Sandy’s Jazz Revival

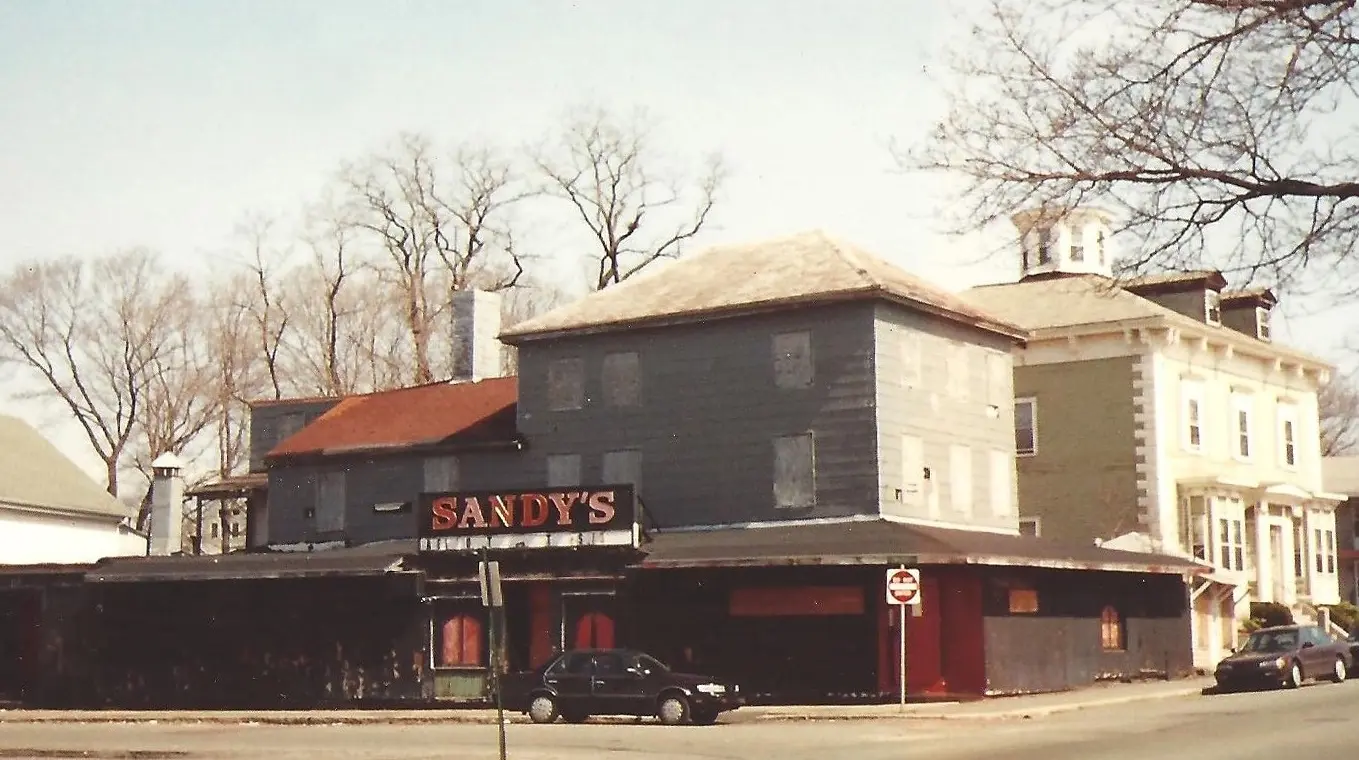

Take a less-than-ten-minute stroll down Cabot Street in Beverly, Massachusetts, starting at the Cabot Performing Arts Center – “the Cabot” to locals – and head toward the Essex Bridge – “the Beverly-Salem Bridge” to locals. At the corner of Cabot and Edwards Streets on your right – where condos now stand – you’ll see the former location of a venue that was just as cherished as the Cabot, but not for vaudeville, films and magic shows. Sandy’s Jazz Revival – “Sandy’s” to locals – was famous for…well, the clue’s in the name.

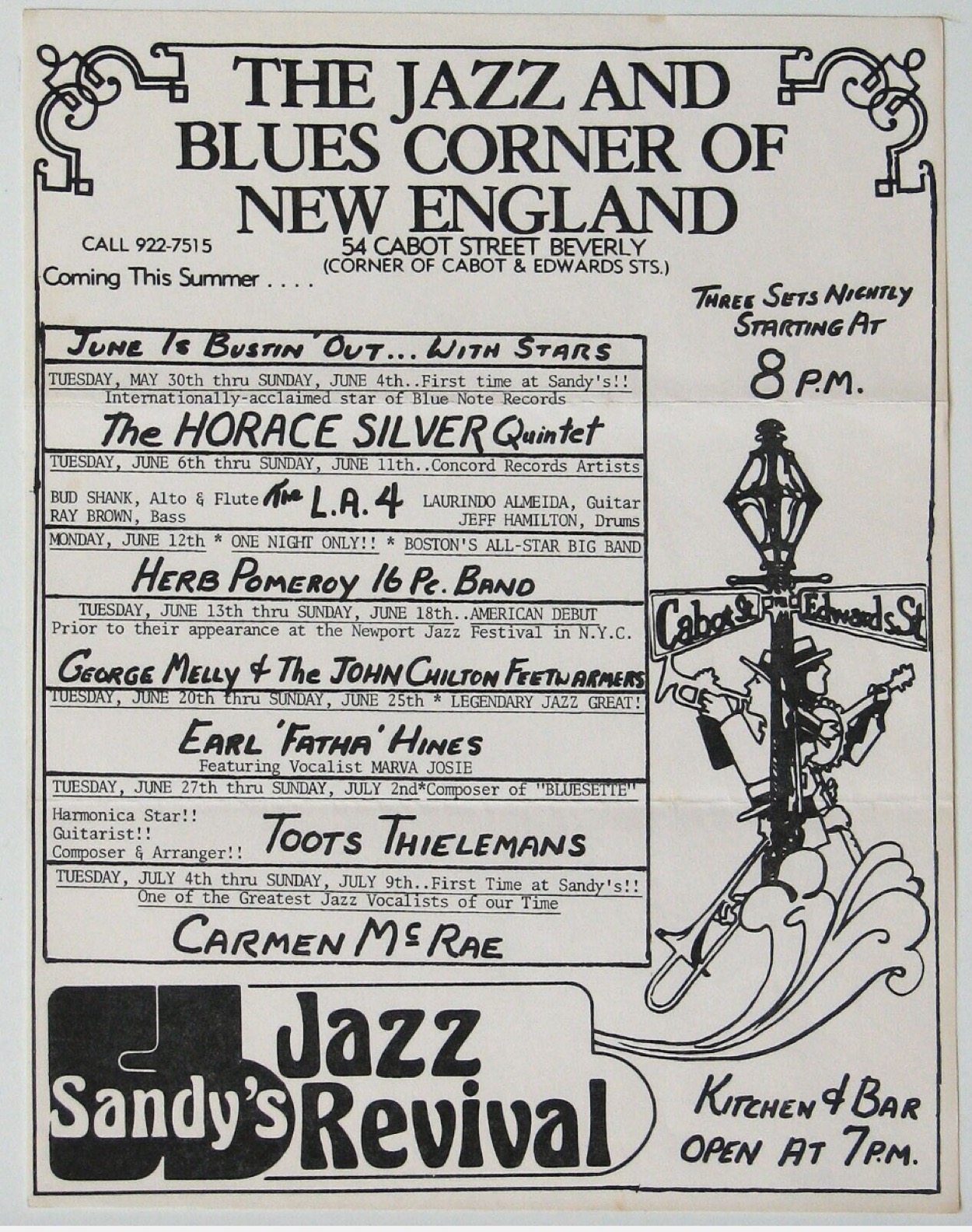

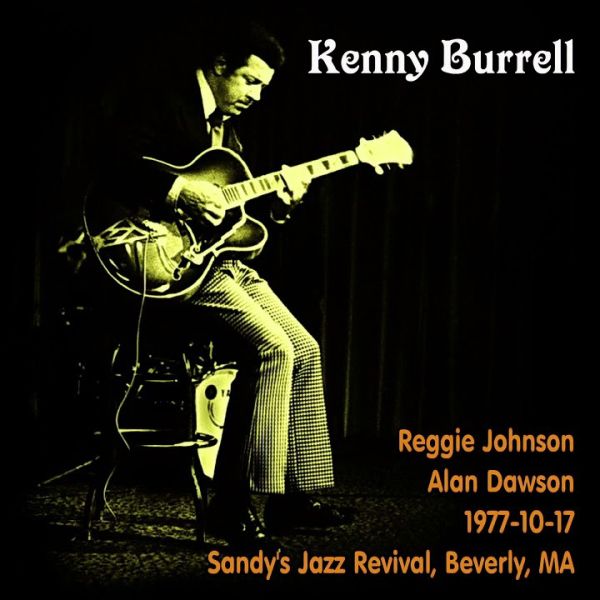

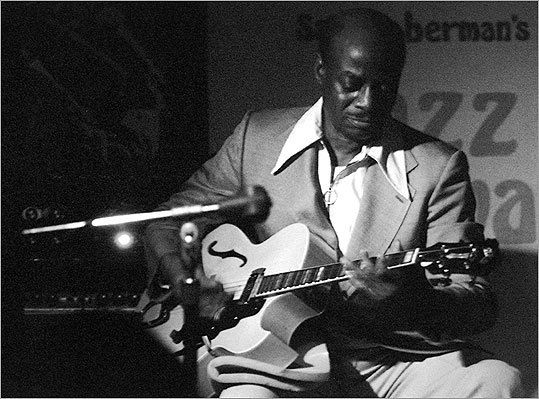

But the name was somewhat misleading, since throughout its 52-year existence the Sandy’s roster was almost equally balanced between jazz and blues acts, with a few rockers thrown in here and there. Until closing in 1985, the venue hosted a formidable assortment of household names including Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Louis Armstrong, Thelonious Monk, Erroll Garner, Stan Getz, Buddy Rich, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Chet Baker, Buddy Tate, Tiny Grimes, Toots Thielemans, Larry Coryell, Kenny Burrell, Louis Armstrong, Buddy Guy, Junior Wells, Big Joe Turner, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Sonny Terry and John Lee Hooker.

Opening, Notable appearances

Opened in 1932 by the Berman family as a dining and dancing spot, the venue became a live-jazz club in 1933, the year Prohibition ended. In 1950, 27-year-old Sandford “Sandy” Berman took over the business, named it Sandy’s Melody House, then changed the name to Sandy’s Jazz Revival within the first year to reflect the nature of the club more accurately.

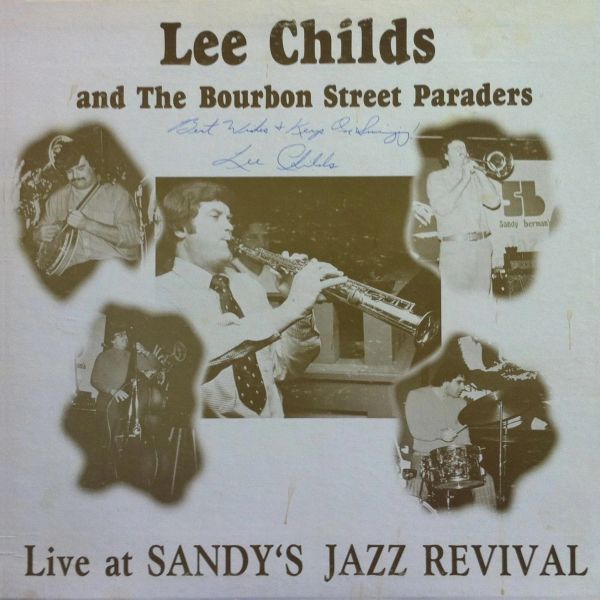

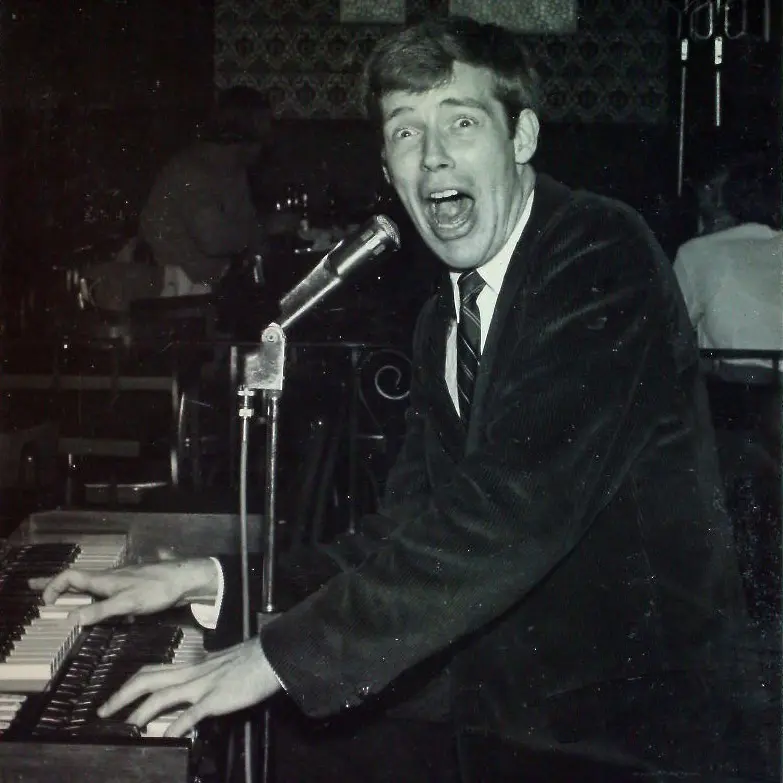

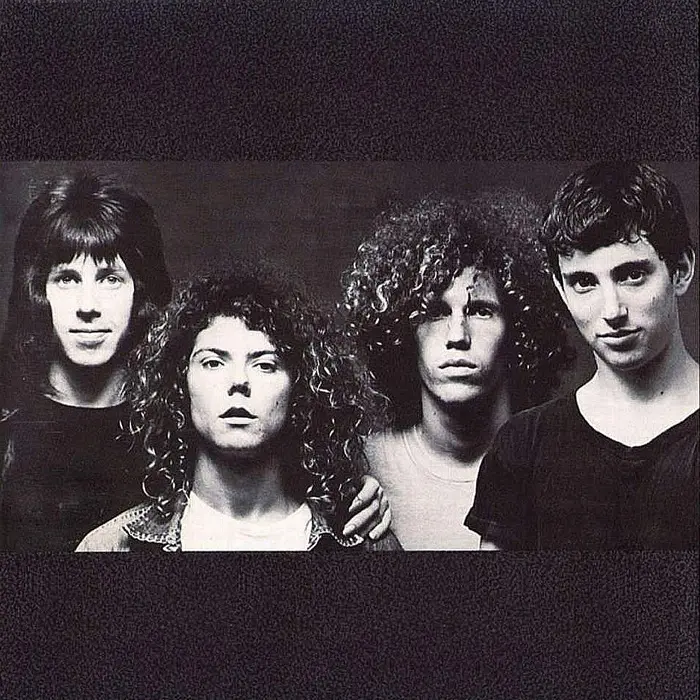

A number of artists with deep roots in New England played at Sandy’s including Springfield, Massachusetts native and renowned alto sax and clarinet virtuoso Phil Woods; Rhode Island-based blues and swing-revival big band Roomful of Blues; Duke Robillard (both with Roomful, the group he co-founded in 1967, and as a solo act); clarinetist Lee Childs, a Wellesley, Massachusetts, native; folk-blues singer-songwriter Ray Bonneville, who was born in Quebec but moved to Boston as a teenager; Malden, Massachusetts, native and boogie-woogie dynamo Preacher Jack; The Modern Lovers; and Boston-born blues barker George Leh, who in 1982 and ‘83 was the club’s regular opening act. In 2007, a clip of Preacher Jack and Leh playing together on the Sandy’s stage went viral on YouTube.

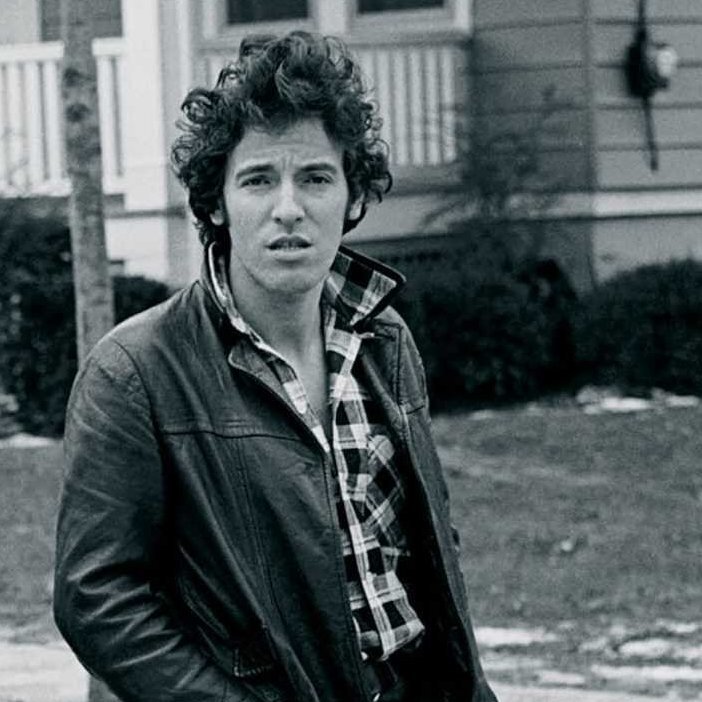

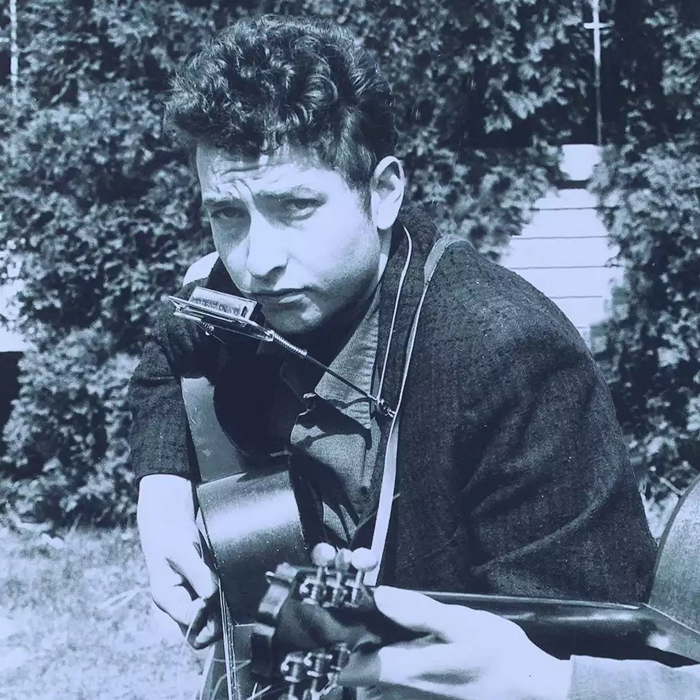

On December 21, 1973, a skinny, scruffy, scrappy 24-year old from Freehold, New Jersey, named Bruce Springsteen appeared – “the new Dylan,” as the mainstream rock press had christened him – five weeks after Columbia had released his second album, The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle, and 19 months before the label issued his iconic Born to Run LP.

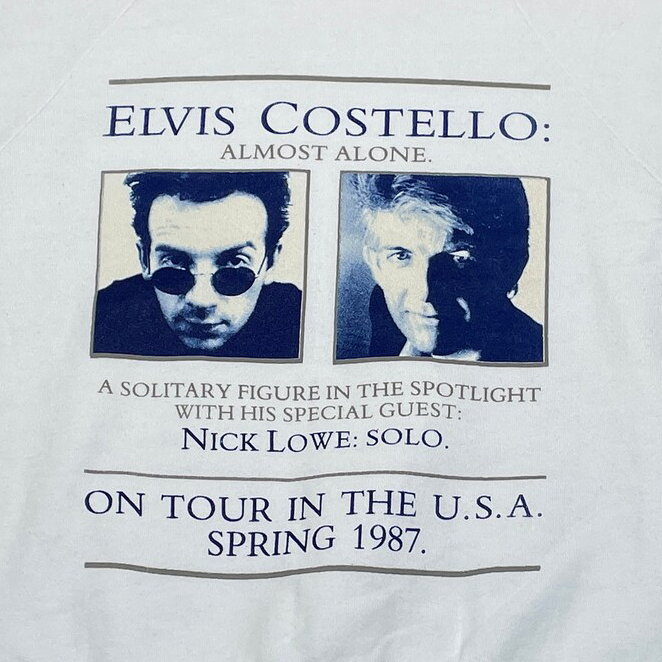

Other acts that took the Sandy’s stage included French-Italian violinist Stéphane Grappelli (1973), famous for his work in the 1930s with trailblazing guitarist Django Reinhardt; Graham Parker (1973), the London-born singer-songwriter classified along with Paul Weller, Elvis Costello and Joe Jackson as the UK scene’s “angry young men”; Florida-based psychedelic-folk band Pearls Before Swine; avant-garde saxophonist-flautist David Liebman; and Rahsaan Roland Kirk (1977, 1983), an American multi-instrumentalist as renowned for his hilarious onstage banter and political diatribes as for his ability to play several instruments simultaneously.

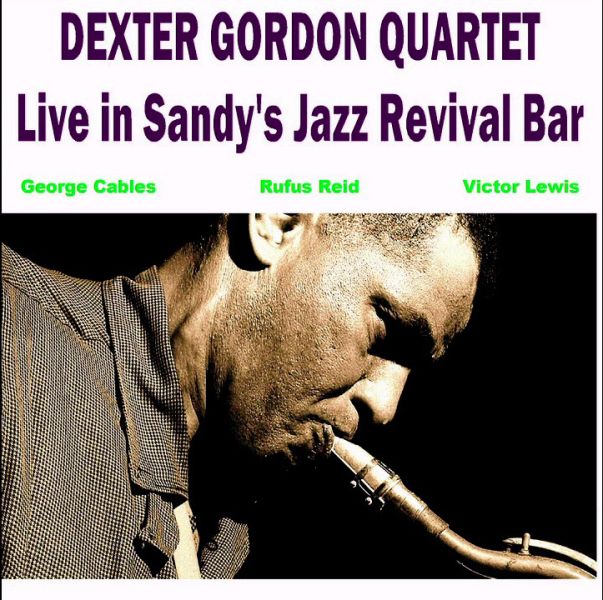

WGBH Weekly Radio Series, Notable Live Recordings

From 1965 to 1977, WGBH in Boston aired a weekly radio series featuring 30-minute performances broadcast live from Sandy’s. Hosted by Herb Pomeroy – a Gloucester, Massachusetts, native and trumpeter who toured with Lionel Hampton and Stan Kenton and founded the MIT Festival Jazz Ensemble – the list of artists who played on the program includes pioneering jazz violinist Joe Venuti, tenor saxophonists Dexter Gordon and Illinois Jacquet and jazz singer Joe Williams, famed for his solo work and frequent appearances with Count Basie and Lionel Hampton.

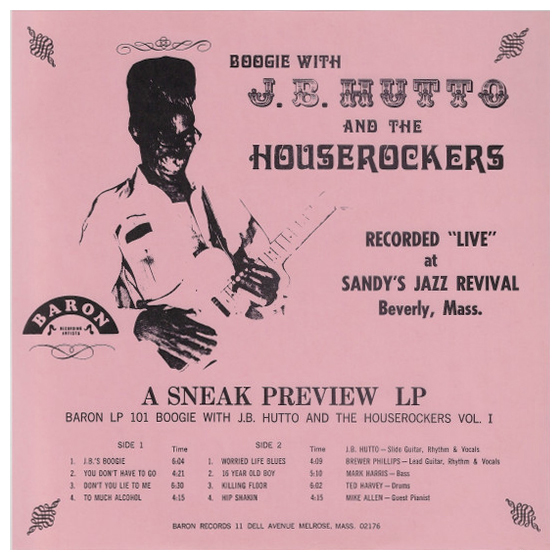

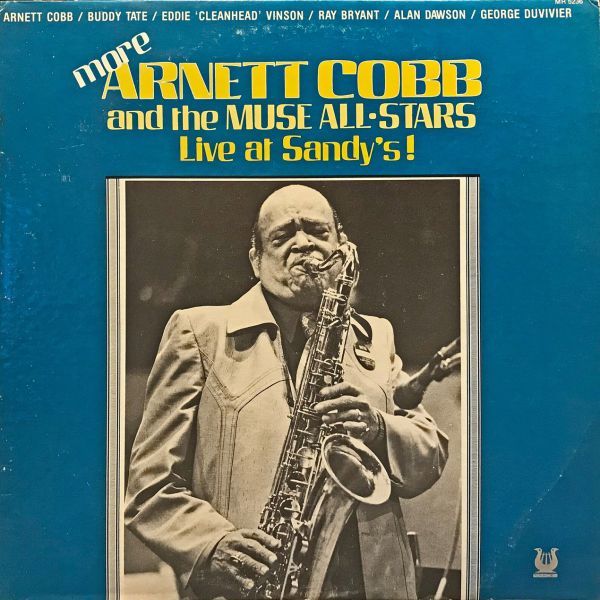

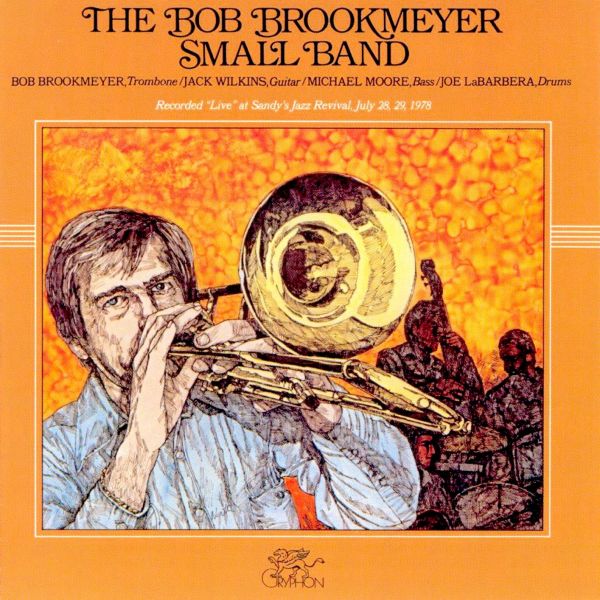

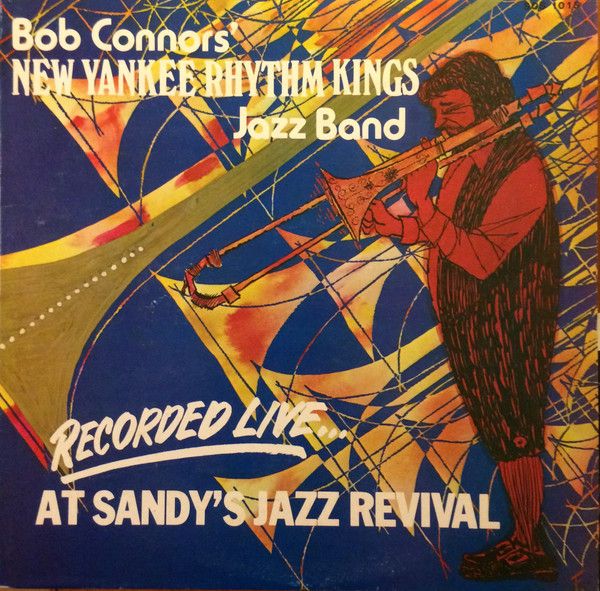

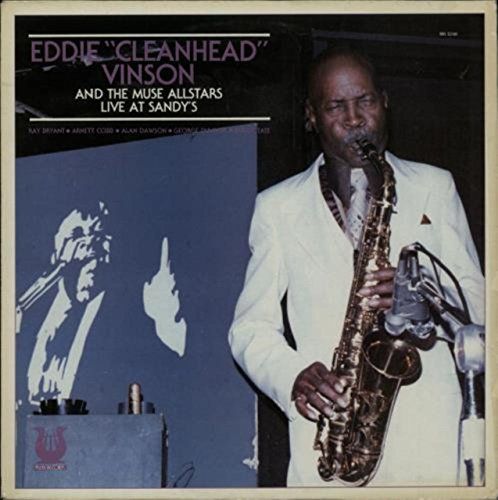

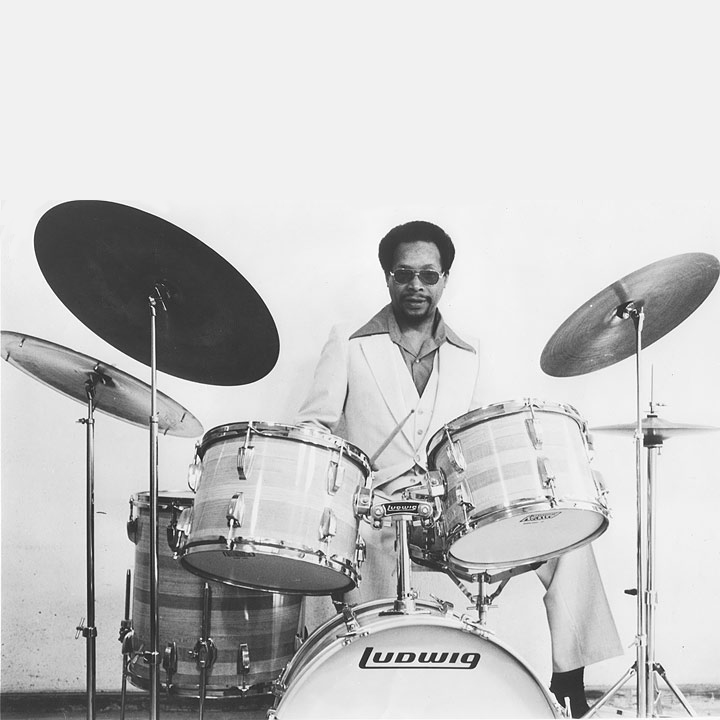

A number of live albums were recorded at Sandy’s including the Dexter Gordon Quartet’s Live in Sandy’s Jazz Revival Bar (1977); the Bob Brookmeyer Small Band’s Live at Sandy’s Jazz Revival (1978); Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson’s Live at Sandy’s (1978, featuring drummer Alan Dawson); Arnett “the Wild Man of the Tenor Sax” Cobb’s Live at Sandy’s! (1980); J.B. Hutto and The Houserockers’ Recorded Live At Sandy’s Jazz Revival, Beverly, Massachusetts, Volume One (1980); Bob Connors’ New Yankee Rhythm Kings Jazz Band’s Recorded Live…At Sandy’s Jazz Revival (1980); and Lee Childs & the Bourbon Street Paraders’ Live at Sandy’s Jazz Revival (1981).

North Shore Jazz Project, Legacy

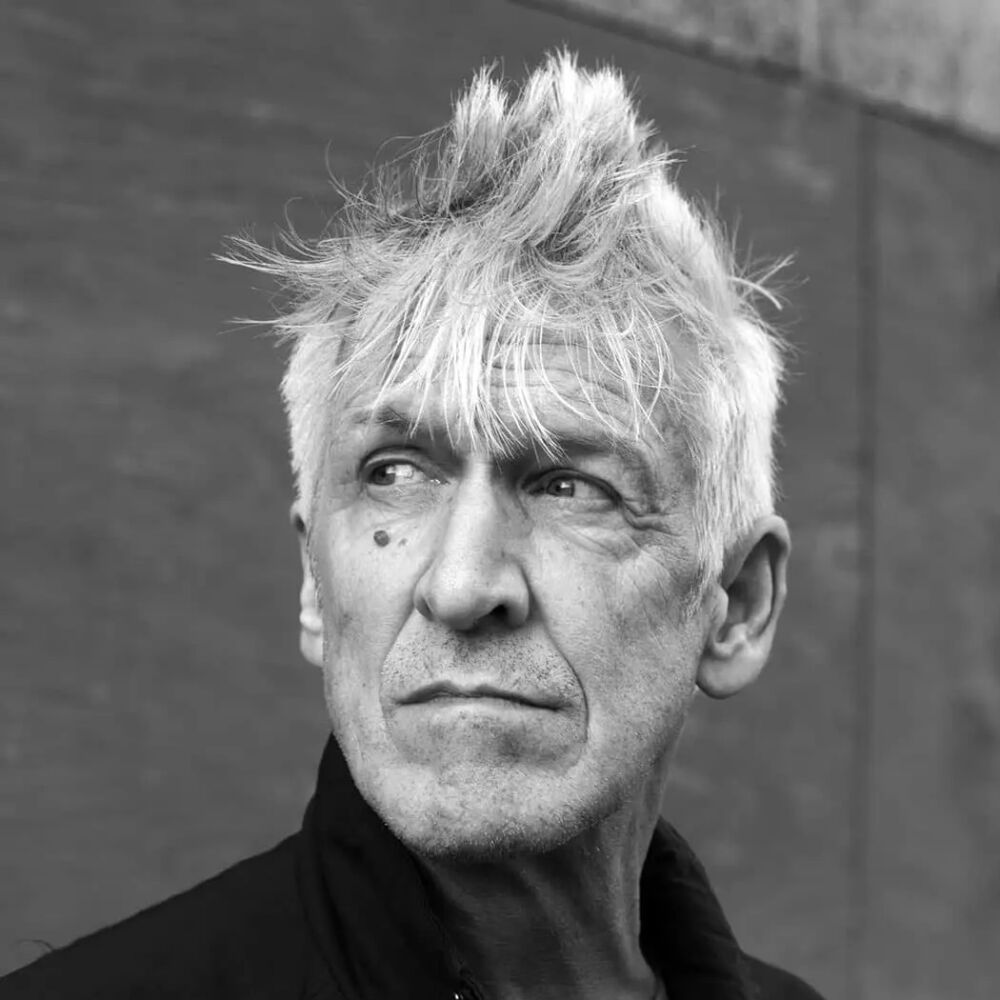

In 1983, Berman started working with Henry Ferrini, a Gloucester native, saxophonist, television producer and frequent patron at Sandy’s, to make a documentary about the club to celebrate its 50th anniversary. Although they didn’t complete the film before Berman’s death in 1991 at age 68 and the documentary never came to fruition, 18 years later Ferrini launched the North Shore Jazz Project (NSJP) – a nonprofit dedicated to educating young people about jazz and blues – as what he called “an extension of Sandy’s original vision.”

“Sandy had a vision of educating students,” he said in a 2009 interview with The Salem Evening News. “Continue his legacy, continue his vision – that’s what I wanted to do.” One of the project’s advisors is soul/R&B vocalist and local legend Barrence Whitfield, a Boston University graduate best known for fronting Barrence Whitfield and the Savages.

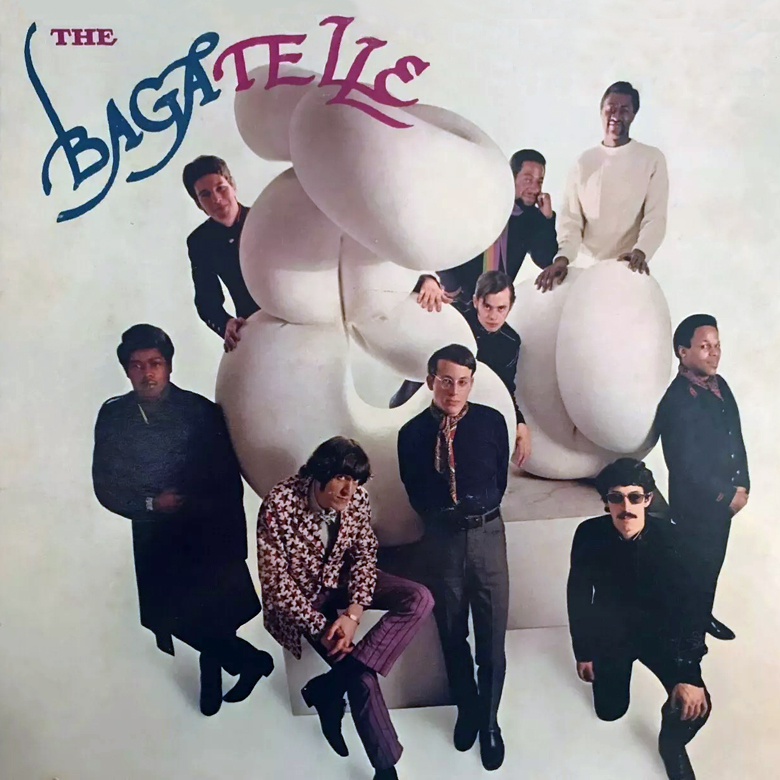

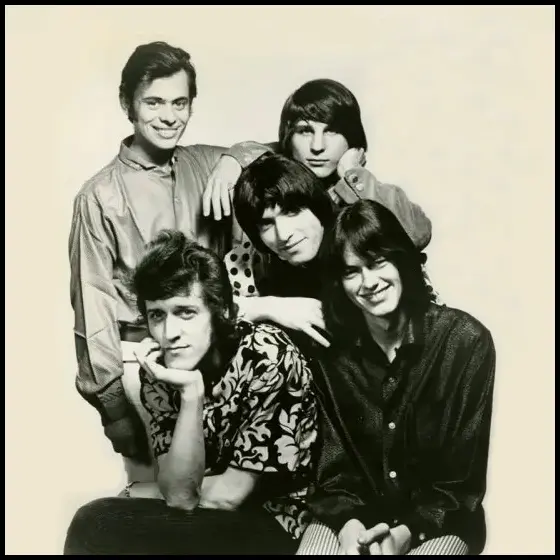

In August 2009, Chianti restaurant in Beverly hosted a launch event for the NSJP as a fundraiser with appearances by Willie Alexander (formerly of The Lost, The Bagatelle and The Velvet Underground), saxophonist Marky Early, guitarist and Ipswich native Roger Brockelbank, John Hyde (lead vocalist of the early-‘70s band Hokus Pokus), clarinetist Alek Razden of Rockport, Gloucester-based guitarist Dave Saginaro and vibraphonist Rich Greenblatt, a professor at Berklee College of Music.

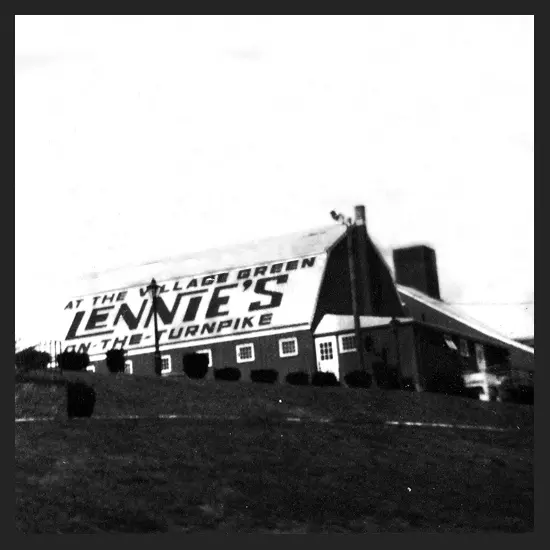

Asked about the historical and cultural significance of Sandy’s Jazz Revival, Ferrini compared it to another beloved New England jazz venue that’s been shuttered for decades. “Sandy’s – along with Lennie’s on the Turnpike – was the place where people could stand close to a performer and say ‘wow!,’” he said. “The club was not just a Beverly tradition, but a North Shore jazz tradition.”

(by D.S. Monahan)