South End Shout: Boston’s Forgotten Music Scene in the Jazz Age

In Frederick Douglass Square, the center of Boston’s Black community in the 1920s and 1930s, many young jazz enthusiasts looked to the Harmony Shop as a source for networking. The site was razed in the 1960s for the Douglass Park Apartments.

The shop was located on Westfield Street, a former L-shaped strip that linked Tremont Street with Camden and Lenox Streets, and was owned by Harry “Bish” Hicks, a pianist and saxophonist and leader of Hicks Famous Jazz Band and Concert Orchestra. The combo played syncopated dance rags with Hicks on piano and sax, D. Clarence Atkins and David Laney both on banjo and trombone, Richard Ward on drums and traps, George Rickson on piano and banjo, and Henry Batchelder, pianist and “tenor jazz comedian.”

In April 1919, Hicks Famous Jazz Band played at Ruggles Hall for the 13th Anniversary of Eureka Lodge no. 8 of the Knights of Pythias. The next month, the band was featured in a homecoming celebration at Hibernian Hall on Dudley Street, Roxbury. The advertisement informed that “After a very successful tour of the State of Maine during the last four weeks the Hick’s [sic] first string orchestra will return to their own native Boston and show that they have lost none of their Jazz or Harmony.”

In addition to selling records, sheet music, and instruments, the Harmony Shop was a source of information on concerts and jobs. Hicks ran the booking agency Harry Hicks & Co., which recruited bands for college and society dances. The shop also provided rehearsal space and was the site of jam sessions – additional research is needed to determine whether they also recorded songs under a label.

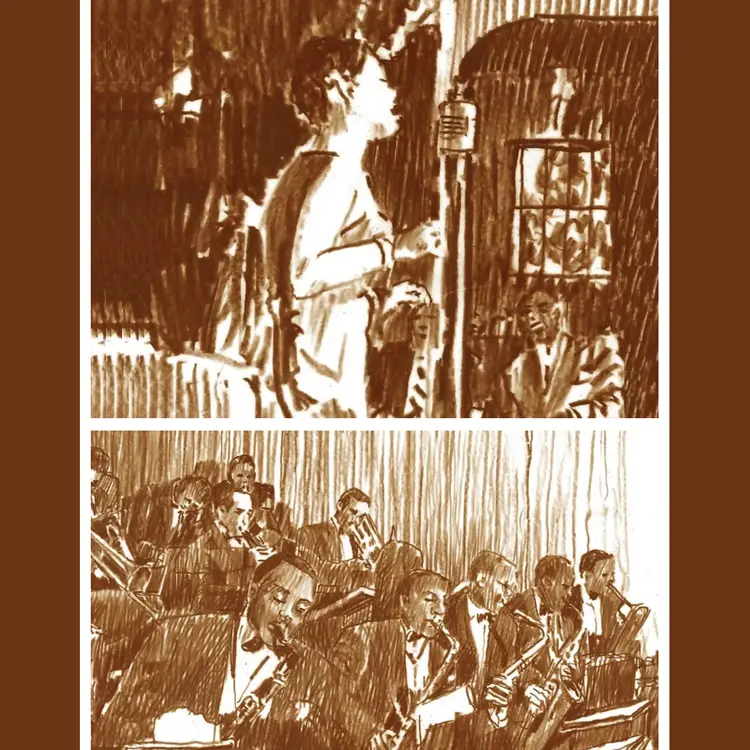

Drummer George Latimer remembers, “Every Sunday afternoon all the cats used to bring their instruments and we’d have a jam session, with the door wide open and the crowd in the street around the door getting a load of it.”

The shop was also a place for referrals to rent parties – known as “house hops” – similar to those enjoyed by migrant families in Harlem and South Side Chicago. Some old-time residents of the Square recall such activity in the neighborhood during the jazz age. Collin Corbin, born in Boston in 1921, describes the enjoyment of such events: “We use to go to a lot of house parties. Different friends would give a house party and we’d go to them.” Johnny Hodges spoke about earning money as a boy by playing piano at neighborhood “house hops” where admission was charged for people to join the dance.

As a result, the Harmony Shop became a gathering place for local musicians, touring jazz bands, and students at the New England Conservatory and Boston Conservatory. Youths could peruse the record bin and sheet music holdings, seek advice from professional players, and maybe even find a mentor in one of the older students from the conservatories.

Howard Johnson, for one, became friends with Jerome Don Pasquall, a jazz composer and arranger, and clarinetist and alto saxophonist. Raised in Fulton, Kentucky, Pasquall came to Boston as a seasoned musician to study at the NEC. He was admired for his vast knowledge of music and for his generosity in sharing it with younger enthusiasts.

Living in Boston between 1923 and 1927, Pasquall played with local bands as well as with the touring shows of Will Vodery, Noble Sissle, Fletcher Henderson, Jabbo Smith, Tiny Parham, and other Harlem entertainers, and Johnson convinced Pasquall to work with him and Johnny Hodges. In 1927, he was hired to play alto saxophone in the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra in New York City, and became a source of information for South End musicians interested in the jazz scene.

Benny Waters took periodic classes in theory, harmony, solfeggio, and more at the Boston Conservatory. The jazz musicians in Boston took pride in a reputation for their knowledge and ability to read music when many in the field relied on head arrangements. “It was an advantage for me to study, and it was rare, at that age, to study,” Waters recalls, adding, “If you know what the other fellow’s doing, then you can copy.” He took classes for five years and picked up work with the band of banjoist Bobby Johnson. Waters, in turn, mentored Harry Carney and Johnny Hodges, among other young people in the neighborhood.

The amenities of Frederick Douglass Square were an attraction to out-of-town entertainers as well. The arrival of traveling bands added to the legitimacy of the local talent and audience. The sight of brass bands marching down the streets and performing under the pavilion in nearby Madison Park in Lower Roxbury was applauded.

The park was a central location for the recreation of residents in the summertime. Located at Tremont and Ruggles Streets, the park sheltered residents who sought escape from their sweltering rooms and tenements. Charles Thomas recalled walking to the park with his mother, watching the crowds sauntering about, and sitting in bleachers to watch the Boston Tigers play. He also spoke about listening to brass bands playing popular tunes and ragtime dance music in the pavilion and on the streets.

(by Roger House)

For more information, see https://www.southendshout.com/

Roger House, Ph.D., is the author of South End Shout: Boston’s Forgotten Music Scene in the Jazz Age, published by Lever Press in June 2023, and an associate professor of American Studies at Emerson College in Boston.