Sabby Lewis

While few people today think about an announcer’s race, virtually all American radio announcers were white in the first half of the 20th century. The US was largely segregated – officially by Jim Crow laws in the South and unofficially by institutional barriers in the North – and although well-known Black musicians were hired to perform popular songs on air, few (if any) radio stations would employ a Black announcer. One of the people who helped change that racial imbalance in Boston was William Sebastian “Sabby” Lewis.

Musical beginnings, Move to Boston

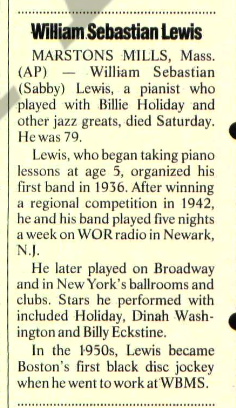

Lewis never expected to be a trailblazer. Born in Middleburg, North Carolina, in 1914, he grew up in Philadelphia and began taking piano lessons at a young age because his mother wanted him to. He resisted at first, but eventually he enjoyed it and it was a great way to entertain his friends. By the time he was in his teens, he’d decided on a career in music which, as it turned out, was a very wise choice.

Around 1932, Lewis’ family relocated to greater Boston; he studied piano at the then-Boston Conservatory (now Boston Conservatory at Berklee) and in 1936 he assembled his first group, an eight-piece jazz band. Newspaper listings showed that he was soon performing all over eastern Massachusetts and New Hampshire and by the late 1930s, he was receiving excellent reviews.

Early performances, Decca signing

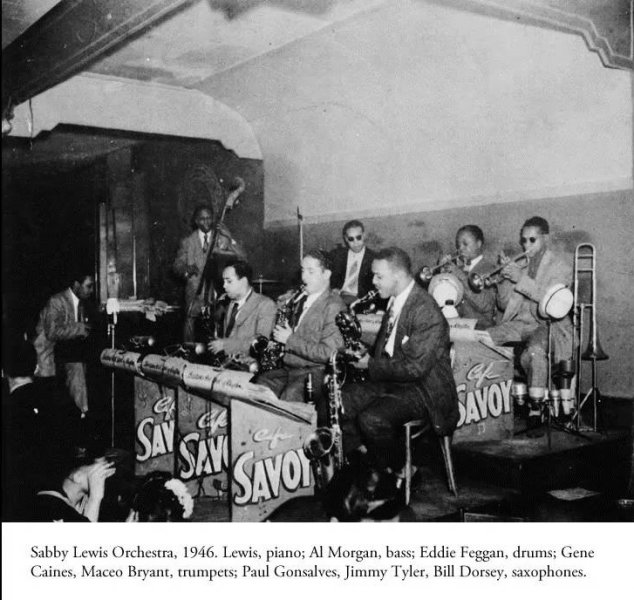

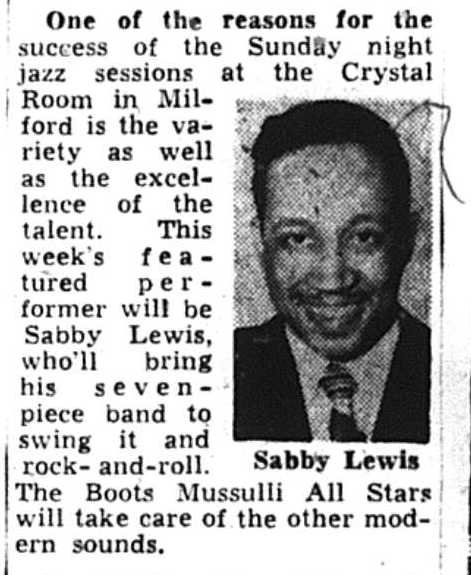

Boston didn’t boast as big a club scene as New York City, but that didn’t mean there weren’t some excellent venues for jazz and other dance music. Lewis and his band played in most of ones in the Boston and the surrounding area, but in the early 1940s they performed most frequently at the Savoy Café, which was located at 410 Massachusetts Avenue, near Huntington Avenue. They gained a following in New York City, too, by playing at clubs such as The Famous Door and Kelly’s Stables.

In the spring of 1942, Lewis and his orchestra signed with Decca Records but due to a ban on making records – partly to conserve shellac during the war but mostly due to a strike by the American Federation of Musicians over royalties – all commercial recording was curtailed in the US from August 1942 through November 1944.

The Fitch Bandwagon

Although Lewis couldn’t make any records for over two years, something was about to happen that would boost his popularity exponentially. There was a highly rated Sunday night program on the NBC Radio Network called The Fitch Bandwagon (sponsored by the F.W. Fitch Company, known for its shampoo and other beauty products) and, since its debut in 1938, it had showcased some of the top American bands and vocalists. In addition to the big names, the show also visited various cities in search of up-and-coming acts.

In the summer of 1942, the program came to Boston in looking for local talent. Fans were invited to fill out ballots and vote for their favorite band; whoever got the most votes would earn the chance to perform on The Fitch Bandwagon, an amazing opportunity given that this show was heard on stations from coast to coast. More than 100 local bands sought the public’s support and when the votes were tallied, Sabby and his orchestra received the most – a total of 7,286. As a result, the Sabby Lewis band was heard live on WBZ in Boston on July 19th, along with other NBC affiliates nation-wide.

New York City, Savoy Café, The Hi-Hat, First recordings

More gigs in better-known venues came Lewis’ way literally overnight. In September 1942, he was booked into New York City’s famed Savoy Ballroom and soon afterward New York’s WOR gave him his own program several nights a week. He also appeared on the Mutual Broadcasting network occasionally and whenever he and his band performed on radio, Lewis introduced the selections himself.

Throughout the 1940s, Lewis’ popularity continued to grow. Audiences found his music so danceable that they wanted him and the band to stay on long after their stage time has expired. As one New York newspaper noted, Lewis’ orchestra became particularly famous for playing long engagements: in the Big Apple, they performed at the Zanzibar for seven months straight, at Kelly’s Stables for 16 weeks straight and at The Famous Door for 10 weeks. When they returned to Boston, they spent nearly four years as the main attraction at the Savoy Café.

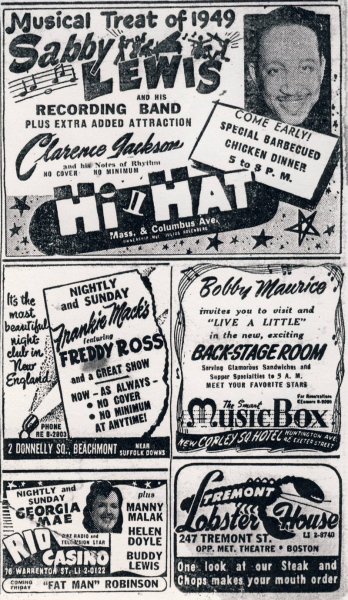

By the late 1940s, however, Lewis and his band had settled into a different Boston club, The Hi-Hat on Columbus Avenue in the South End. Finally, he was able to put out some recordings, including “I Made Up My Mind,” “Bottoms Up,” “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love” and “The King,” all of which saw favorable reviews from music-industry trade publications. Several of these recordings were on the Mercury label.

The rise of radio

Meanwhile, radio (and popular music) were gradually changing. Where radio shows had previously been live and many stations employed their own in-studio orchestras, by the late 1940s stations were trying to save money by playing more phonograph records and less live music. This led to a new occupation, the “disc jockey” (soon shortened to “deejay”), meaning someone who chatted on the air while playing records instead of being a formal “announcer” who spoke with perfect diction while introducing bands. Disc jockeys used a new style of talking to listeners, appealing to a young audience by being up-beat, talking at a natural speed and using the slang of the day.

In Boston, several new radio stations went on the air after the war ended, among them WBMS at 1090 AM; the call letters stood for “World’s Best Music Station and the station played classical music. When classical’s popularity began to ebb in the early ‘50s, the station moved to middle-of-the-road pop and briefly its changed call letters to WHEE (in 1951).

Becoming a deejay

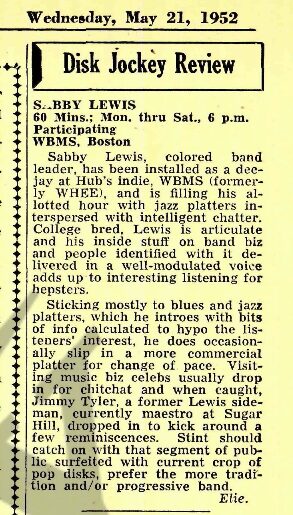

In early 1952, new station manager Norman Furman, made major changes. WBMS put a variety of interesting talk programs on the air, including one hosted by controversial former Boston Mayor James Michael Curley. Furman also refocused WBMS’s music to play more of the hits. And he hired Lewis to host his own radio show.

By now, Boston had more than 60,000 Black residents, and Furman believed they would respond well to a Black announcer. He was right. Lewis, who was identified in station advertising as a “popular colored bandleader,” was well-received, and not just by the Black audience; he also had a strong following among white listeners, many of whom had come to see him at the clubs over the years. On his program, Lewis played jazz and dance music and interviewed celebrity musicians who were in town; given his own long career, he knew a lot of them on a first-name basis, having performed in many of the same clubs as they had over the years.

Some sources have reported, erroneously, that Lewis was Boston’s first Black deejay. He was not. Back in 1949, WVOM (the Voice of Massachusetts) hired another jazz musician, Eddie Petty, and gave him a show for about a year. In addition, WVOM briefly hired another jazz artist, Jimmy Givens, as a deejay, around 1951. But while Lewis wasn’t Boston’s first Black deejay, he was certainly the one with the most longevity, staying at WBMS for five years while continuing to perform at local clubs. For most Bostonians of the era, whenever they thought about jazz, they thought about Lewis and his band.

Car accident, Later years

Lewis’ radio career ended around 1957 when WBMS was sold, became WILD and made staff changes, and he returned to doing what he did best on a full-time basis – entertaining live audiences. In 1963, his storied career was almost permanently ended after a drunk driver crashed into his car, causing serious damage to Lewis’ left hand and making playing the piano difficult. He left the music industry shortly thereafter and worked as a housing inspector at the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination before returning to the stage in the mid-1970s.

Death, Legacy

Sabby Lewis died in July 1994. He was 79. Right up until the day he finally retired, many local jazz musicians considered him both a mentor and an inspiration. He received a number of awards, including a 1984 proclamation from then-Governor Michael Dukakis in honor of his decades in the music industry; the Martin Luther King Music Achievement Award in 1988; and a posthumous induction into the New England Jazz Hall of Fame in 2001.

(by Donna Halper)

Former deejay, music director and radio consultant Donna Halper is a Boston-based historian who has spent over three decades as a professor, teaching media-related courses at Emerson College, the University of Massachusetts and Lesley University. She’s the author of six books including Boston Radio: 1920-2010 (Arcadia Publishing, 2011) and has written articles for a variety of publications. Dr. Halper was inducted into the Massachusetts Broadcasters Hall of Fame in 2023.