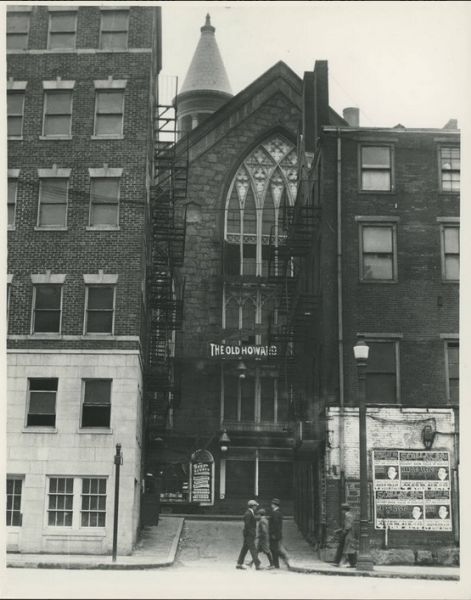

Howard Athenaeum / “The Old Howard”

The building has been gone for 61 years and the city square where it stood has been gone for 55. But for over a century, Howard Athenaeum – later called Old Howard Athenaeum and colloquially known as “the Old Howard” – was as historic a part of Boston’s urban landscape in terms of entertainment as Paul Revere’s house, the Old North Church and the Bunker Hill Monument are to the American Revolution.

And, in an historical irony far too rich to go unmentioned, the building’s origin had nothing whatsoever to do with entertainment. Though it would be condemned for housing what they considered a modern-day Sodom and Gomorrah by preachers of the both the 19th and 20th centuries, Howard Athenaeum was constructed on deeply “faith-based,” if ultimately shaky, grounds.

Background

The tent-shaped structure that became Howard Athenaeum was built in 1841, funded by William Miller, the Pittsfield, Massachusetts-born founder of the Millerite sect, which promoted the belief that Jesus Christ would return to Earth in April 1844, initiating the Apocalypse and the end of the world. In what Millerites called the Great Disappointment, that bold prediction went unrealized and by October 1844 – despite Miller making multiple revisions to his Bible-based calculations – the sect splintered apart, the flock having lost faith in its leader’s ability to predict humanity’s demise.

In early 1845, several of Miller’s parishioners – who had surrendered all of their worldly possessions in preparation for Christ’s allegedly imminent return – sold the property to a group of prominent Bostonians, who converted the church into a theatre, Howard Athenaeum. They named it after its Howard Street location in the area the city officially named Scollay Square in 1838 (after local developer William Scollay, who bought a landmark four-story building near the intersection of Cambridge and Court Streets in the district in 1795).

Opening, First performances, Fire, Reopening

Howard Athenaeum opened on October 12, 1845, with a positive review appearing the next day in The Boston Courier that referred to the building’s unique past. “The old tabernacle has been transformed into a very convenient and handsome theatre and it would sadly puzzle a Millerite to imagine himself at home in its now tasteful interior,” it read. The first performances were mostly Shakespeare plays and light comedies. In November 1845, the theatre presented New England’s first genuine Italian operatic performance, Verdi’s “Ernani.”

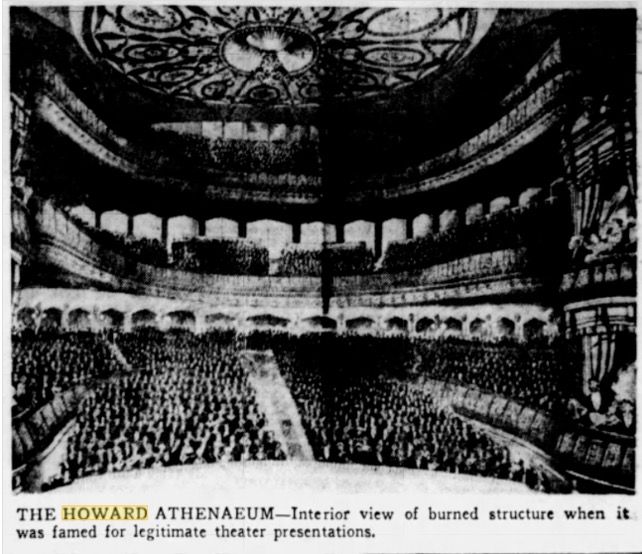

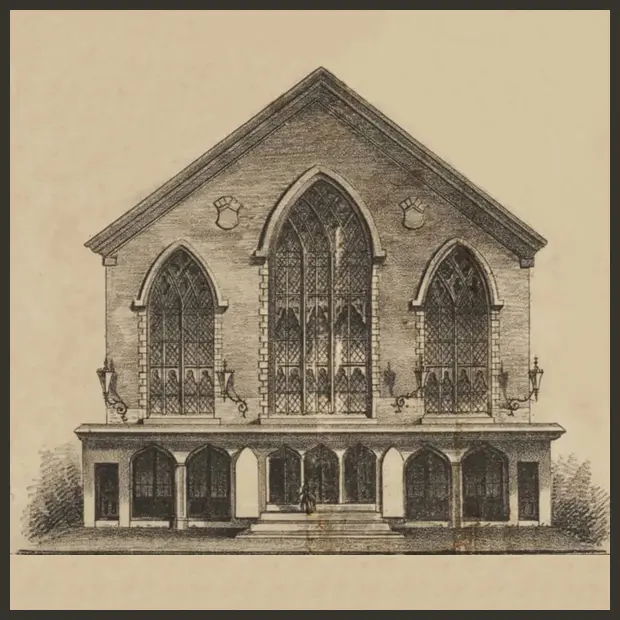

On February 23, 1846, less than five months after opening, the theatre burned to the ground. On October 5, 1846, constructed using Quincy granite through funding from a local brewery, Howard Athenaeum reopened – almost exactly one year after its first grand opening – with a performance of Richard Sheridan’s satirical comedy “The Rivals.” A Gothic-style structure that was extremely unique for the period, it was designed by Marshfield, Massachusetts, native Isaiah Rogers, had a seating capacity of 1,600 – reduced to about 1,400 in 1944 due to fire regulations imposed following the 1942 Cocoanut Grove fire – and featured a 36×43-foot stage large enough to accommodate extravagant productions.

Innovations, “Bald-headed section,” Entertainment program

Howard Athenaeum was the first Boston theatre with cushioned seats, and its newly added balcony and orchestra sections allowed for different levels of ticket pricing, a marketing breakthrough at the time. Within a week of its opening, scalpers were selling tickets for over double face value for sold-out shows. For reasons that have been lost through the decades, it became a tradition for the front row to be reserved for bald men, and those seats were known unofficially as “the bald-headed section.”

For the next 20-odd years, Howard Athenaeum presented a fabulously broad range of entertainment, from comedians, magicians and minstrel shows to serious drama, ballet and opera, such as in May 1847 when the first major opera company in Manhattan, Max Maretzek Italian Opera Company, performed Vincenzo Bellini’s “Norma: A Grand Lyrical Tragedy.” One of Boston’s two leading playhouses, the second being the Boston Museum (1841-1903), the theatre hosted some of the era’s most famous touring actors, including France’s Sarah Bernhardt and England’s William MacReady, but a Maryland-born thespian who appeared became infinitely more famous than them all: John Wilkes Booth, who assassinated Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865.

Anti-discrimination lawsuit

In 1853, eight years before the American Civil War began, Howard Athenaeum – which was the only theater in Boston to enforce racial segregation of its guests – found itself in the glare of the national spotlight when it became the epicenter of what historians have cited as the first anti-discrimination lawsuit.

Upon arriving to see an opera, 27-year-old anti-slavery activist and university lecturer Sarah Parker Remond, born and raised in Salem, Massachusetts, refused to be seated in the segregated section and was forcibly removed, being pushed down a flight of stairs in the process. She sued the venue’s management and won, the court awarding her $500 (about $18,850 in 2023) and ordering the theater to integrate all seating (101 years before US President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act outlawing racial discrimination in all public accommodations).

Vaudeville, Burlesque, “The Old Howard”

In 1868, with audiences decreasing due to the increase in the number of smaller theatres in Boston, Howard Athenaeum’s owners made a dramatic shift in the venue’s offerings, turning to the most popular variety of entertainment at the time: vaudeville, meaning variety shows that intermingled comedic dialogue and satirical songs.

In 1869, the theatre presented its first performance in a genre that would become its mainstay 30 years later, burlesque, meaning variety shows that intermingled striptease, risqué humor and sexually suggestive songs, essentially making them “adult vaudeville.” The debut burlesque show was by Lydia Thomson and Her British Blondes, Thomson being the first performer to introduce Victorian burlesque to American audiences and a superstar of the genre through the early 20th century. With the addition of vaudeville and burlesque, people began calling Howard Athenaeum “the Old Howard.”

Name change, Films, Embracing burlesque

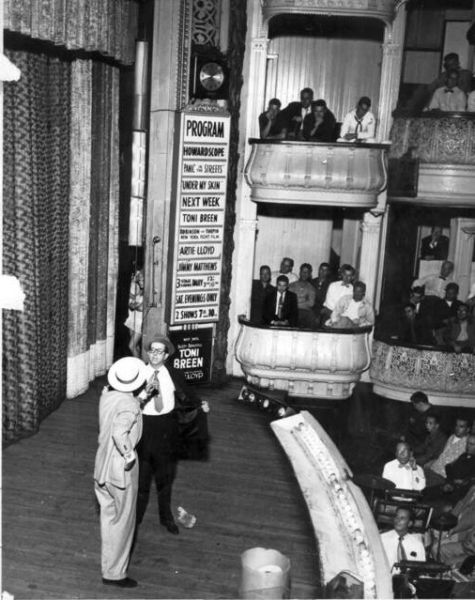

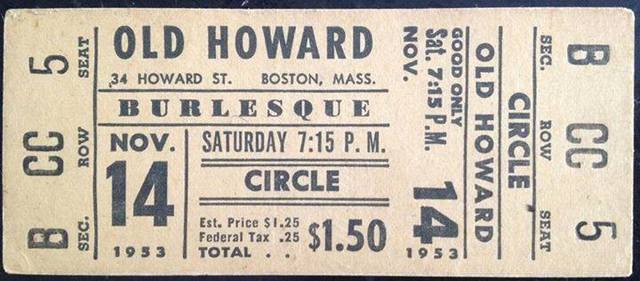

In 1897, the venue was renamed Old Howard Athenaeum and began presenting films, mostly of boxing matches, to attract customers when there were no acts on stage, showing them between 9:00 am and noon and from 5:00 pm to 8:00 pm, using the slogan “Always Something Doing from 9 A.M to 11 P.M.”

By the early 1900s, the theatre had made a 180-degree turn from its relatively clean-cut past by fully embracing burlesque, having only dabbled in it before. The Old Howard quickly gained a reputation in polite society as nothing more than the go-to joint for tawdry strip-tease, but it featured major burlesque stars like Gypsy Rose Lee and Ann Corio, the latter being a favorite among Harvard undergrads – who raved regularly about her beauty and dancing skills in The Harvard Crimson – and later a film star, singer and author.

Comedy, Boxing demonstrations

The Old Howard balanced burlesque with comedy and a laundry list of legendary comedians appeared including W.C. Fields, Abbott & Costello, Jimmy Durante, Jackie Gleason, Al Jolson, Buster Keaton, Jerry Lewis and Fred Allen. Writing in 1912 about Boston and what one columnist called its “district of debauchery,” Allen said the city was “as proper and conservative as the high-button shoe” in general and Scollay Square was “the hot foot applied to the high-button shoe.”

In the years leading up to and after World War II, the theatre also featured onstage boxing demonstrations by and interviews with famous fighters including Rocky Marciano, a Brockton, Massachusetts, native known as the “The Brockton Blockbuster” who was world heavyweight champion from 1952-1956.

Closing, Howard National Theatre and Museum Committee

In November 1953, the Boston Police Department’s vice squad secretly filmed three strippers performing at the Old Howard, leading city censors to file indecency charges that banned future burlesque performances at the venue and the city to refuse renewal of its operation license due to the charges, resulting in the Old Howard shutting its doors forever by Christmas 1953.

The closing led to some confusion by some who came to Scollay Square afterwards looking for the Old Howard only to find the Old Howard Casino on Hanover Street, then owned by the same men who owned the Old Howard and named “Old Howard Casino” as a ploy to attract customers. The actual Old Howard remained empty for seven and a half years.

In 1960, Francis W. Hatch, a Harvard graduate who had frequented the theatre, established the Howard National Theatre and Museum Committee with the goal of raising $1.5 million (about $13.5 million in 2023) to completely refurbish the venue and turn it into a national museum, calling it “Boston’s most celebrated theatre” in an article published in Yankee magazine (“The Cathedral of Scollay Square: How Many Here Remember the Old Howard?”).

Fire, Conspiracy theories

While many people in the Boston area supported Hatch’s idea, all hopes were dashed on June 20, 1961, when a fire gutted the building. Conspiracy theories ran amok – and do to this day – about the cause of the blaze, despite the Boston Fire Department’s official conclusion that it was “of undetermined origin.” The fire happened at the height of Boston’s urban renewal initiative, when city planners were extremely reluctant to consider anything other than colonial-era structures “historic,” leading some to suspect that it had been ignited intentionally under the clandestine orders of Boston’s political elites.

Demolition, City Hall Plaza, Public response

In 1962, the city demolished the Old Howard and in 1963 it broke ground for the construction of Boston City Hall Plaza directly on top of what was Scollay Square, completing the project in 1968.

Public response to the plaza’s complete absorption of the area was largely negative at the time, and has tended to remain so into the 21st century as evidenced by a 2013 column in The Boston Globe. “It’s as if the complex’s architects vowed to make up for the bawdy sins of Scollay Square by creating a space that no one would ever want to congregate around,” it read. “The primary function of cities is clustering people together, but City Hall goes to great lengths to repel them.”

Original sign, Photo exhibition, Legacy

Few remnants of the Old Howard remain, but the legendary – some would say notorious – venue’s original sign is on display at the Emerson Arts Umbrella in Concord, Massachusetts. In 2020, Boston’s West End Museum premiered an exhibition of photographs, graphic panels and memorabilia celebrating the theatre. “Scollay Square and the Old Howard will always be connected to the history of the West End,” said Duane Lucia, the museum’s executive director and the exhibit’s curator, at the opening, calling the venue “a symbol of a bygone Boston deemed by the powers that be as incompatible with the vision of the ‘New Boston’ and urban renewal.”

In July 1944, an article in The Harvard Crimson described the Old Howard in a sympathetically lyrical way, citing its bawdy burlesque past and the loyalty of its patrons, both younger and older: “For years, the blue-lighted anatomical solos have brought the crowds past the box office. Once in a while, the long arm of the law reaches out to hold up a slipping brassiere or a drooping g-string, and occasionally competition has threatened the leadership of the Old Howard, but never did its loyal following of beardless youth and balded age fall away.”

(by D.S. Monahan)