Bill Leavitt

Berklee College of Music’s official website includes a section called “Berklee Faculty Pioneers” that features 11 educators who had a particularly profound impact on students and made especially unique contributions to the regional, national and international music communities. On the list are drummer Alan Dawson; pianist Everett “Dean” Earl; clarinetist John LaPorta; trumpeter Herb Pomeroy; saxophonist Joe Viola; composer-conductor Jeronimas Kacinskas; composer-conductor John Bavicchi; recording engineers Terry Becker Boyle and Robin Coxe-Yeldham; and former Berklee Provost Robert Share.

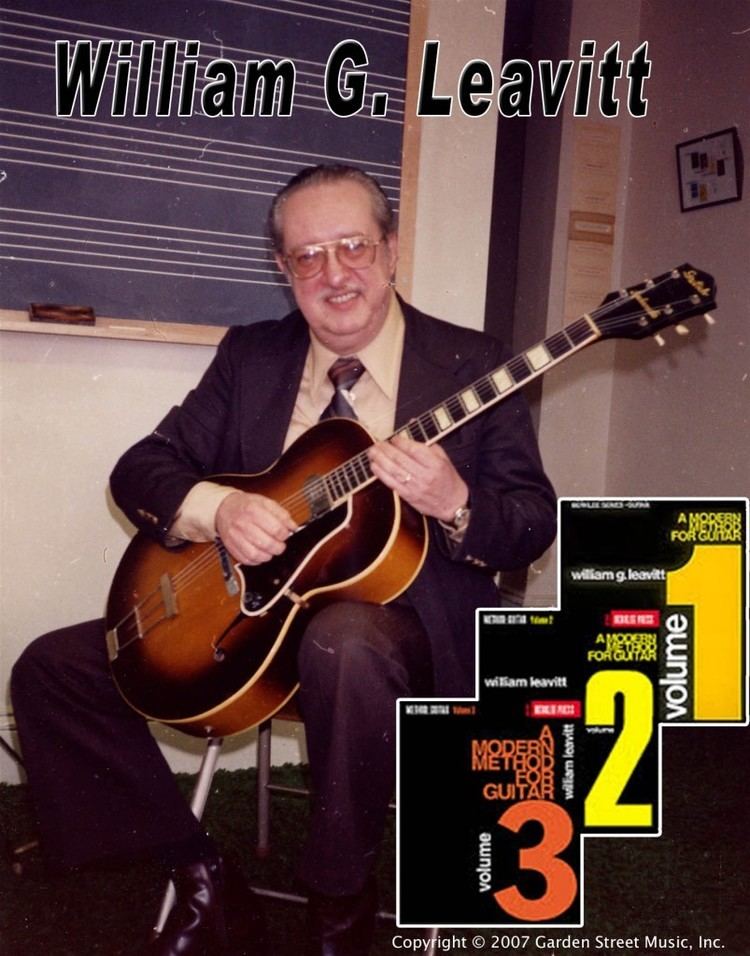

As careful readers will have noticed, there aren’t any guitarists in the paragraph above, but there is one on Berklee’s list: Willam G. “Bill” Leavitt, who’s widely credited with pioneering college-level pick/plectrum guitar education. During his 24 years chairing the school’s Guitar Department, he penned the three-volume series A Modern Method for Guitar and four other instructional books, all of which are staples at music schools to this day, while teaching hundreds of students including John Abercrombie, Bill Frisell, John Scofield, Mike Stern and Steve Vai. Before entering the educational arena, he’d written and/or arranged material for a number of celebrated singers, among them Ella Fitzgerald, Patti Page, Judy Valentine, Linda Doherty, Cindy Lord and Andy Williams, and co-written Les Paul and Mary Ford’s 1952 song “My Baby’s Comin’ Home,” which has been recorded by Paul Anka, B.B. King and others.

MUSICAL BEGINNINGS, NAVY YEARS, STUDENT YEARS

William George Leavitt was born October 4, 1926 and raised in Flint, Michigan. He began playing lap-steel guitar in his early teens but changed to a standard six-string in high school, playing in various local bands until mid-1945, when he enlisted in the Navy. After three months of basic training, he studied at the US Naval Radio Training School in Indianapolis, Indiana, completing the program in October 1945 and remaining in the Navy for the next three years.

During that time, he honed his chops and developed his style by playing in a dance band and a jazz trio with clarinetist Harry “Mike” Michael and drummer Allan Amenta; he also enjoyed drawing, particularly cartoons, and considered pursuing a career as a commercial artist, according to Michael. “Bill Leavitt was a wonderful guitarist at his age and a marvelous person,” he wrote in 1995. “He was a star even then, and playing with him was one of the high points of my life. In addition to his superb musicianship, Bill was a fine cartoonist and sketcher. With an eight hour-a-day schooling in radio operating and his dance-band and jazz-trio playing, it’s a wonder he found the time to sketch just about everyone in his class and to pen cartoons for the school newspaper and his class graduation album.”

In September 1948, 21-year old Leavitt moved to Boston to study at Shillinger House, founded in 1945 by pianist-composer Lawrence Berk and named after musicologist Joseph Shillinger, originator of the mathematics-based Shillinger System of musical composition. He was the third guitar student to enroll at the school and graduated in 1951; Berk renamed Shillinger House Berklee School of Music in 1954 (after his son, Lee Eliot Berk) and it became Berklee College of Music in 1970. Between the early ‘50s and mid-‘60s, Leavitt led orchestras of his own, recorded on Boston-based Tiffany Records, copyrighted more than 20 original songs including “Easy Going,” “Bach in the Old Chorale,” “I’ll Wait for You” and “Beguine Scene” and wrote and arranged for a variety of artists and radio programs.

BERKLEE FACULTY YEARS, PUBLICATIONS, TEACHING STYLE

In 1965, 29-year-old Leavitt replaced multi-instrumentalist Jack Petersen as the chair of Berklee’s Guitar Department, a position he held for the next two and a half decades. Peterson, who joined the faculty in 1962, designed the school’s first curriculum for guitar but Leavitt expanded it dramatically with his three-volume A Modern Method for Guitar series, which remains the gold standard for texts on pick/plectrum guitar techniques. Leavitt’s method provides a strong foundation in terms of reading, technique and harmony and its purpose is to train guitarists in fundamental skills, not in a particular style or musical genre. The books include standard notation, chord symbols and occasionally fingering numbers, string numbers and position numerals – none of them include guitar tablature – and range from beginner level to professional. The groundbreaking series received nearly instant acclaim among educators because college-level material on using a guitar pick, not a fingerstyle approach, was extremely rare in the ‘60s, even though many students used picks.

Leavitt’s curriculum outline for the series spanned four semesters (two school years), with volumes one and two being the focus of the first two and volume three being the focus of the last two. His method demanded that his students have exceptional sight-reading skills regardless of their improvisational ability, which made lessons tough for some of the hippie generation’s more improv-based guitarists, according to John Carlini, one of Leavitt’s students in the late ‘60s. “Bill was on a mission at Berklee: to provide competent, professional guitarists to the musical world,” he wrote on his website in 2020. “That meant being able to sight read and to know that fingerboard. It’s an entirely different thing than being a great jazz player/improvisor. Bill was successful in a world where ‘they’ put the music in front of you and you played it. Period. If you couldn’t read the part it was, ‘NEXT!’ Frankly, some students got it and some didn’t, but Bill never wavered from his position. And he was an inspired instructor.”

While he was notoriously strict about students following the guidelines in his books, Leavitt was also known for giving them his full attention both in and out of the classroom and “wrote the book on going above and beyond,” according to Carlini. “If I had a question or an issue at a time when I had no appointment, he’d buzz me in even if he was busy with another student,” he wrote in 2020. “He’d say, ‘Get back to me in 20 if you can’ and 20 minutes later, he’d be giving me his undivided attention as I poured out a musical or even some personal problem. Without fail, five minutes later I’d walk out of that office with a new and positive perspective. Bill had literally hundreds of students, but somehow he was never too busy to help any of them. I never left his office without feeling that I had just been given a wonderful gift, one that keeps on giving.”

Leavitt wrote four texts in addition to the A Modern Method for Guitar series: Melodic Rhythms for Guitar, Reading Studies for Guitar, Advanced Reading Studies for Guitar and Classical Studies for Pick-Style Guitar. Every example in the books is a Leavitt original except for some in Classical Studies for Pick-Style Guitar, which distinguishes them from dozens of other method books that include traditional folk songs, tunes from the Great American Songbook and other standards.

LAP STEEL TUNING INNOVATIONS, COMPOSITIONS, DEATH, LEGACY

In the mid-‘80s, Leavitt invented a new tuning for the six-string lap steel guitar (low to high: C#, E, G, Bb, C, D), which allowed him to play three and four-note voicings of the various complex chords found in many jazz standards. Over the next several years, he wrote over 70 arrangements of Hawaiian and jazz songs based around lap steel, according to current Berklee professor Mike Ihde. “Bill always liked to write chord solos for guitar of the jazz standards that he loved so dearly, so naturally that was the first area he explored with the lap,” he wrote in 2005 on the Steel Guitar Forum website. “He soon discovered how limited the standard tunings were for all the jazz voicings he was looking for, so he started experimenting with new tunings. He told me one day, that he had a dream about this diminished tuning and started working on it. When I last saw him at the hospital, two days before his death, he was still working on new arrangements.”

Leavitt died on November 4, 1990 in Framingham, Massachusetts at age 64; the cause of death was complications arising from chemotherapy he received as treatment for acute myelogenous leukemia. Soon after his death, Fender Guitar Company sponsored a memorial scholarship at Berklee that continues today, the William G. Leavitt Memorial Scholarship Fund. “I’ve always remembered Bill as the best guitarist I ever played with and one of the finest persons I have ever known,” wrote clarinetist Michaels of the trio Leavitt played in during his Navy years. “And it was no surprise to me that he went on to such an illustrious career and that he was so esteemed by so many.”

“He was a wonderful person and the best father and husband anyone could ever dream of,” wrote Melodee Hill, Leavitt’s oldest daughter, shortly after his death. “He had a wonderful laugh that could pick up your day no matter how bad it was going and was kind to everyone. He had time to listen to you no matter how busy he was. I have a box of letters, perhaps 100 or more, from students, prisoners and soldiers whose lives he touched with either his music, teachings, letters or private chats, thanking him for his help and kindness.”

(by D.S. Monahan)