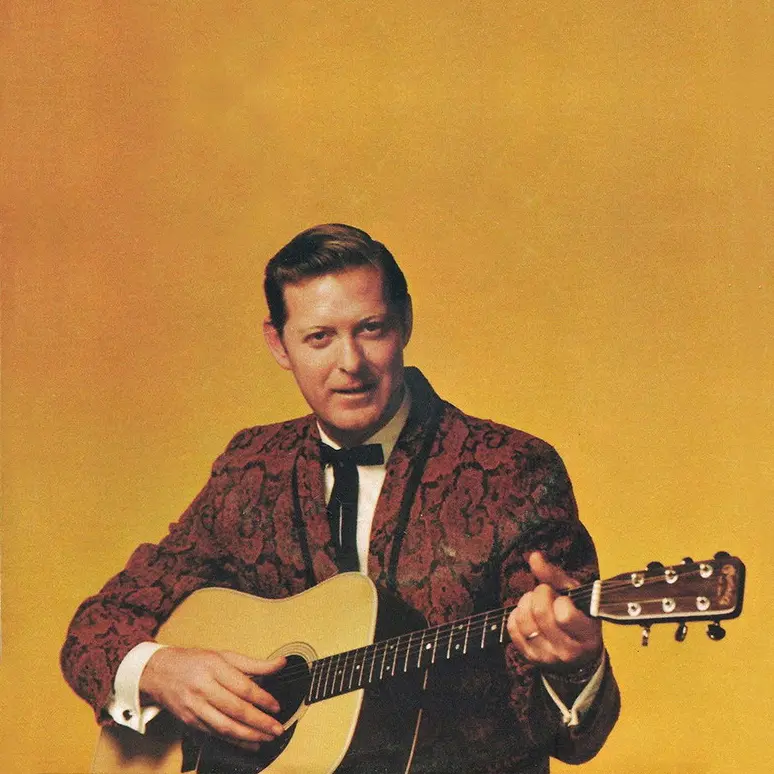

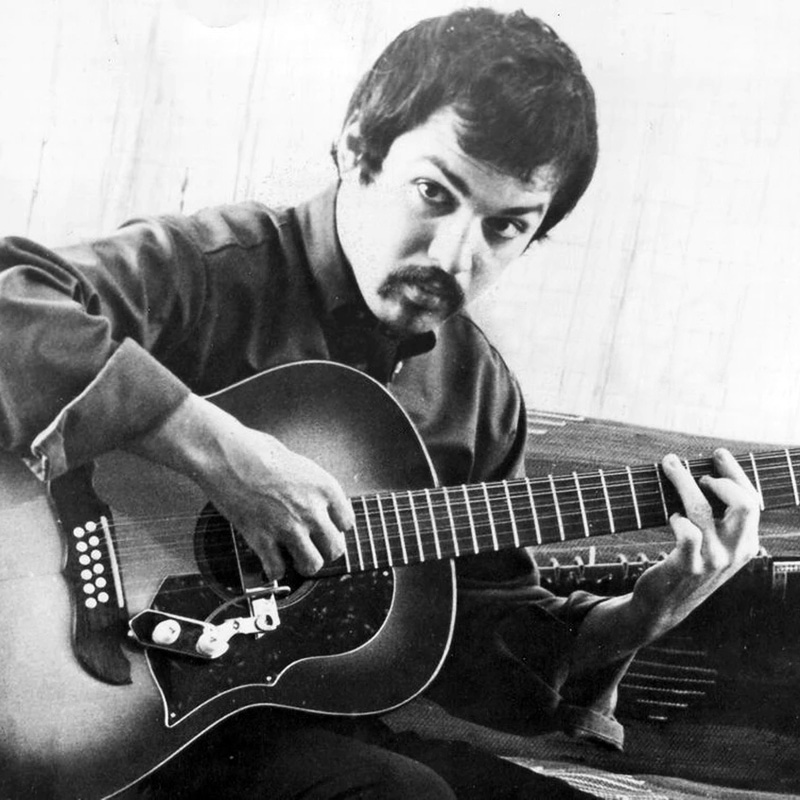

Lenny Breau

The vast majority of non-guitarists have no idea who Lenny Breau was, nor do most non-jazz guitarists on the scene today. Still, Chet Atkins once referred to him as “the greatest guitarist who ever walked the face of the earth,” according to the Maine Historical Society, and said “if Chopin had played guitar, he would have sounded like Lenny Breau.” Grammy-winning guitarist John Knowles, one of Breau’s former bandmates, has called him a “genius” and said that knowing him “was like knowing Vincent Van Gogh,” which echoed comments by Breau’s brother Denny, who said that Breau often described playing guitar as “painting with music.”

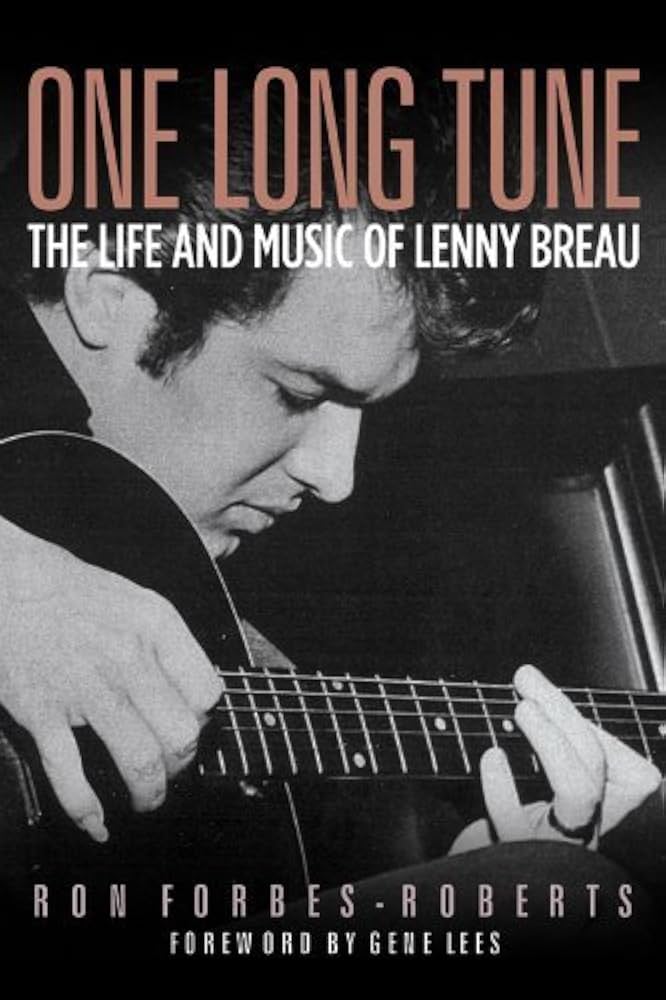

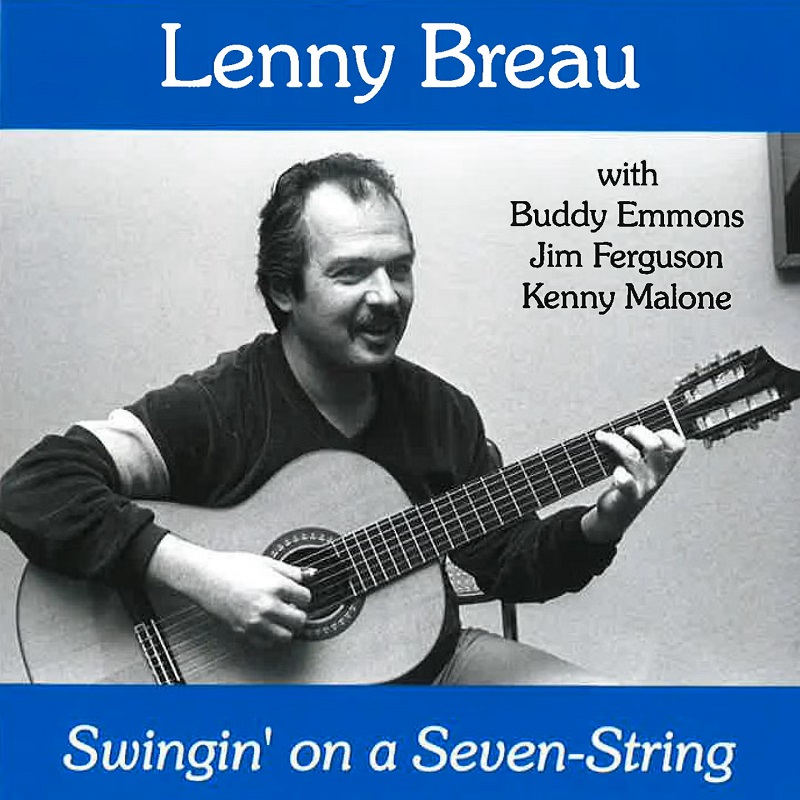

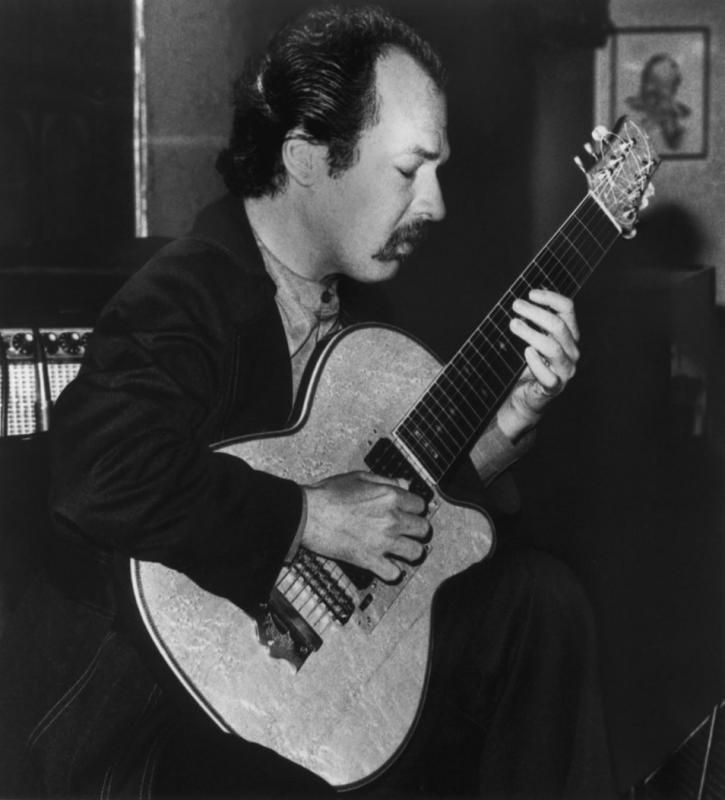

Despite such effusive praise and a global fan base that includes a who’s who of legendary jazz guitarists, Breau spent most his life in relative obscurity. A seven-string-guitar pioneer who combined country, flamenco, jazz and other genres into a cocktail all his own, he cut 10 albums during his lifetime, some of which are considered classics, and 21 collections of previously unreleased material have been issued posthumously, all of which are considered defining examples of his artistry. “He created techniques that baffled and amazed even the most accomplished guitarists of his time [and] the musical result enthralled listeners as much for its technical complexity as the depth of its emotional expression,” according to Ron Forbes-Roberts, author of the 2006 biography One Long Tune: The Life and Music of Lenny Breau. Breau’s LPs are “among the most important and groundbreaking guitar recordings ever made,“ he says, referring to them as “masterworks of fingerstyle jazz guitar.”

MUSICAL BEGINNINGS

Leonard Harold Breau was born in Auburn, Maine on August 5, 1941 to Pea Cove native Harold Breau and Rita Coté, who was born in Quebec but moved to Auburn with her family when she was less than a year old. The pair began performing as a country/western duo in 1938 using the stage names Hal Lone Pine and Betty Cody and had achieved significant regional success by the time Breau was born. Backed by The Lone Mountain Pioneers, they dominated the country charts in Maine and Canada’s Maritime provinces in the ‘40s and ‘50s, hosted WCOU in Lewiston’s Noisiest Gang on the Radio Show and appeared regularly on radio stations in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, on Prince Edward Island and on the national network, CBC. Both of Breau’s parents have been inducted into the Maine Country Music Hall of Fame.

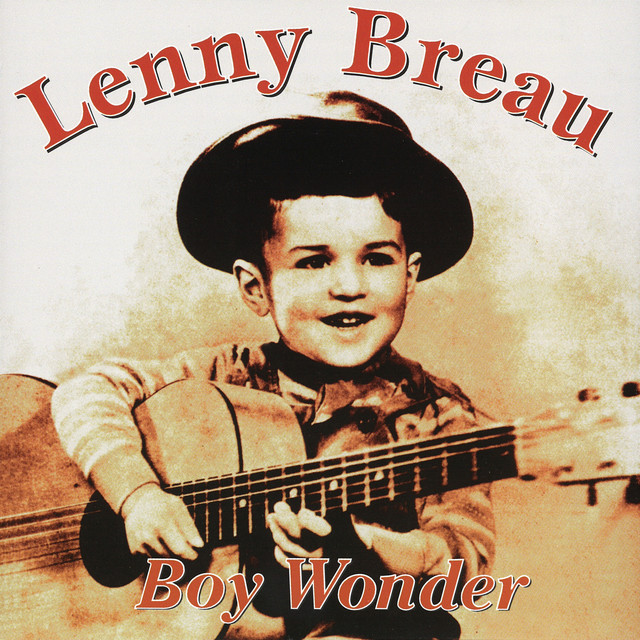

The Breau family lived on a farm, where they kept two horses and a pony for young Lenny, who demonstrated a keen ear for music years before he entered kindergarten. According to his mother, three-year-old Breau intuitively started singing the third-part harmony to Eddy Arnold’s 1944 hit “The Cattle Call” when he heard her singing it one day. Shortly after that, he began appearing with his parents on their radio show and at shows around New England, billed as “Lone Pine Junior” and referred to in the press as the “boy wonder” of the act, a role he played until age 18. Breau’s foray into guitar began around age five, when Lone Pine Mountaineers’ guitarist Ray Couture showed him the basic chords.

In 1948, the Breau family relocated to Moncton, New Brunswick, where they lived for the next several years. Breau developed his guitar skills significantly during that time, learning new chords and songs from the son of the family with whom he stayed while his parents were on the road, and by age nine he was playing jigs and reels with various groups at local barn dances. He had what he called a “life-changing experience” in 1952 when he happened to hear a Chet Atkins instrumental on the radio; his fingerstyle playing was like nothing he’d ever heard, Breau said, and he made every effort to learn the technique. He made tremendous progress doing so in 1953, the year he formed his first band, when he and his parents lived in West Virginia and were regulars on the nationally aired WWVA radio show Wheeling Jamboree.

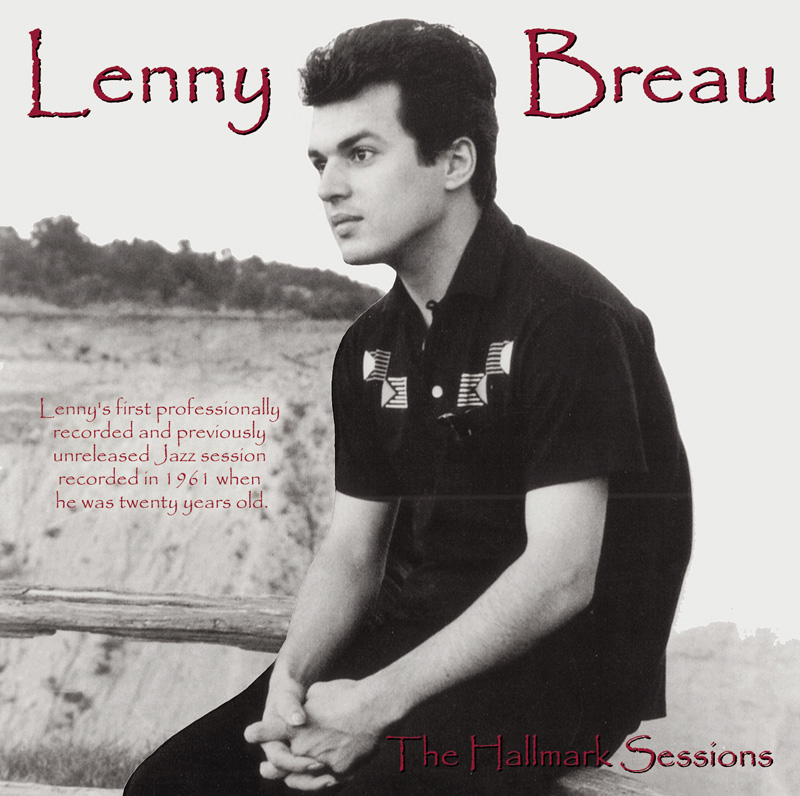

EARLY CAREER, 1960S COLLABORATIONS/RECORDINGS

The family returned to Maine in 1955, by which time 14-year-old Breau had all but mastered his Atkins-inspired style. When not performing with his parents’ band, he worked as a studio musician for Event Records in Westbrook, backing local artists including future country star Dick Curless. The studio owner, Al Hawkes, often recorded Breau playing solo and with other musicians between sessions, and in 1998 the Guitarchives label released 27 tracks from those informal jams (recorded in 1956) as Boy Wonder. In 1957, the Breaus moved to Winnipeg, Manitoba, where they performed on CKY-AM and venues around the city, with 16-year-old Lenny on lead guitar. While he was still the “boy wonder” of a country band, he’d taken a keen interest in bebop, which caused friction between him and his father.

Things came to head in 1959, when the younger Breau injected jazz riffs into a country tune during a performance on CHAB-AM in Saskatchewan, which led to this father slapping him across the face, according to biographer Forbes-Roberts. Breau quit his parents’ band and spent the next two years immersed in Winnipeg’s thriving jazz scene, working with the top players in the area. Most importantly, he met 29-year-old pianist-composer Bob Erlendson, who taught him jazz theory and often appeared with Breau at Rando Manor and The Stage Door in Winnipeg.

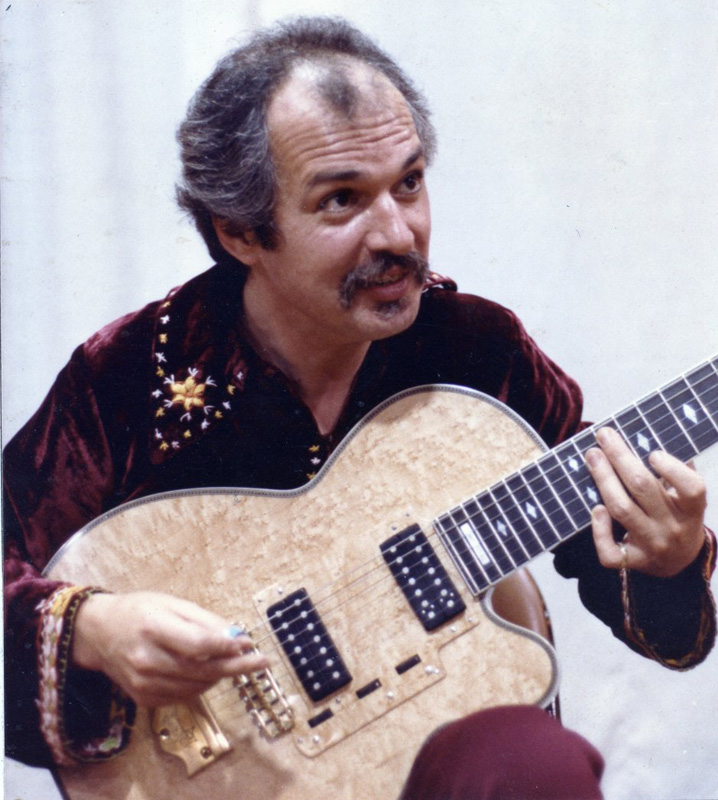

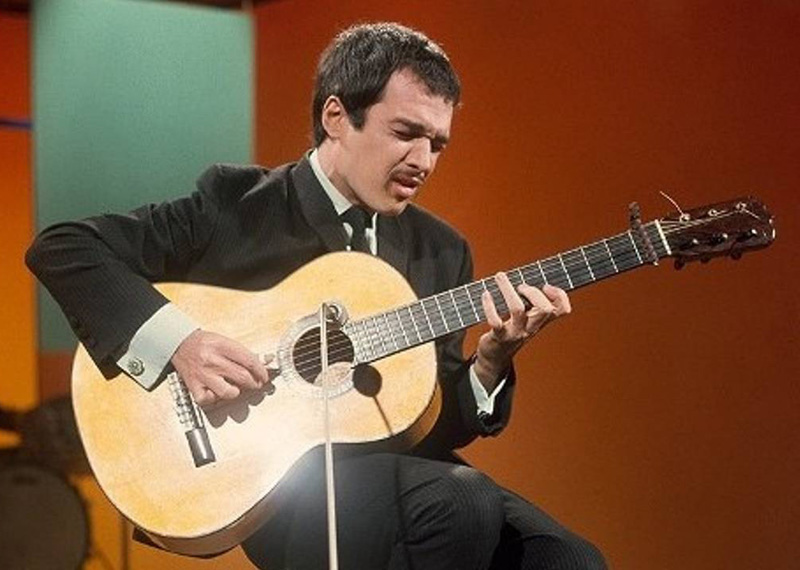

While Chet Atkins had been Breau’s biggest inspiration in the ‘50s, Erlendson’s influence led him to concentrate more on pianist Bill Evans’s material starting in 1960; over the next 20-odd years, he transposed much of the jazz legend’s complex harmonic and melodic concepts to guitar. He started incorporating elements of flamenco into his playing around the same time and, in an effort to blend guitar and piano melodies, commissioned two custom-built seven-string guitars, one classical and one electric. Breau relocated to Toronto in 1961, becoming a prominent figure on the local scene and co-forming the trio Three, which gigged in Toronto, Ottawa and New York City, appeared on The Jackie Gleason Show and The Joey Bishop Show and recorded a live album at the Village Vanguard.

CBC RADIO/TELEVISION, FIRST ALBUMS, HEROIN HABIT, RETURN TO MAINE

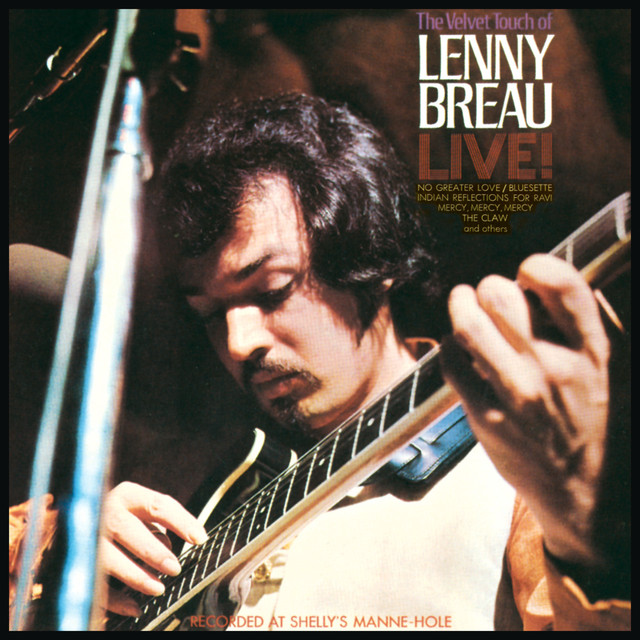

In 1962, Breau returned to Winnipeg, where he worked as studio musician for CBC Radio and CBC Television, and in 1966 he hosted a 30-minute variety show (The Lenny Breau Show), which paved the way for his first solo albums; he sent a tape of the program to Atkins, who’d recently become vice president of RCA’s country division, and Atkins offered him a recording contract. The ensuing LPs were Guitar Sounds from Lenny Breau (1968) and The Velvet Touch of Lenny Breau – Live! (1969), which are viewed as classics today but sold poorly, resulting in RCA dropping Breau from its roster.

By the time 1970 arrived, Breau was without a label, financially strapped and, making a bad situation worse, in the throes of a heroin habit he’d developed in the early ‘60s. His addiction made him so unreliable that clubs refused to book him, and touring artists became unwilling to hire him as a sidemen after 1972, when he started a tour with Anne Murray but was fired after a few shows due to his drug use. He moved from one Canadian city to another until 1976, when he kicked heroin while living on a commune in Ontario. A few months later, however, he was arrested for possession of marijuana with intent to traffic (a charge later dropped) and returned to Maine, where he spent the next year playing a variety of small venues including Lenny’s at Hawke’s Plaza in Westbrook, where he appeared regularly.

MOVE TO NASHVILLE, LATER RECORDINGS, FINAL YEARS, DEATH

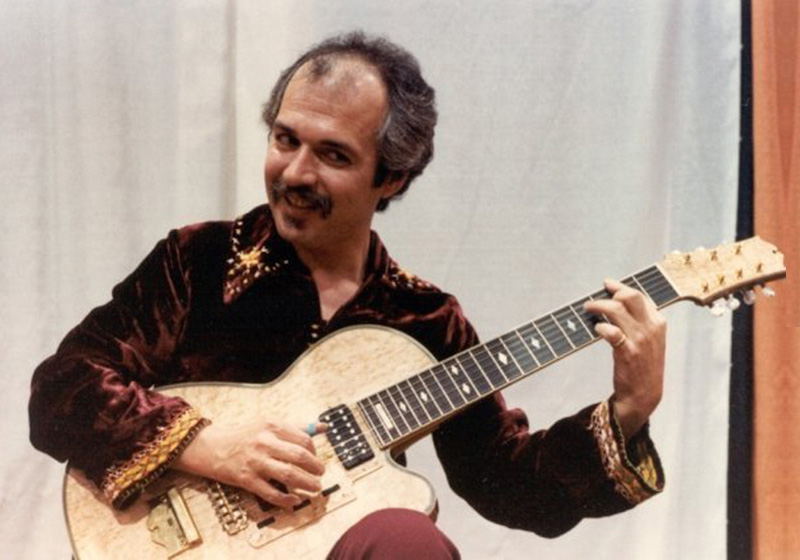

In 1977, Breau’s friendship with Atkins allowed him to jumpstart his career – he moved to Nashville to play a nightly gig Atkins had arranged – and the next five years were his most productive in terms of recording. He cut two LPs in Atkins’s home studio, The Legendary Lenny Breau: Live (1979, Sound Hole) and Standard Brands (1981, RCA Victor, a duet disc with Atkins); three for Adelphi, Five O’Clock Bells (1979), Mo’ Breau (1981) and Last Sessions (1988); and three others, Minors Aloud (1978, Flying Fish, with Buddy Emmons), When Lightn’ Strikes (1982, Tudor) and Live at Bourbon Street (1995, Guitarchives).

By early 1980, 39-year-old Breau’s career seemed to be back on track. Things fell off the rails later that year, however, when he took the stage drunk in Winnipeg and Vancouver and the press lambasted him for what were called “disastrous” performances. With his reputation north of the border in tatters, he returned to Maine and never performed in Canada again. He spent the next two years living in Maine, Nashville and Northern California (making a modest living by playing, teaching and writing for Guitar Player magazine) before settling in Los Angeles in 1983.

From then until his death the following year, he had a regular gig at Dante’s in North Hollywood and taught at The Guitar Institute of Technology. Breau’s GIT workshops became so popular that the school planned to offer him a full-time position starting in September 1984, but he never received the offer because he was found dead on August 12 that year, one week after his 43rd birthday. It appeared that he’d drowned since his body was found floating in the rooftop pool of his apartment building, but the coroner ruled the cause of death to be strangulation. Police named his wife as the prime murder suspect, but there was never enough evidence to charge her and the case remains unsolved.

POSTHUMOUS RELEASES, CANADIAN MUSIC HALL OF FAME, LEGACY

In the years immediately following his death, Breau’s role in the development of jazz guitar was largely overlooked and most of his albums were out of print or extremely difficult to find. Things started changing in 1995, however when Winnipeg native Randy Bachman founded Guitarchives, which has remastered and released a number of his unreleased and discontinued recordings. Breau, who held US and Canadian citizenship, was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame in 1997, and his daughter Emily Hughes has produced two well-received documentaries about her father, The Genius of Lenny Breau (1999) and The Genius of Lenny Breau Remembered (2018). In 2000, jazz guitarist Stephen Anderson published Visions, an instruction book on Breau’s style, and the Art of Life label began issuing previously unreleased and out-of-print recordings.

“It may be tempting to view Breau’s career as a series of missed opportunities and lament his lack of commercial success. But as his friend and bandmate Ron Halldorson put it, ‘Lenny was successful in the ways that mattered to him and in the ways that matter to real musicians,’” wrote Forbes-Roberts in 2018. “Breau’s lifelong passion was the creation of a beautiful, innovative guitar sound uniquely his own that would move and inspire his listeners. Considering the sublime music that he gave us, he clearly realized his goal.”

(by D.S. Monahan)

- Wikipedia

- Lenny Breau: The Van Gogh of Guitar Players - Maine Historical Society

- Official Home Page

- Discover the Flawed Genius of Guitar Master Lenny Breau - Guitar Player

- Have you heard Lenny? - The Boston Phoenix

- How Did Lenny Breau Do That? - Premier Guitar

- Lenny Breau Inducted in 1997 - Canadian Music Hall of Fame