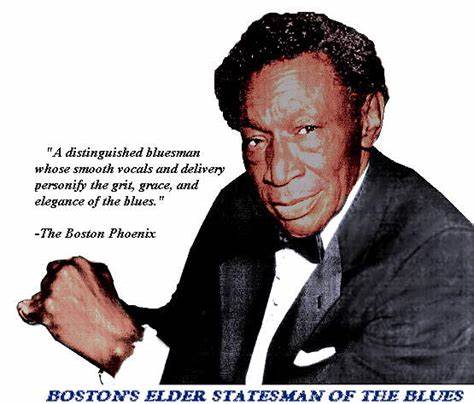

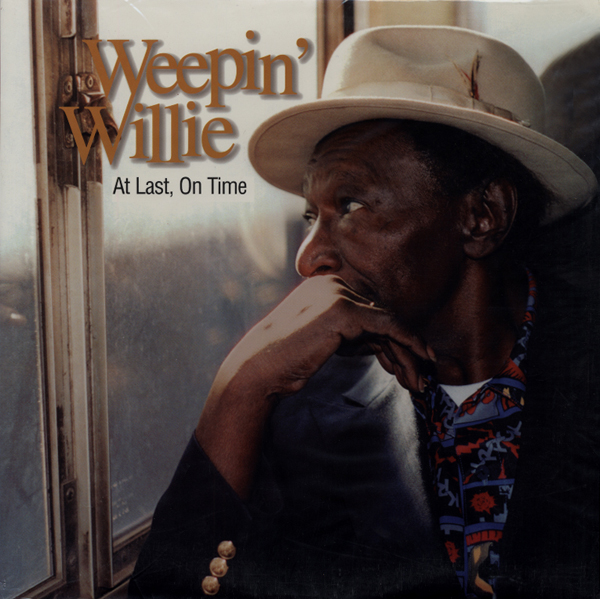

Weepin’ Willie Robinson

By the time Weepin’ Willie Robinson settled in Boston at age 33, he’d escaped the poverty of his childhood, served five years in the Army, been the emcee at a popular nightclub for over 10 years and opened for acts including B.B. King as a vocalist. Before then, he’d eked out a living as a field laborer, a dairy farm worker and a dishwasher (and at times a grifter and street hustler, Robinson’s friend and former WMFO-FM deejay Jim Carty told The Boston Herald in 2007).

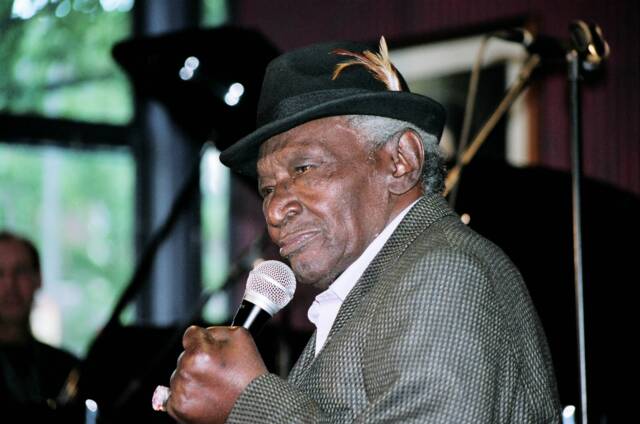

While that’s quite a success story by any measure, it’s no surprise that Robinson chose to sing the blues given the harsh realities of his hardscrabble upbringing, nor that he did so with such palpable passion. And given the indelible imprint he made on the blues scene his adoptive home city, it’s also no surprise that he was referred to as “Boston’s Elder Statesman of the Blues” despite having recorded only one album (in 1999, at age 73).

EARLY YEARS, MILITARY SERVICE

William Lorenzo Robinson was born in Atlanta, Georgia, on July 6, 1926, and spent most of his childhood as a migrant field worker, traveling up and down the East Coast with his parents picking cotton, tomatoes, potatoes and beans. His mother died when he was 10 and for the next five years he and his father traveled between Florida and Virginia looking for work in the fields; the Great Depression was in full swing, making opportunities scarce.

When Robinson was 15, his father sent him to Trenton, New Jersey, to live with a family friend, saying that he’d come to pick him a few weeks later. He didn’t, however, and Robinson never saw his father again. Parentless, stuck living in an unfamiliar state and functionally illiterate due to his lack of schooling, he took a menial job on a dairy farm before getting one as a dishwasher. In mid-1943, with his future looking bleak and World War II raging across Europe and the Asia-Pacific, 17-year-old Robinson convinced an Army recruiter that he was 18 and enlisted; he served stateside until 1948.

BECOMING EMCEE/VOCALIST, BECOMING “WEEPIN’ WILLIE”

Upon leaving the Army, 22-year-old Robinson returned to Trenton and landed a job as the emcee at a club that hosted blues icons like B.B. King, soul greats like Jackie Wilson and, starting in the early ‘50s, rock ‘n’ roll pioneers like Little Richard. The owner was impressed by his new hire’s knack for setting the right mood before performers took to the stage, particularly since he had absolutely no previous experience doing so, and Robinson soon became a star in his own right at the venue.

When the owner suggested that he adopt “Willie the Weeper” as a stage name (due to the natural bags Robinson had under his eyes), Robinson said he liked the idea but wanted to shorten it to “Weepin’ Willie”; the owner agreed and he used the name for the rest of his career. Some of Robinson’s friends and fans referred to him as “Willie Weep” over the decades, but he never billed himself as such.

Between 1948 and 1959, he warmed up audiences with comedic schtick for a laundry list of blues and R&B acts passing through Trenton, including singers Bobby Bland, Joe Turner, Titus Turner and Lloyd “Mr. Personality” Price. By the early ‘50s, Robinson had discovered his own natural talent as a vocalist and by the mid-‘50s he was singing with a combo led by Jimmy Tyler (previously the star saxophonist in Sabby Lewis’ orchestra) and other groups.

B.B. King was especially supportive of Robinson when he first started singing, urging him to keep practicing and to develop his own style. When Robinson explained that he knew only three songs – and that King had written them all – King offered a solution. “He told Willie that if he just memorized a set of songs, he’d work for the rest of his life,” WMFO’s Carty said in 2007. On one occasion, King unexpectedly invited Robinson to open for him and his 21-piece orchestra at the club in Trenton. “King used to hear him singing to himself and one night, when his opening act didn’t show up, he convinced Willie to sing on stage,” according to Carty. In later years, one of Robinson’s managers began calling him “the Dean Martin of the blues” because “like Martin, he wasn’t the greatest singer in the world, but he had that personality that could bring a song across.”

MOVE TO BOSTON

In 1959, the manager of Louie’s Lounge, a blues/R&B club in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood, saw Robinson singing with a group at the Trenton club when she was visiting the city. “She asked me if the band traveled and did we want to come to Boston,” Robinson told Ted Drozdowski of Boston magazine in 2006. “I said, ‘Yes,’ and she said, ‘Good. Be there on Monday.’ That was a Friday. Three days later we were in Boston, and I ain’t been back since.”

At the time, urban bluesmen were starting to draw sizable audiences and Boston had several blues/R&B clubs besides Louie’s Lounge; virtually every major act appeared in the city. “That’s when Roxbury was cookin’, you know,” he told Drozdowski. “You had Louie’s Lounge, Basin Street South, Big Jim’s Shanty. All those places were up along or right off Washington Street. They’re all gone now, but it was swingin’ back in them days. At Basin Street you had Count Basie and Redd Foxx. All the big stars in blues like B. B. King, Bobby Bland and Solomon Burke came into Louie’s Lounge.”

In the ‘60s, the Boston/Cambridge area’s abundance of college and university students and importance in the burgeoning folk scene made it a perfect stop for musicians of all varieties to find welcoming, open-minded audiences. And when it came to touring blues and R&B artists, Robinson frequently emceed, appeared as the opening act and sang with the headliners on stage at Louie’s Lounge, the Peppermint Lounge and other clubs. By the mid-’60s, thanks in large part to sportswriter-turned-promotor Dick Waterman, Boston was one of America’s top blues hubs and the ever-dapper, ever-charismatic Robinson essentially presided over the entire scene.

BUDDY JOHNSON, THE ALL-STAR BLUES BAND, AT LAST, ON TIME

Between the mid-‘60s and early 2000s, while working as emcee/vocalist at various Boston clubs, Robinson fronted several groups on a regular basis, among them The Buddy Johnson/Weepin’ Willie All-Star Band, which lasted until bassist Johnson’s death in 1998. After that, he formed Weepin’ Willie and the All-Star Blues Band, which at times featured saxophonists Emmett Simmons (of James Brown’s band), Gordon “Sax” Beadle (of Duke Robillard’s band) and Lynwood Cooke (of Luther “Guitar Jr.” Johnson’s band).

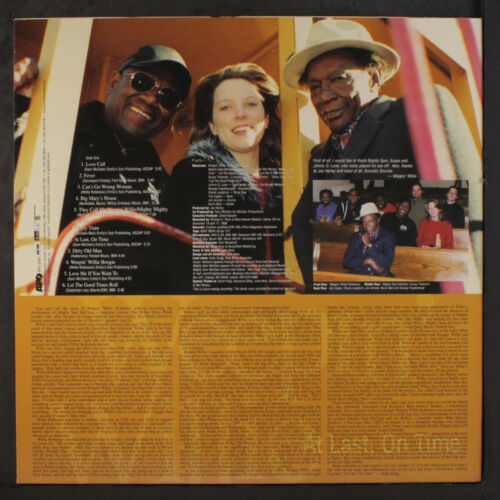

In 1998, Robinson signed with APO Records (his first-ever record deal) and cut his only album, At Last, On Time, which the label issued in 1999. Before then, the only recording of his that had been released was “Can’t Go Wrong,” which appeared on the 1991 Tone-Cool Records compilation Boston Blues Blast, Vol. 1. Co-produced by soul/blues singer-songwriter Mighty Sam McClain, the 11-track disc features Massachusetts native Susan Tedeschi on guitar and vocals on three songs. The album was a late-career triumph for Robinson and in 2000 the Blues Trust Foundation honored him with a Lifetime Achievement Award.

Hard times returned in 2005, however, when Robinson found himself homeless and out of touch with friends and family after he and his girlfriend broke up. “I walked the streets of Allston trying to find him,” said bluesman James Montgomery, a close friend of Robinson’s, in an interview with The Boston Herald in 2007. “His clothes were in paper bags.” After that, blues artists held a benefit concert, made sure that Robinson was fed, clothed and safe, and the singer/emcee’s life turned around.

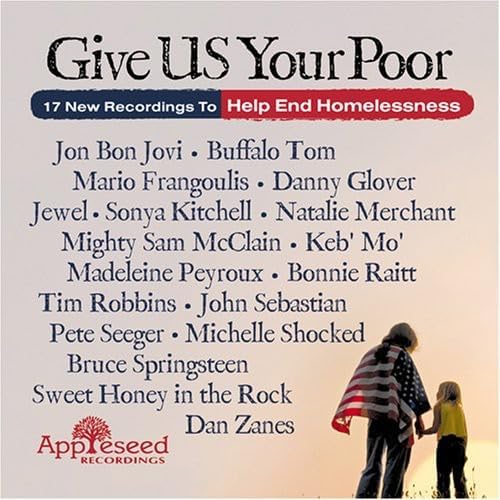

Robinson was the first recipient of a grant from UMass Boston’s Give Us Your Poor organization, recorded the song “Walking the Dog” with Bonnie Raitt for the benefit album Give Us Your Poor (Appleseed Recordings, 2007) and WMFO’s Carty arranged for him to live at the Mount Pleasant Home in Boston’s Jamaica Plain neighborhood, where he was something of a resident celebrity. For the next few years, he performed in and around Boston, on Cape Cod and at the Mount Pleasant Home, where he played his last show on Christmas Day 2007 (with James Montgomery).

DEATH, LEGACY

Robinson died five days after that Christmas appearance, on December 30, 2007, in a fire started by a cigarette he was smoking in bed, according to the Boston Fire Department. “The death of Weepin’ Willie Robinson in a nursing home fire early Sunday morning in Jamaica Plain was a tragic demise for the 81-year-old blues singer,” wrote Andy Gewertz in an obituary for The Boston Herald. “And yet the past two years of Robinson’s life have to count as both a comfort and a triumph.”

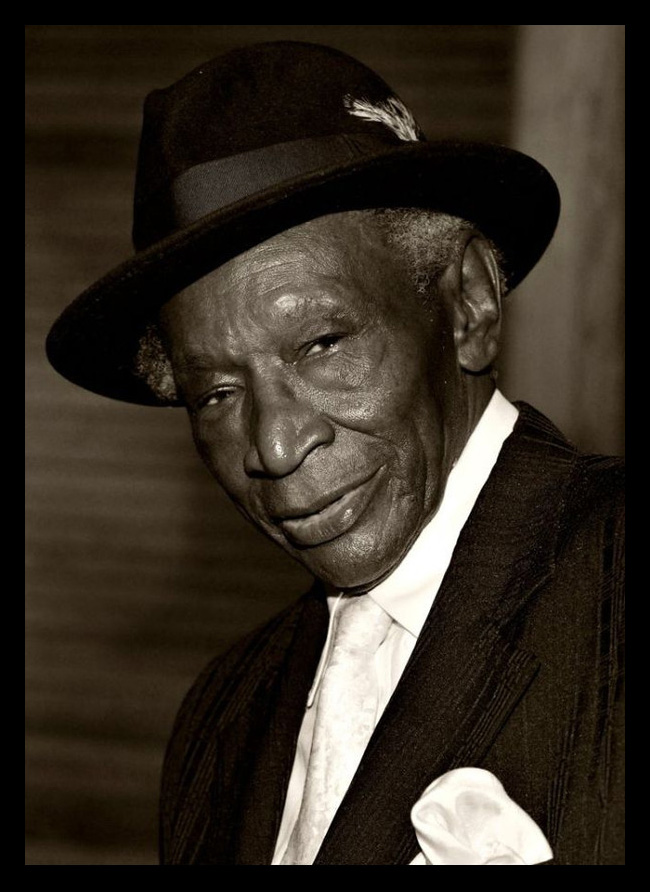

In the weeks following his death, tributes poured in from blues artists, media figures and fans alike. “He was truly the elder statesman of the blues. He was our godfather. He was the most gracious, loving man,” said Holly Harris, host of Blues on Sunday on WBOS. WMFO’s Carty commented on Robinson’s voice, saying that it never lost its luster. “The timbre never degraded,” he said, “even with all his smoking and drinking.” Montgomery mentioned the uniqueness of his vocal style and the resilience of the man himself. “Like Muddy Waters, he had a clear, identifiable voice,” he said. “Even if he was in pain from arthritis, he got into a zone vocally, with a lot of feeling and no cliches.”

Lorraine Robinson, Robinson’s daughter, told The Boston Globe that her father was always able to find peace on stage no matter what struggles he was facing in his life. “A great smile would come on his face and he would be in his own little world, like he’d tune everything out,” she said. “He just felt the music. It was so much in his soul.”

(by D.S. Monahan)