Johnny Hodges

Cornelius “Johnny” Hodges was born in 1907 on Putnam Street in Cambridge, the youngest of four children. Today, he is generally regarded as the second most important alto saxophonist in jazz history, behind only Charlie Parker.

Hodges’ family moved to Boston’s South End where his father worked at the Back Bay railroad station (as a porter) and in hotels and restaurants (as a waiter). The neighborhood on Hammond Street where Hodges grew up came to be known as “Saxophonist’s Ghetto” after the many practitioners of the instrument who lived there, including Harry Carney who, like Hodges, went on to be a long-time member of the Duke Ellington Orchestra.

MUSICAL BEGINNINGS, EARLY APPEARANCES

The Hodges family was a musical one. Young Johnny was given piano lessons by his mother and “beat up all the pots and pans in the kitchen” playing drums on them, but he decided on the saxophone because a particular soprano model he saw in a store window “looked so pretty.” While he would maintain throughout his life that he received little musical training, he received both formal lessons from a student at New England Conservatory (among others) and informal instruction from fellow saxophonists whom he persuaded to show him what they knew.

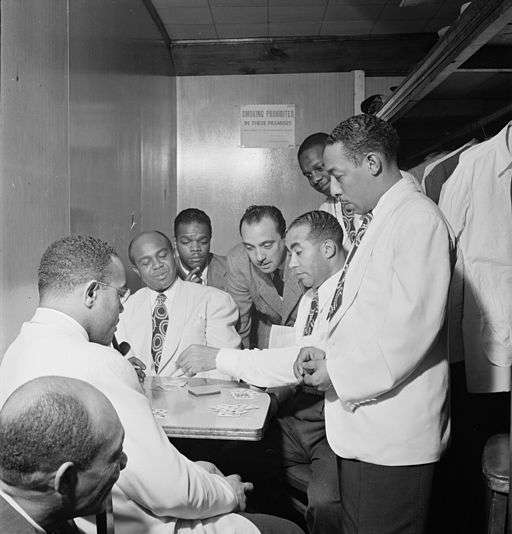

He played in the Boston area as a teen and had his own group in the Scollay Square entertainment district, fashioning his style in imitation of Sidney Bechet and Louis Armstrong. He began to travel to New York City in search of greater opportunities, partly because nightclubs closed at 11pm in Boston, but stayed open until 4am in “the city that never sleeps.” Venues where he played in the Boston area include the Avery Hotel, Lamp’s Club, the Black and White Club and the Alpini Restaurant in Kenmore Square. His first jobs in New York City were at “dancing schools,” venues where men could meet women but which provided no actual instruction. He became known to bandleaders through all-night jam sessions and eventually worked with Willie the Lion Smith, Bechet and legendary drummer Chick Webb.

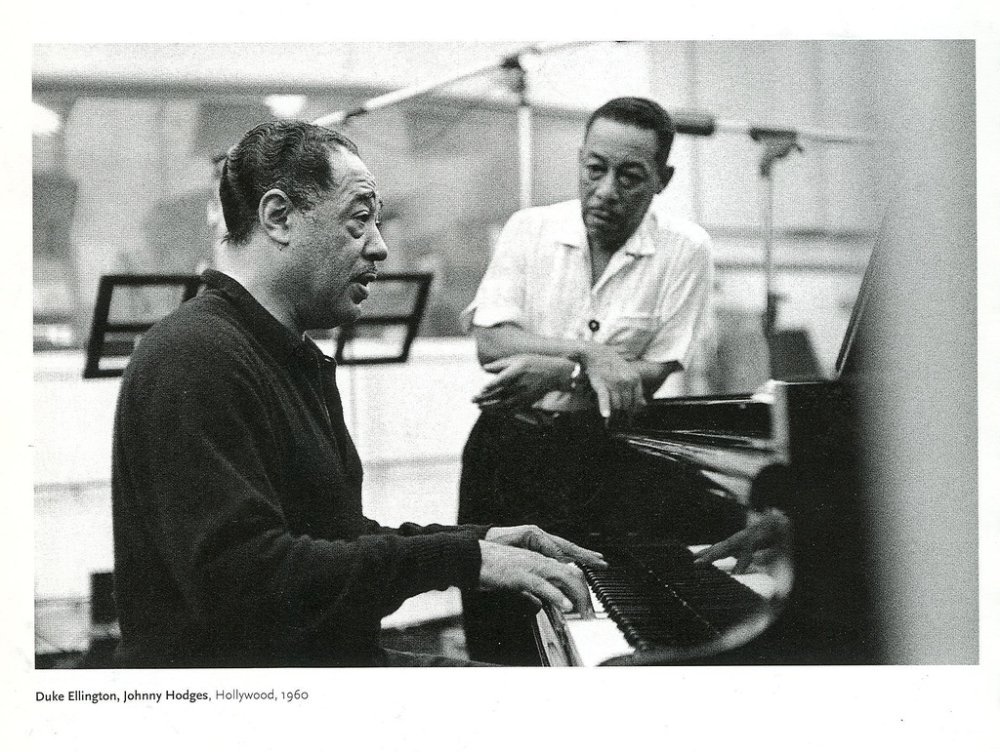

JOINING ELLINGTON’S BAND, COMPOSITIONS, NICKNAMES

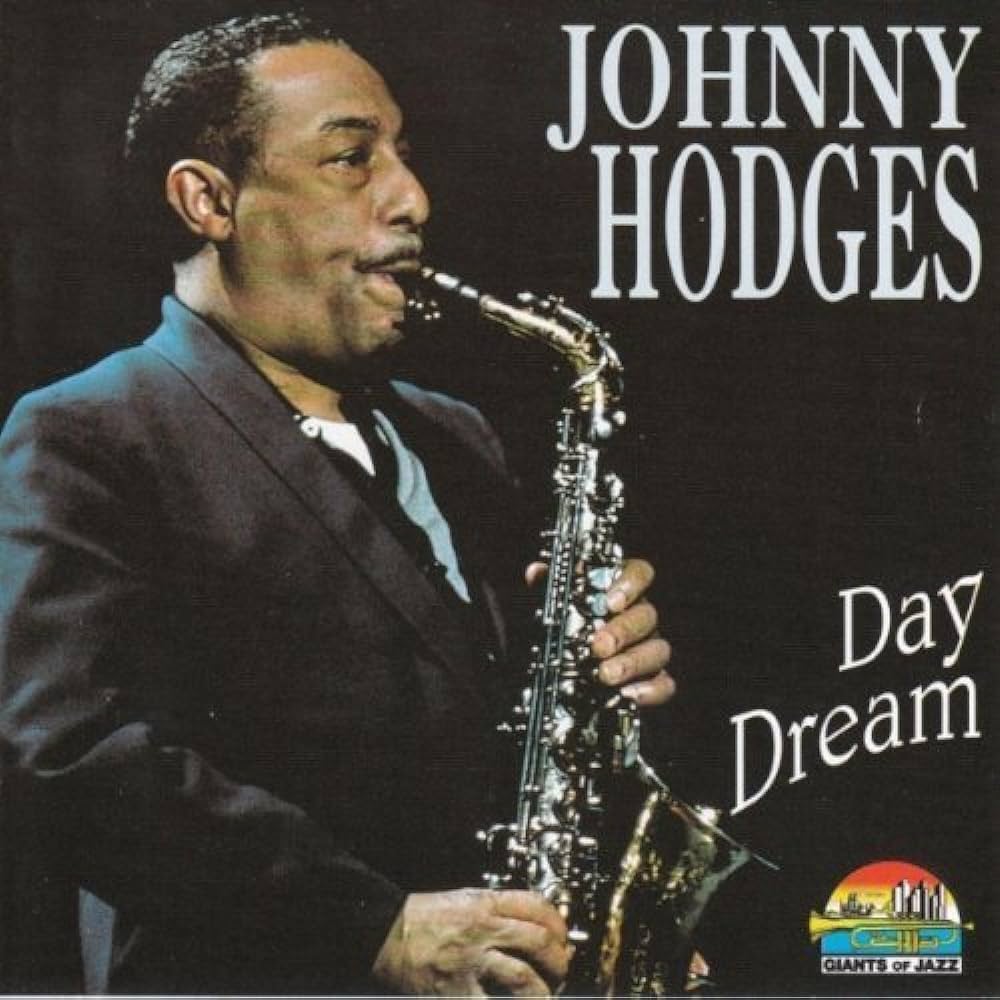

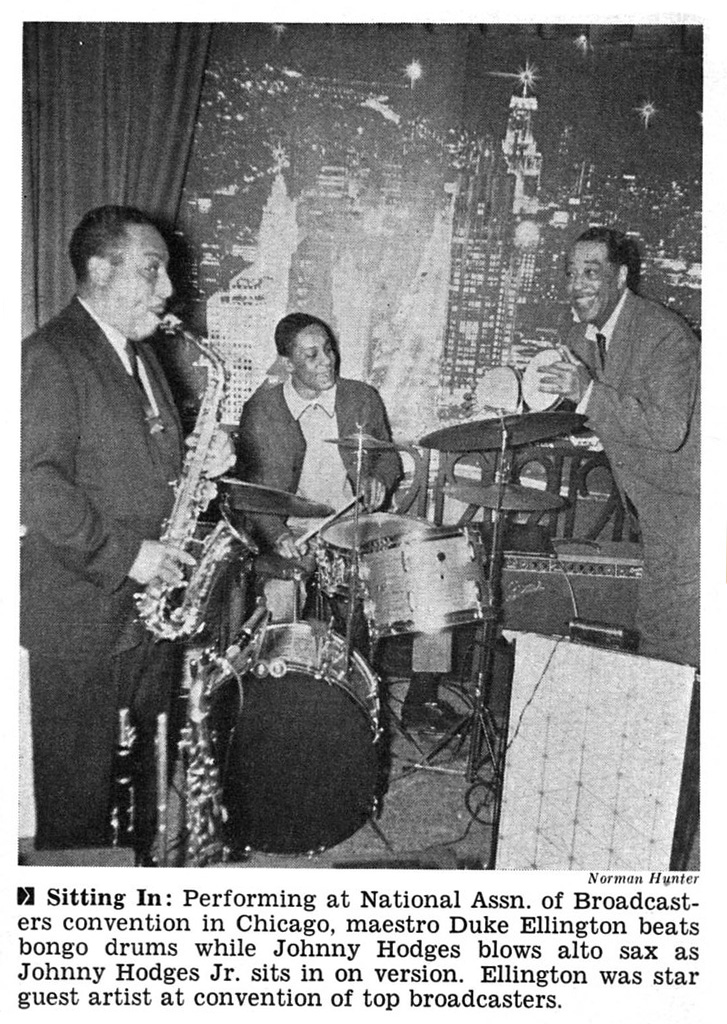

Webb’s band served as a farm team for other bandleaders, and after several unsuccessful attempts by Ellington to lure him away, Hodges finally left Webb for Ellington in 1928. Over time he became the leading soloist in the band, achieving headliner status due in large part to his lush tone, which Ellington often showcased on ballads. He remained steeped in the New Orleans blues he had absorbed listening to Bechet and Armstrong, however, and contributed compositions such as “Jeep’s Blues” and “The Jeep Is Jumping” that served as a counterweight to Ellington’s more ambitious orchestral works.

The use of “Jeep” in both tunes is no surprise sine that was of Hodges’ many nicknames (after a character in the Popeye comic strip). The most widely used of his monikers was “Rabbit,” which he said was due to his ability to outrun truant officers as a boy but which his neighborhood pal Carney attributed to his rabbit-like appearance when he was eating lettuce and tomato sandwiches.

LEAVING ELLINGTON, RETURNING TO ELLINGTON

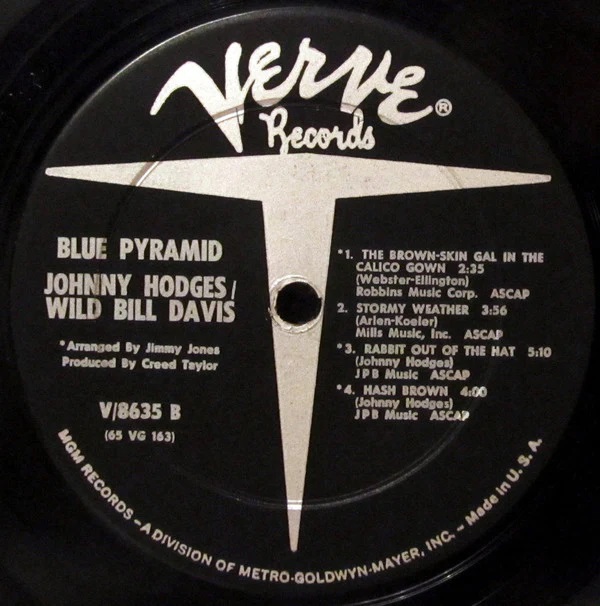

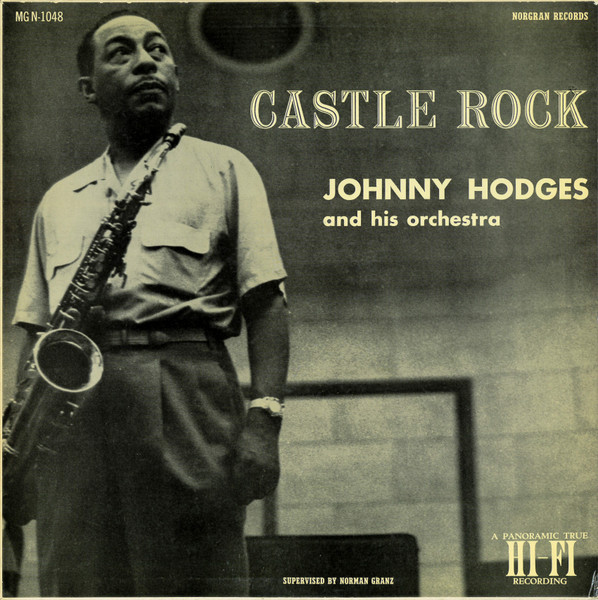

Hodges left Ellington in 1951 with support from record producer Norman Granz, who persuaded him that he could make more money as a leader than as Ellington’s employee. He took two other defectors from Ellington with him, drummer Sonny Greer and trombonist Lawrence Brown, and along with a rotating roster of sidemen they performed as Johnny Hodges & His Orchestra or in smaller configurations like The Johnny Hodges Septet.

The group had a hit that presaged rock ‘n’ roll, “Castle Rock” (on which Hodges did not solo), but he found that he didn’t have the personality to be a strong frontman and disliked the many administrative tasks he was saddled with that Ellington with his larger organization could delegate to others. He disbanded the group and was playing in the house band on a television show when his wife called Ellington and asked if he needed an alto. The Duke hired Hodges back in August of 1955.

COMEBACK, DEATH, BLUES SUMMIT

Charlie Parker had died in March of that year, and Hodges enjoyed a comeback beginning at the age of 48 that coincided with the Ellington band’s revival following its historic performance at the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival. He died in 1970 at the age of 62 in the middle of a procedure at his dentist’s office; feeling chest pain, he stood up and had a heart attack. At his funeral, Duke Ellington said that his orchestra would “never sound the same” without him.

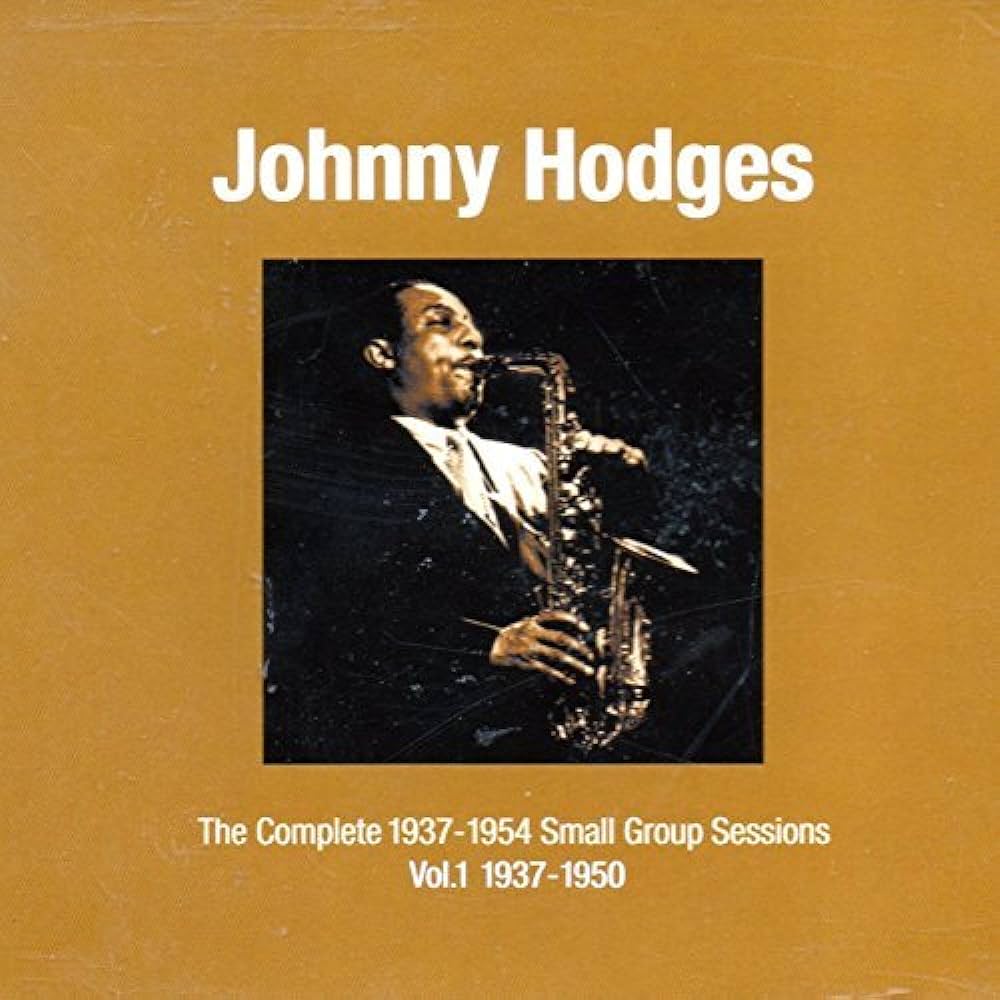

Much of Hodges’ music remains available on CDs and streaming services. A good introduction is Blues Summit, a two-album compilation of recordings he made with Duke Ellington and small groups originally titled Back to Back and Side by Side. In the six decades since these sessions were recorded, they have never gone out of print.

(by Con Chapman)

Con Chapman is the author of Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges (Oxford University Press, 2019), Kansas City Jazz: A Little Evil Will Do You Good (Equinox Publishing, 2023) and Sax Expat: Don Byas (University Press of Mississippi, 2025).