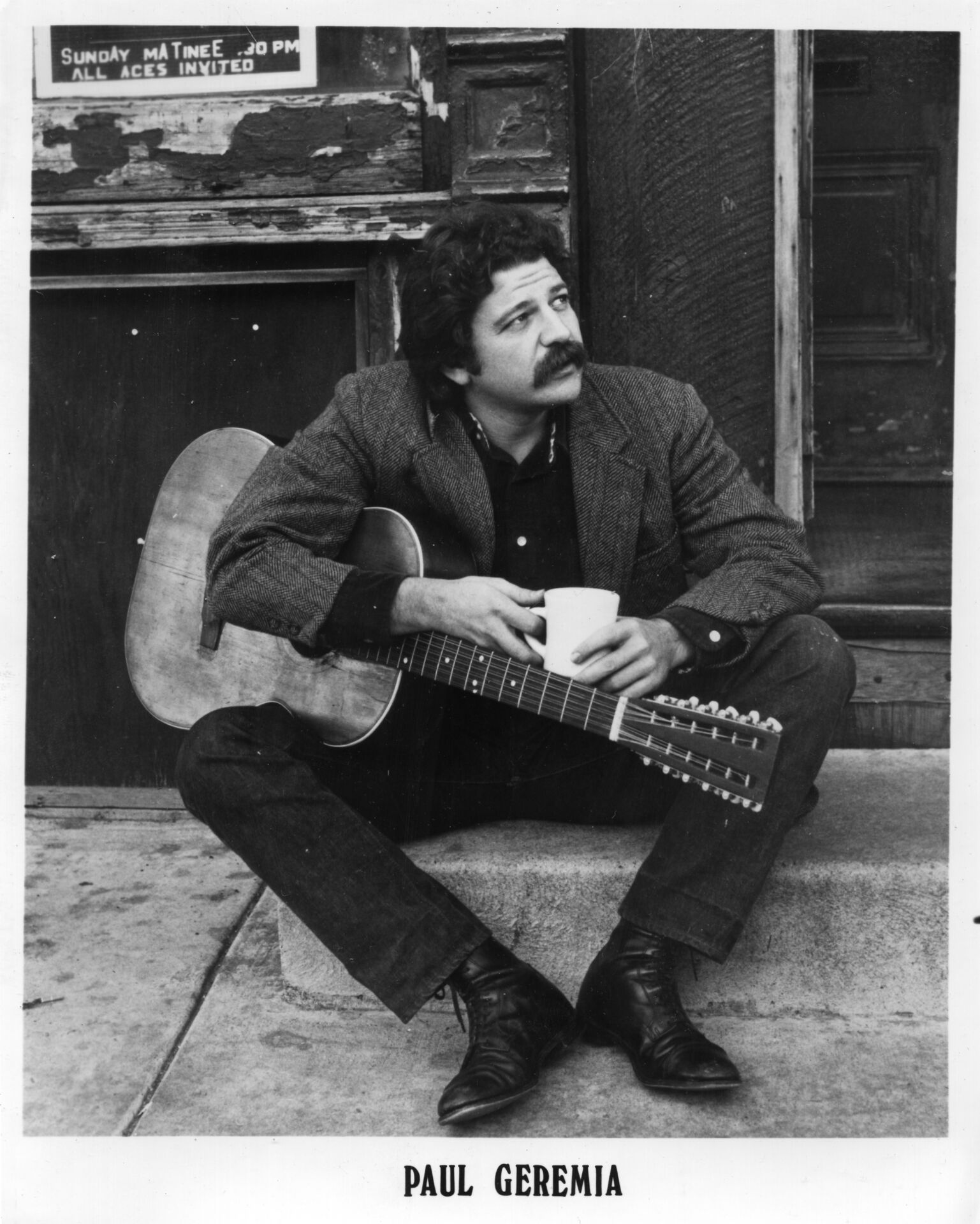

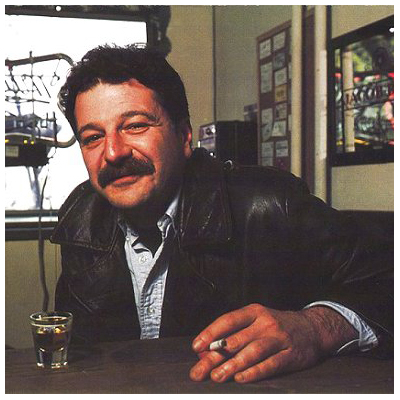

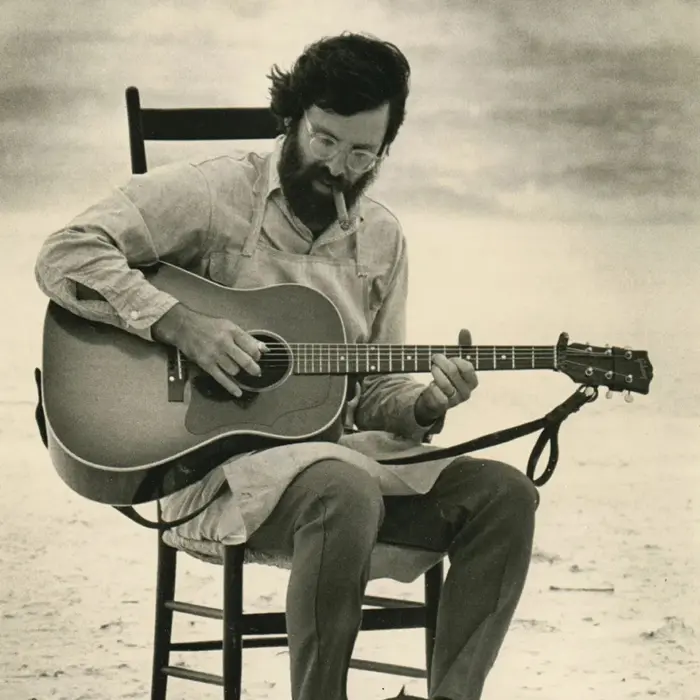

Paul Geremia

The word “troubadour” has morphed in meaning since it first entered the English language (around 1741, according to Merriam-Webster), originally referring to lyric poets between the 11th and 13th centuries but used most often today to describe traveling singers, particularly those of the folk genre.

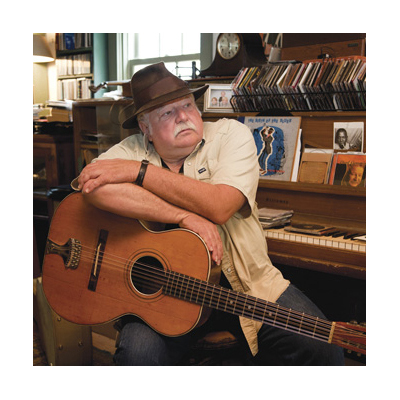

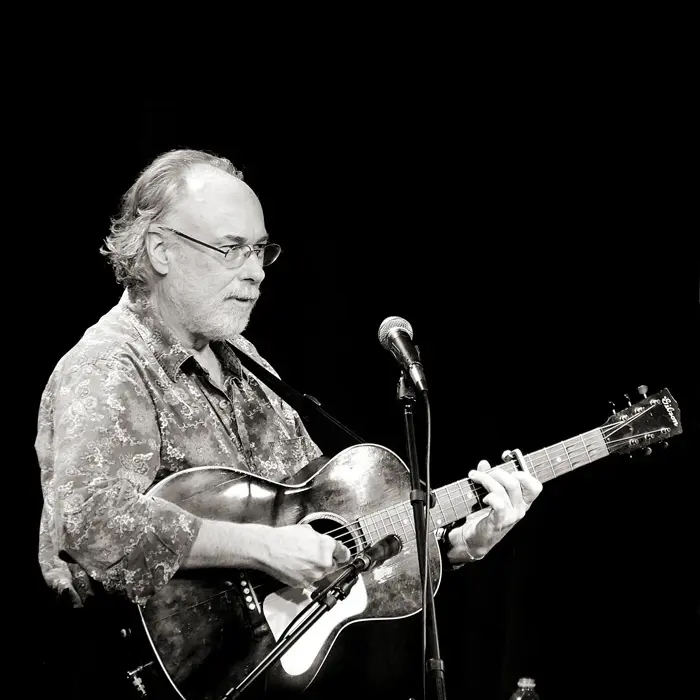

And when it comes to folk blues, Paul Geremia is the quintessential example of its modern meaning. If the New England Historical Society or any other organization ever offers a series of commemorative coins celebrating the most recognized and respected blues artists from the region, Geremia’s image should be embossed on one of the first ones minted.

OVERVIEW

Like other New England-based troubadours Tom Rush, Geoff Bartley and Taj Mahal, Geremia has cooked up a savory sonic stew all his own using ingredients provided by the iconic bluesmen who came before him, particularly Blind Lemon Jefferson, Robert Johnson, Blind Blake, Scrapper Blackwell and Blind Willie McTell, each of whose songs he’s covered live and on albums, most often McTell’s “Statesboro Blues.”

A scholar of pre-World War I blues in the same intensely focused way as Canned Heat co-founder Alan “Blind Owl” Wilson was, Geremia has recorded 11 LPs over 55 years – never playing an electric guitar on any of them – and Acoustic Guitar magazine has called him “possibly the greatest living performer of the East Coast and Texas fingerpicking and slide styles.” Known almost as much for his onstage humor and tales of the legendary blues artists he’s met as for his instrumental skills and the husk in his soulful voice, he was inducted into the Rhode Island Music Hall of Fame in 2013.

MUSICAL BEGINNINGS

Born on April 21, 1944 in Providence, Geremia has joked that his musical roots are “in the Providence River Delta” as opposed to the Mississippi Delta, though you’d never know it from the authenticity he’s exuded in every single musical move he’s made. A third-generation Italian-American, he spent his earliest years living in Silver Lake, then a predominantly Italian district of Providence, and his father’s job led to the family moving from Rhode Island to California and back twice before he turned six. Just before he began first grade, Geremia’s family settled in the town of Johnston, about nine miles outside Providence.

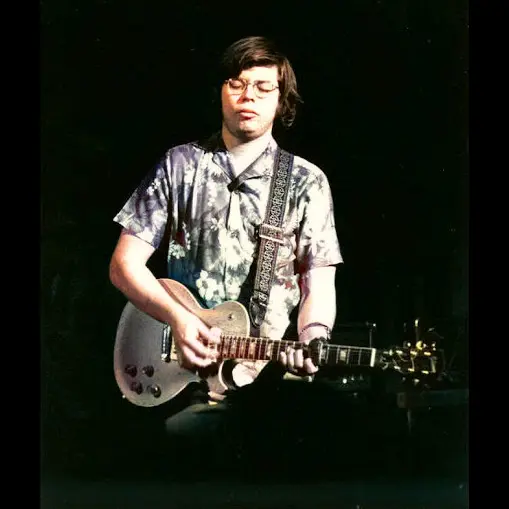

Geremia has said that his earliest musical memory is listening to opera on his grandfather’s wind-up record player at around age four. Though there was a piano in his family’s living room, he never played it and picked up the harmonica instead at age 12, wanting to emulate harmonica-playing movie cowboys and be able to hit the highest note Louis Armstrong played on his 1930 rendition of “St. Louis Blues.” At age 15, he began teaching himself how to play guitar using a Stella acoustic that his mother had given his father as a gift – and that his dad showed absolutely no interest in playing – and eventually worked his way up to a Harmony, a Framus, a Gibson Hummingbird and a Gibson J-200.

INFLUENCES

As a student at Providence’s Mount Pleasant High School from 1958 to 1962 – when the tidal wave called “rock ‘n’ roll” began crashing down so hard that major radio stations began changing from classical and jazz formats to a top-40 rock/pop one – Geremia has said he had no particular interest in the new genre except for some songs by Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley and Les Paul and Mary Ford. Even in 1960, when his schoolmates Vini Poncia and Peter Andreoli’s group The Videls had a hit with “Mister Lonely,” which went to #73 in the Billboard Hot 100, Geremia had no desire to “rock around the clock” with Bill Haley or “do the twist” with Fats Domino.

In addition to old-time blues artists, Geremia has credited steel guitarist Tony Poccia of Eddie Zack & the Hayloft Jamboree as a major inspiration. The stars of a national radio show on NBC that originated from Providence’s WJAR, the group pioneered the country-music scene in Rhode Island during the ‘40s and ‘50s, made dozens of recordings for Decca and Columbia and was inducted into the Rhode Island Hall of Fame in 2013 – the same year as Geremia.

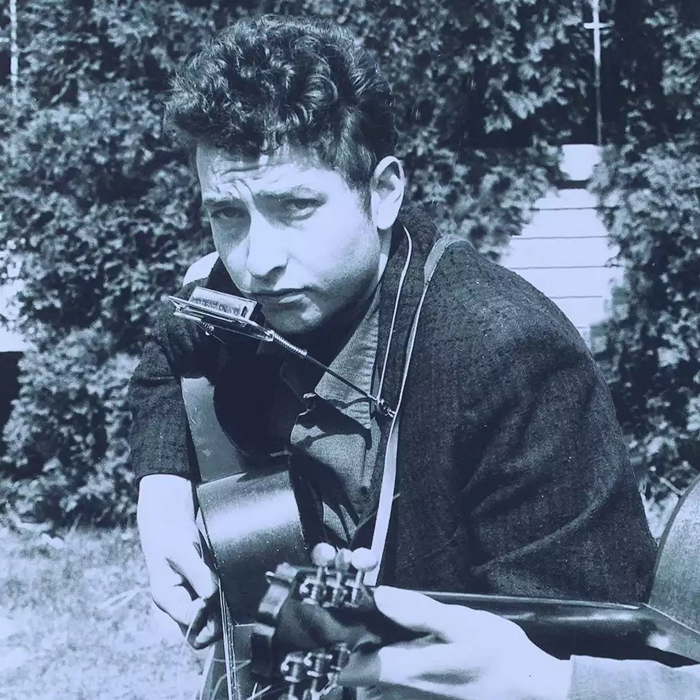

His lifelong passion for folk blues ignited in 1959 when he heard the seminal album The Country Blues, released that year by Folkways Records, and read the accompanying book. A 14-track collection of 78-rpm recordings compiled by music historian Samuel Charters, the LP had an immeasurable influence on the teenage Geremia – as it did on countless others of his generation including Bob Dylan and Dave Van Ronk – and prompted him to search for the original 78s, virtually all of which were out of print. After discovering that the best places for such rare discs were Salvation Army outlets, thrift stores and junk shops, he became a regular at Piedmont Furniture, a junk shop across the street from Classical and Central High Schools in Providence.

In 1963, a year after he enrolled at the University of Rhode Island (majoring in agriculture and playing in a folk trio), two events threw fuel on the fire that The Country Blues had sparked in him four years earlier: first, seeing up-and-coming singer-songwriter Tim Hardin at Club 47 in Cambridge; second, seeing Mississippi John Hurt at the Newport Folk Festival. Also at Newport that year was Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, who Geremia has credited as major influence on his own guitar style. “I really learned to fingerpick more from listening to Jack Elliott do ‘Railroad Bill’ than from anything else,” he once said. In 1965, Geremia dropped out of college to pursue music full time.

MOVE TO CAMBRIDGE, FOLKWAYS SIGNING, JUST ENOUGH, SIRE SIGNING

In 1966, at age 22, he put himself in the dead center of the folk map by moving to Cambridge and often traveled to Greenwich Village to play open-mic nights at the Folklore Center (owned by Izzy Young, who would be a pivotal figure in his near future). He played his first paid gig at Tete a Tete Coffeehouse in Providence and was soon playing at venues including Turk’s Head Coffeehouse, The Loft, The Sword In The Stone and the Unicorn Coffee House in Boston (where he ran the open-mic nights). In 1967, he made his first studio recordings, three of which appeared on an anthology of Rhode Island-based folk singers, Cracks in the Ceiling, on the Folk Arts label.

In 1968, Geremia landed a deal with Folkways Records after the label’s founder, Moses “Moe” Asch – who had recorded Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly – heard a tape WNYU had made of a Geremia performance, which Folklore Center owner Izzy Young had given him. The result was Just Enough, a 12-track collection of six originals and six covers that received strong reviews, with critic Bruce Eder noting Geremia’s enormous potential. “If more people had heard this record – and it had been done about three years earlier – he might have given Bob Dylan a run for his money as a serious acoustic folkie,” he wrote.

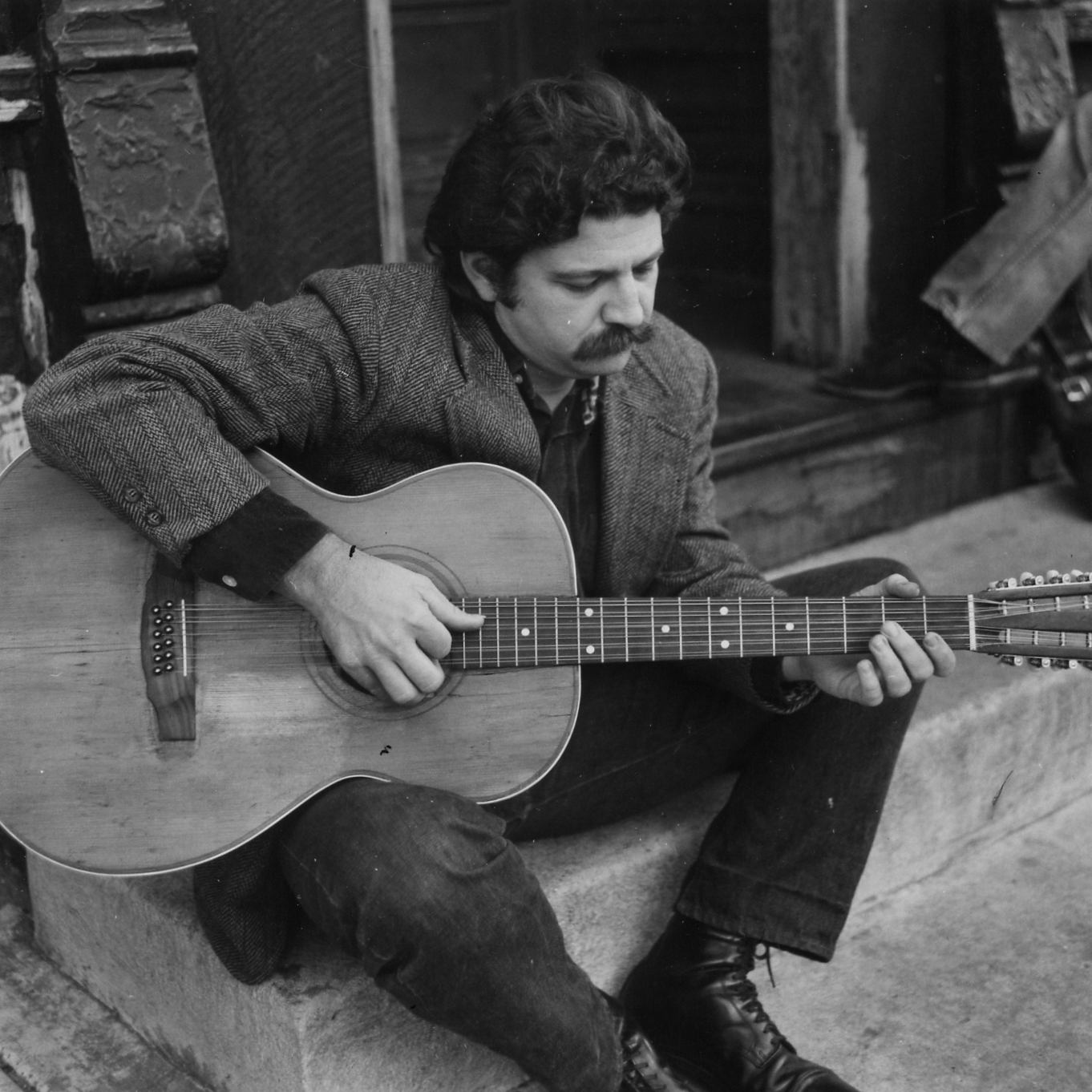

In 1969, he signed with Sire Records, which issued his sophomore album, a self-titled LP of 10 originals and one cover which sold reasonably well, particularly in New England, but not enough for Sire to continue his contract. By Thanksgiving that year, Geremia’s days as a guitar-slingin’, harp-wailin’ troubadour had begun in earnest, and he would tour relentlessly over the next 45 years, switching back and forth during concerts between his Gibson J-35 6-string and his converted 12-string Regal.

HELPING PINK ANDERSON

In 1973, Geremia helped resurrect the career of one of his musical heroes, Pink Anderson. In a meeting arranged by singer-songwriter Roy Book Binder, he visited the bluesman at his home in South Carolina and, after Anderson mentioned that he’d like to play “way up north” one day,” arranged a four-night stand for the 73-year old at the Salt Theatre in Newport. Anderson, who had never played in a nightclub before – nor to a white audience – went on to appear at Yale University, Harper College and the Folklore Center and died less than a year after his appearances at Salt.

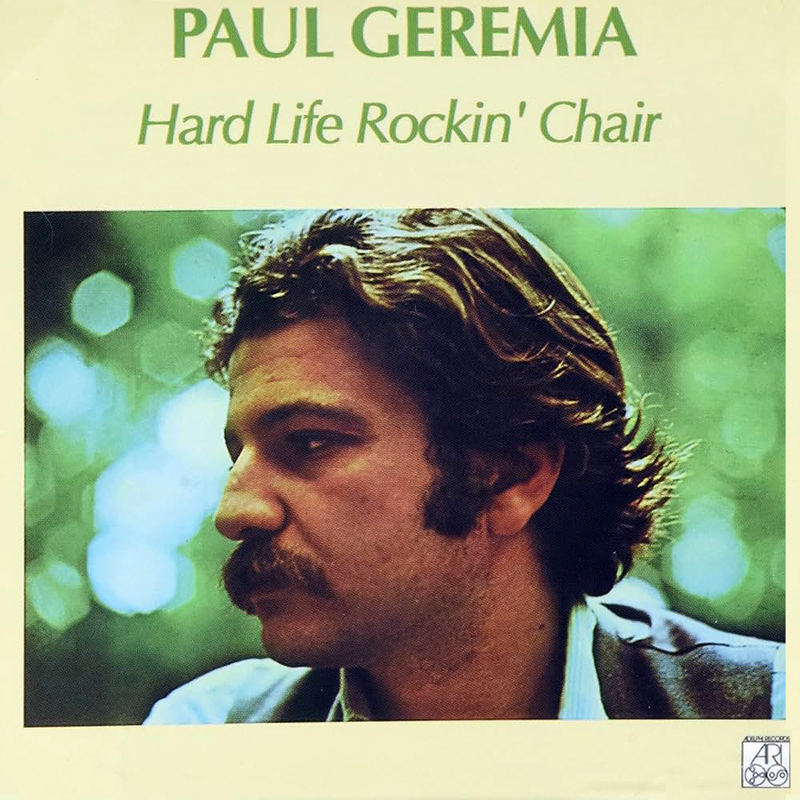

HARD LIFE ROCKIN’ CHAIR, I REALLY DON’T MIND, MY KINDA PLACE

Also in 1973, after signing with Adelphi Records, Geremia recorded Hard Life Rockin’ Chair. Five of its 14 songs were originals and the album sold better than his first two albums, but after recording a second LP for the label – still unreleased today, 50 years later – he left over disagreements about the promotional activities Adelphi demanded. After nine years without a label, he signed with Flying Fish Records in 1982 and recorded I Really Don’t Mind Living, followed by My Kinda Place in 1986.

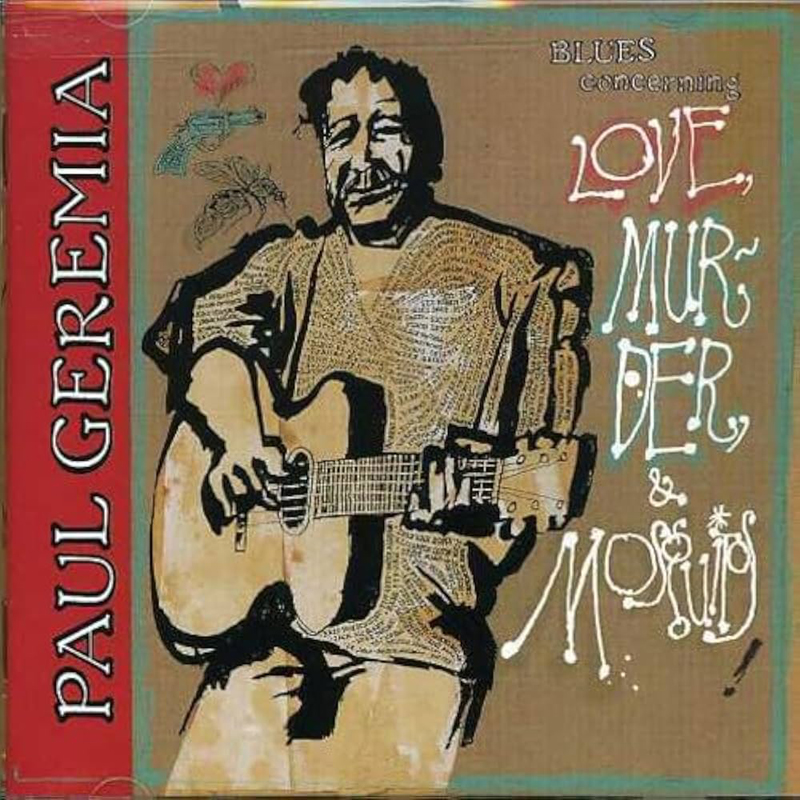

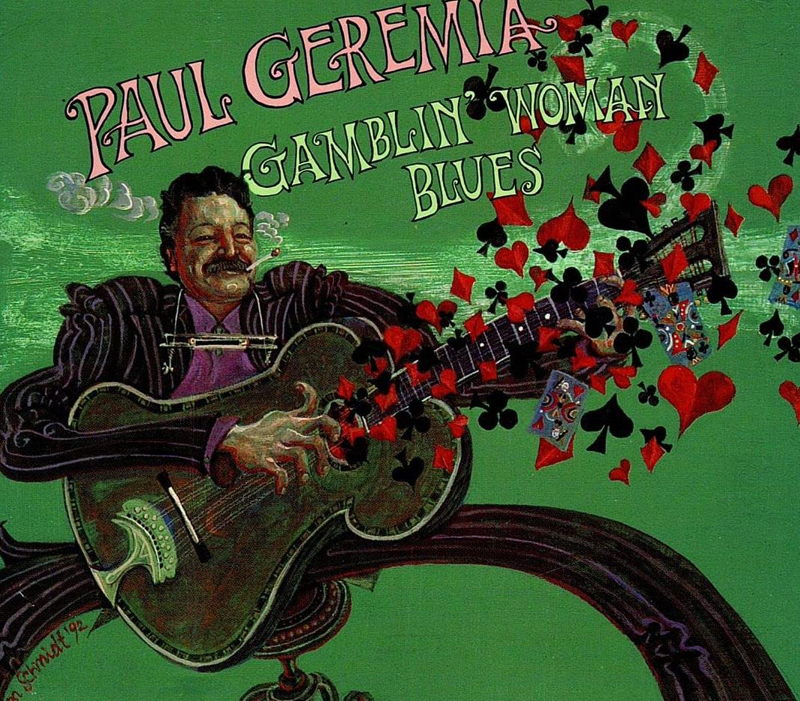

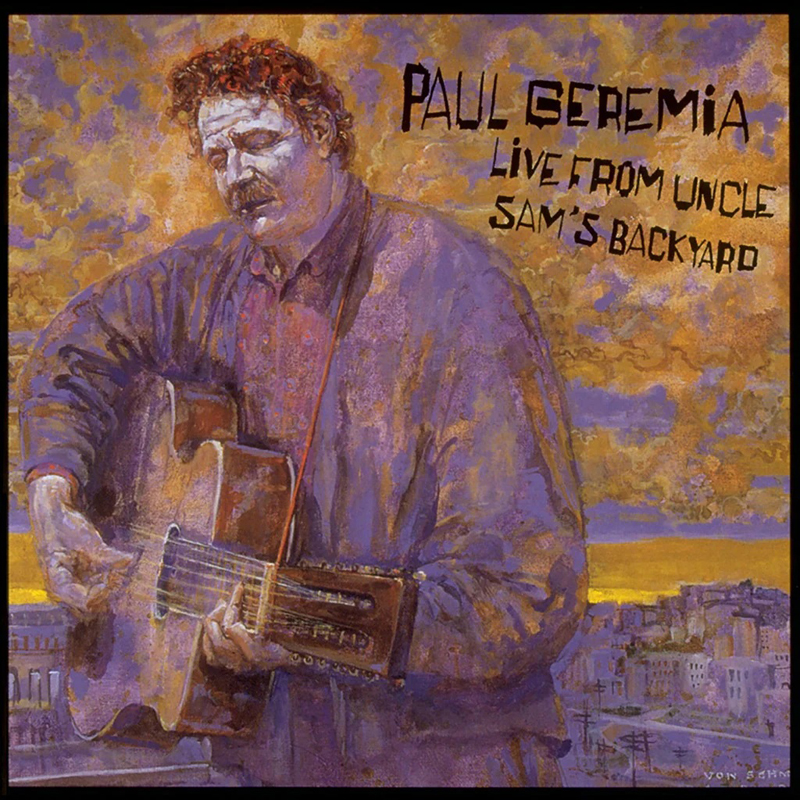

LATER ALBUMS, GRAMMY NOMINATION, DVD TUTORIAL

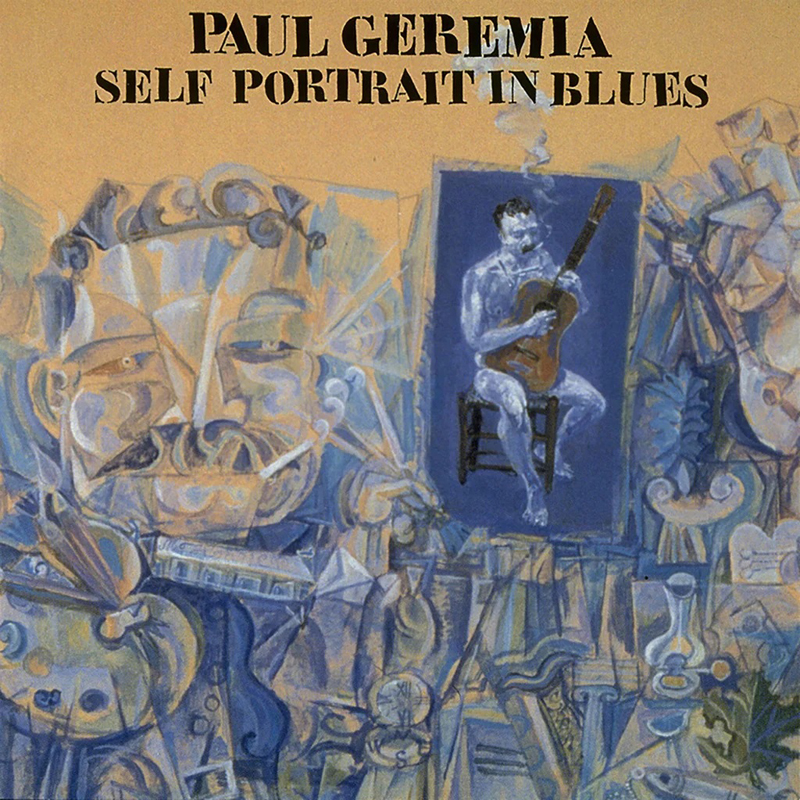

In 1989, Geremia played his first shows in Europe and continued to perform there regularly for the next 25 years. In the early ‘90s, he signed a two-album deal with Austrian folk-blues label Shamrock Records and his first Shamrock LP, Gamblin’ Woman Blues (1992), featured a painting by singer-songwriter Eric von Schmidt on its cover, as did three of Geremia’s future albums, all of which von Schmidt – a renowned painter and illustrator in addition to being an iconic folk artist – had made specifically for the albums.

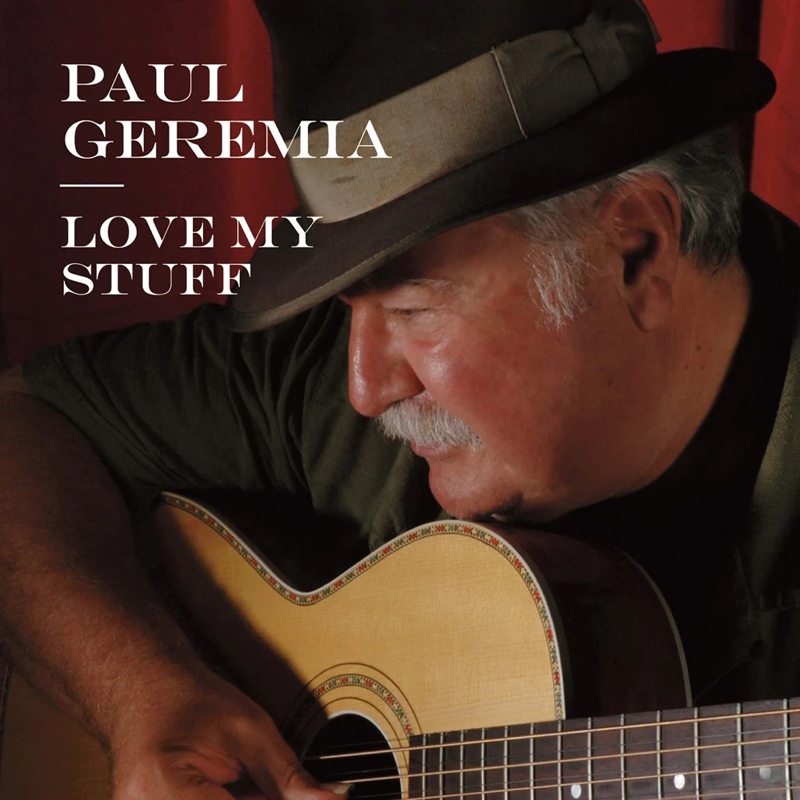

In 1993, Minneapolis-based Red House Records became the album’s distributor outside of Europe and in 1995, after Shamrock released the second album of his contract, Self Portrait In The Blues, Geremia signed with Red House. Four more albums followed, including his latest, Love My Stuff (2011), a 21-track LP featuring previously unreleased live performances cut between 1983 and 2007.

In 2002, Geremia’s rendition of the gospel standard “Get Right Church” from the Telarc-issued LP Preachin’ the Blues: The Music of Mississippi Fred McDowell was nominated for a Grammy. In 2008, the Stefan Grossman Guitar Workshop series produced the DVD Guitar Artistry of Paul Geremia: Six & Twelve String Blues in which Geremia gives tutorials on his own songs and his interpretations of others written by the bluesmen he admires most.

HEALTH PROBLEMS, LEGACY

In June 2014, Geremia suffered a serious stroke at age 70, ending his decades as the quintessential blues traveler. For the past several years, he’s been staying at Steere House Nursing & Rehabilitation Center in Providence and fellow musicians and other friends have rallied around the internationally renowned old-school troubadour with financial support to help defray expenses.

When asked in 2001 to comment on Geremia’s musical legacy, singer/songwriter John P. Hammond – son of John H. Hammond, the famed producer and Columbia Records executive who signed Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan – spoke for countless thousands of musicians and music lovers with the simplicity of his reply. “I’d drive a thousand miles to see Paul play,” he said.

(by D.S. Monahan)