New Bedford Folk Festival

While the Newport Folk Festival became the genre’s preeminent showcase soon after George Wein founded it in 1959, it wasn’t the first of its kind in New England, nor is it the region’s longest running. The oldest is the New England Folk Festival, which started in 1944 – when the folk-revival freight train that barreled across the nation in the ‘50s and ‘60s was just leaving the station – and continues to this day.

And over the past eight decades – during which time the NEFF has been held in Massachusetts (Boston, Worcester, Brockton, Lowell, Natick, Marlborough), New Hampshire (Exeter, Manchester) and Rhode Island (North Kingston) – dozens of other multi-day folk and world-music celebrations have come and gone across the area. Among ongoing ones are the Lowell Folk Festival and the Green River Festival in Massachusetts, the CT Folk Fest in Connecticut, the Ossipee Valley Music Festival in Maine and the Mountain Bluegrass and Roots Festival in Vermont, all of which went ahead in 2023 after surviving two years of Covid-19 shutdowns.

Among the ones that didn’t weather the pandemic’s storm well enough to stay afloat was the New Bedford Folk Festival, held in July, which folded up its tent after 25 years following the 2022 event. Despite its extremely convenient locale – about 30 miles from Providence, 55 from Boston and 60 from Worcester – the organizers decided that rising costs made the festival unsustainable, echoing announcements of a 2023 hiatus or complete closure by the Vancouver Folk Fest, the Philadelphia Folk Fest and northern California’s Kate Wolf Music Festival.

“Covid was brutal,” said Rosemary Gill, president and CEO of Zeiterion Performing Arts Center, which produced the New Bedford event from 2016, in a February 2023 interview with The Boston Globe, noting that there were several other contributing factors such as not wanting to put the situation “on the backs of festival-goers” by raising ticket prices. “Expenses for the festival doubled, from renting port-o-johns to sound equipment,” she said.

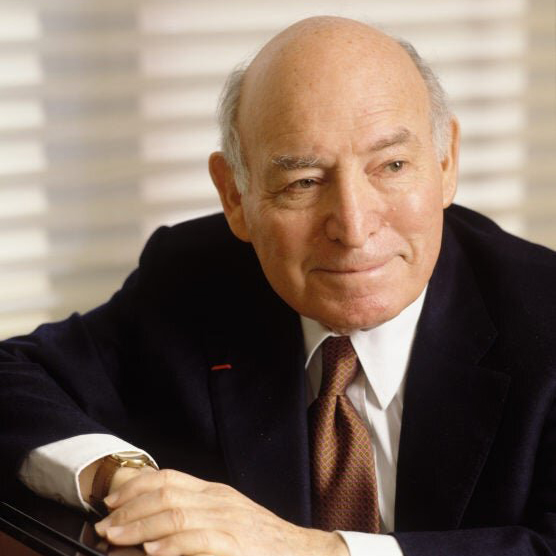

Alan and Helene Korolenko, Attendance, Revenue Generation

Called Summerfest from its opening year, 1996, until 2013 when it was renamed the New Bedford Folk Festival, the original coordinators were Alan and Helene Korolenko of Westport (about six miles outside New Bedford), who had been on the steering committee for the Eisteddfod Folk Festival at UMass Dartmouth in 1987 and 1988 and were the New Bedford event’s musical directors after Zeiterion took over its production.

In each of the festival’s last five years, about 3,000 people bought tickets and roughly 15,000 tourists flocked to the New Bedford area on the weekend of the event, contributing some $3 million to the local economy, according to Zeiterion’s Gill.

“One of the reasons Helene and I continued and enjoyed it right from the beginning is not just to put on the event, which is fine, but we’re doing something for the city,” Alan Korolenko said in an interview with The New Bedford Light in 2022. “We were able to do something positive and bring people into the city. All of a sudden there’s thousands of people milling around, including the performers. They want to go into a restaurant and check out the stores. I’m sure it had a positive effect.”

Debut Event, Steady Growth, Celtic Extravaganza

The debut event in 1996 featured three stages at State Pier on the city’s central waterfront, where there was also a carnival and a seafood tent, and two others for performers and crafts at what it now New Bedford Whaling National Park. By 2008, the event had grown to seven stages across 11 downtown blocks and presented 50 acts, 35 nationally known and 15 up-and-coming regional artists. The festival’s first outing introduced what became one of its most popular events, the Celtic Extravaganza, held as its finale, the debut performance being hosted by Scottish fiddler Johnny Cunningham before an audience of just 90. By 2013, attendance was over 1,000.

Improvisational Artist Workshops, Artist Tributes

In 1997, the Korolenkos added an element to the program that distinguished the New Bedford Folk Festival from other events: 75- to 90-minute workshops in which artists who’d never performed together gathered in groups of between three and five and created songs around a theme provided by the event organizers, turning part of the festival into an improvisational challenge that became a crowd favorite. “Having workshops that combined Celtic, bluegrass, blues, French Canadian and other genres, you have spontaneous situations going on throughout most of the two days,” Alan said in 2022. “It makes for a classic folk festival. When you have all these first-rate musicians in New Bedford on the same weekend, it would be unfortunate not to put them together.”

The first workshop, in 1997, was “Songs of the Sea.” Others included “Those Great Old Standards” featuring singer-songwriter (and New Bedford-area local legend) Art Tebbetts and folk-blues great Dave Van Ronk (1998); “Sound Your Instruments of Joy” with New York-based folk rockers The Kennedys and Canadian folk quintet Mad Pudding (2000); “Two Ends of the Same Spectrum” with electric-folk band Little Johnny England and English a capella quartet The Copper Family (2002); “The Greatest Squeezebox Ever” with accordionists Phil Cunningham of Scotland, John Whalen of Ireland, Gareth Turner of England and Benoit Bourque of Quebec (2003); “A Couple of Guitar Players” with English singer-guitarists Brooks Williams and John Renbourn, New England Conservatory graduate Raymond Gonzalez and Minneapolis-born Peter Lang (2005); “Kind of Blue: Jazz, Blues and Folk” with singer-songwriters Susan Werner and Chris Smither, vocalist Vance Gilbert, violinist Jeremy Kittel and drummer Nathaniel Smith (2010); and “How Can I Keep From Singing the Songs I Love” with Werner, Grammy-winning singer-songwriter Aoife O’Donovan and singer-songwriters Patty Larkin and Catie Curtis (2017). The festival also hosted dance workshops, the first being “Dancing Feet” in 1998, led by percussive-dance pioneer Sandy Silva.

In 2006, the Korolenkos introduced another novel feature, tributes to specific artists, the first being “God Help the Troubadour: The Songs of Phil Ochs” with singer-guitarist-pianist John Gorka, folk duo Kim and Reggie Harris and singer-songwriter Bob Franke, hosted by Ochs’ sister Sonny. Others included Tebbetts’ 2006 homage to singer, writer and historian Paul Clayton, a New Bedford native who was a notable figure on the Greenwich Village scene in the ‘50s/‘60s, a 2010 tribute to Richard and Mimi Fariña featuring The Kennedys and singer-songwriter Caroline Doctorow and a celebration of The Everly Brothers’ musical catalogue in 2014.

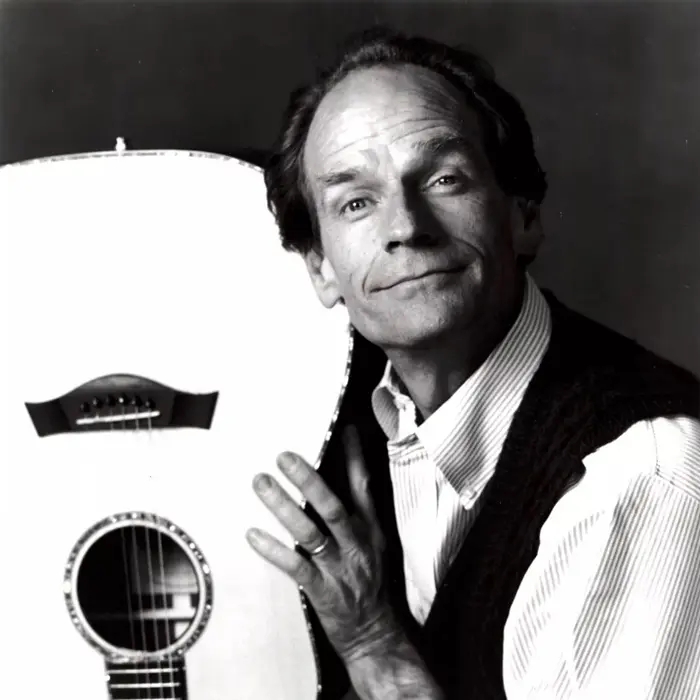

Korolenkos Retire, Zeiterion Takes Over, Rumors of Closing

In 2015, when Tom Rush, John Hammond and other headliners appeared for the festival’s 20th anniversary, the Korolenkos retired and Zeiterion Performing Arts Center, a 1,200-seat venue in downtown New Bedford, assumed all production duties. Rumors that the 2015 event would be the festival’s last were not entirely unfounded, according to Zeiterion CEO Gill, since the event’s future was uncertain from there forward. “Every year, at the end of the festival, Alan and Helene and I would kind of look at each other like, ‘Should we do it another year?’” she told The Boston Globe in February 2023. “ We considered it on a year-to-year basis in the last few years – we wanted to get to the 25th.”

Deciding to Close, Final Festival, “Not-to-miss Artists”

The festival saw steady attendance increases over the years, Gill said, particularly in 2016 when Kate and Livingston Taylor performed, but by 2022 the event was “taking a toll on regular [Zeiterion] staff,” the payroll for which hadn’t been factored into the festival’s expense budget of several hundred thousand dollars. “We would have had to put a lot more money into it to really do it well. And we just couldn’t see that happening,” she said. “Although we had some short-term solutions – including the city offering to help – we didn’t have anything long term. So we thought [closing after 25 years] was the most elegant way of going out.”

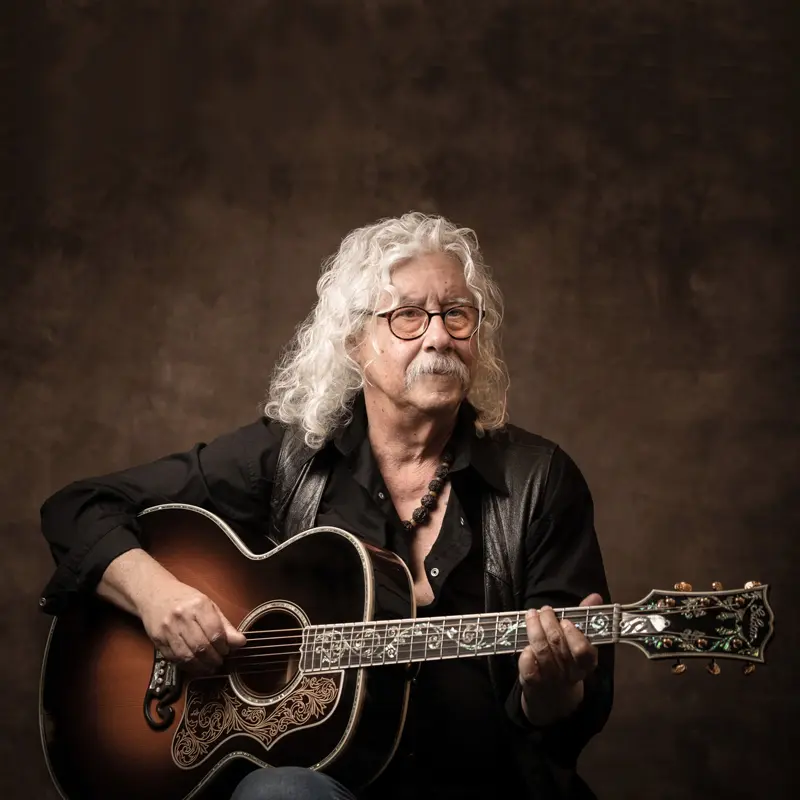

Among those appearing at the 25th event were musicians The Boston Globe called “five not-to-miss-artists” in a July 2022 feature: Tom Rush; Boston-based singer-songwriter Alisa Amador, winner of NPR’s Tiny Desk Contest in 2022; bluegrass sensation Beppe Gambetta of Genova, Italy; singer-songwriter Cheryl Wheeler, a Rhode Island Music Hall of Fame inductee; and jazz/folk singer-songwriter Vance Gilbert, who’s shared the stage with Shawn Colvin, Aretha Franklin and Arlo Guthrie.

Likelihood of Returning, Tom Rush Comments

Asked in 2023 if the festival might return under new management in the future, Gill said she hoped so but that she was not aware of any immediate interest from other production/promotion organizations. Alan Korolenko said he and Helene welcome any opportunity to continue what he called “a miracle festival” and New Bedford Mayor Jon Mitchell said the city “would welcome the opportunity to discuss how we might support” any future proposals.

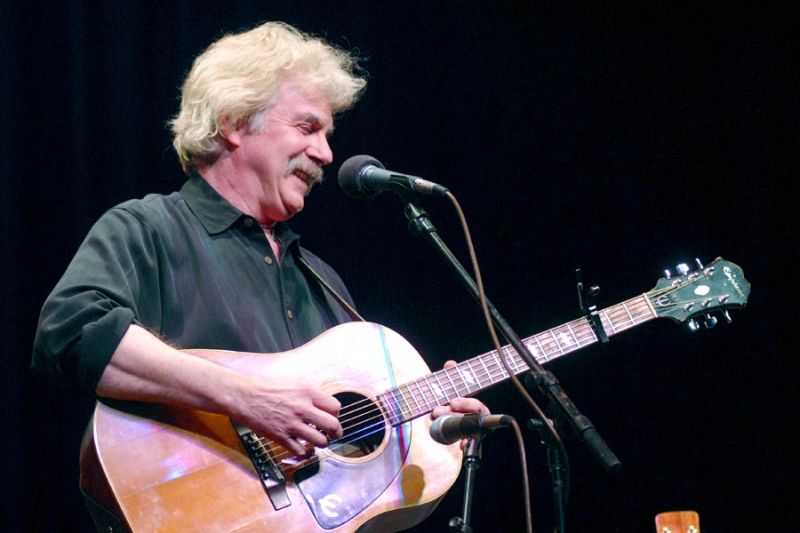

In a February 2023 interview with The Boston Globe, Tom Rush said he was “stunned” when he heard news of the festival’s closing. “It’s been such a central part of the music scene in New England for 25 years,” explained the 82-year-old folk icon, who appeared at the debut event in 1996. “To have it just suddenly evaporate was a bit of a shock.”

“I think there are layers of problems,” he continued, noting that the 2022 Folk Fest in Philadelphia was “seriously under-attended” and that Covid has had a negative impact on traditional folk festivals in general. “The older generation who have been the backbone of fests like this are still shy about going out in public, especially in crowds,” he said.

(by D.S. Monahan)