Sonny Stitt

One of the most prolific jazz musicians ever born in Boston was a man who came into the world with a name that, oddly enough, wouldn’t have looked out of place on the membership list of an exclusive Beacon Hill men’s club. Edward Hammond Boatner, Jr., better known as Sonny Stitt, appeared on over 100 albums as leader or sideman in his four-decade career, but he struggled for much of that time to emerge from the long shadow of Charlie Parker, whose innovations on the alto sax changed the way not just that instrument was played, but all of jazz.

Early Years

Stitt is associated with Boston because he was born there in 1924, but he spent little time in the city. He was given up for adoption almost immediately by his father, a composer and opera singer who wrote concert arrangements of Negro spirituals. While that seems cruel, as Mark Twain said of Wagner’s music, it’s not as bad as it sounds; his mother, Claudine Thibou of Cambridge, moved with her son to Saginaw, Michigan, where she married Robert Stitt, and the boy was known by that surname thereafter.

Musical Beginnings

At Central Junior High School in Saginaw, Stitt was called “Edward” but he eventually adopted the nickname “Sonny,” by which he would be known professionally in place of his stilted-sounding given name. He started playing alto sax professionally while still in high school with The Len Francke Band, a local swing group, then moved on to a bigger name, Tiny Bradshaw, a singer best known today for the original version of “Train Kept A-Rollin,’” covered (with less swinging rhythm) by The Yardbirds and Aerosmith.

Charlie Parker Comparisons

In 1943, Charlie Parker, three and a half years Stitt’s senior, heard him play and said, “Well I’ll be damned, you sound just like me.” Stitt replied, “I can’t help the way I sound. It’s the only way I know how to play.” Others would have the same reaction over the years, but for a generation of alto-sax players it was difficult to escape the powerful influence of Bird’s innovations. For two bands – Billy Eckstine’s and Dizzy Gillespie’s – Stitt was in fact hired to replace Parker when the latter left. Stitt claimed to have developed his boppish approach before he heard Parker, which is possible but seems unlikely. He chafed at the suggestion that he was just a copycat of Parker, and the ferocious opponent he became in jam sessions may have been the product of a desire to prove himself.

Art Pepper Recollection

And prove himself he did. Art Pepper, a man capable of breakneck speed and inexhaustible invention on the alto, recalled a club date one night in San Francisco when Stitt, passing through town with the Jazz at the Philharmonic tour, asked if he could sit in. Stitt went first, taking forty choruses, and Pepper, wasted on booze and heroin and in the middle of an argument with his girlfriend, dug down deep and played what he thought was one of the best impromptu solos of his life. Like a boxer disdaining his opponent’s hardest punch, Stitt merely nodded at Pepper and said, “All right.”

Incarceration, Addictions

Eventually, Stitt seemed to find peace by moving on; he was jailed for more than a year on a narcotics charge and when he was released from prison he added tenor and baritone saxes to his arsenal, in addition to alto. Freed from the burden of being The Next Bird, he recorded a number of pleasing albums in a variety of non-bop contexts. Once he kicked heroin in the late 1950s, Stitt turned to drink for solace and it eventually took its toll on him. He suffered a series of alcohol-related seizures and eventually gave up booze as well.

Competitive Drive

Following his release from prison, Stitt retained his formidable technique, unlike some altos (Frank Morgan comes to mind) who returned from addiction and incarceration with diminished powers. For the most part it can be said that he kept his competitive drive in check, never subordinating melody to virtuosity, but there were lapses. At one Jazz at the Philharmonic concert where he shared the stage with Lester Young, Stitt appeared to go out of his way to impress Young, one of his early idols. When Stitt sat down after finishing his solo, Young – the man who first used the word “cool” as an expression of praise – calmly looked at him and said, “That’s nice, but can you sing me a song?”

Miles Davis, The Giants of Jazz, Gene Ammons

Stitt played briefly with Miles Davis in 1960 and he can be heard on a few live albums from that period, but Davis fired him for excessive drinking. In the seventies, Stitt was part of an all-star group called The Giants of Jazz which also included Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie and Art Blakey, and he made a number of well-regarded albums with Gene Ammons in an unusual double-tenor sax setting.

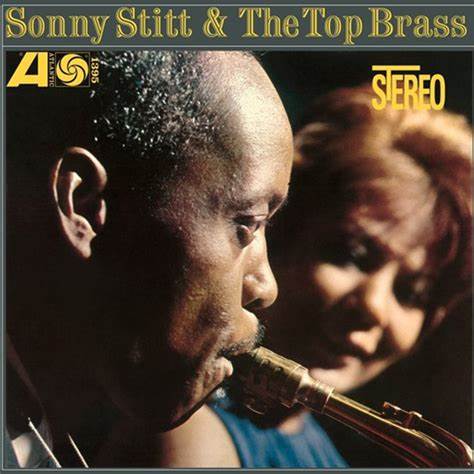

“Stitt in the Studio”

We have one account of Stitt in the recording studio, “Stitt in the Studio” by Martin Williams, a jazz critic and the former head of the American Culture program at the Smithsonian Institution. On the occasion of a 1962 session that resulted in Sonny Stitt & the Top Brass, Williams said of Stitt that while he lacked Charlie Parker’s “brilliance and his daring quickness of imagination in rhythm, harmony, and melody,” he “nevertheless is not playing an imitation, and his work is far from pastiche or popularization. He simply finds his own voice in Parker’s musical language.” On its face, that seems like a contradiction, which Williams recognized: “By almost all we profess to believe about jazz, it cannot be,” he wrote, “but it is.”

Death, Legacy

In 1982, Stitt was diagnosed with cancer and he died on July 22nd that year in Washington, DC. In a final insult, the headline of his obituary in The New York Times read “Sonny Stitt, Saxophonist, is Dead; Style Likened to Charlie Parker’s.” Parker had preceded Stitt in death by a quarter of a century and Stitt was a worthy if somewhat reluctant heir, wearing the alto crown uneasily, like Shakespeare’s Henry IV. Theirs was a friendly rivalry, however; when the two spoke near the end of Parker’s life, Parker told Stitt he was handing him “the keys to the kingdom.”

(by Con Chapman)

Con Chapman is the author of Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges (Oxford University Press, 2019), Kansas City Jazz: A Little Evil Will Do You Good (Equinox Publishing, 2023) and Sax Expat: Don Byas (University Press of Mississippi, 2025).