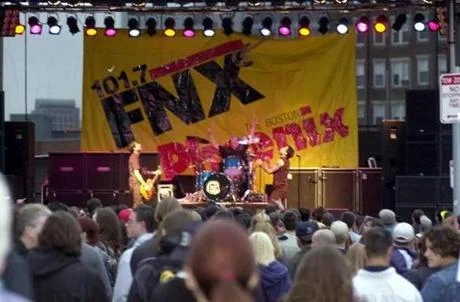

WFNX

On April 11, 1983, WFNX established the iconoclastic tone it kept for 29 years by starting its first broadcast with The Cure’s “Let’s Go to Bed.” Released five months before, the track hadn’t made any US charts but had reached #44 in the UK, #15 in Australia and #17 in New Zealand, each location thousands of miles from the station’s studio at 25 Exchange Street in Lynn, Massachusetts.

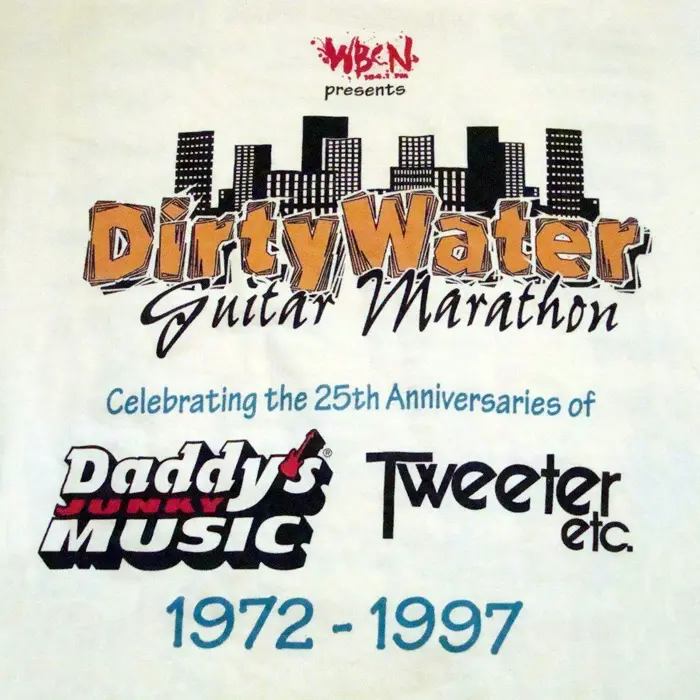

And from that three-and-a half-minute post-punk popper onward, Boston-area rockers with an ear for the alternative tuned in to ‘FNX as a part of their daily routine, 101.7-FM being their go-to spot for bands like Violent Femmes, Prefab Sprout, Echo and the Bunnymen, Suicidal Tendencies and New Order, to name a few, along with regular doses of reggae and jazz. In the summer of ‘83, when WBCN (“The Rock of Boston”) had The Police’s Synchronicity in heavy rotation and WAAF (“The Only Station That Really Rocks”) was doing the same with Iron Maiden’s Piece of Mind, WFNX (“Rock the Boat Radio” aka “The New Rock on the Block”) hit listeners with tracks from Murmur and War, the latest albums from pre-megastardom R.E.M. and U2, respectively.

Known for its pirate-radio vibe and thoroughly punked-up refusal to pursue lowest-common-denominator programming, the station appeared in Rolling Stone’s list of “10 Stations in the Country That Don’t Suck” several times and won four Station of the Year awards from the influential radio-industry trade publication Gavin Report. WFNX’s commitment to its counterculture mission and free speech in general endeared it to generations of listeners and – like WBCN had when it launched in early 1968 – reconfirmed Boston’s status as a nationwide broadcasting leader.

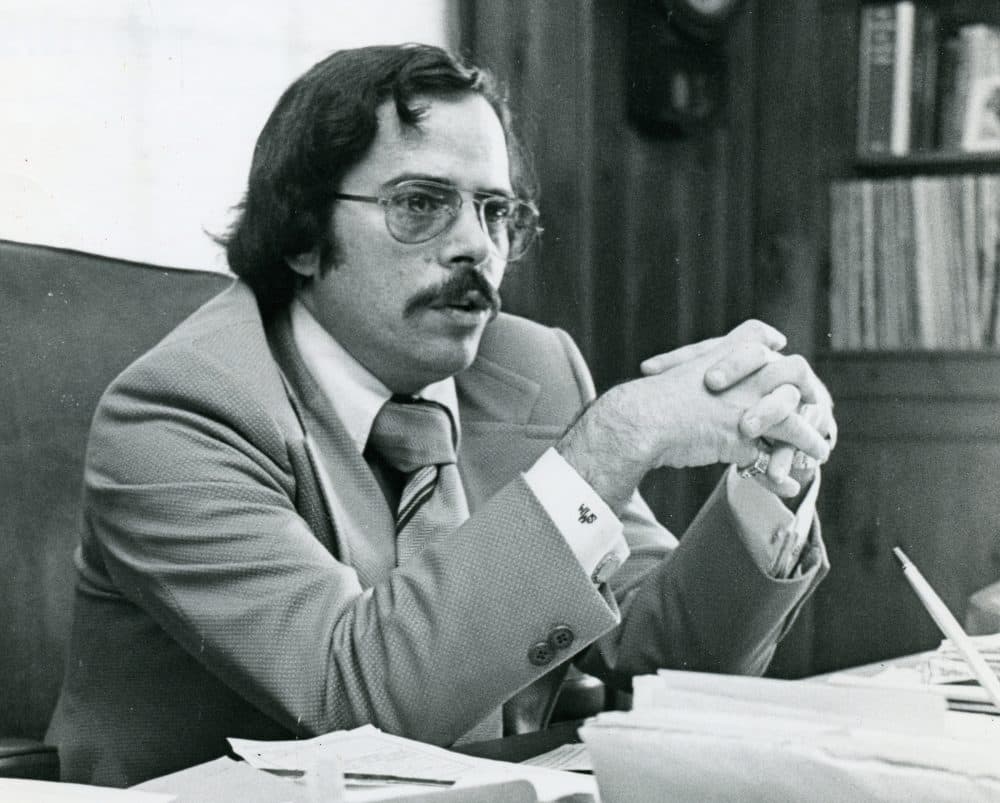

“Boston Phoenix Radio,” Stephen Mindich

The station was called “Boston Phoenix Radio” because it was part of the Phoenix Media Communications Group (PMCG) owned by Stephen Mindich, who founded alternative weekly The Boston Phoenix in 1972. Born in 1943, he grew up in the Bronx, graduated from Boston University’s School of Theatre in the College of Fine Arts in 1965 and earned a master’s from BU’s School of Public Communications in 1966, intending to be a theatre critic.

The Phoenix’s core demographic – college students and recent graduates – matched the station’s precisely. According to a November 2012 story in Boston magazine, however, Mindich’s son Brad said his father wasn’t sure whether to make WFNX a rock or a country station until very shortly before he launched WFNX. Brad, a teenager at the time, told him rock – specifically new rock, edgy rock, indie rock – was the best route.

Alt/Indie Rock Pioneer, Free Speech Champion, The Sunday Jazz Brunch

While ‘FNX promoted itself as “The East Coast’s First Alternative Rock Station,” the claim was debatable – even dismissible – given the plethora of commercial and college broadcasters up and down the eastern seaboard, particularly in New York City and Philadelphia. That said, the station led the charge in the alt-/indie-rock revolution on many occasions and consistently championed free speech.

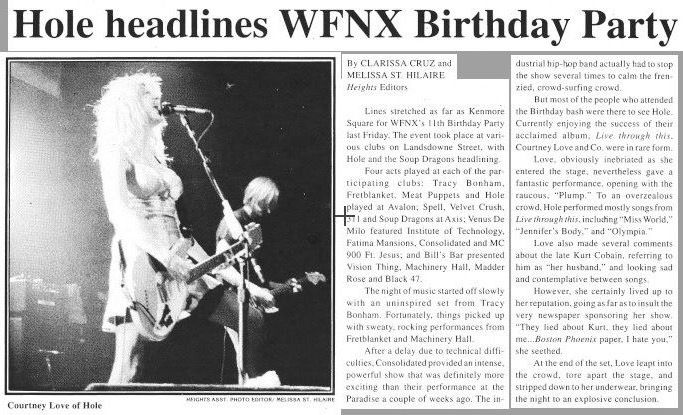

In 1991, for example, ‘FNX deejay Kurt St. Thomas gave Nirvana’s album Nevermind its world premiere, playing it from start to finish, and the station was the first in Boston to break other grunge acts like Pearl Jam, Oasis and Sonic Youth. It sponsored a number of musical events in the Boston area including the infamous Green Day concert in September 1994 at the Hatch Memorial Shell that ended in 20 minutes after a riot broke out.

In 1997, the station broadcast a live reading of Allen Ginsberg’s controversial 1956 poem Howl in its entirety, a direct violation of the FCC’s anti-obscenity laws; in a victory for First Amendment protections, the FCC didn’t file a suit against the station. When ‘FNX launched the talk show One in Ten in 1992, it became the first commercial station in the US to feature LGBTQIA content.

‘FNX also distinguished itself from competitors with its jazz programming, particularly The Sunday Jazz Brunch, hosted by Jeff Turton. For 26 years, from the station’s first week on air until May 2009, the show could be heard every Sunday from 6am to noon. Legendary jazz promoter Fred Taylor was deeply disappointed with the decision to cancel the program. “I think it shows WFNX’s total lack of acknowledgement of Boston’s arts community,” he said at the time. “To cut one lonely jazz show like this which represents a basic American art form from the station’s 24-7 programming is unconscionable.”

Notable On-Air Appearances

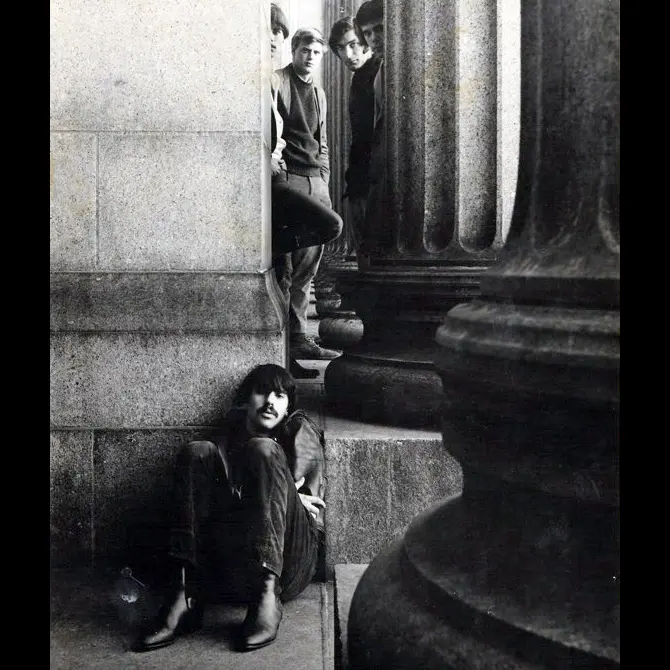

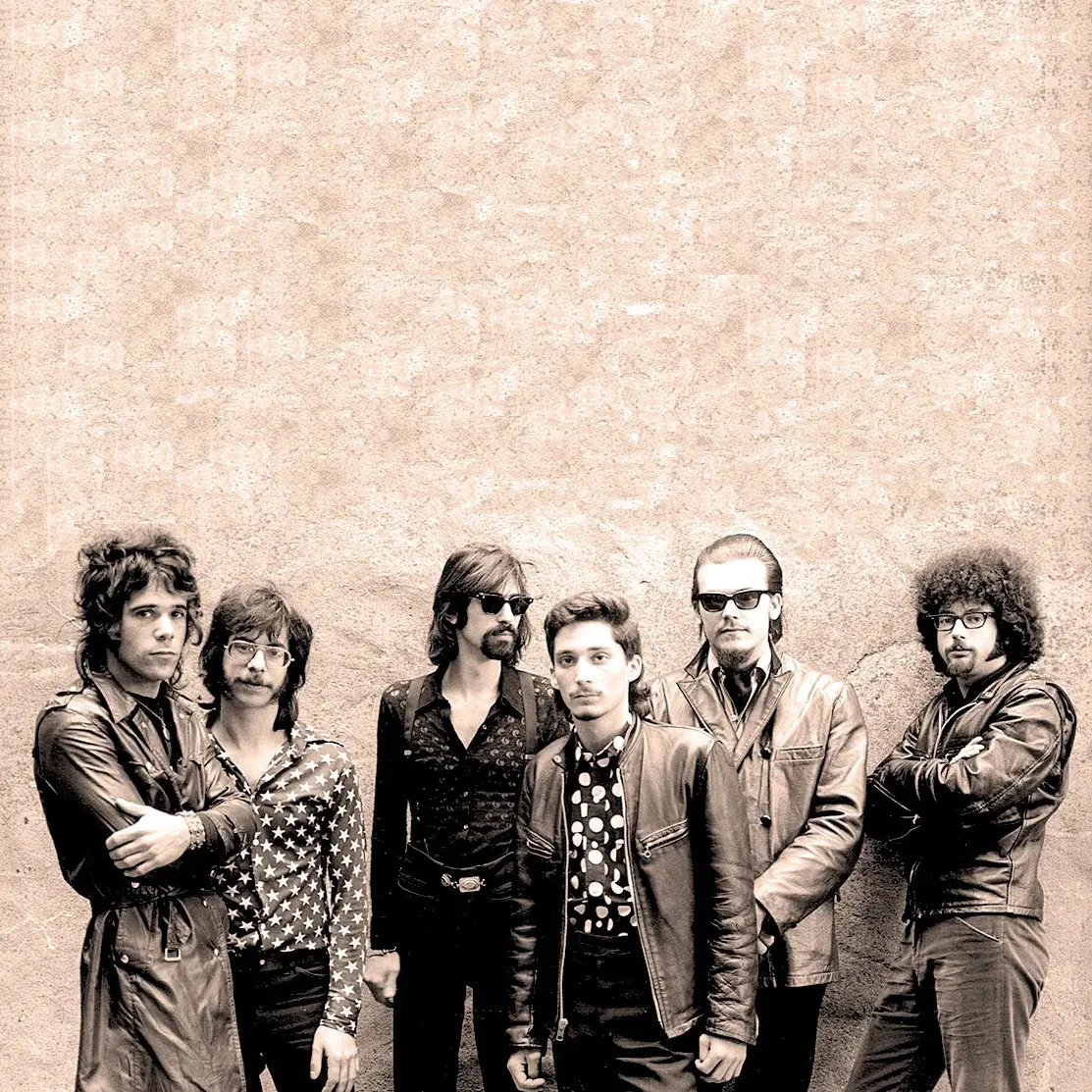

A parade of artists made on-air appearances at ‘FNX to be interviewed and/or perform a song or two. In 2018, deejay Julie Kramer displayed many of the photos she took of them at her exhibition “The Basement Archives: Vol. 1: The Ghosts of WFNX,” held at The Factory in Lynn, around the corner from ‘FNX’s former location.

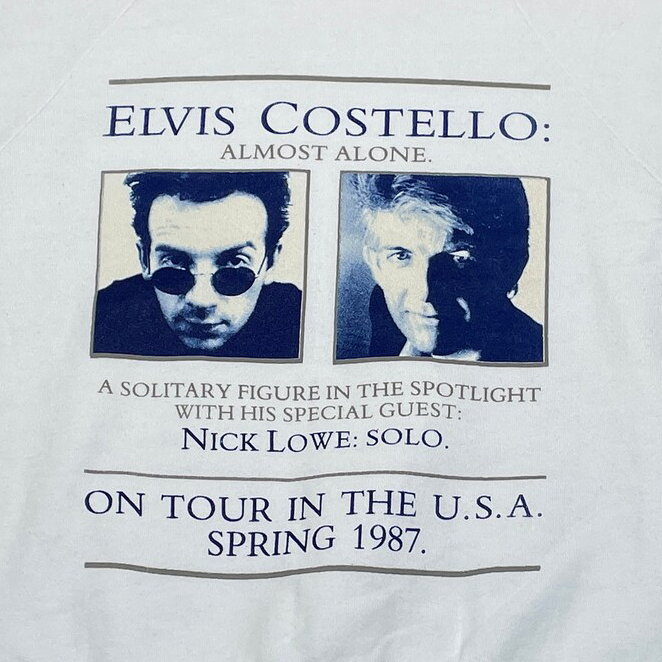

She said the first band she remembers photographing was the English roots-reggae group Steel Pulse around 1988. She went on to snap shots of Lenny Kravitz, Elvis Costello, The Clash’s Joe Strummer, The Boomtown Rats’ Bob Geldof, The Jam’s Paul Weller, Blondie’s Debbie Harry and Chris Stein, Hole’s Courtney Love and KISS’ Gene Simmons, among others.

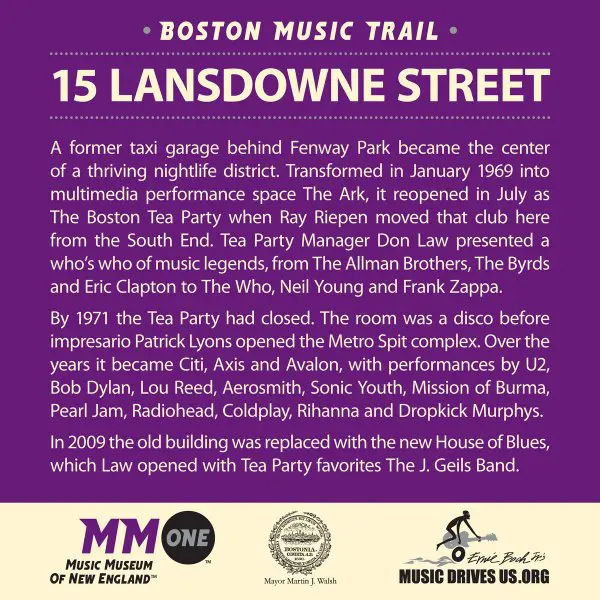

“Before playing The Channel or Bunratty’s, or Axis or Spit, musicians would always come to Lynn and they would hang,” she recalled to WGBH’s Henry Santoro (who hosted a jazz show on ‘FNX) in a 2018 interview. “We’d go to the Capitol Diner or we’d go to the beach or take a cruise around Nahant.”

WLYN-FM Acquisition, Signal Strength, Restrictions

Mindich purchased the station that became WFNX, WLYN-FM, in February 1983 from Puritan Broadcasting Service. That station was founded in 1963 and was a rock station (“Y-102”) starting in 1982, having broadcast Greek, Italian and country/western music prior to that. Basically, music, culture and nightlife aficionado Mindich saw an opportunity to use WLYN-FM’s new rock ‘n’ roll format to launch an on-air version of his alternative papers.

While WFNX’s 13,500-watt signal was just 25% as strong as WBCN’s 50,000-watt one, it was 50% stronger than WAAF’s 9,600-watter. In 1987, the station moved its transmitter from the WLYN-AM’s tower in Lynn to the former WEEI-FM/WBZ-TV tower above Malden Hospital to provide a better signal in the Boston area. FCC regulations prevented ‘FNX from broadcasting in the greater Boston area at more than 3,000 watts, however, because anything higher than that would interfere with other frequencies. This limited its listenership to the Lynn area and the North Shore; the station was essentially inaudible south of Dedham.

In 1998, ‘FNX’s Boston signal strength improved somewhat with the addition of a translator station, W267AI (101.3), atop Boston’s John Hancock Tower. In 2006, it improved dramatically when the FCC allowed the station to broadcast from a new transmitter and antenna atop One Financial Center in downtown Boston, at which time W267AI was deleted.

FNX Radio Network, Changing Media Landscape

Limited by FCC signal-strength restrictions in Massachusetts, in the late ‘90s Mindich’s PMCG expanded WFNX’s reach by acquiring stations in Maine, New Hampshire and Rhode Island, simulcasting them on what he billed the “FNX Radio Network.” In March 1999, the company purchased Sanford, Maine’s WCDQ-FM (92.1) and its AM sister station, WSME (1220). Later that year, PMCG bought WNHQ (92.1) in Peterborough, New Hampshire, and in March 2000 it acquired WWRX (103.7) in Westerly, Rhode Island.

But the regional power that the FNX Radio Network amassed in terrestrial broadcasting was no match for the Internet, which transformed the media landscape starting in the late ‘90s. By the early 2000s, deejays had lost much of the power they’d wielded for decades in terms of breaking and promoting new artists and their core audiences were shrinking by the week. Whereas stations like ‘FNX were once tastemakers, commercial pressure was such that following trends rather than setting them became the only viable commercial option.

Phoenix Struggles, Liquidation

To multiply the challenges the digital revolution brought about, by 2009 ‘FNX’s newsprint patron, The Boston Phoenix, was struggling to survive. After losing its most profitable revenue source, classified ads, to the Internet – as well as its virtual monopoly on the Boston media’s alternative ethos – the paper was slow in building a well-designed, profitable website, like thousands of other papers were. Mindich acknowledged to Boston magazine at the time that the Phoenix and ‘FNX had “cash-flow problems that resulted in some of our vendors not being paid on a timely basis,” noting PMCG was “no more immune” to the [2007/8] Great Recession than anybody else.”

In 2004, PMCG sold its Rhode Island station, WWRX, and in 2011 it sold its one in Maine, WPHX, a harbinger of the mass liquidation to come. With his back to the wall given the imminent collapse of the Phoenix, Mindich put all of his other broadcast licenses, including WFNX, up for sale in early 2012. On May 16 of that year, he announced that it was selling WFNX to Clear Channel Communications (later called iHeartMedia) for $14.5 million. The next day, he sold WFEX in New Hampshire to Blount Communications, which renamed it WDER.

Final Broadcast, Internet Station

Live programming ended on WFNX on July 20, 2012, the final song being the same as the first, The Cure’s “Let’s Go to Bed.” For the next four days, Clear Channel used 101.7 to broadcast a loop of The Standells’ “Dirty Water.”

On Halloween that year, Phoenix editor Carly Carioli and music editor Michael Marotta relaunched WFNX as an Internet radio station, playing the same mix of music as the old one. Most of the 13 full-time WFNX staff went to work for the Boston Globe’s online station RadioBDC and the ‘FNX stream ended in March 2013 when the Phoenix shuttered.

Clear Channel relaunched WFNX as WHBA, an adult-hits station branded as “101.7 The Harbor”; Aerosmith’s 1975 hit “Sweet Emotion” was the first song broadcast. In December 2012, WHBA relaunched as the EDM station “Evolution 101.7” and in January 2013 the call letters changed to WEDX.

Public Reaction

Within 48 hours of ‘FNX closing, Twitter, Facebook and Tumblr accounts under the name “Occupy WFNX” cropped up showing support for the station. “If it weren’t for WFNX, I wouldn’t have discovered a ton of bands both big and small because the station wasn’t afraid to take risks,” said Andrea, a then-34-year-old software engineer who started the Occupy WFNX accounts who said she lived in Medford but didn’t provide a last name.

Another Occupy WNX supporter using the name Fybush suggested that the station was a victim of its own programming. “One reason ’FNX probably didn’t do better is because of the number of college stations that take a similar approach,” he said, mentioning Emerson College’s WERS, MIT’s WMBR and Boston University’s WBUR.

Legacy

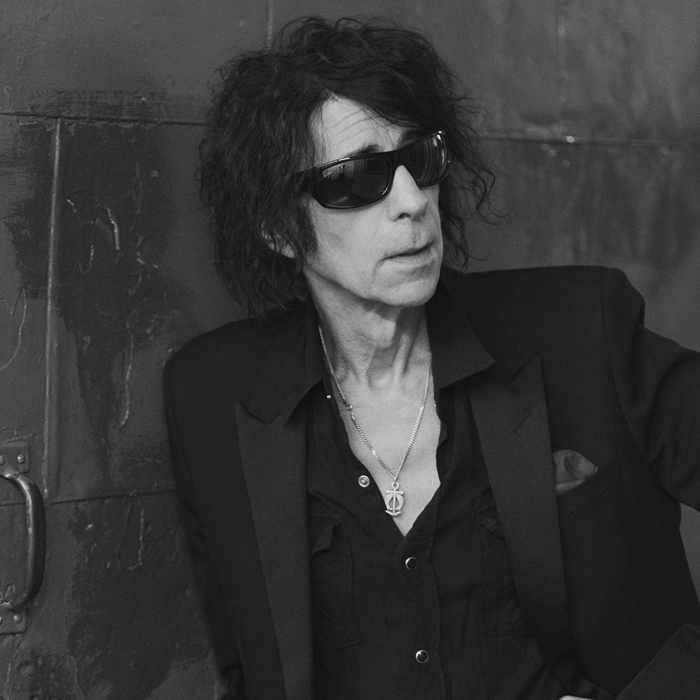

“The great thing about ’FNX was that it clearly knew what it was and what it wasn’t. Its aim was true and that’s unusual,” said Peter Wolf, WBCN’s first all-night deejay and former frontman of The Hallucinations and The J. Geils Band, in a 2012 interview with The Boston Globe.

Speaking to Boston magazine in 2012, deejay/photographer Kramer noted that there really is nothing quite like terrestrial radio. “I know you can listen to radio on the Internet. And I know you can download this and that. You can spend half your life on iTunes,” she said. “But when you’re driving in your car, and that awesome song comes on the radio, and someone’s talking about it being a beautiful day, and you roll down the windows, and the wind is blowing in your hair – there’s nothing else that feels like that.”

“The people at [satellite radio station] Sirius XM don’t know if it’s sunny or rainy outside your door,” she added. “But we do – or at least we did.”

(by D.S. Monahan)