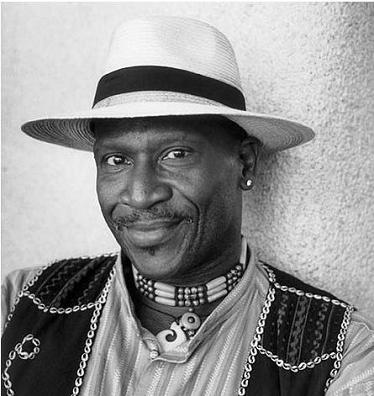

Taj Mahal

The Taj Mahal is “one of the universally admired masterpieces of the world’s heritage,” according to the United Nations. But for musicians and music lovers across New England and around the globe, Taj Mahal is the stage name of a world-music master.

A multi-instrumentalist maverick decades before “world music” was recognized as a musical category, for over 60 years Mahal has honed his craft to a level of substance and sublimity achieved by precious few, with 30 studio and 14 live albums and appearances on 28 others by artists as diverse as Ry Cooder, Etta James, Van Morrison, Eric Clapton and Sammy Hagar. A genuinely global citizen, Taj has transcended cultural barriers with grace and aplomb using his forward-looking fusion of Delta Blues, Caribbean, African, Hawaiian, Indian and South-Pacific influences to create a cherished catalogue of songs that live deep in the hearts of millions across several generations.

MUSICAL BEGINNINGS

Born Henry St. Claire Fredericks Jr. in Harlem on May 17, 1942, Taj moved with his family to Springfield, Massachusetts, in the early 1950s – when it was the quintessential melting pot of people from the American South, Europe, the Caribbean, the Mediterranean and the Middle East – and he was exposed to a vast array of music. His father was an Afro-Caribbean jazz arranger and pianist who had worked with Ella Fitzgerald (who nicknamed him “The Genius”) and his mother was in a gospel choir: the family listened to music from around the globe on a shortwave radio.

Young Henry immersed himself in jazz at first, particularly Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk and Milt Jackson, then Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley and Little Richard, eventually developing a passion for African music. At age 11, he started piano lessons while teaching himself harmonica, trombone and clarinet, but he lost interest in piano at age 14 when he started taking guitar lessons with his new neighbor, Lynwood Perry, nephew of bluesman Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup. In 1959, Henry Jr. graduated from an agricultural vocational high school, where he sang with a doo-wop group and started playing banjo.

BECOMING “TAJ MAHAL,” EARLY APPEARANCES, RISING SONS

While in high school, Henry Jr. had all but decided to become a full-time farmer and he enrolled at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, majoring in animal husbandry and minoring in ethnomusicology. By the start of his junior year, however, he saw music as his future, adopted the stage name Taj Mahal – after a dream he had about Mahatma Gandhi’s spearheading of India’s independence – and formed an R&B group, Taj Mahal & The Elektras.

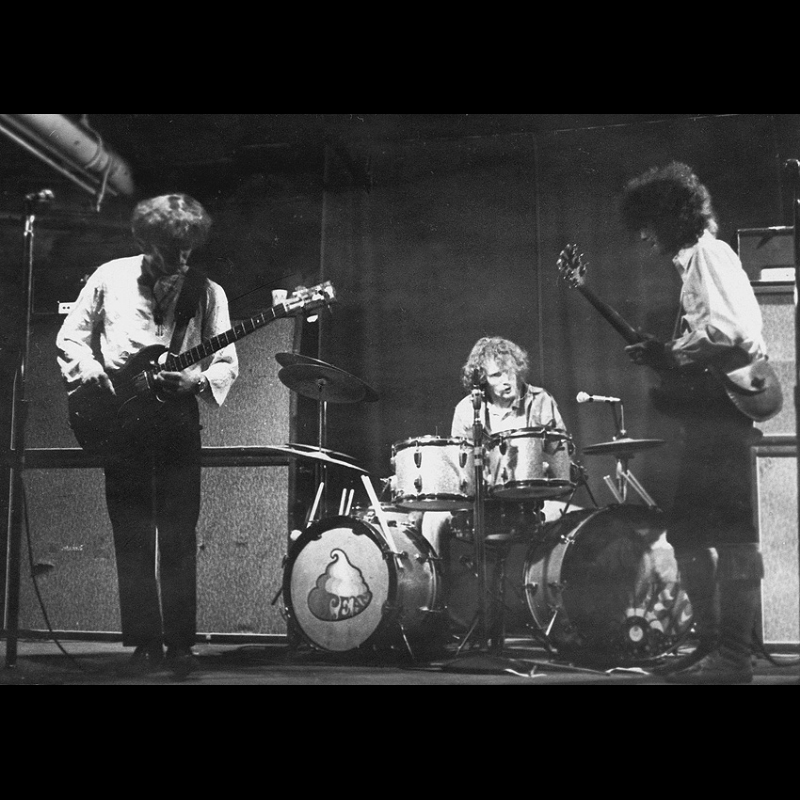

During his last two years at UMass, he performed in the school’s studio union and other small venues and after graduating in May 1964 he landed a regular gig at Club 47 in Cambridge, in addition to playing at Turk’s Head Coffeehouse and Charles Street Meeting House in Boston and King’s Rook in Ipswich. In 1965, Taj moved to Santa Monica and joined 17-year-old Ry Cooder in Rising Sons, one of era’s first interracial bands. The group signed with Columbia and opened for major acts including The Temptations and Otis Redding, but the label released only one single before Rising Sons disbanded in 1966. In 1992, Columbia issued the LP Rising Sons Featuring Taj Mahal and Ry Cooder, recorded over 25 years earlier.

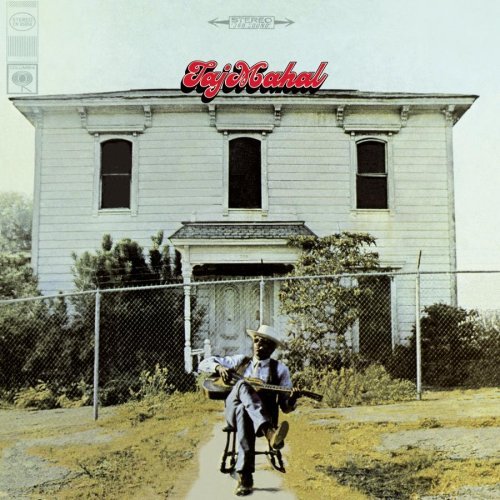

1960S, THE ROLLING STONES’ ROCK AND ROLL CIRCUS

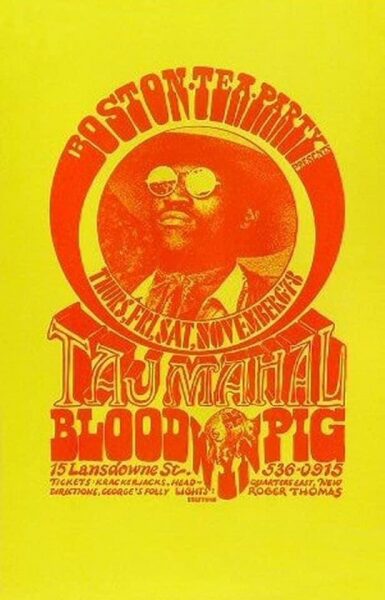

In 1966, Taj began doing regular solo shows at Jabberwock in Berkeley, and in 1967 he recorded his self-titled debut for Columbia, followed by The Nach’l Blues in 1968, when he debuted at the Unicorn Coffee House in Boston and the Newport Folk Festival. He appeared in The Rolling Stones’ Rock and Roll Circus, a film featuring the Stones, The Who and others but which was not released until 1996. In mid-1969, Taj recorded Giant Step / De Ole Folks at Home, a double album, and performed at several New England venues including The Boston Tea Party.

1970S, SOUNDER SOUNDTRACKS, 1980S, GRAMMY AWARDS

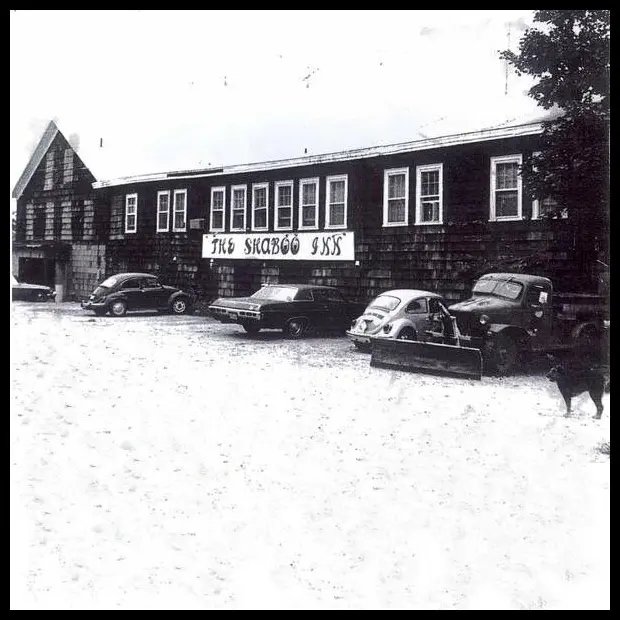

In 1972, Taj composed the score for Sounder, which won him a Grammy nomination, and in 1976 he scored the sequel, Part 2, Sounder. While touring worldwide throughout the 1970s, he played New England venues such as Concerts on the Common, the Orpheum Theatre and Paul’s Mall in Boston, Music Inn in Lenox and the Shaboo Inn in Connecticut. In 1976, Taj left Columbia for Warner Bros. Records and recorded three albums on the label over the next two years, during which time he appeared as the musical guest on Saturday Night Live (in October 1977). With disco ruling the charts and heavy-metal bands starting to dominate the market for live shows, however, Warner Bros. did not renew his contract when it ended in 1978 and he went without a record deal for a decade.

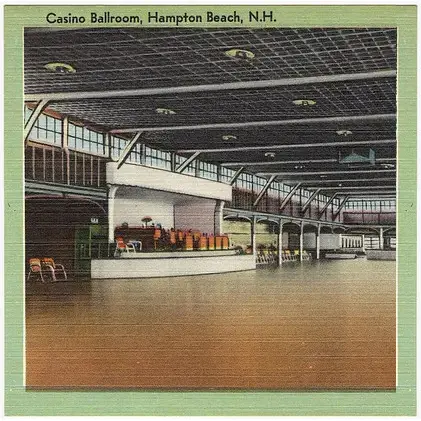

In 1981, Taj moved to Hawaii and kept a low offstage profile but maintained an exhausting concert schedule throughout the 1980s, appearing at festivals in the US, the UK, Canada, Europe and Australia. He returned to New England often to play venues including Jonathan Swift’s in Cambridge, Hampton Beach Club Casino and the Palace Theatre in New Haven.

In 1986, he recorded Taj – hailed as his “comeback album” – followed by 12 more LPs over the next 20 years, including Señor Blues (1997) and Shoutin’ in Key (2000), both of which won Grammys for Best Contemporary Blues Album. He won his third Grammy in 2007 for TajMo – a joint album with Keb’ Mo’ that featured a guest appearance by Bonnie Raitt – and a Grammy nomination for his 2008 release Maestro.

1990S, 2000S, CAREER REFLECTIONS

In 1995, the Water Lily Acoustics label released Taj’s most adventurous album, Mumtaz Mahal, on which he fused blues with traditional Indian instruments like the Mohan veena, a Hindustani classical guitar, and the chitravina, a fretless lute. In 1998, he contributed to the Americana album Largo, based on the music of Antonín Dvořák, along with Cyndi Lauper, Willie Nile, Joan Osborne, Rob Hyman, Garth Hudson, Levon Helm and The Chieftains.

In the 2000s, still recording and performing as much as ever – and playing his first show in Russia in 2013 – Taj received a number of prestigious awards: In 2006, he was named the official Blues Artist of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts; in 2009, he was induced into the Blues Hall of Fame; and in 2014, the Americana Music Association gave him a Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2017, he appeared at Carnegie Hall alongside a host of household names in a star-studded tribute to Aretha Franklin.

Asked in 2019 for reflections on his 60-plus years of songwriting, recording, performing and touring, Taj spoke about being a vessel through which music comes through, not a creator of that music per se. “I just want to be able to make the music that I’m hearing come to me – and that’s what I did,” he said. “When I say, ‘I did,’ I’m not coming from the ego. The music comes from somewhere else. You’re just the conduit it comes through. You’re there to receive the gift.”

(by D.S. Monahan)