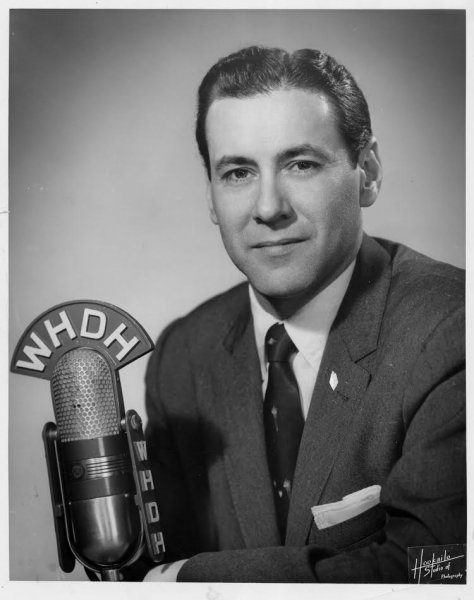

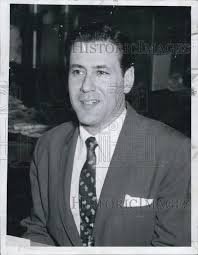

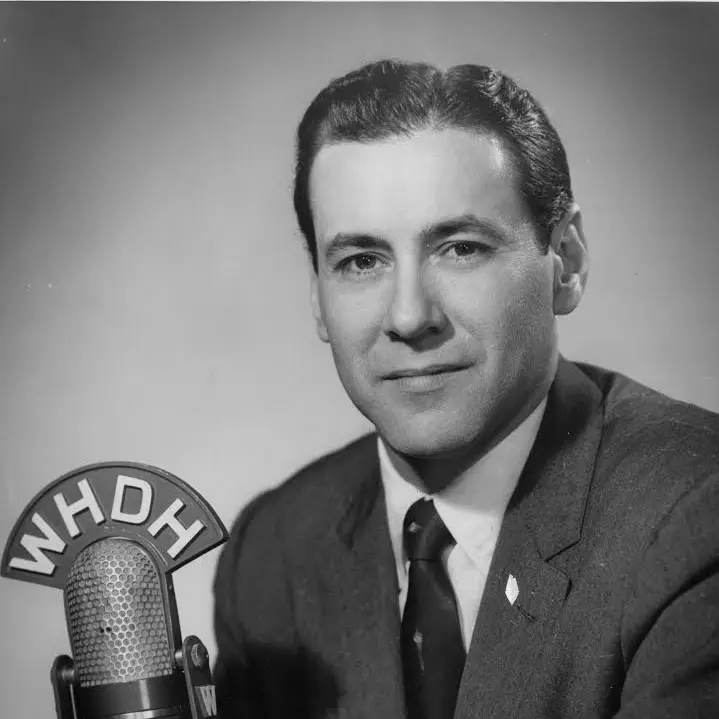

Bob Clayton

If you listened to Boston radio in the 1950s, then you knew exactly who Bob Clayton was. One of the most popular disc jockeys in town, virtually every teen loved listening to his Boston Ballroom show on WHDH at 850 on the AM radio dial.

Clayton was one of the original “personality deejays,” meaning he played the hits but also interviewed the top stars of the day and gave up-and-coming acts a chance to be heard. He also made loads of local appearances and his fans hoped and prayed that he’d come to their school to host a record hop. But Clayton had never planned on a career in broadcasting. In fact, his goal was to become a lawyer.

Early years

Clayton was born Robert Harry Klayman in 1914 and, like many Jewish Bostonians of his generation, he was raised in Dorchester, which was a predominantly Jewish neighborhood at the time. He graduated from Boston Latin School (like Arthur Fiedler and Leonard Bernstein), studied law at Northeastern University and graduated with his JD in 1936. After passing the bar exam, he joined a law firm in based in downtown Boston.

By then, he was married and eventually he and his wife had a son. But making a living was difficult for any new lawyer in the mid-‘30s; the Great Depression was at its peak and Boston already had an abundance of very well-established attorneys. When the US entered World War II following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, many men of his age enlisted or were drafted into the military, but not Clayton; he received a deferment because he had perforated ear drums, which prevented him from being sent overseas and left him stateside, still needing a better-paying job. And that’s when radio came calling.

WHDH, Becoming “Bob Clayton”

With tens of thousands of men going off to fight in Europe and the Asia-Pacific, suddenly there were openings at companies in a wide variety of fields, radio being one of them. Even though female announcers (even female engineers) picked up some of the slack, massive personnel shortages persisted. One night, Clayton heard an ad on the radio about a 12-week training course on how to be an announcer. Hoping to supplement his relatively meagre income, he completed the program and landed a job at WHDH in Boston in February 1943. He didn’t know if radio was for him or if he should go back to being an attorney, but he decided to give broadcasting a try and decide later.

The station’s management told him he should change his last name, which is not surprising given that “ethnic-sounding” names were frowned upon – even disparaged – in the ‘40s, ‘50s and much of the ‘60s. Announcers, movie stars, singers and other entertainers were regularly “invited” to choose a name that sounded more neutral, more so-called “American.” One very popular Boston announcer known as “Bill Marlowe” was actually Bill Moglia and, with that kind of switch in mind, Bob Klayman became “Bob Clayton.” (In the mid-1950s, one of the few announcers anywhere in the US to break with the custom and keep his actual name, even though it sounded “ethnic,” was WMEX’s Arnie “Woo Woo” Ginsburg.)

At first, Clayton was a staff announcer, introducing pre-recorded features and programs from the NBC Blue network and sometimes playing a few songs to fill time until the next feature began. But his fortunes began to change when the Boston Herald Traveler newspaper acquired WHDH in 1945. By 1946, the new management was hiring up-and-coming talent (including Bob Elliott, soon to partner with Ray Goulding and become the beloved team of Bob & Ray).

Boston Ballroom, “Let’s Dance” theme song

There was a late afternoon shift open and Clayton went from announcing the occasional song or feature to having a program of his own, Boston Ballroom. Putting the word “ballroom” into the title of the show was very common during the big-band era, when announcers – who were just beginning to be called “deejays” in the late ‘40s – would utilize the power of imagination to make the listeners feel like they were at an actual ballroom, dancing to the biggest hits. This type of show always had a theme song; many used “Let’s Dance” by Benny Goodman, and Bob Clayton made that his theme song, too.

In the late 1940s, big-band music was at the height of its popularity so that’s what Clayton played. But even then, he quickly gained a strong reputation for knowing a hit when he heard one, or sensing which unfamiliar artist playing something other than big-band tunes had hit potential. Blessed with a warm and friendly voice, he was also someone his young listeners trusted. He seemed to enjoy reaching out to them and listening to their opinions.

Listener polls, Record hops

Clayton became renowned for his listener polls, in which he’d ask students at any given high school to take a survey and send him their top 10 songs. Not only would he play some of them on Boston Ballroom, but he also gave shout-outs to the school and the students.

He also became known for hosting dances known as “record hops,” then a relatively new term though it would become widely used throughout the ‘50s and into the early ‘60s. He made appearances all over eastern and central Massachusetts, mostly at high schools and youth-group events, drawing very enthusiastic crowds. Since there was never any hint of trouble or scandal at any of the hops, Clayton was popular not only with teens; even their parents thought favorably of him.

Introduction of 45s, Birth of rock ‘n’ roll

By 1952/53, industry-redefining new trends were taking place in the music business, including the shift away from 78 rpm records to 45s, which RCA Victor introduced in 1949. This made disc jockeys happy because the shellac 78s were heavy and hard to carry, while the much smaller, much lighter 45s were infinitely easier to take to events.

At the same time, young people began expressing interest in what was first called “rhythm and blues” (or R&B, previously called “ethnic music” by many), and within a year or two would be classified as “rock ‘n’ roll.” Some students who came to Clayton’s dances began asking for R&B songs, and through those requests he was introduced to a genre of music he had never played before. By his own admission, Clayton preferred big bands, melodic jazz and middle-of-the-road vocalists, but he wanted to make his audiences happy, of course. As the music morphed from R&B into rock ‘n’ roll, Clayton adapted to the new style and became a wildly popular deejay.

Defending teens’ choices, Influencing labels

When some of the parents objected – some vehemently – to rock’s driving beat and/or its questionable lyrics, he defended the teen audience and explained that the kids had every right to choose their favorite music, just as he had done when he was growing up. He reassured adults that most teens were basically “good kids” and that this new music would not affect them negatively. Coming from someone with Clayton’s credibility, this made an enormous difference in parents’ eventual acceptance of rock music.

Like most deejays of his time, Clayton was extremely influential. Because his program was so popular, artists knew that getting airplay on Boston Ballroom could increase record sales substantially, helping to make a song a hit or, in some cases, even rejuvenating an artist’s career. He had strong relationships with both major and minor record companies, and his choices of what to air sometimes influenced the decisions the labels made regarding which artists and/or songs they should promote most aggressively.

Norm Prescott feud, The Dee-Jay Quartet

In the years that Clayton was on the air, announcers could still pick their own music, and he enjoyed listening to all the new records that came in before deciding which ones he would add to his playlist or which artists he wanted to interview. Sometimes, however, his close friendships with record company executives got his competitors upset.

For example, all the top deejays wanted an exclusive whenever a new song by a major artist came out. And if Clayton got the song (and the exclusive) first, announcers at other stations tended to be resentful. He had an ongoing feud with his former WHDH colleague Norm Prescott (who moved to WORL, then WBZ) and while some of it was probably just showmanship, both men sniped at each other on air while claiming to play the hits first. Newspaper reporters were still writing about their quarrels many years later, noting that the dislike between the two certainly did not seem like an act.

On the other hand, Clayton and Prescott did bury the hatchet now and then, joining other Boston deejays to volunteer at various charity events. They even appeared together on a recording in 1956, when the Boston-based Pilgrim Records put out a Clayton-produced 45 by The Dee-Jay Quartet (“Down by the Riverside” b/w “Friendship”) featuring Clayton, Prescott, Dave Maynard, Joe Smith and Ned Powers.

Philanthropy, Artist management

Throughout his career, Clayton was rarely associated with controversy. He was well-known for his active involvement in philanthropy, supporting charitable causes like the March of Dimes; aiding Hungarian refugees who had escaped from the Soviet bloc and hoped to resettle in the US; and hosting an annual Christmas party for inmates at the Norfolk Correctional Institution.

In addition to doing his late afternoon air-shift and appearing at record hops, Clayton also dabbled in artist management. This would become a problem late in his career, but he never anticipated such a thing. One example was a very talented young singer from Medford named Emilie Marie Surabian, whom Clayton discovered in 1951, becoming her manager. She signed with MGM Records – the label changed her name to Cindy Lord – and in the 1950s she recorded many widely played songs, some as a solo performer and some as part of the duo of Cindy & Lindy (with vocalist Lindy Doherty).

Clayton played some of their songs on his show and would later insist there was no conflict of interest in doing so since he did not give Cindy’s or Cindy & Lindy’s records any special treatment. By mid-1956, however, he was no longer her manager, a split he always claimed was amicable and caused by his lacking sufficient time to devote to her career, not by any scandal.

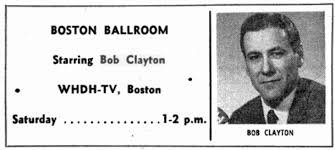

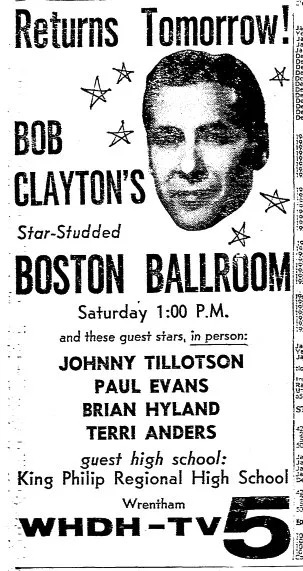

Newsweek “Top DJ,” Boston Ballroom TV show

In early 1957, Newsweek magazine ran a feature on the top disc jockeys in the United States; Clayton was on the list. By 1958, Boston Ballroom was so popular that the WHDH management wanted him to do a televised version. American Bandstand with Dick Clark had become a gigantic national hit – Clayton hosted the show in August 1958 when Clark was on vacation (one of only six deejay to ever fill in for Clark) – and local versions were popping up all across the US including Connecticut Bandstand (which debuted on WNHC-TV out of New Haven in October 1956).

The TV version of Boston Ballroom made its debut on a Saturday night in late March 1958; on that first broadcast, Clayton’s guests included such high-profile talent as Connie Francis, Frankie Avalon and Bill Haley & His Comets. Just as he had always done, Clayton invited a group of teens from a local high school to dance on the show and, since it promised to be an unforgettable experience, students from a number of schools competed to be chosen.

On his debut episode, the dancers came from Bridgewater High School; the next several shows featured dancers from Saugus High and Cambridge Catholic High. The students were always chaperoned by adults from each school, reinforcing the belief that if Clayton was hosting the event, parents had nothing to worry about. In 1959, the televised edition of Boston Ballroom won an award from the Cambridge School of Radio & TV. WHDH-TV aired the show until early 1963.

Payola scandal, Norm Prescott claims

The Payola Scandal, which unfolded in the late 1950s, tarnished – and in some cases ruined – the careers of many announcers nationwide. A number of very well-known disc jockeys admitted to a Congressional committee that they had taken money and other gifts from record companies in exchange for giving certain songs an extra push (or playing them at all); by far the most publicized example was Alan Freed, the legendary deejay credited with redefining and popularizing the term “rock ‘n’ roll,” whose reputation and career were utterly obliterated by the hearings.

When Clayton’s public arch rival Norm Prescott testified, he acknowledged that he had been among the deejays who accepted payola, but he also accused Clayton of unsavory practices, including making deals with record companies to get exclusives on new records or for interviews with artists/bands. Clayton denied such practices when he testified in February 1960, and he also denied ever taking payola.

He admitted that he had received Christmas presents and an occasional lunch from record promoters over the years, but explained that the total of what he had received was under $400 (about $4,200 in 2024). He vehemently denied Prescott’s claims, saying he had never entered into any financial arrangements with any record companies for exclusives. In the end, there were no negative repercussions from his testimony – undoubtably the result of his sterling reputation – and his career in broadcasting continued.

Retirement, Return to law, Death, Hall of Fame

After spending three decades on the air at WHDH, Clayton stopped doing any announcing work in the late 1960s to become the station’s music director, but he continued to champion songs and the various causes in which he believed. After retiring from radio in the early 1970s, he moved to Cape Cod, where he and his family had often vacationed in the summer, and went back to being an attorney.

Clayton died on February 4, 2002, at age 87. For his 30-year long and incredibly impressive career, he was inducted into the Massachusetts Broadcasters Hall of Fame posthumously in 2008.

(by Donna Halper)

Former deejay, music director and radio consultant Donna Halper is a Boston-based historian who has spent over three decades as a professor, teaching media-related courses at Emerson College, the University of Massachusetts and Lesley University. She’s the author of six books including Boston Radio: 1920-2010 (Arcadia Publishing, 2011) and has written articles for a variety of publications. Dr. Halper was inducted into the Massachusetts Broadcasters Hall of Fame in 2023.