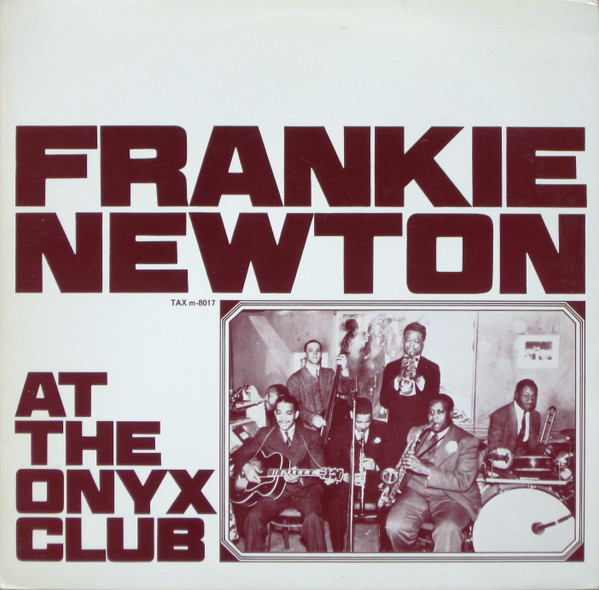

Frankie Newton

In 1942, George Frazier’s “Sweet and Low Down” became the first regular jazz column to appear in a big-city American daily newspaper, The Boston Herald. Frazier grew up in South Boston, attended Boston Latin School and went to college at Harvard, but he was disdainful of his hometown. “Boston Remains as Dull and Stupid as Ever” was the headline of an article he wrote in 1937 for DownBeat; he frequently referred to Boston as “the biggest small town” in America, saying there was “neither jazz nor excitement to be had” in the city after dark.

Frazier made few exceptions from the harshness of his criticism for local musicians, and one of them was Frankie Newton, a trumpeter who is largely forgotten today. Reviewing one of his records, Frazier wrote that Newton had reaffirmed “his right to be classed with the really top-notch trumpets of the day, for his swing, tone, taste, intonations, and inspirations are above reproach.” In 1937 Frazier said Newton was second only to Louis Armstrong among active trumpet players. Coming from a critic who acquired the nickname “Acidmouth” from his editors at DownBeat, praise like that really meant something.

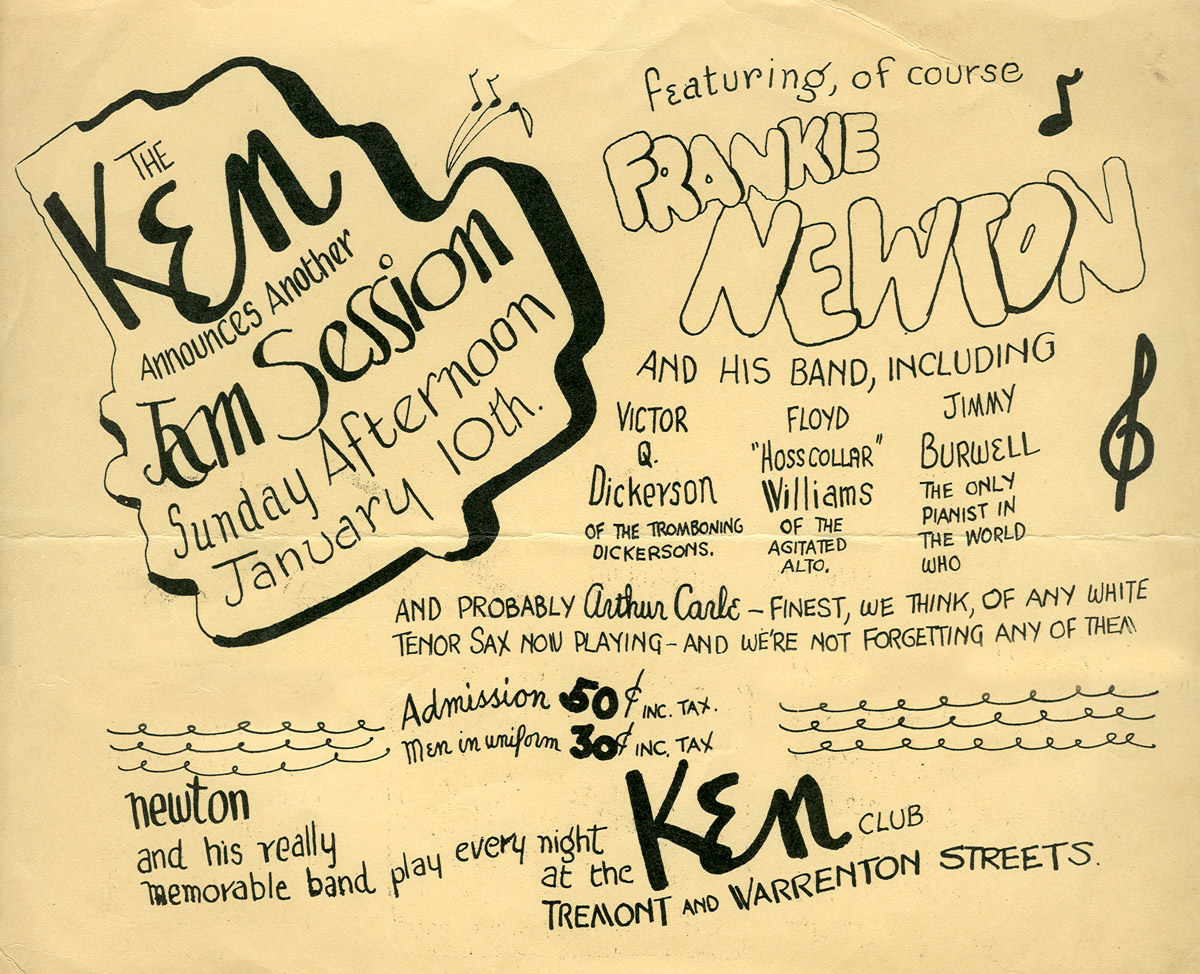

EARLY BOSTON APPEARANCES, “BOSTON’S FAVORITE TRUMPETER”

Born in 1906 in Emory, Virginia, Newton would spend a great deal of his 45-year career in Boston because his longtime companion and later wife Ethel was a native Bostonian. His first job connected to Boston was probably in the early ‘30s with Charlie Johnson, a saxophonist who grew up in the South End when it was known as “the Saxophonists Ghetto” because of all the practitioners of the instrument who lived there, including Johnson, his brother Howard and Johnny Hodges and Harry Carney, both of whom went on to play in Duke Ellington’s orchestra.

Newton led his own bands at various Massachusetts venues, including the Hotel Pilgrim in Plymouth and the Savoy in Boston, and performed in Boston with clarinetist Edmond Hall in 1949 and saxophonist Ted Goddard in 1947. He was the last jazzman booked at the Copley Terrace on Huntington Avenue before it closed in the summer of 1946, never to re-open. When the Boston Jazz Society – “an esoteric organization of sufferers from a mild form of jazz mania,” according to Frazier – attempted to present jazz in a setting more dignified than nightclubs (Huntington Chambers Hall), Newton was advertised as “Boston’s Favorite Trumpeter” on a 1946 bill with trombonist Vic Dickenson. The concert broke even, but the series itself was eventually disbanded; Boston wasn’t ready to accept jazz as America’s vernacular classical music.

CAREER HIGHLIGHTS, REPUTATION, COMMUNISM, DEATH, LEGACY

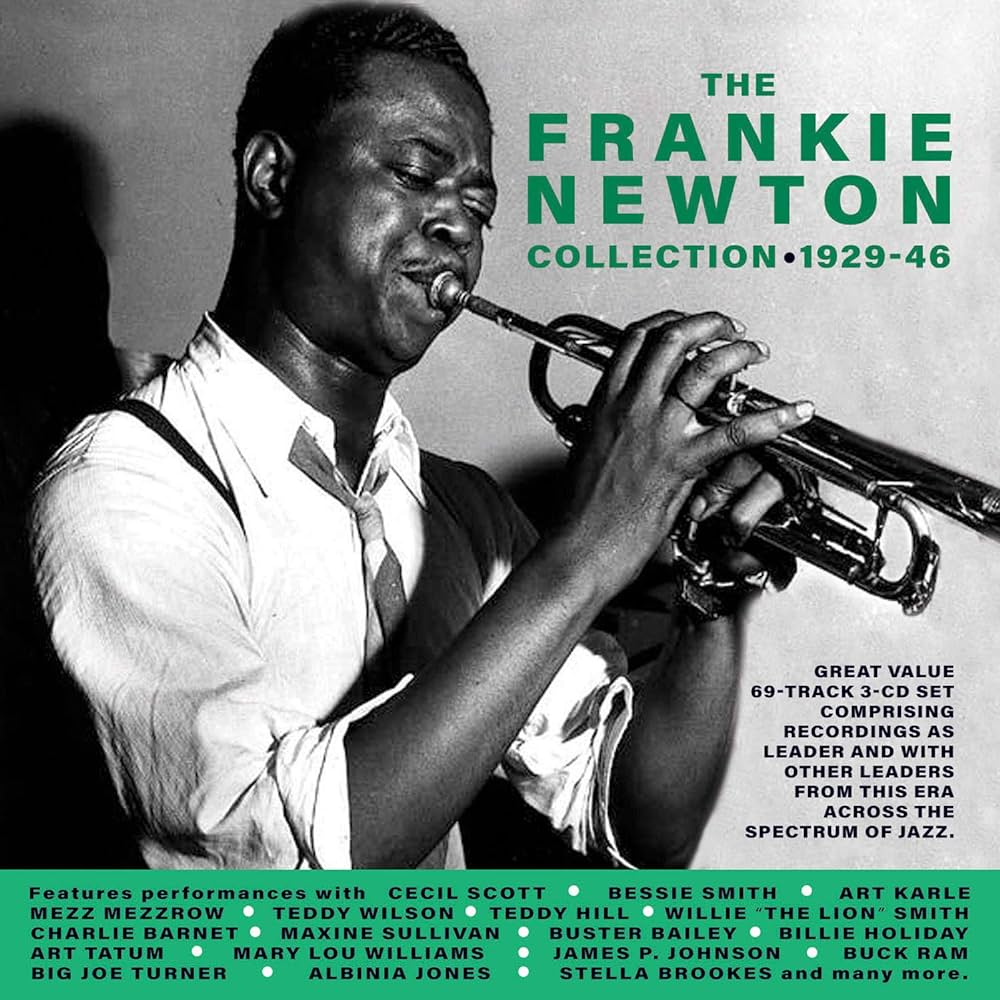

Newton’s career included two highlights that are milestones in the history of jazz. First, he played on Bessie Smith’s final recording session in 1933, along with Benny Goodman and other big names. Second, he was in the 1939 Billie Holiday session that included “Strange Fruit,” the anti-lynching song based on a poem by Abel Meeropol that’s often the only Holiday song known to those who aren’t jazz fans.

Competitors such as Charlie Shavers acknowledged that Newton “could play rings” around them, but Newton might have achieved greater success had he not had a reputation for being difficult to work with, having a short temper and letting strong opinions get in the way of long-lasting professional relationships. As famed jazz promoter George Wein put it, Newton “would burn bridges while he was still crossing them.” At a time when there was still some personal risk for a Black man in taking offense at verbal slights, he didn’t back down; when a Boston photographer acknowledged an act of kindness by Newton by saying “That’s mighty white of you,” Newton didn’t let it slide. “You mean that’s mighty BLACK of me,” he snapped.

A self-professed Communist, Newton was not averse to arguments that may have alienated him from fellow musicians, promoters and club owners, who could be expected to take a dimmer view of Marxist principles than his. Unlike the sort of musician who claims to speak for the common man while living in a tax haven, Newton lived his principles; the groups that he led were so-called “commonwealth” bands, meaning the members shared equally in the profits after expenses, even though a bandleader was customarily entitled to a bigger percentage.

However harsh he could be when offended, Newton was warm to those he counted among his friends. When white jazz critic Nat Hentoff began dating a Black woman, Newton became their unofficial bodyguard, accompanying them on their walks home from Boston clubs through both whites and Blacks who objected to interracial relationships. He gave freely of himself to the young, restoring old instruments for neighborhood children to play, and teaching them for free. Once when a young boy offered to pay him for trumpet lessons, Newton demurred, saying “Should I charge you by the note?”

Newton moved to Greenwich Village in 1952 and occupied his last years talking politics and painting. He made his last Boston appearance in 1953 and died of gastritis in 1954. His wife survived him and his grave is marked by a simple headstone that reads “Beloved Husband Frankie Newton – The Greatest.”

(by Con Chapman)

Con Chapman is the author of Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges (Oxford University Press, 2019), Kansas City Jazz: A Little Evil Will Do You Good (Equinox Publishing, 2023) and Sax Expat: Don Byas (University Press of Mississippi, 2025).