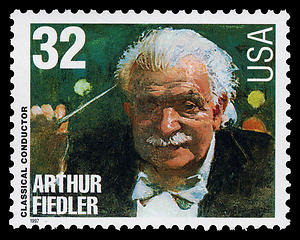

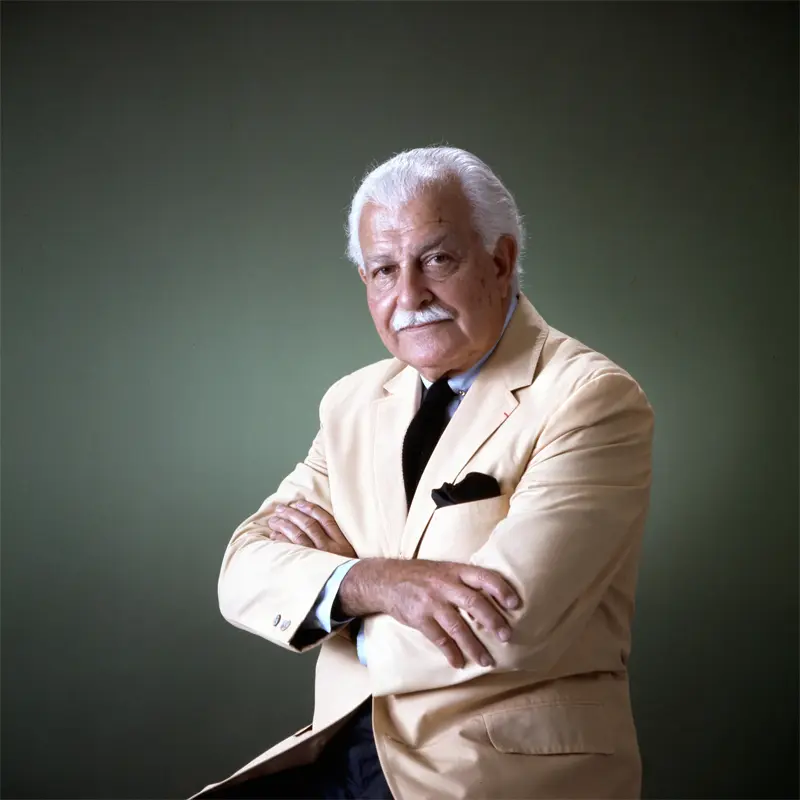

Arthur Fiedler

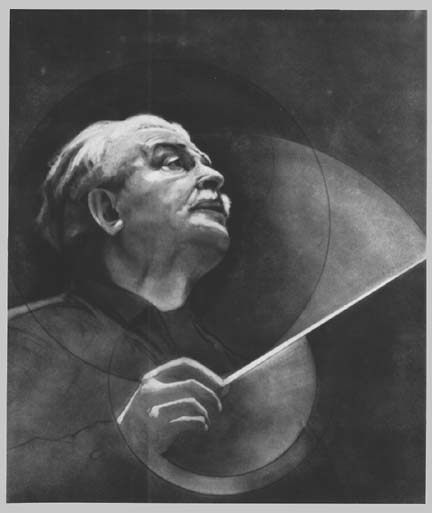

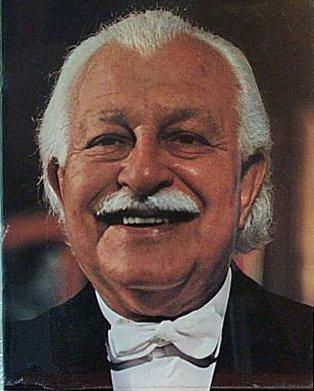

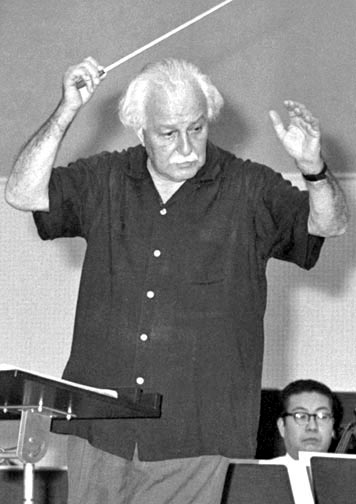

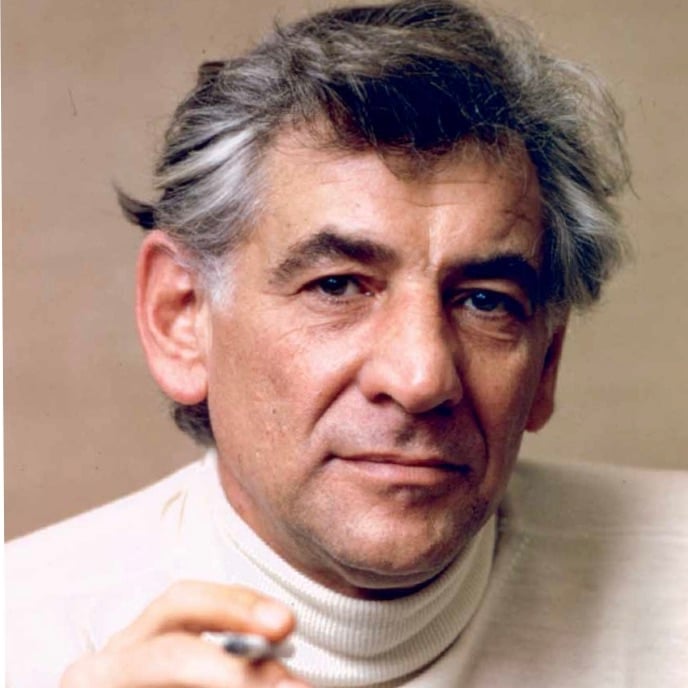

Appearances can be deceptive, but sometimes what you see is exactly what you get. For example, with his dashing good looks and impeccable style, Clark Gable really was the quintessential leading man; with his unruly hair and thick German accent, Albert Einstein really was quintessential scientific genius; with his 6’4” frame and boyish smile, Ted Williams really was the quintessential all-American ball player; and with his signature mustache and comically exaggerated gestures, Arthur Fiedler really was the quintessential orchestra conductor.

EARLY YEARS, BSO VIOLINIST, BSO CONDUCTING DEBUT

Born in Boston on December 17, 1894, a first-generation American whose parents were Austrian, Fiedler grew up in a thoroughly musical family, his father being a violist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) and his mother being a pianist. He was a student at Boston Latin School from age 13 to 16, and in 1900 his father retired and moved the family to Vienna. In 1910, they relocated to Berlin, where Fiedler studied violin at the Royal Academy of Music from 1911 to mid-1915.

In the fall of 1915, when World War I had begun to engulf Western Europe, 20-year-old Fiedler returned to Boston, following in his father’s footsteps by joining the BSO as a violinist while also working outside of the that orchestra as a pianist, organist and percussionist. His first time conducting the Boston Pops Orchestra (known as “the Pops,” an offshoot of the BSO founded in 1885) was in 1926, when he stood in as assistant conductor. His request to be appointed to the position full time was refused until four years later.

PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR, “EVENING AT POPS”

In 1930, Fiedler began his 49-year tenure as the orchestra’s first American-born principal conductor. Although the position is generally a mid-career phase, Fiedler immersed himself in the role for the rest of his life, working tirelessly to popularize symphonic music and the Pops across demographics through extensive recordings – the Pops have sold more albums than any orchestra in the world – and frequent radio and television broadcasts. Using his singular combination of musicianship and showmanship (and criticized by purists for editing some classical compositions to make them more palatable to non-afficionados), Fiedler established the Pops as one of the most respected orchestras in the world, becoming a musical icon in the Boston area, across New England and the greater US and around the globe.

One of Fiedler’s most enduring legacies is the series of free concerts that he initiated, called “Evening at Pops,” held at the Hatch Memorial Shell on the Esplanade, a public park along the Charles River. Contrary to popular belief, Fiedler began these performances six years before becoming the Pops’ conductor when, in 1924, he formed the Boston Sinfonietta, a chamber music orchestra comprised of BSO members that performed at the Hatch Memorial Shell in the summer. That ensemble performed at the first Fourth of July concert at the Hatch Memorial Shell in 1929, and the Pops have played there every Fourth of July since then except for in 2021 (when it was held at Tanglewood).

FOOTBRIDGE, BICENTENNIAL CONCERT, “HOLIDAY POPS”

In 1953, the Arthur Fiedler Footbridge opened near the Hatch Memorial Shell to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the free outdoor performances. In 1976, when the Pops’ Fourth of July concert was nationally televised for the bicentennial, the 80-year-old, jacketless Fiedler reached rock-star-level fame as he swung his arms above his head with abandon while conducting, swept up in the passion of the moment. Film of him puffing out his cheeks to the beat of the music provided one of the most unforgettable images of the country’s 200th birthday celebration.

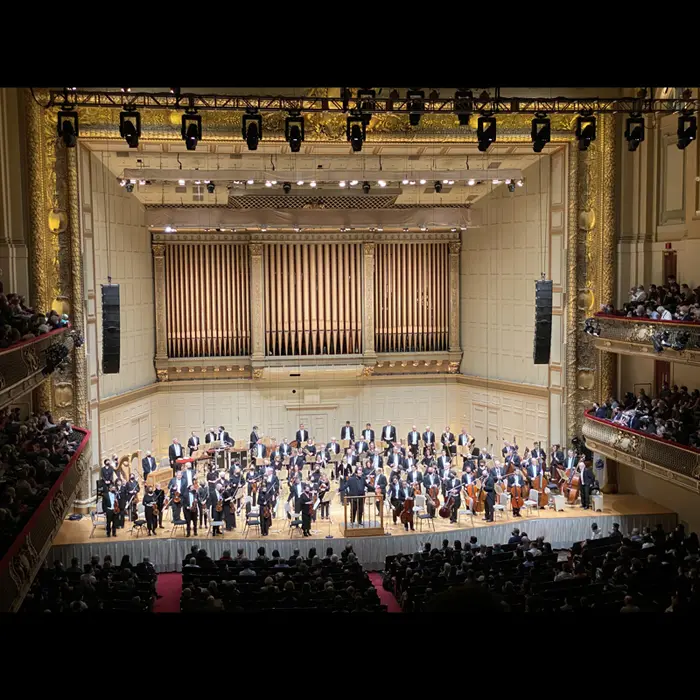

In 1973, Fiedler established another annual tradition, the Christmas concerts at Boston’s Symphony Hall known as “Holiday Pops.” The program features about 40 performances throughout December and, since the 1990s, a New Year’s Eve concert by the Boston Pops Swing Orchestra. Since 2014, the orchestra has been performing at showings of Christmas movies during Holiday Pops; the first one featured was Home Alone, for which the Pops’ Laureate Conductor John Williams wrote the score.

RECORDINGS, TELEVISION

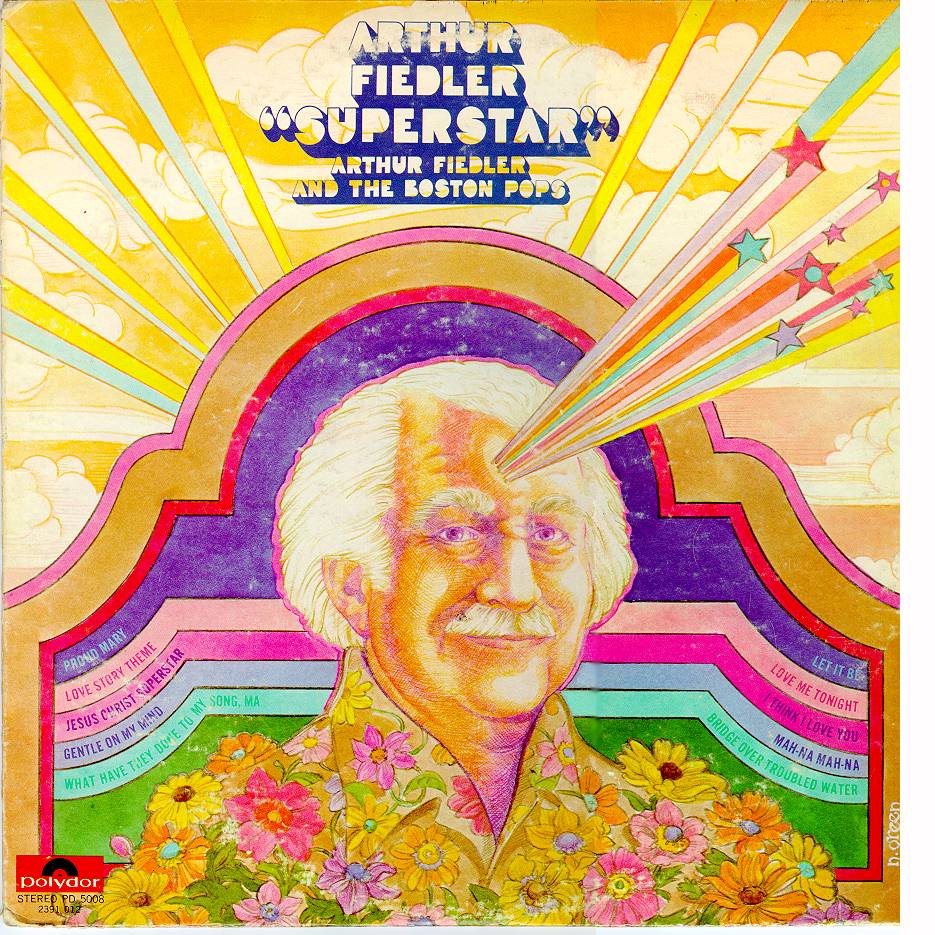

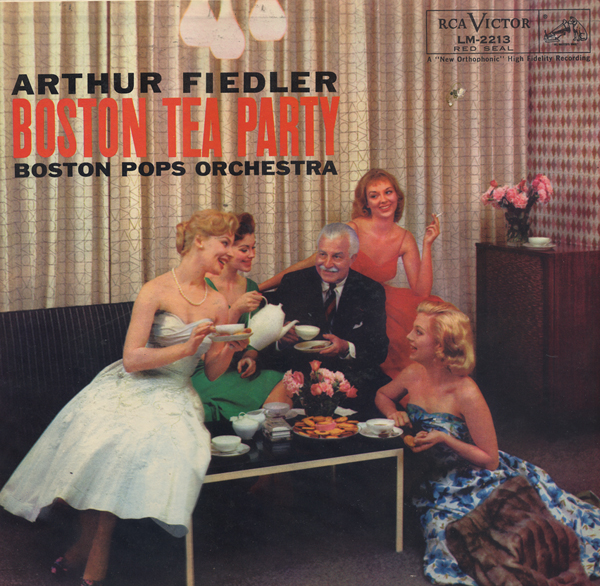

Fiedler’s other lasting legacies are in recording and television. Under his direction, the sales revenue from Pops’ recordings, including albums, singles and cassettes, exceeded $50 million. The orchestra’s debut album was issued in 1935 on the RCA Victor label, followed by its first high-fi recording in 1947 (RCA’s first long-playing classical album), which was re-recorded in stereo in 1954. Under Fiedler, a number of the Pops’ recordings were released as 45-rpm extended-play discs, beginning in 1949. Fiedler and the Pops recorded exclusively for RCA Victor until 1970, then switched to Deutsche Grammophon for classical albums and its partner company Polydor for pop-music releases before moving to London Records.

As for television, after making regular appearances conducting the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra on the NBC radio program The Standard Hour in the early 1950s, Fiedler introduced entire generations to classical music beginning in 1970 when, in association with PBS station WGBH-TV in Boston, he developed Evening at Pops, recorded during the regular season at Symphony Hall and broadcast weekly; the series continued until 2004, when the BSO stopped funding the almost $1 million/episode project. In 1971, he conducted at the nationally televised opening ceremonies for Walt Disney World.

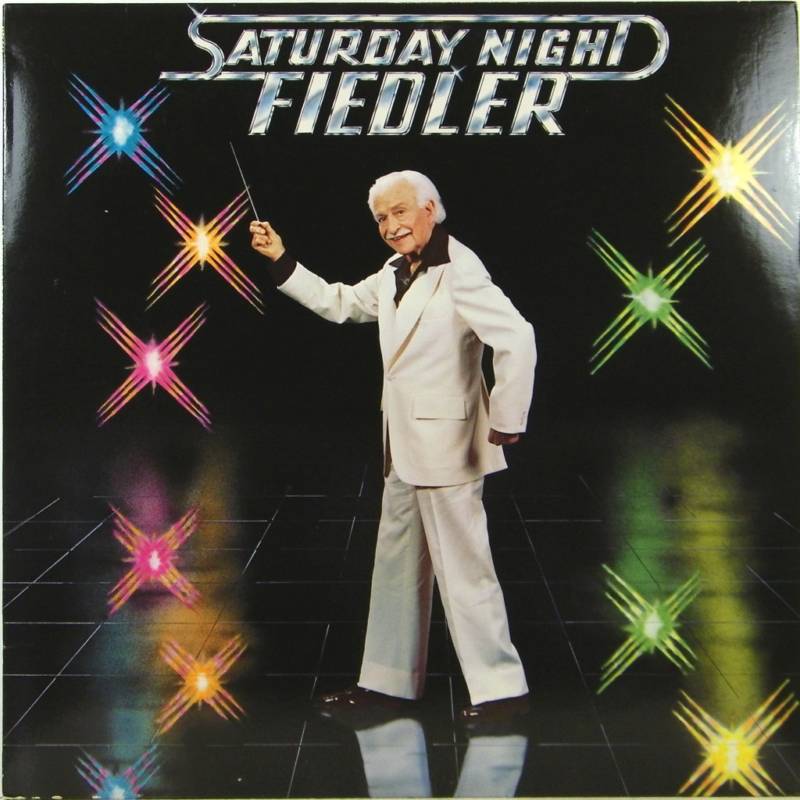

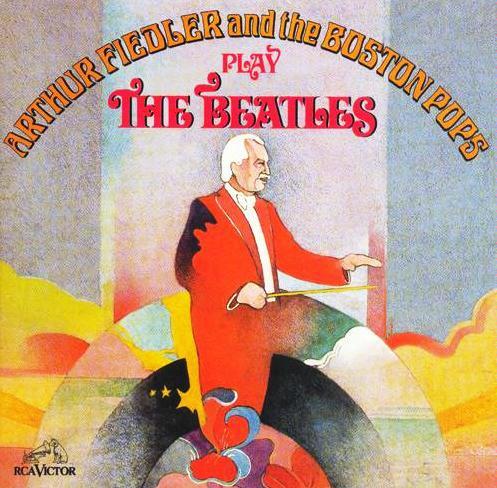

BROADWAY, HOLLYWOOD, THE BEATLES, SATURDAY NIGHT FIEDLER

Wanting to present the Pops as a “light” symphony orchestra and often using a self-mocking conducting style to attract larger audiences, Fiedler had the Pops perform and record music from notable Broadway shows and Hollywood films along with his arrangements of hits of the day, particularly those by The Beatles such as the on the 1971 album Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops Play the Beatles.

While the Pops occasionally recorded classical pieces that were not light in the least such as Dvorak’s “New World Symphony,” Fielder’s final album with the Pops was about as light as any orchestra has ever been: Devoted to disco and released in 1979, Saturday Night Fiedler featured his arrangements of songs from the 1978 blockbuster Saturday Night Fever.

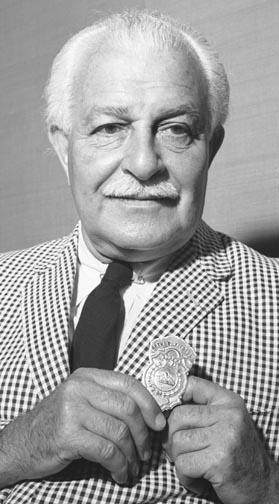

FIREFIGHTING FASCINATION, AWARDS, HEALTH PROBLEMS, DEATH

To his millions of fans, particularly those in New England, Fiedler was known for his fascination with the work of firefighters and for traveling in his own vehicle to see and/or assist extinguishing fires in and around Boston at any time day or night. In 1957, the Boston Fire Department made him First Honorary Fire Chief and several suburban fire departments gave him honorary helmets and/or badges. In Fiedler’s official biography, Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops (Houghton, Mifflin, Harcourt, 1981), author (and assistant BSO conductor) Harry Ellis Dickson writes that he assisted in rescue efforts at the Cocoanut Grove nightclub fire in Boston in November 1942, in which 492 people died.

Fielder received a slew of prestigious awards for his work with the Pops, including an honorary doctorate from the Berklee College of Music in 1972 and the University of Pennsylvania’s Glee Club Award of Merit in 1976 (given to those who have “made a significant contribution to the world of music and helped to create a climate in which our talents may find valid expression”). In January 1977, President Gerald R. Ford presented him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

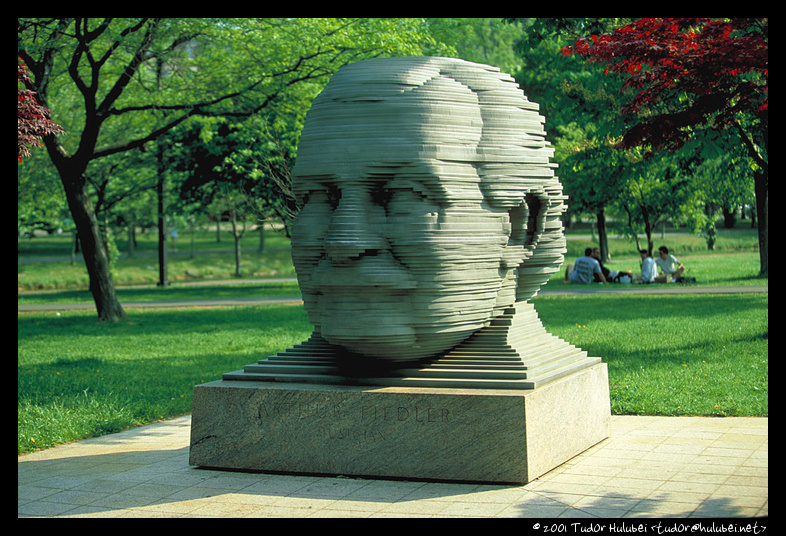

In 1979, after suffering congestive heart failure that resulted in brain surgery the year before, 84-year old Fiedler began his 50th season conducting the Pops on May 1, as scheduled, but was not well enough to conduct the Fourth of July event. Assistant conductor Harry Ellis Dickson led the orchestra in his place and Fiedler died six days later, on July 10, 1979. In 1984, the City of Boston honored him by placing an oversized bust of Fiedler alongside the Esplanade, the location of the free concert series that he spearheaded in 1924 and the first Fourth of July event that he conducted in 1929.

(by D.S. Monahan)