Paul’s Mall / The Jazz Workshop

In the early 1950s, before rock ‘n’ roll replaced jazz in the hearts of America’s youth, Boston was among the swingin’est, jumpin’est, boppin’est places in the nation. With clubs like Wally’s Cafe Jazz Club, The Hi-Hat, Chicken Lane, the Savoy Cafe, the Ken Club, the Wig Wam, Morley’s, the Roseland-State Ballroom and Storyville, the city’s jazz scene was a panoramic showcase of the sweetest grooves, the hottest licks, the best-known bandleaders and the brightest new stars.

By the mid-1960s, though, jazz was well on its way to becoming a cottage industry compared to rock, its crass musical cousin. While venues like Music Hall and The Boston Tea Party capitalized on the seismic shifts in the public’s musical tastes, most jazz clubs were either struggling to stay afloat or out of business altogether. And with few exceptions, the owners of the remaining clubs had no bloody idea how to manage the new cultural and commercial realities.

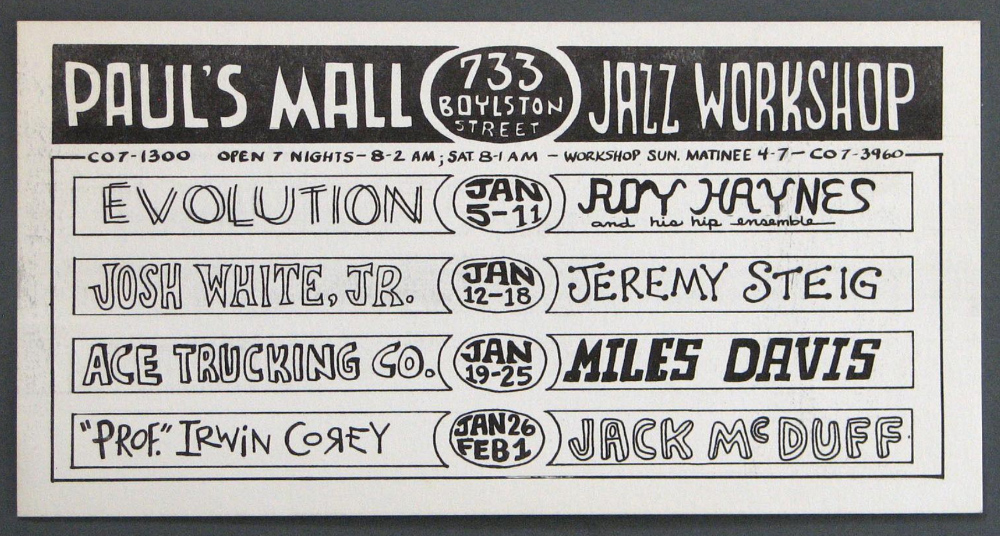

But Fred Taylor did. And that’s because he understood an essential element of concert promotion that his club-owning contemporaries didn’t: the paramount importance of artists’ “crossover appeal,” a concept as common today as multi-track recording but one that promoters and producers rarely considered very seriously in the 1950s and early ‘60s. By presenting a buffet of jazz greats, blues masters, up-and-coming rockers and budding pop stars at The Jazz Workshop and Paul’s Mall – the clubs he owned between 1965 and 1978, located side by side at 733 Boylston Street – Taylor became the driving force behind two of the most storied venues in New England’s musical history.

The Jazz Workshop: origins, opening

The seeds of The Jazz Workshop were planted in 1953, when saxophonists Charlie Mariano, Varty Haroutunian and Serge Chaloff, trumpeter Herb Pomeroy and pianists Ray Santisi and Dick Twardzik cofounded it as a music school on Stuart Street in Boston. In 1954, they relocated the Workshop to the basement of The Stable, a popular bar and jazz joint on Huntington Avenue.

In 1963, after The Stable was torn down to allow room for the Massachusetts Turnpike extension, the partners moved The Jazz Workshop once again, this time to the basement of The Inner Circle restaurant at 733 Boylston Street. Most significantly, they began hosting acts; Stan Getz and his band appeared on opening night.

Paul’s Mall: Ownership, strategy, capacity

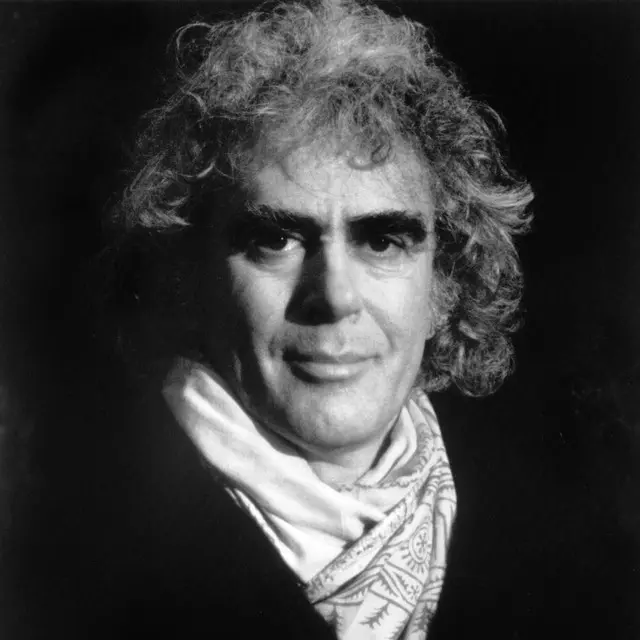

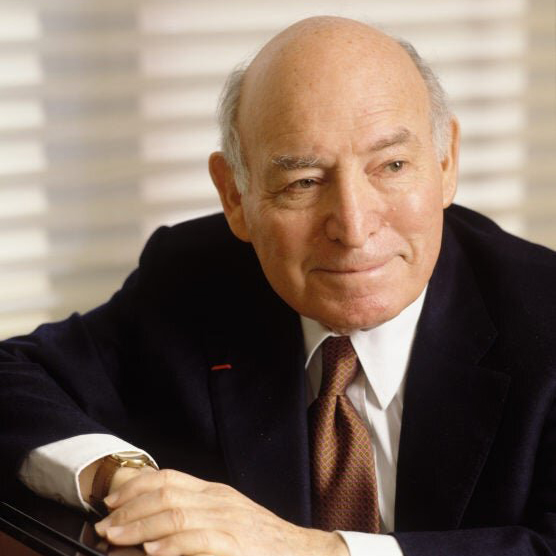

Getz had been booked for the debut Workshop gig by Fred Taylor, whose legacy as one of New England’s most legendary promoters is rivaled only by George Wein (founder of the Newport Jazz Festival and Newport Folk Festival), Manny Greenhill (founder of Folklore Productions) and journalist-turned-folk-blues impresario Dick Waterman. In 1965, Taylor and his business partner, Tony Mauriello, bought The Jazz Workshop and the space directly beside it, which they named Paul’s Mall; one set of stairs led down to the adjoining clubs. Taylor, who became known as “Mr. Jazz” in Boston jazz circles, booked the talent and Mauriello – who Taylor called “Mr. Facts and Figures” – handled the administrative side of the business.

Taylor’s strategy was as simple as it was novel at the time: to present a wide variety of acts between the two venues, hoping that their physical proximity would draw the broadest possible audiences – “crossover crowds,” to use the modern term that Taylor popularized, albeit unknowingly. “My whole idea was to have two sides,” he said in 2012. “You could have ‘the real thing’ in The Jazz Workshop and the more popular, contemporary stuff in Paul’s Mall.”

The 245-capacity Paul’s Mall was bigger than The Jazz Workshop, which held around 170, and had a significantly bigger stage. For those reasons, large bands always played at the Mall, not at the Workshop, as did all non-jazz performers; some jazz artists who drew crossover crowds, such as Miles Davis, appeared at both venues. From the outset, students from Berklee School of Music (now Berklee College of Music) comprised a significant part of the crowd at both clubs since the main campus at 1140 Boylston Street was just a short walk away.

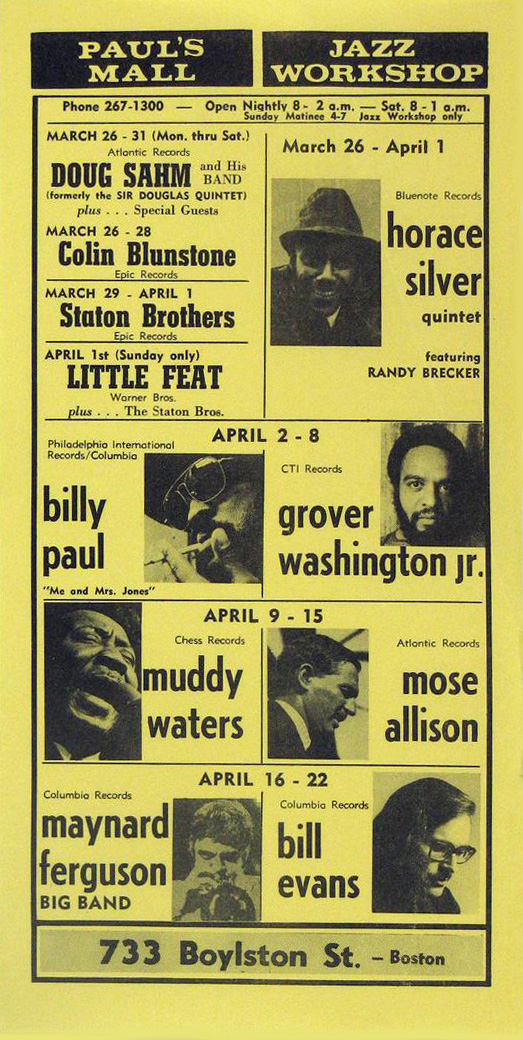

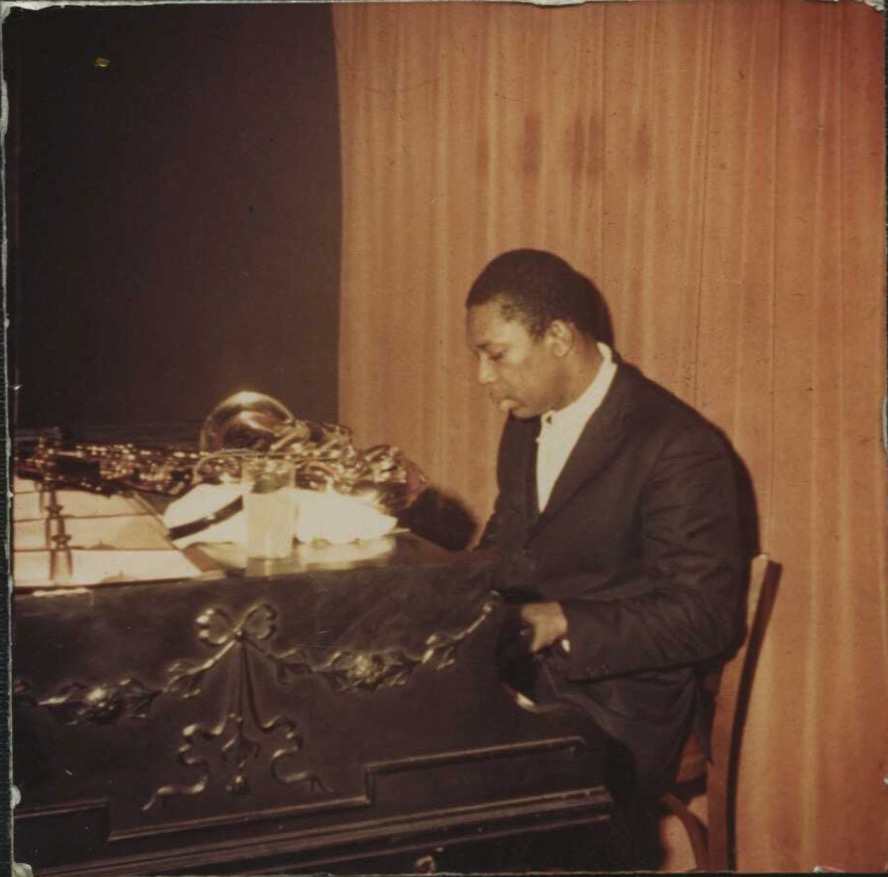

Notable appearances: jazz, blues

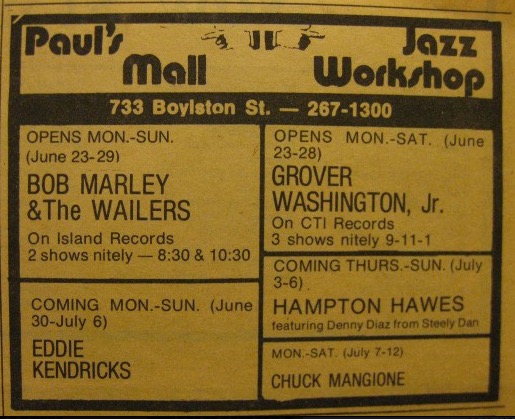

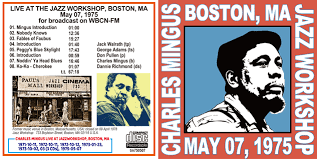

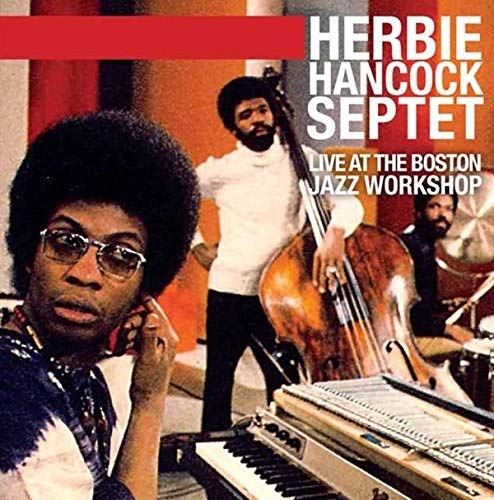

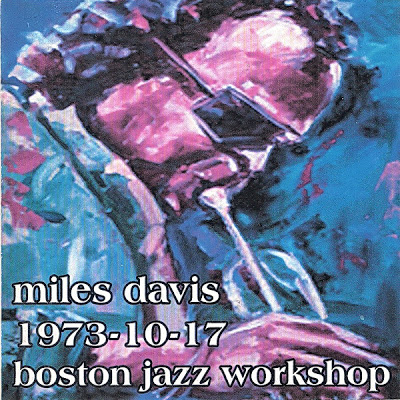

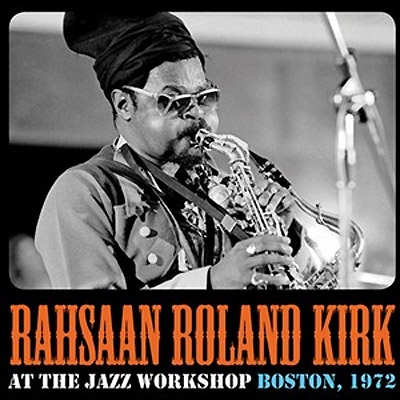

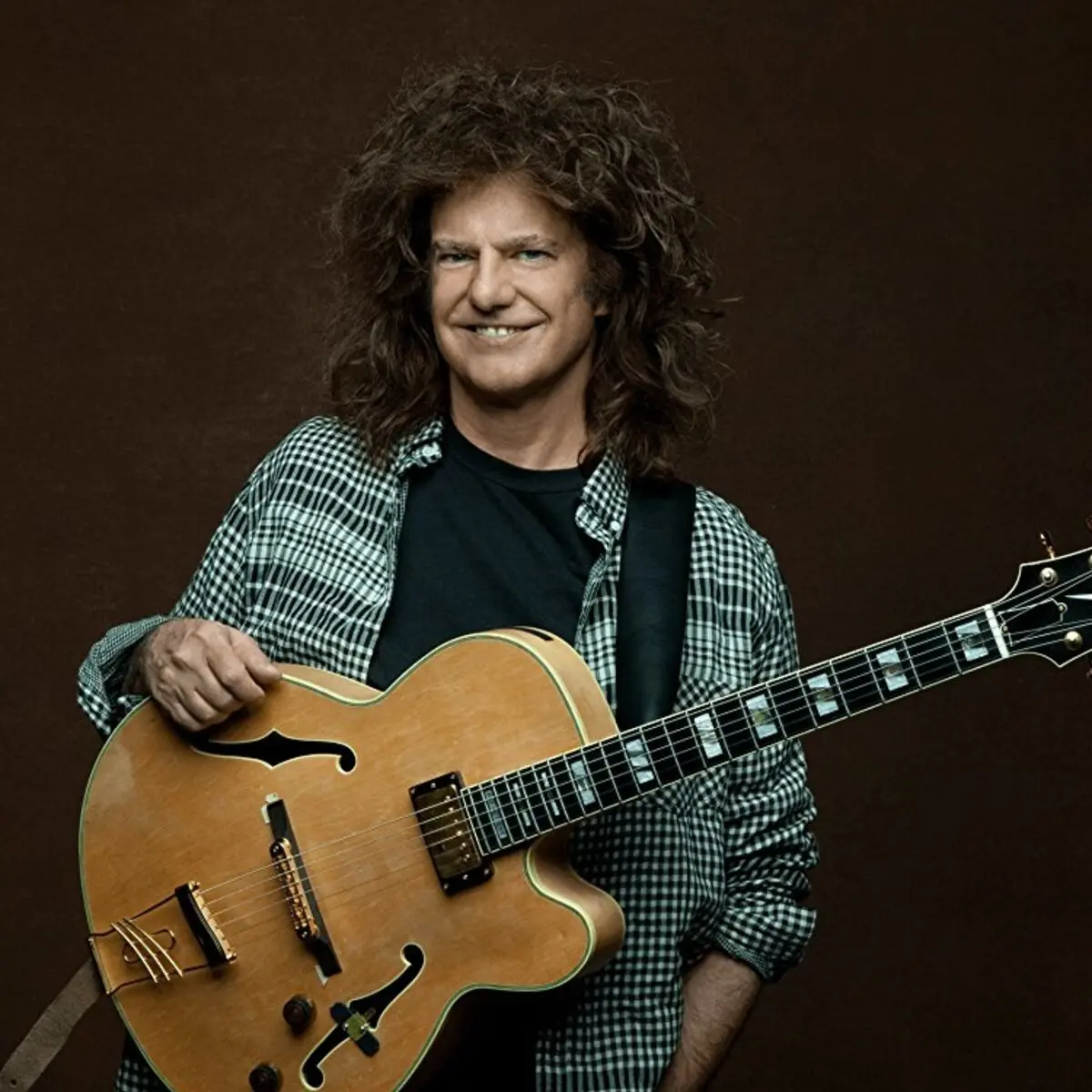

A dizzying assortment of jazz giants including Charles Mingus, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, Art Blakey and Ramsey Lewis appeared at The Jazz Workshop and Chuck Mangione, John Scofield, Al Di Meola, Tony Williams and Pat Metheny played there very early in their careers. Others artists included Ron Carter, Chick Corea, Ahmad Jamal, Mose Allison, Larry Coryell, Pharoah Sanders, Eumir Deodato, Joe Farrell, Earl Klugh, Grover Washington, Jr., Keith Jarrett, Bill Evans, Erroll Garner, Joe Williams, Betty Carter, The Modern Jazz Quartet, Cannonball Adderley, Les McCann, Herbie Hancock, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Sam Rivers, Archie Shepp, Charlie Byrd and Elvin Jones.

Of the big bands that Paul’s Mall hosted, those led by Duke Ellington, Don Ellis, Maynard Ferguson and Gene Krupa played a number of shows. Sun Ra and his Arkestra appeared with their long-time saxophonist Pat Patrick, the father of former Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick.

In July 1971, Weather Report played their very first gig anywhere at the Mall, the result of Taylor’s strong relationships with the band’s cofounders, Wayne Shorter and Joe Zawinul. Also in 1971, Talyor brought in Latin-jazz-dance groups led by percussionists Mongo Santamaria and Willie Bobo since he was sure they had substantial crossover appeal, even though Latin jazz wasn’t particularly popular at the time.

Local jazz artists appeared, too, including Charlie Mariano’s Laugh and Cry, trumpeter Claudio Roditi’s Os Cinco, singer-songwriter Ralph Graham’s jazz-funk ensemble, guitarist Chris Rhodes and vocalist Carol Sloane. Boston-based blues groups including The James Montgomery Band and The Colwell-Winfield Blues Band took to the Mall’s stage and blues icons Muddy Waters, B.B. King, T-Bone Walker and James Cotton played multi-night stands.

Notable appearances: rock, pop, r&b, soul

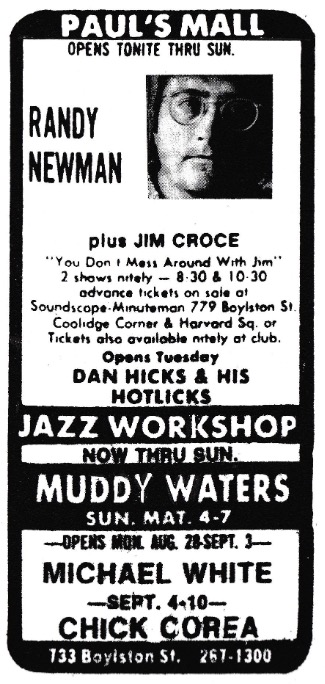

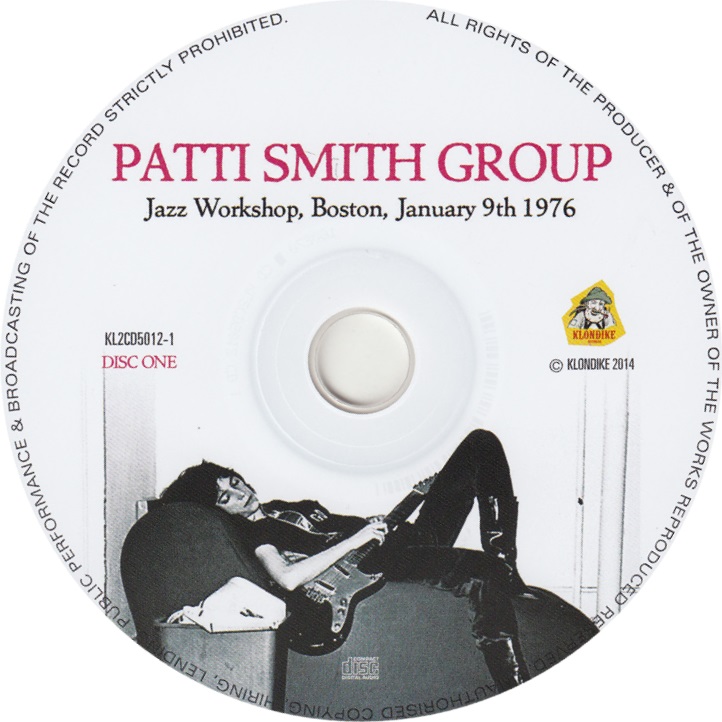

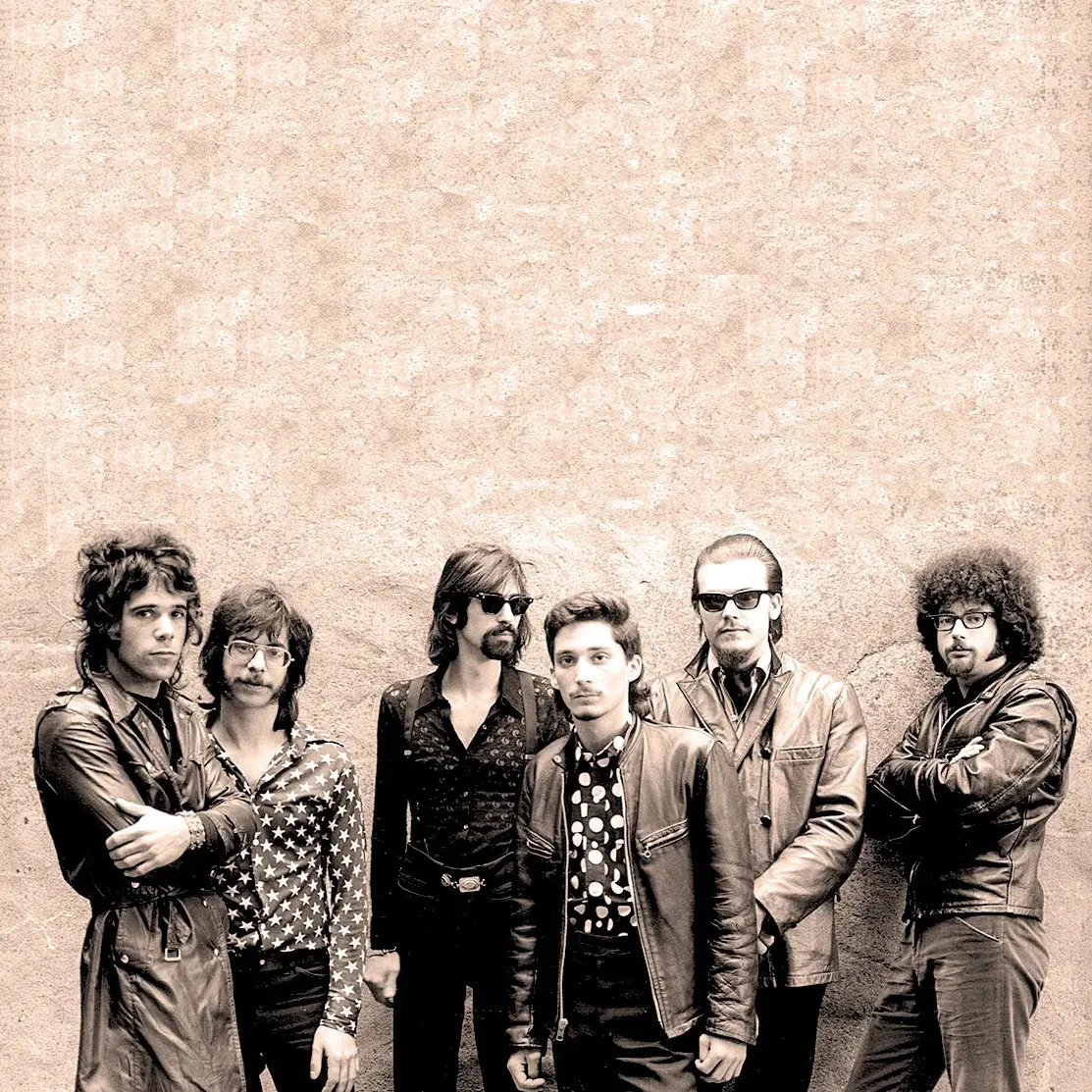

Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley and Little Richard also played multi-night stands at the Mall, but the club was mostly a place to see up-and-coming rock, pop, R&B and soul acts, not ‘50s-era ones. Between the late ‘60s and late ‘70s, a jaw-dropping assortment of new and future stars appeared including Linda Ronstadt, Billy Joel, Jim Croce, Bette Midler, George Benson, The Chi-Lites, Aerosmith, Earth, Wind & Fire, John Cale, The Pointer Sisters, Little Feat, The Four Freshmen, Lou Rawls, The Persuasions, The J. Geils Band, LaBelle, Kool & the Gang, Gil Scott-Heron, The Incredible String Band, Roger McGuinn, The Meters, Jerry Garcia, The Charlie Daniels Band, Patti Smith Group, Tavares, New Riders of the Purple Sage, Greg Khin Band, Randy Newman, Jimmy Buffet and Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers.

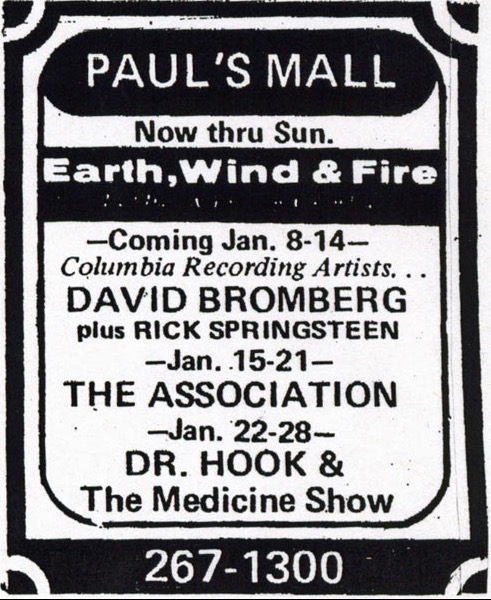

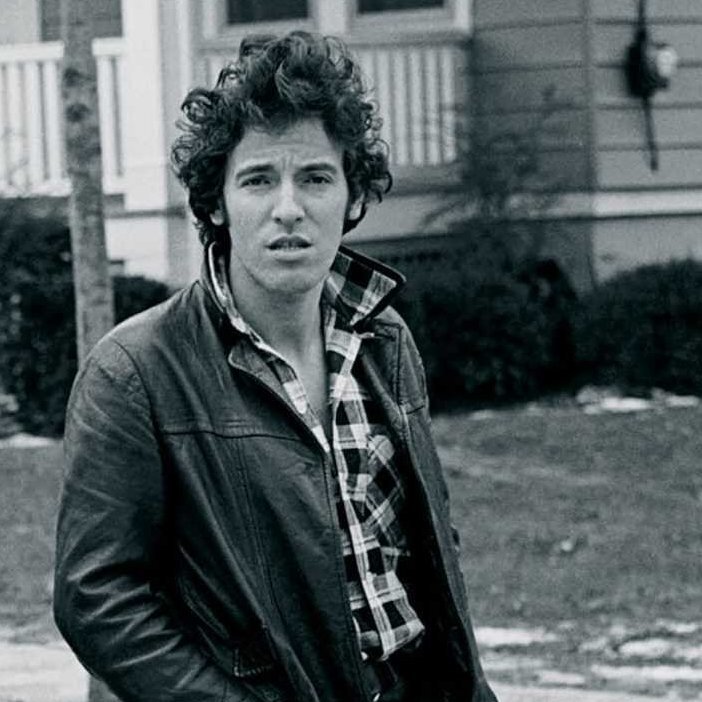

Springsteen’s Boston debut, Manilow’s first solo shows

In January 1973, Bruce Springsteen played a seven-day, 14-show stand at the Mall, opening for Americana pioneer David Bromberg (and mistakenly billed as “Rick Springsteen”). They were his first-ever gigs in Boston and the headliner graciously allowed the newcomer and The E Street Band up to 80 minutes on stage for every show. During his time in the city, Springsteen, E Street Band saxophonist Clarence Clemons and a few other band members visited the WBCN studios; Maxanne Sartori interviewed them on the air and they played three songs, including “Blinded by the Light.” In an August 1992 show at the Centrum in Worcester, Springsteen mentioned Paul’s Mall before playing “Grown’ Up,” telling the audience that he’d performed the song there 20 years before.

In October 1974, Barry Manilow made his first-ever solo appearances at the Mall during a two-week stand as the opening act for jazz trumpeter Freddie Hubbard. “It was a horrible experience,” he told the Boston Globe’s Lauren Daley in 2022. “I was terrible; I didn’t know what I was doing. But the audience didn’t agree. By the end of those two weeks, there was a really healthy audience who was applauding, laughing. Everything started at Paul’s Mall in Boston for me.”

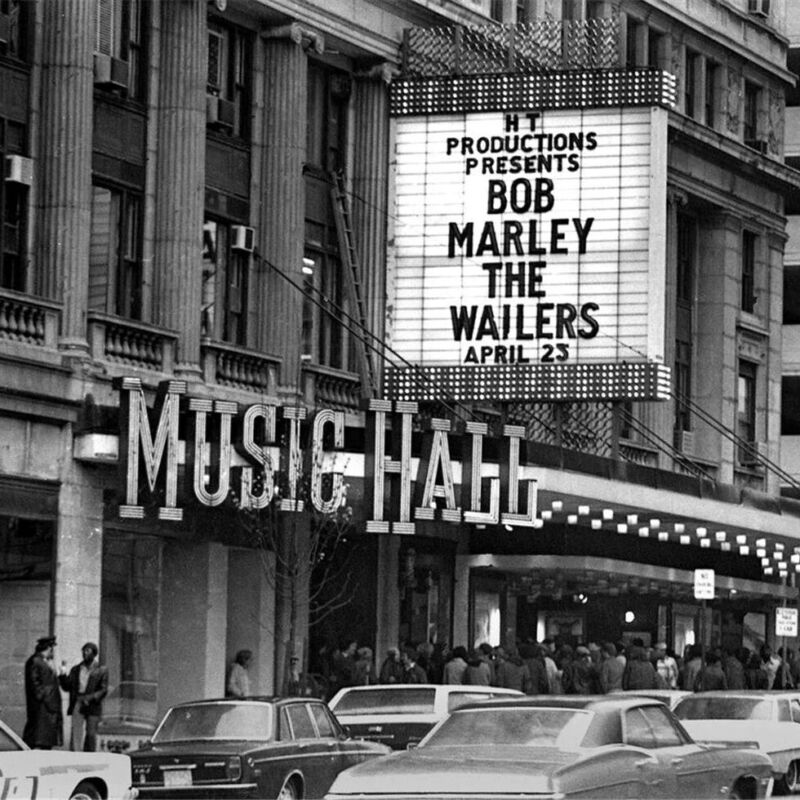

Bob Marley & the Wailers’ first U.S. concerts

In July 1973, Bob Marley & The Wailers made the Mall the first stop of their first US tour, playing a six-night stand to support their LP Catch a Fire, which Island Records had released in April. In a move that helped secure the station’s place as Boston’s premier FM station, WBCN aired the first of the six concerts live. The station had done a live broadcast from the Mall before – Miles Davis’ show in September 1972 – and went on to simulcast Keith Jarrett’s September 1974 appearance at The Jazz Workshop.

After making their American debut at the Mall – arguably the venue’s most historic non-jazz event – Marley and The Wailers did a four-night stand at Max’s Kansas City in New York City on a double bill with fellow legends-in-waiting Bruce Springsteen and The E Street Band, followed by appearances in Philadelphia, Denver, Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Notable live recordings

In 2015, Klondike Records released the WBCN simulcast of Marley’s opening night at the Mall (July 11, 1973) as Live ’73 Paul’s Mall, Boston, Ma. In addition to that and numerous bootleg LPs from shows by Aerosmith, Patti Smith Group and others, a flock of esteemed jazz, fusion and blues acts recorded official live albums at the Mall and The Jazz Workshop.

Examples include Charles Mingus’ Live at the Jazz Workshop, 1971 and Jazz Workshop 1973; Miles Davis’ Paul’s Mall, Boston, Sept 1972 and Boston Jazz Workshop 1973-10-17; Rahsaan Roland Kirk’s At the Jazz Workshop Boston, 1972; Return to Forever’s Jazz Workshop Boston, MA, May 15, 1973; Herbie Hancock & The Headhunters’ Paul’s Mall Jazz Workshop November 1973; The Elvin Jones Quartet’s Jazz Workshop Boston 1973; Doug Sahm’s Paul’s Mall Boston, MA, March 29th, 1973; The Keith Jarrett Quartet’s Definitive Boston 1974; Muddy Waters’ Live ’76, At Paul’s Mall, Boston; and Pat Metheny’s Live: The Jazz Workshop, Boston, Mass. 21 Sep ’76.

Closing, Taylor’s later career

Both The Jazz Workshop and Paul’s Mall closed in April 1978. The final show at the Workshop was on April 8th, when vibraphonist Milt Jackson of The Modern Jazz Quartet appeared with his own group, and B.B. King played the final show at Paul’s Mall on April 9th.

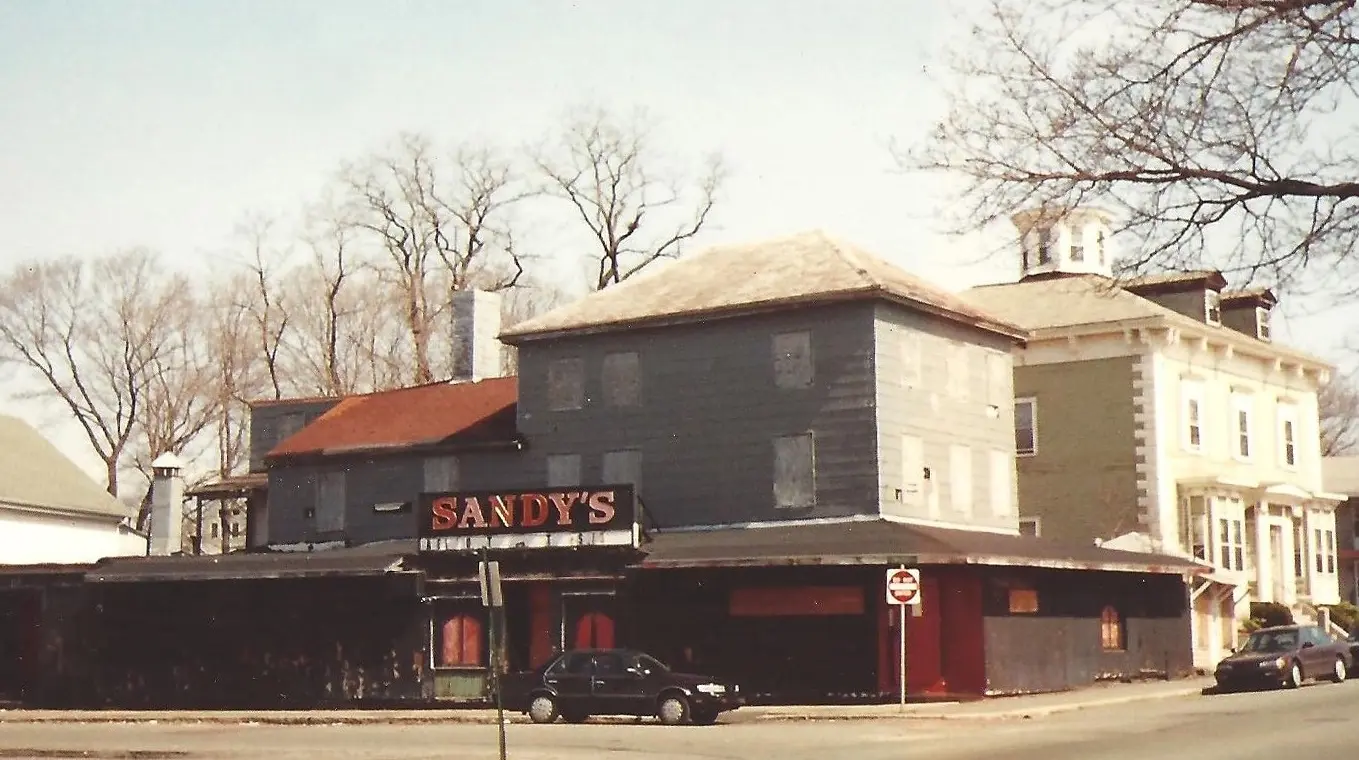

On April 10th, in an article headlined “Paul’s Mall/Workshop Closes; 15 Years of Jazz Ends,” Scott A. Kripke of The Harvard Crimson reported the reason for the clubs shutting down: “Owner Fred Taylor has said that the Boston clubs can no longer afford to stay open. Great jazz performers are just too expensive for a club-sized room, which can fit only 150 to 200 people.” The clubs’ closings, Kripke wrote, “left Boston with no place for club-style, top-name jazz, save Sandy’s Jazz Revival, which is 45 minutes north – in Beverly.” Sandy’s closed its doors seven years later, in 1985.

After shutting down the Workshop and the Mall, Taylor and Mauriello bought the 1,640-seat Harvard Square Theater, which they’d been leasing since 1976. They sold it to the AMC Loews chain in 1986, and from 1990 to 2017 Taylor was the entertainment director at Scullers Jazz Club in Boston.

Taylor’s death, Memoir

In 2019, Taylor died at age 90. In 2020, Backbeat Books published the memoir he cowrote with Boston-based jazz historian Richard Vacca, What, and Give Up Showbiz?; Six Decades in the Music Business, in which Taylor provides background and anecdotes about his years running The Jazz Workshop and Paul’s Mall. In a review for JazzTimes, former Boston Globe jazz critic Steve Greenlee called the book “less a memoir with a narrative arc than a collection of memories” written in a “casual, folksy style“ but said that it was worth reading as a kind of lighthearted history text. “For a student of Boston’s entertainment scene, it’s fascinating stuff,” he wrote.

(by D.S. Monahan)