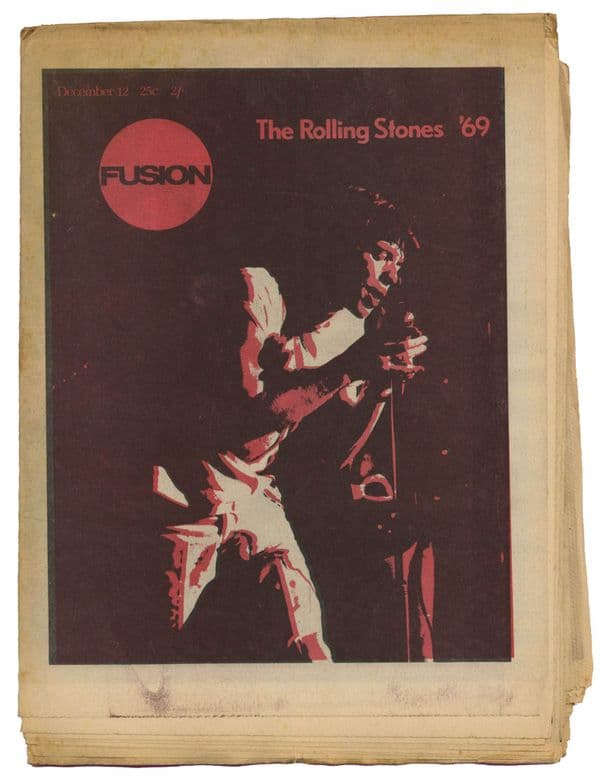

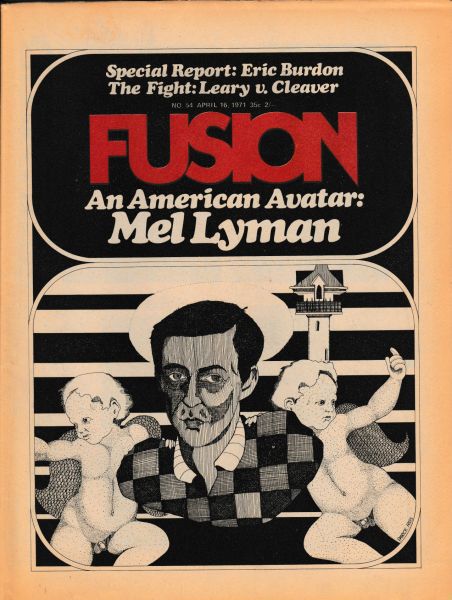

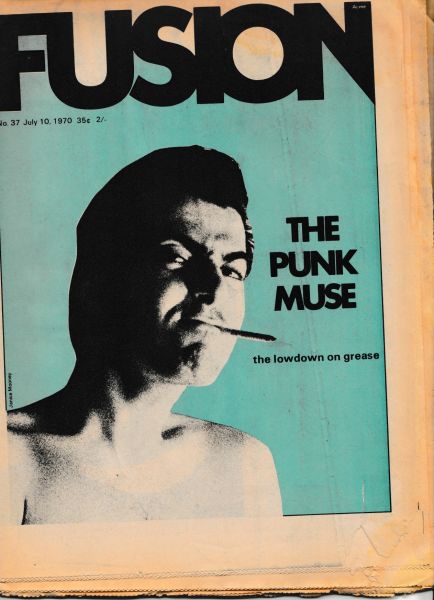

Fusion Magazine

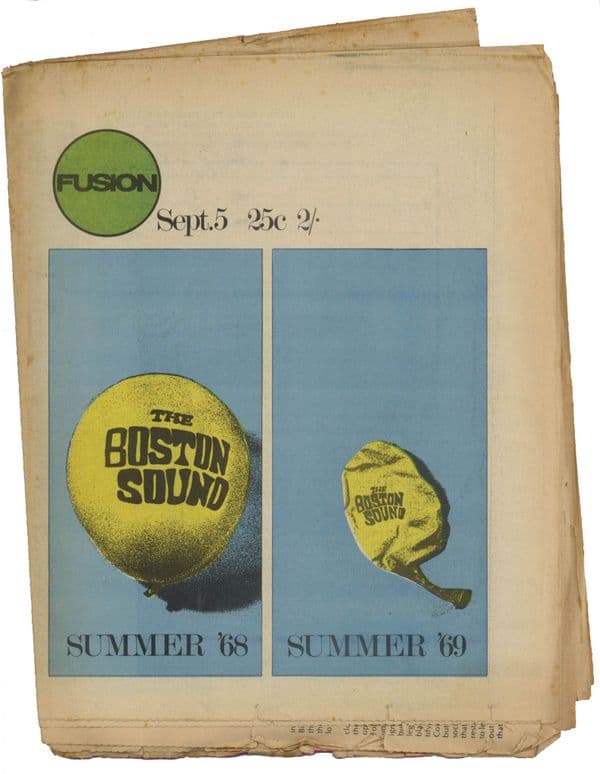

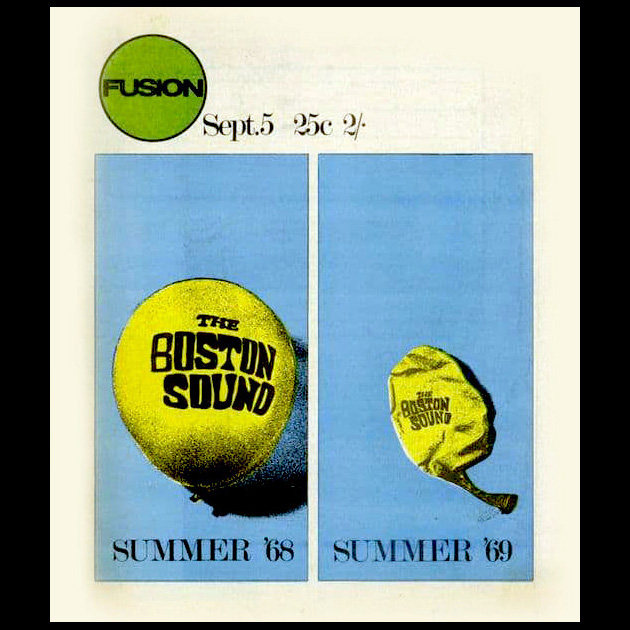

Witnessing the massive explosion of youth culture in his hometown of Boston, entrepreneur Barry Glovsky started publishing New England Teen Scene in 1966. The next year, inspired by the emergence of national rock mags Crawdaddy! and Rolling Stone, he and his Teen Scene colleague Ted Scourtis founded a new publication, Fusion, aspiring to expand their coverage both geographically and topically. After Walter Hitesman served as editor briefly, Glovsky recruited photographer Roswell Angier, a Boston University professor, and New York-based critic Bobby Abrams to edit the newly minted bi-weekly

For the next year or so, two sometimes contradictory strains began to emerge in the publication. First, there was the decision to take the burgeoning youth culture seriously as a subject worthy of critical analysis. The second was less of a decision than simply following the zeitgeist: promoting Fusion as a unique celebration of a sociopolitical revolution, with music in the forefront.

ROBERT SOMMA, ALBUM REVIEWS, CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

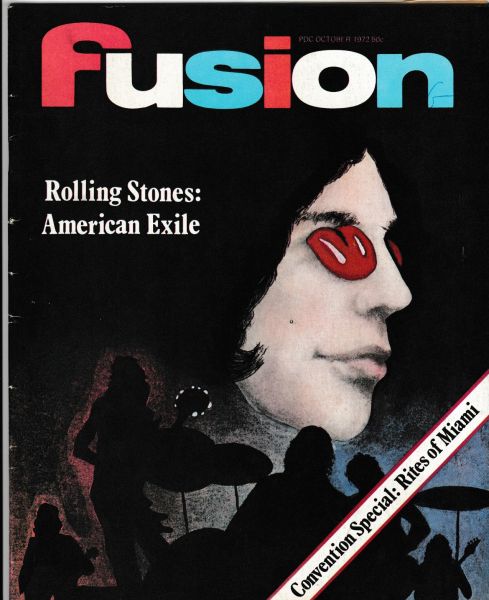

But it wasn’t until Robert Somma assumed the role of editor in September 1969 that the identity of the magazine crystallized. Fusion embraced the underdogs and the mavericks, in its hometown of Boston but also New York. In the pre-punk early ‘70s, Fusion devoted significant attention to New York trendsetters like The Velvet Underground and provided a platform for New York iconoclasts (notably R. Meltzer and Nick Tosches). Where other rock magazines generally held to the idea that the writing should be understood as being in service to the music, Fusion often used music and youth culture as jumping-off points for the writing about broader, sociopolitical issues.

Among the reasons readers gave for subscribing to Fusion was the album-review section. Established by the late Tim Jurgens and continued by the author of this piece, the critiques could be high-handed and irascible at time, but were generally informative and fair. Longer pieces on individual artists lent the review section an historical and analytical heft, often including full discographies. British writers Charlie Gillett and Simon Frith offered comprehensive examinations of the careers of notable rock artists; Peter Guralnick did likewise in the realm of the blues, R&B, country and rockabilly; Ken Emerson, Ben Gerson, Gene Sculatti, Lenny Kaye, Greg Shaw and others provided extended appreciations; and others included the late Jonathan Demme, before he became a celebrated film director, Rick Hertzberg, an editor at The New Yorker and The New Republic, and investigative reporter (and later performance artist) Paul Mills. The money was meagre and often came late, but Somma assured writers and photographers that the magazine would treat them respectfully in terms of credit, space and proof-reading and instilled a sense of being part of a worthy enterprise.

COMICS, COMMENTARY, COLUMNS, RONN CAMPISI, R. MELTZER

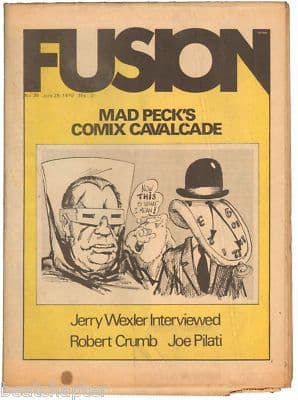

The Fusion review section also featured the comics and commentary coming out of The Mad Peck Studios in Providence, Rhode Island. The Mad Peck (aka John Peck) and I.C. Lotz (aka Vicky Hollmann) produced a unique visual element that was simultaneously retro and modern. Their idiosyncratic music and television reviews were told in six- or eight-panel cartoons, visual vignettes featuring a consistent cast of sarcastic characters.

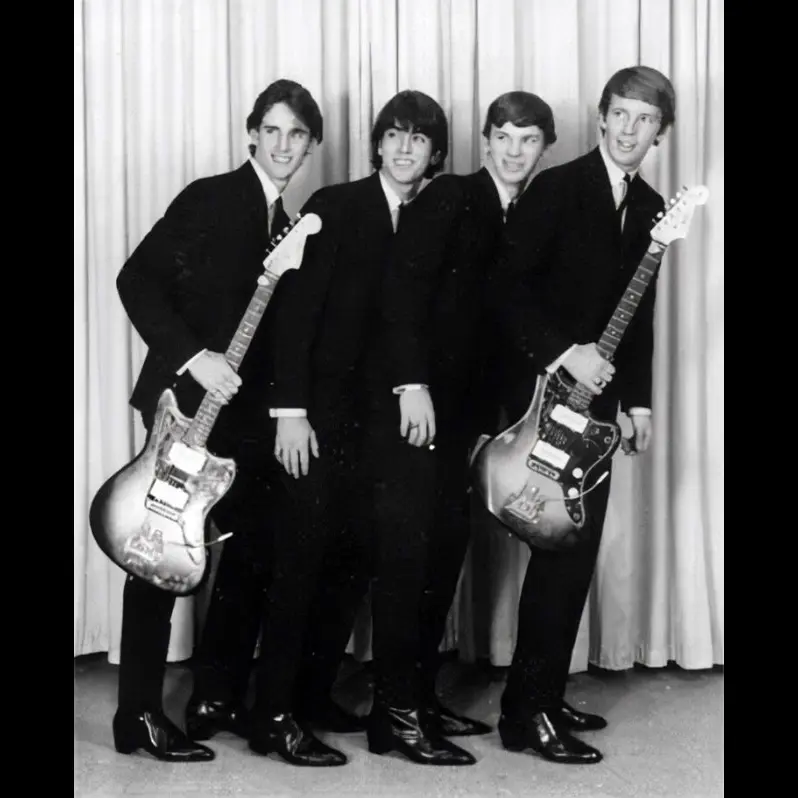

Under Somma’s leadership, several new columns appeared, including ones devoted to movies, politics, books, television, and sports. No account of Fusion can fail to recognize the contribution of Ronn Campisi, who turned to graphic arts after his local band, The Rockin’ Ramrods, failed to crack the big time. Unique among the art directors of other rock-oriented magazines, Campisi crafted a spare, modernistic design that echoed the wit and attention to detail of the writing. He went on to become the long-time art director for the Boston Globe.

In retrospect, one of Fusion’s greatest contributions may have been in providing a platform for R. Meltzer, perhaps the most original and outrageous writer to emerge from the rock press. Meltzer never considered himself a rock critic, but he reveled in a contrarian orneriness that would later dovetail perfectly with punk rock (he briefly fronted his own punk band, called Vom). His reviews and essays didn’t comment on rock ‘n’ roll – they were rock ‘n’ roll.

FEATURED ARTISTS, LEGACY

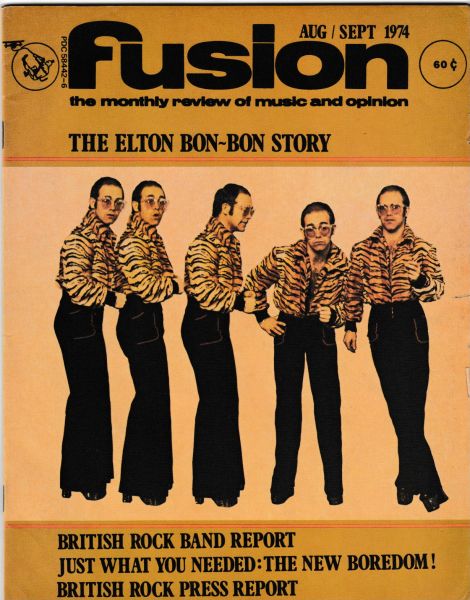

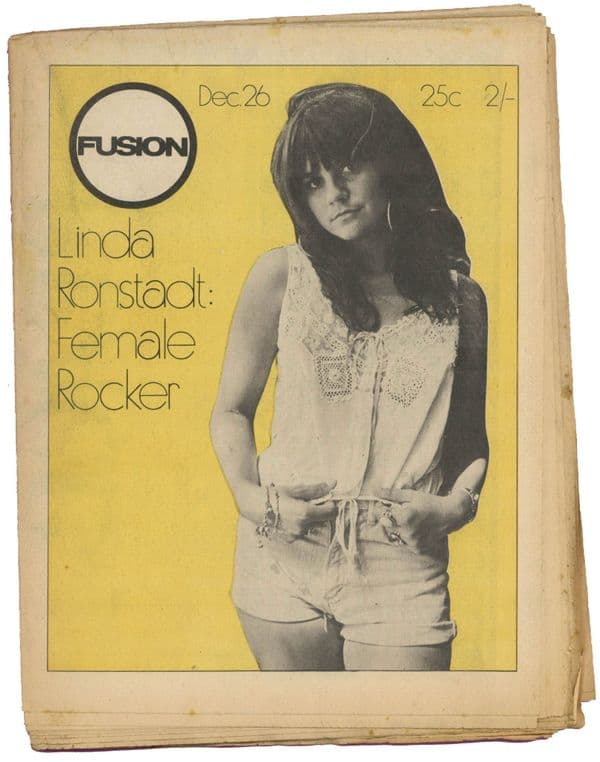

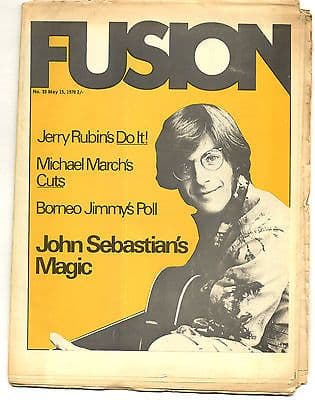

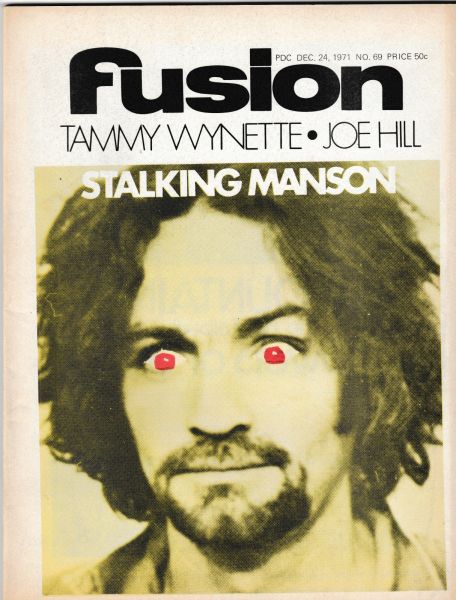

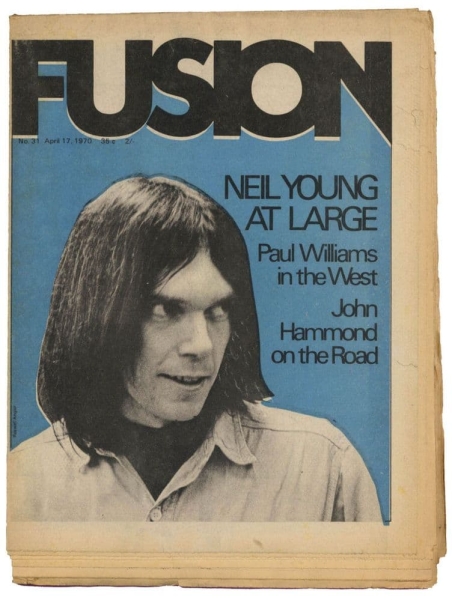

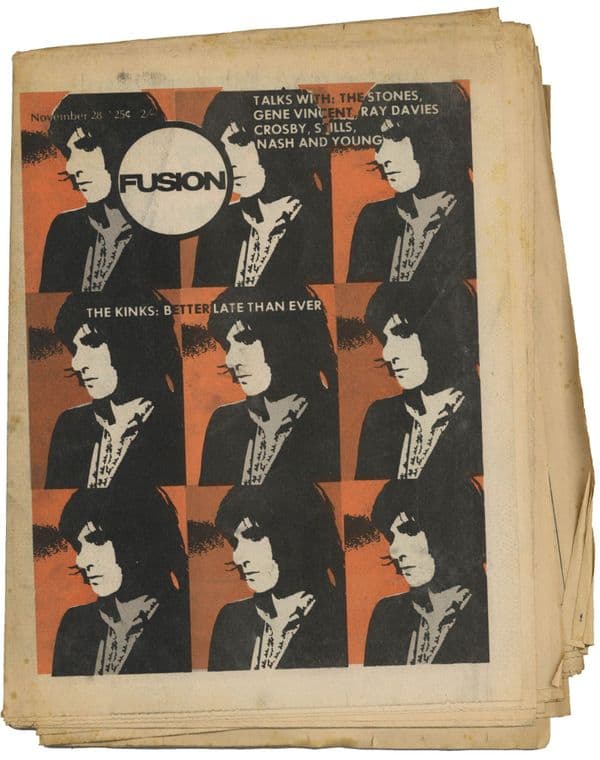

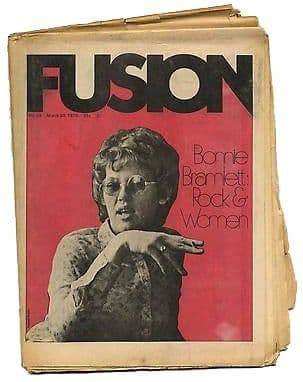

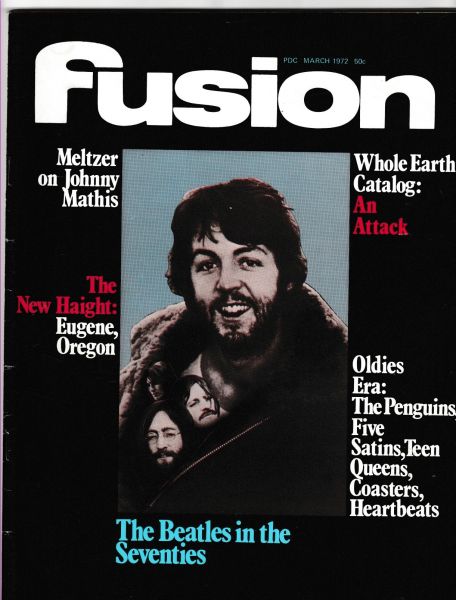

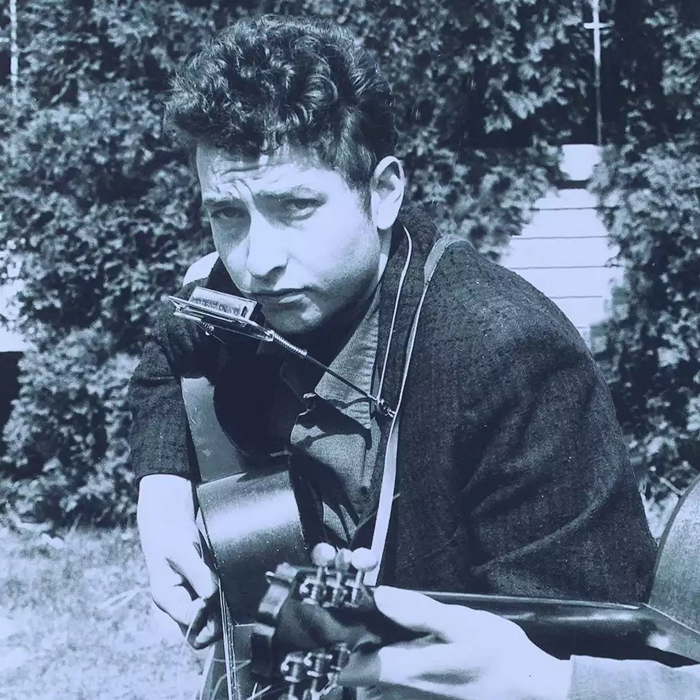

Fusion clearly had its favorites. In addition to The Velvet Underground, Fusion unapologetically championed the work of Bob Dylan, The Kinks, Van Morrison, Patti Smith and Neil Young, although excesses were not overlooked. Among the less-than-superstar artists who graced Fusion covers are Townes Van Zandt, Arthur Lee, John Sebastian, John Mayall and Bonnie Bramlett. Political figures such as George McGovern, Richard Nixon and Robert Kennedy also made it onto the cover, as did subjects such as television, drugs, party politics, health care, advertising and food.

These days, there are several other magazines called Fusion, including the online arts magazine of Berklee College of Music and Kent State University’s LGBTQ publication. Although the one in Boston never gained a large national audience during its seven years of existence (1967-1974), the narratives that emerged from its pages offered a compelling, thought-provoking account of the cultural revolution that happened in the city, other parts of New England and the greater US during the late 1960s and early ‘70s.

(by Gary Kenton)