Charlie Holmes

Charles William “Charlie” Holmes is a bit of a musical enigma. Highly regarded in his time, he appeared on 130 recordings between 1929 and 1951, but only as a sideman, never as a leader. He once “cut” fellow alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges, a friend from his South End neighborhood in Boston, in a jam session, but turned down numerous offers to join Hodges in Duke Ellington’s orchestra. While Hodges and Harry Carney, another sax player from the South End, would go on to long careers and a measure of fame with Ellington, Holmes is largely forgotten today, a victim of chance and his own diffident personality.

MUSICAL BEGINNINGS, “SAXOPHONISTS’ GHETTO”

Charlie Holmes was born in Boston in 1910, the same year as Carney, who was his classmate at the Sherwin Grammar School in the Mission Hill neighborhood. The two received some musical instruction at the school, but Holmes didn’t think much of it. “They didn’t teach you nothin’. You weren’t being taught,” he said. Another friend from the South End, pianist James “Buster” Tolliver, told them about a youth brass band that a fraternal order, the Black Knights of Pythias, had formed, and they joined. Carney was assigned a clarinet while Holmes was given an oboe that he learned well enough to play with the Boston Civic Symphony Orchestra when he was just 16.

What they wanted, however, were alto saxophones, because of the influence of Hodges, who was three years their senior. “It just appealed to me when I heard him play,” Holmes recalled. Holmes acquired his sax in his junior year at Mechanical Arts High School in the Back Bay, and he and Carney began to gig around Boston with local bands led by Bobby Sawyer and Walter Johnson. Holmes said his grades “flopped because I was out at night playing any place I could for nothing, and running around different places with my horn under my arm, and get home at 2-3-4-5 in the morning, and then be in school at 8 o’clock. I’d go to school to sleep.

Holmes, together with Hodges, Carney and Howard Johnson (another friend from the South End), caused their neighborhood to be referred to as “Saxophonists’ Ghetto” because of the number of young practitioners of the instrument who were congregated there. Hodges began to travel to New York City to play in clubs, and told his friends about the greater opportunities for musicians there whenever he returned to Boston. “He would come back and when he’d get to playing, he would play all these different ideas and things,” Holmes said. And Hodges had a fat bankroll that he would flash to let them know that he was making good money, too.

MOVE TO NEW YORK CITY

When they were 17, Holmes and Carney decided to try their luck in New York on a whim. “There was a bunch of us, sitting in the ice cream parlor. All the little girls from Sunday school and all the hip boys,” Holmes said. “So one of them says, ‘Hey, let’s go to New York on the weekend. We can go to the Savoy Ballroom. Johnny Hodges is working there.” The two resorted to a ruse familiar to countless teens: Holmes told his mother that they’d be staying with friends of Carney’s mother, and Carney told his mother that they’d be staying with friends of Holmes’ mother.

While four young men thus signaled their ambition to take a bite of the Big Apple, only two – Holmes and Carney – followed through. They saw Hodges at the Savoy on their first night, then joined him and drummer Chick Webb for an after-hours jam session. When it came time for Holmes to take a turn, he demurred: “I’m not gonna do no playin’,” he said, but the others insisted. When he finished, somebody said to Webb, “He’s outswinging your man Johnny Hodges!” Their names began to get around with the help of Webb and Hodges, and the two began to pick up gigs in the city, first at an all-night masquerade ball, then with banjoist Henry Sapparo, a friend of Carney’s family.

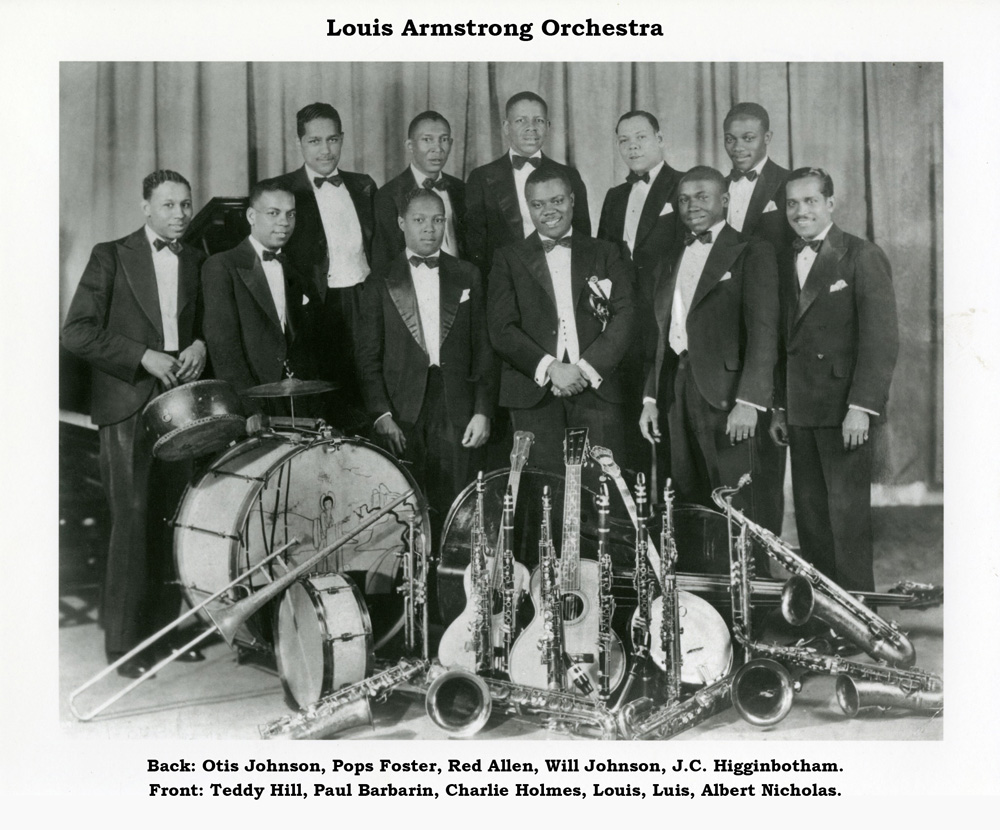

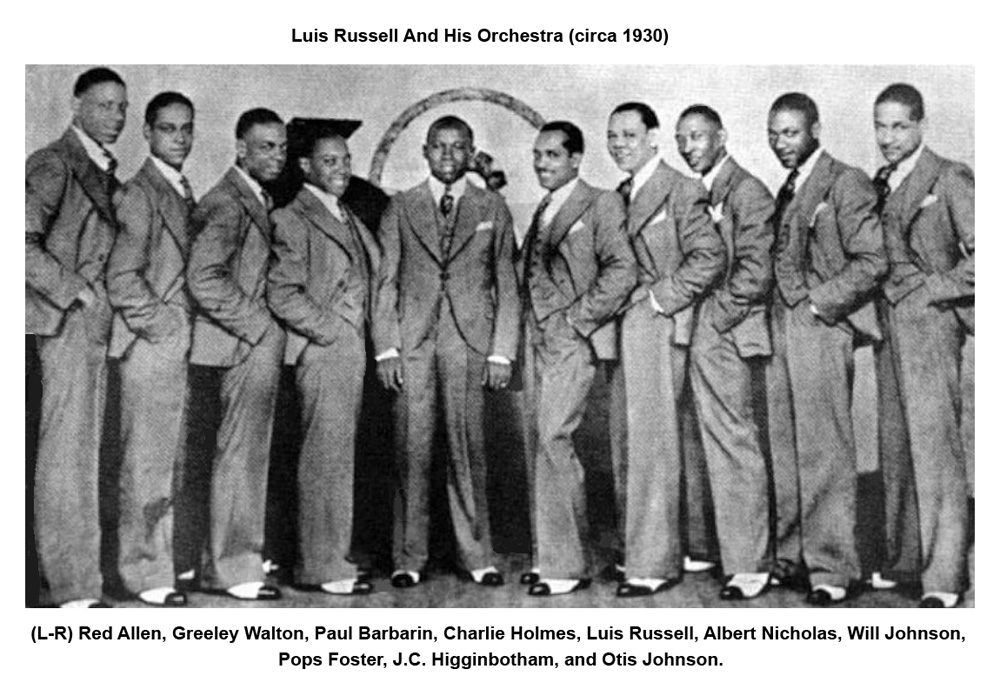

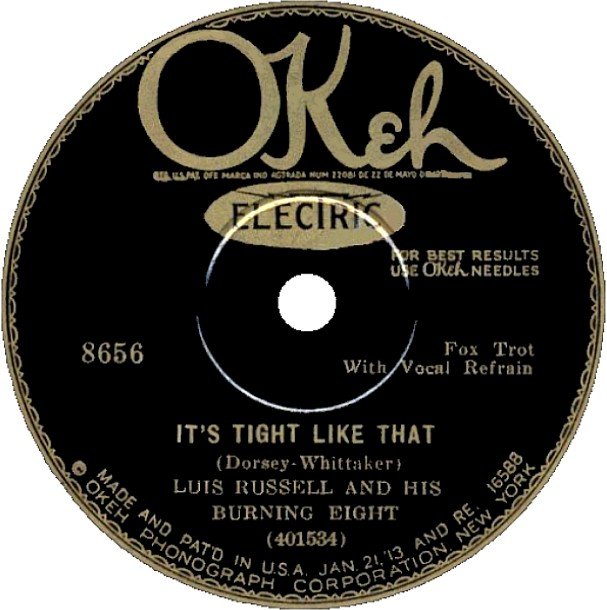

LOUIS ARMSTRONG, OTHER COLLABORATIONS, TURNING DOWN ELLINGTON

Holmes and Carney roomed with Ellington guitarist Freddy Guy, then Holmes was hired by Luis Russell while Carney joined Ellington’s band. Holmes recorded with Henry “Red” Allen and worked with Louis Armstrong, who gave him the nickname “Pickles” for reasons unclear. On the night that Holmes came back to Boston with Armstrong for a performance at Symphony Hall, Armstrong’s forgot his typical practice of introducing local members of his band when he was performing in their hometowns. After prompting, however, Armstrong said, “I’m sorry Pickles. Folks, we have one of your home boys here, Charlie ‘Pickles’ Holmes. Take a bow, Pickles.”

Holmes went on to work with Cootie Williams and toured the Far East in a USO show with Jesse Stone at the end of World War II. After playing with John Kirby and freelancing for a while, he left the music business and took a job with an insurance broker, gigging only on weekends. “I’ve been a loner practically all my life,” he said in a 1975 interview, and he suffered from low self-esteem as well. Ellington asked him to join his band 11 times, according to Holmes, but he turned him down each time. While Hodges had also turned Duke down, in the latter case it was the fear that his sight-reading skills weren’t good enough, which wasn’t true about Holmes.

In fact, Ellington’s band was Holmes’s favorite: “I loved to listen to the band. I was crazy about it,” he said, but he “never wanted to work with it. I don’t know why I desired to be with something not so good. You know, people have funny ideas. They know it’s not as good, but you don’t want to be with the best. One of them things, you know.” Holmes died in 1985 in Stoughton, Massachusetts.

(by Con Chapman)

Con Chapman is the author of Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges (Oxford University Press, 2019), Kansas City Jazz: A Little Evil Will Do You Good (Equinox Publishing, 2023) and Sax Expat: Don Byas (University Press of Mississippi, 2025).