her class.

With no intention of becoming a professional musician, she planned to continue her studies in India and eventually become a teacher, but first she headed to Boston where, in the fall of 1962, began playing at folk venues like Café Yana and Someplace Else. In 1963, she started gigging at venues including The Second Fret in Philadelphia, San Remo Coffee House in Schenectady and Toronto’s Purple Onion Coffee House, where she wrote “Universal Soldier” that year as a protest against the rapidly escalating Vietnam War.

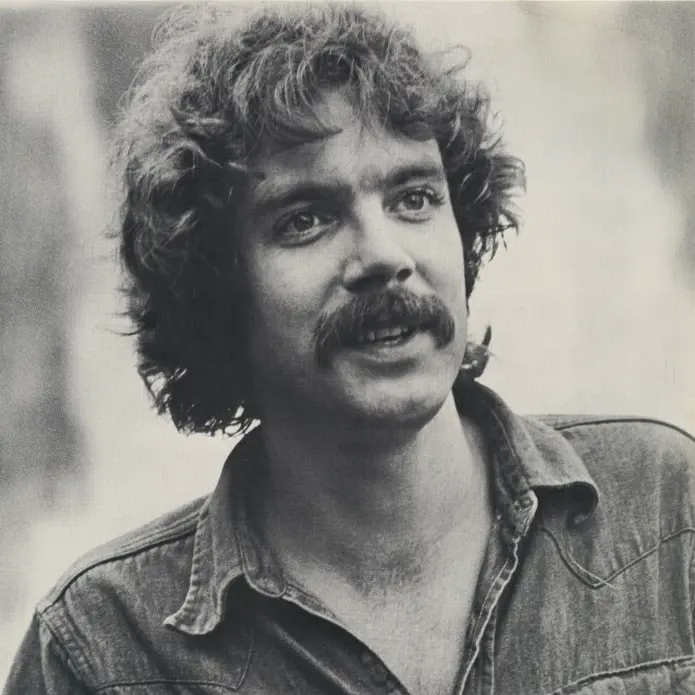

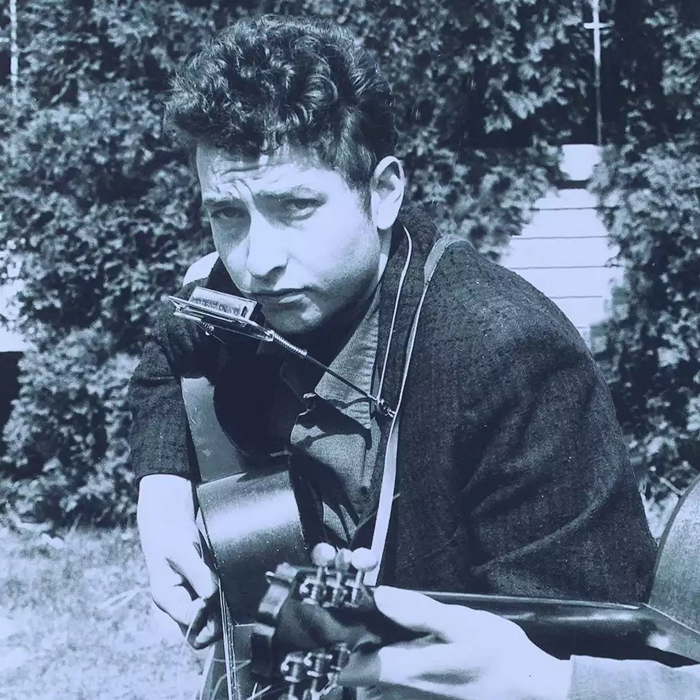

MOVE TO GREENWICH VILLAGE, VANGUARD SIGNING, DEBUT ALBUM

In early 1964, Sainte-Marie relocated to Greenwich Village, staying at the YWCA on 14th Street. Within a few days of arrival, she appeared at Gerde’s Folk City and 22-year old Bob Dylan was in the audience. “He heard me play, he liked it and he said, ‘Go see Sam [Hood, owner of The Gaslight Café]’ and within a week or two [New York Times music critic] Robert Shelton came to see me play and wrote a glowing review,” Sainte-Marie said in 2006. Hood posted an oversized copy of the review – headlined “Old Music Taking on New Color: An Indian Girl Sings Her Compositions and Folk Songs” – at the Gaslight’s front entrance, and Vanguard Records signed Sainte-Marie less than two weeks later.

In April 1964, her debut album, It’s My Way!, hit the shelves. A 13-song collection including 11 originals that critic William Ruhlman called “one of the most scathing topical folk albums ever made,” it established Sainte-Marie as the first female on the burgeoning singer-songwriter scene, years ahead debut albums by Janis Ian (1967), Laura Nyro (1967), Joni Mitchell (1968) and Carole King (1970). “I didn’t know I was ahead of the pack at the time because I didn’t know there was going to be a pack,” she told The Guardian in 2022.

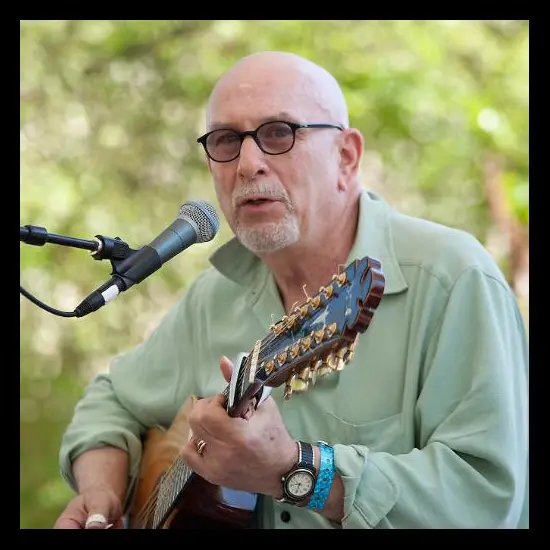

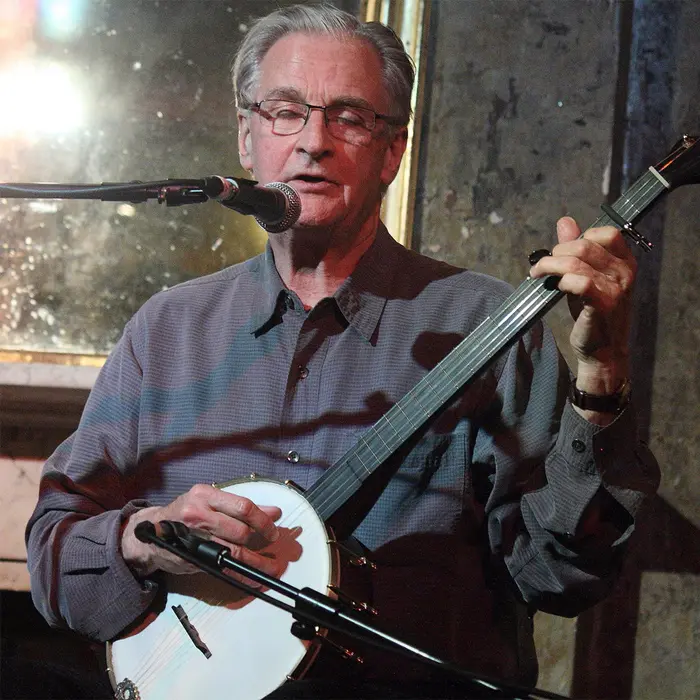

GROWING POPULARITY, CLUB 47 DEBUT, CREE FAMILY ADOPTION

In mid-1964, propelled by the popularity of songs like “Universal Soldier,” “Cod’ine” and “Now That the Buffalo’s Gone,” Sainte-Marie began headlining at clubs across North America. In September that year, after she appeared at Wakefield Memorial High School (her alma mater) in June, she debuted at Club 47 in Cambridge, where The Charles River Valley Boys, Jim Kweskin & The Jug Band, Geoff and Maria Muldaur, Mitch Greenhill, Tom Rush, Eric von Schmidt and Taj Mahal also appeared that month.

Later in 1964, Sainte-Marie traveled to Saskatchewan and, according to tribal custom, was adopted by a Cree family that said they were related to her biological parents. Following the CBC claim in 2023 that she was actually born to white parents in Massachusetts, the acting chief of Piapot First Nation, Ira Lavallee, said his community will continue to accept her as one of their own. “I can relate to and understand a lot of our people who feel betrayed and in a sense lied to by her claiming Indigenous ancestry, when in fact she may not be Indigenous,” he told CBC News. “We do have one of our families in our community that did adopt her. Regardless of her ancestry, that adoption in our culture to us is legitimate.”

MANY A MILE, NEWPORT FOLK FESTIVAL DEBUT, OTHER ‘60S ALBUMS

In 1965, between appearances on American Bandstand, Soul Train, The Johnny Cash Show and The Tonight Show, Sainte-Marie recorded her second LP for Vanguard, Many a Mile, which included “Until It’s Time For You To Go” – covered by Bobby Darin, Roberta Flack, Elvis Presley, Barbara Streisand, Neil Diamond, Sonny & Cher, Bette Davis and others – and in 1966 she debuted at the Newport Folk Festival.

Vanguard issued four more of her albums before the end of the ‘60s, Little Wheel Spin and Spin (1966), Fire & Fleet & Candlelight (1967), I’m Gonna Be a Country Girl Again (1968) and Illuminations (1969), the last of which was hailed as a creative tour de force – it was recorded in quadrophonic using a Buchla synthesizer – but was a commercial nonevent.

1970S ALBUMS, SESAME STREET

The first half of the 1970s was relentlessly busy for Sainte-Marie, who played shows from Toronto to Tokyo. She recorded three more LPs for Vanguard, She Used to Wanna Be a Ballerina (1971), Moonshot (1972) and Quiet Places (1973), two albums for MCA, Buffy (1974) – which outsold all of her Vanguard albums combined – and Changing Woman (1975) and one disc for ABC Sweet America (1976). From 1975-1980, Sainte-Marie made regular appearances on the children’s program Sesame Street and in a 1977 episode she became the first person to breastfeed on American television.

“UP WHERE WE BELONG,” BLACKLISTING

In the 1980s, Sainte-Marie stayed comparatively out of the limelight musically with the exception of co-writing (with then-husband Jack Nitzsche) “Up Where We Belong” for the film An Officer and a Gentleman. The tune won an Academy Award, a Golden Globe Award and a BAFTA Award for Best Original Song. Sainte-Marie has said that in the ‘80s she learned that she’d been blacklisted by the US government going as far back as the mid-1960s. “[1963-68 US President Lyndon B. Johnson] had been writing letters on White House stationery praising radio stations for suppressing my music,” she explained in a 1999 interview.

COINCIDENCES AND LIKELY STORIES, RECENT ALBUMS

In mid-1991, she recorded Coincidences and Likely Stories, her first album in 16 years, issued in January 1992 by Ensign/Chrysalis/EMI. In 1995, Sainte-Marie was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame, in 1997 she was awarded the Order of Canada and in 1998 she received a star on Canada’s Walk of Fame in Toronto. In February 2025, the Canadian government stripped her of the Order of Canada, citing reports that she had fabricated her Indigenous ancestry. The decision was “based on evidence and guided by the principle of fairness,” according to the government’s official online publication, Canada Gazette.

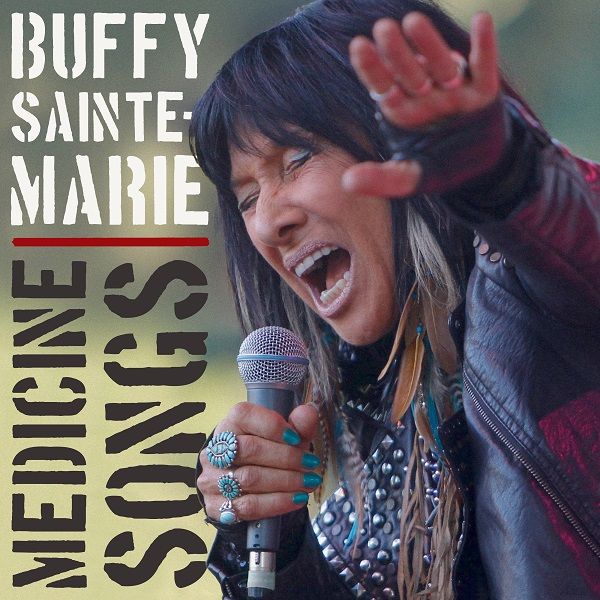

In September 2008, after Sainte-Marie took another 16-year hiatus to focus on educational projects, activism and her visual art, Gypsy Boy Music issued her 14th album, Running for the Drum, followed by True North releasing her most recent LPs, Power in the Blood (2015) – which won Canada’s Polaris Music Prize – and Medicine Songs (2017). In March 2025, after Sainte-Marie confirmed to national news agency The Canadian Press that she’s a US citizen, not a Canadian citizen or a permanent legal resident of Canada, the organizations that award the Polaris Prize and the Juno Awards revoked all honors that they’ve bestowed on her over the decades. Both organizations require that honorees be Canadian citizens or permanent legal residents of Canada.

CARRY IT ON DOCUMENTARY

In September 2022, the 90-minute documentary Buffy Sainte-Marie: Carry It On premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival. An in-depth review of her life and career both as artist and activist, it includes interviews with singer-songwriters Robbie Robertson, Joni Mitchell and Jackson Browne, Steppenwolf frontman John Kay, broadcaster George Stroumboulopoulos and Andrea Warner, author of Buffy Sainte-Marie: The Authorized Biography (Greystone Books, 2018).

Speaking with Point of View magazine upon the film’s release, director Madison Thomas cited Sainte-Marie’s remarkably forward-thinking vision throughout the decades. “Buffy is 50 years ahead of us. Hands down,” she said. “It’s across the board in every facet of her life. It’s not too late for the rest of us to catch up and I think a good start is hearing her story and listening to her music and message.”

(by D.S. Monahan)