Saved by Rock ‘n’ Roll

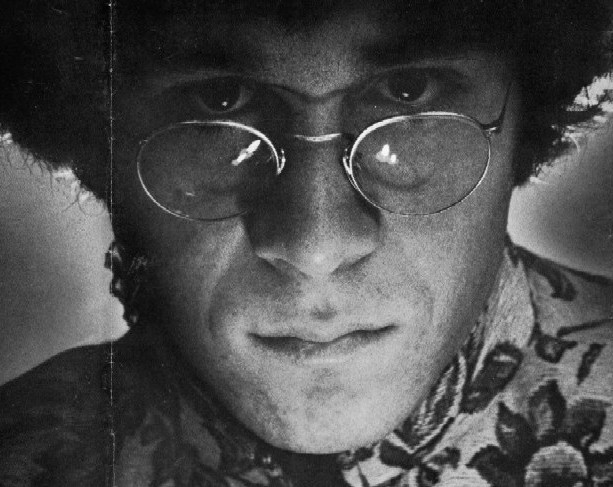

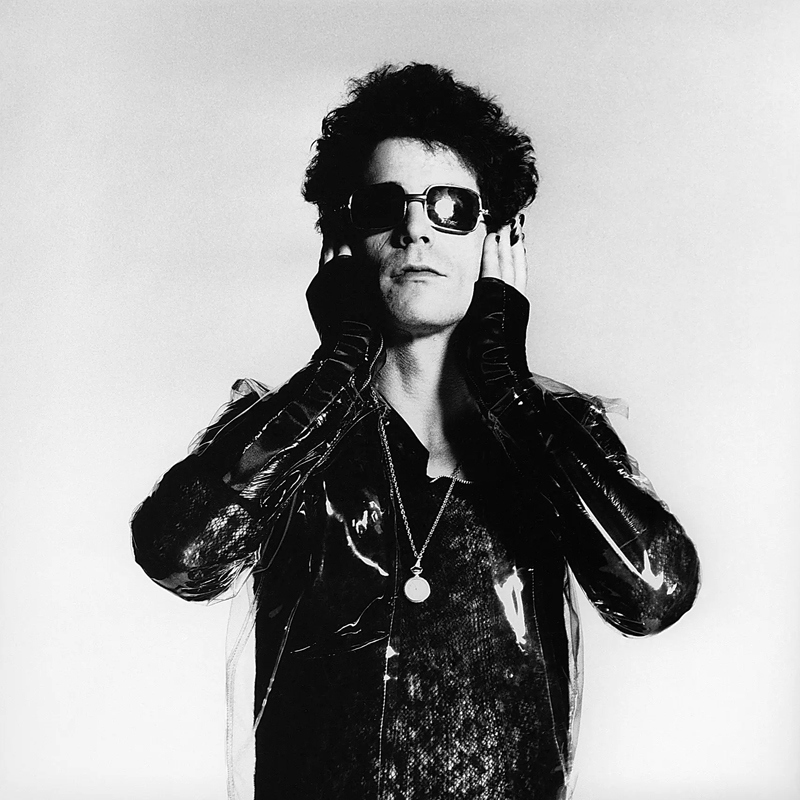

Lou Reed 1975 - photo by Mick Rock

LOU REED, THE VELVET UNDERGROUND AND THE BOSTON TEA PARTY

“She started dancin’ to that fine, fine music.

You know, her life was saved by rock ‘n’ roll, yeah, rock ‘n’ roll.”

“Rock ‘n’ Roll”

The Velvet Underground, Loaded

Words and music by Lou Reed

So was mine, saved by rock ‘n’ roll, and The Velvet Underground.

In the spring of 1967, I was a draft resister. A recent graduate of Harvard Law School, I had left my government job in Washington and returned to Cambridge, living on the edge while using my legal skills to prevent the Selective Service System from sending me to Vietnam.

At law school, we were reminded of the old adage, “He who has himself as a lawyer has a fool for a client.” Well, I was the only lawyer I could afford, but the process of representing myself, in what I felt was a life-and-death situation, left me physically exhausted and emotionally adrift. But in late May, I washed up on shore when I reached my 26th birthday. That meant I was automatically reclassified as no longer subject to be drafted. To celebrate, I took the T to The Boston Tea Party, a popular psychedelic-rock club and hippie hangout.

Headlining that night was The Velvet Underground. I had seen them play a year before at a private party in New York City thrown by the literary journal The Paris Review at The Village Gate. I did not run in those literati circles, but my girlfriend at Radcliffe College (who later became the author Beth Gutcheon) got a couple of invitations from a friend at Harvard (today the film director James Toback), so off we went to be greeted at the door by the Review’s founder and editor-in-chief, George Plimpton.

The Gate had three floors. We spent most of the night in the lower level, where several bands played nonstop. The last one came on well past midnight. I never heard them introduced, but was blown away by their instrumental intensity and pounding rhythm, as well as the strobes and other lighting effects. We just danced and danced. At one point, I saw Frank Sinatra coming down the stairs, but he quickly retreated from the cacophony and chaos in the room.

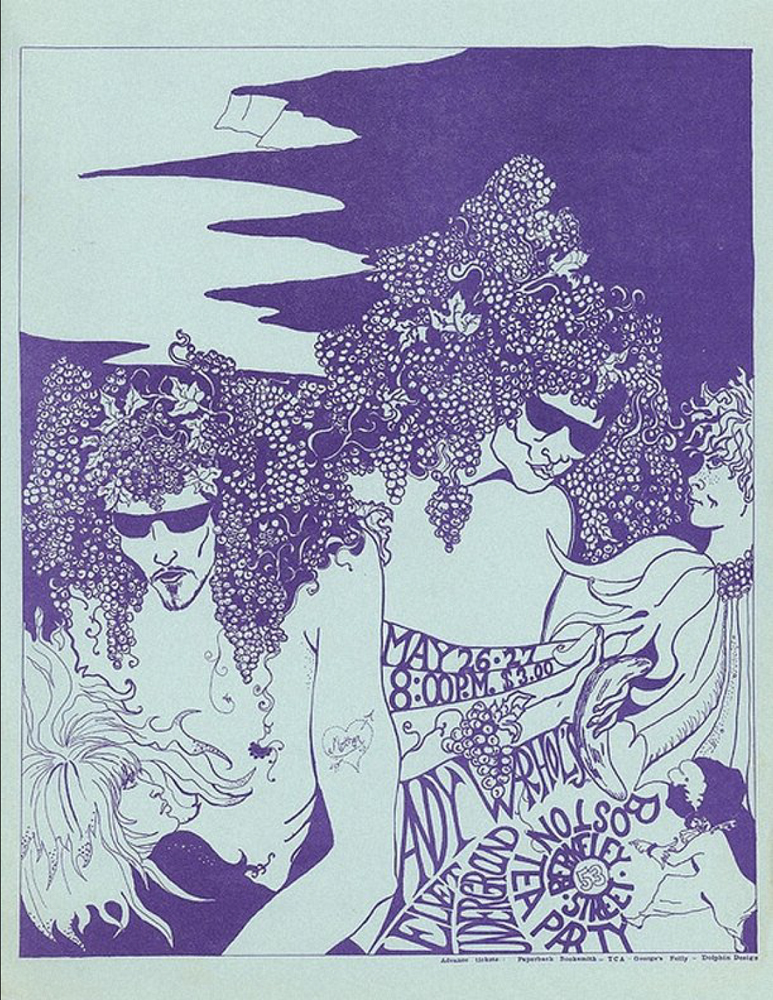

I never did find out that night who that band was, but their music was unforgettable. A year later, I spotted a new album in the record section at the Harvard Coop, The Velvet Underground & Nico, and finally discovered who they were, so I wasn’t going to miss their show at the Tea Party. It turned out to be an important step in their musical careers, because they had just separated from Andy Warhol and it was their first gig as a straight-out rock ‘n’ roll band, not just part of Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable multimedia freakout.

While at the Tea Party that night, I met one of the two owners, Ray Riepen, a lawyer from Kansas City who was doing a year of graduate work at Harvard. After the show, he gave me a ride home to Cambridge and we chatted about the club, the music scene and our common Harvard connection. He got involved with the club through a friend in Boston who was the daughter of Thomas Hart Benton, the renowned painter from Missouri.

I was barely surviving at the time, working in a leather and sandal shop near Harvard Square. A couple of months later, Ray looked me up there, told me he was thinking of buying out his partner and said that if he did, he would need someone to manage the club. I guess he figured that with my law background and long hair, I could handle it. He had also approached Jim Rooney, manager of Club 47, who decided to stay there. So when Ray offered me the job, I jumped at the chance. On my first night at the Tea Party in my new role, Country Joe & The Fish headlined and sang their infamous anti-Vietnam War song “Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag.” I was home.

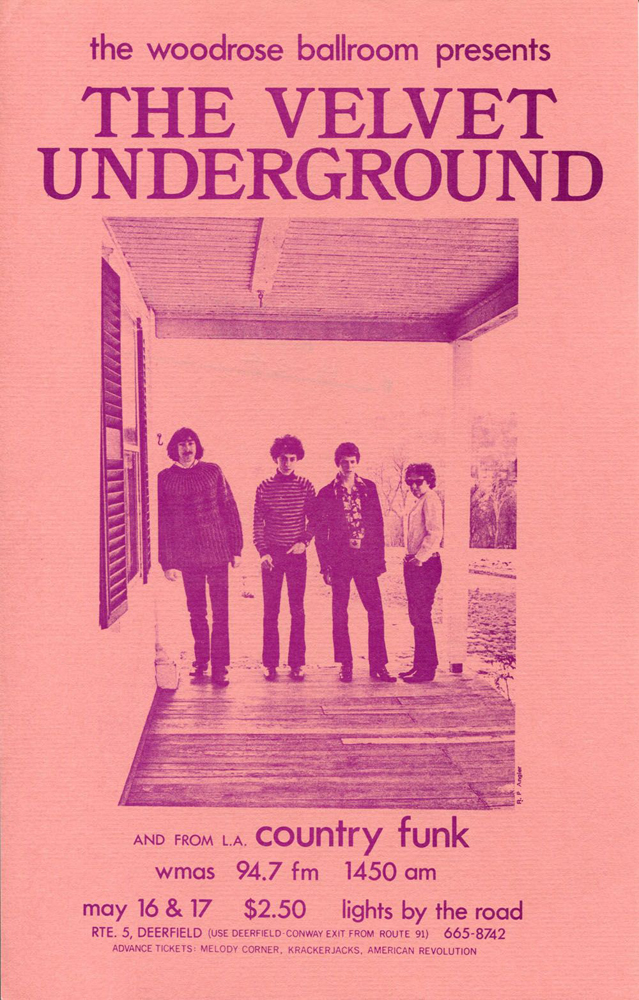

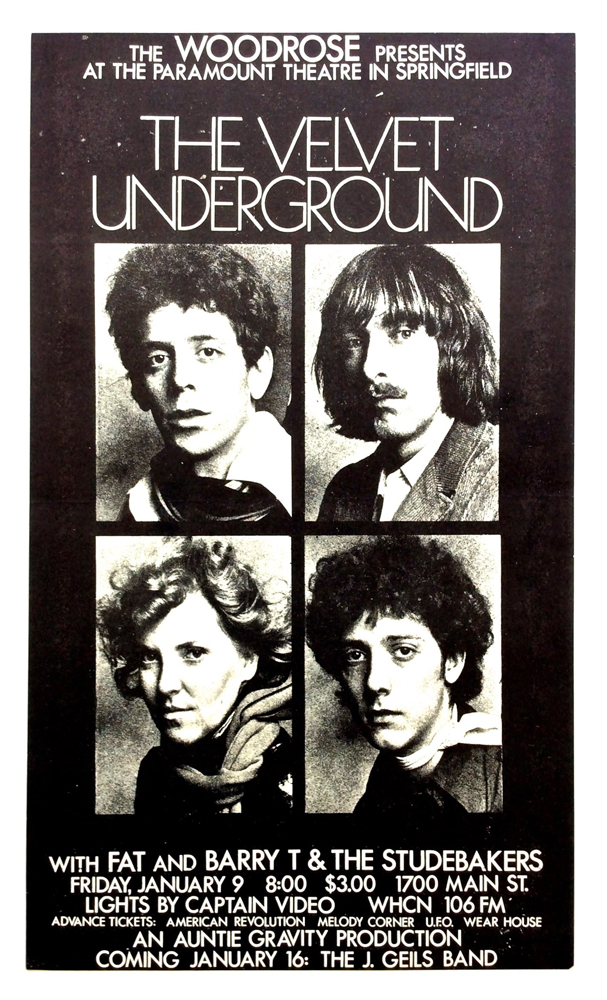

I stayed in the music business for less than three years, but during that time I booked The Velvet Underground many times, first at the Tea Party and then in Western Massachusetts at The Woodrose Ballroom in South Deerfield and at The Paramount Theatre in Springfield. I believed in the Velvets and their music, and they developed a strong following from those gigs. In fact, during that period they did not play in New York City (until their last gig together in the summer of 1970 at Max’s Kansas City). In effect, Massachusetts was their musical home base.

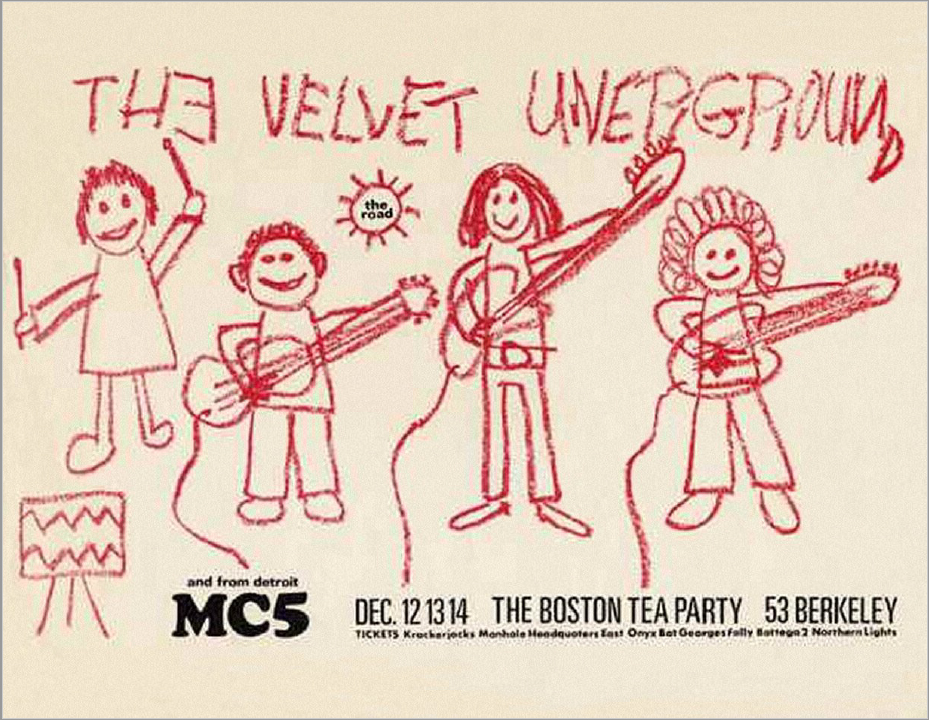

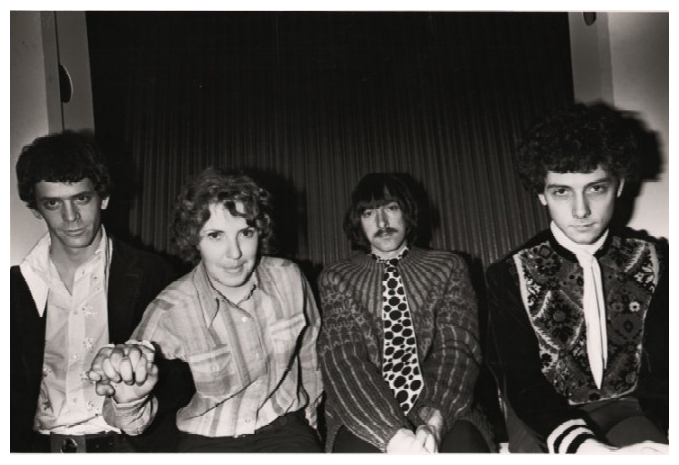

I got to know them as people and friends, behind their notorious public image. When they played a date at the Tea Party in December 1968, I designed the poster promoting the show and depicted them as childlike stick figures in a band. When I showed it to Lou Reed, he asked, “How did you know that’s who we really are?” I’d been around them enough to know that at heart they were four friends having fun playing rock ‘n’ roll together.

I lost contact with Lou and the other Velvets after I left the music business, but continued listening to their records and his solo work. I reconnected with him in the early 2000s and was his guest for a gig at the Calvin Theatre in Northampton. It was a special show for me, because the theatre was literally on the same road and just a few miles south of where the Woodrose had been. In the dressing room afterwards, Lou introduced me to his band members and explained who I was, saying “without him, The Velvet Underground wouldn’t have survived.”

And without them, neither would I. Thanks, Lou.

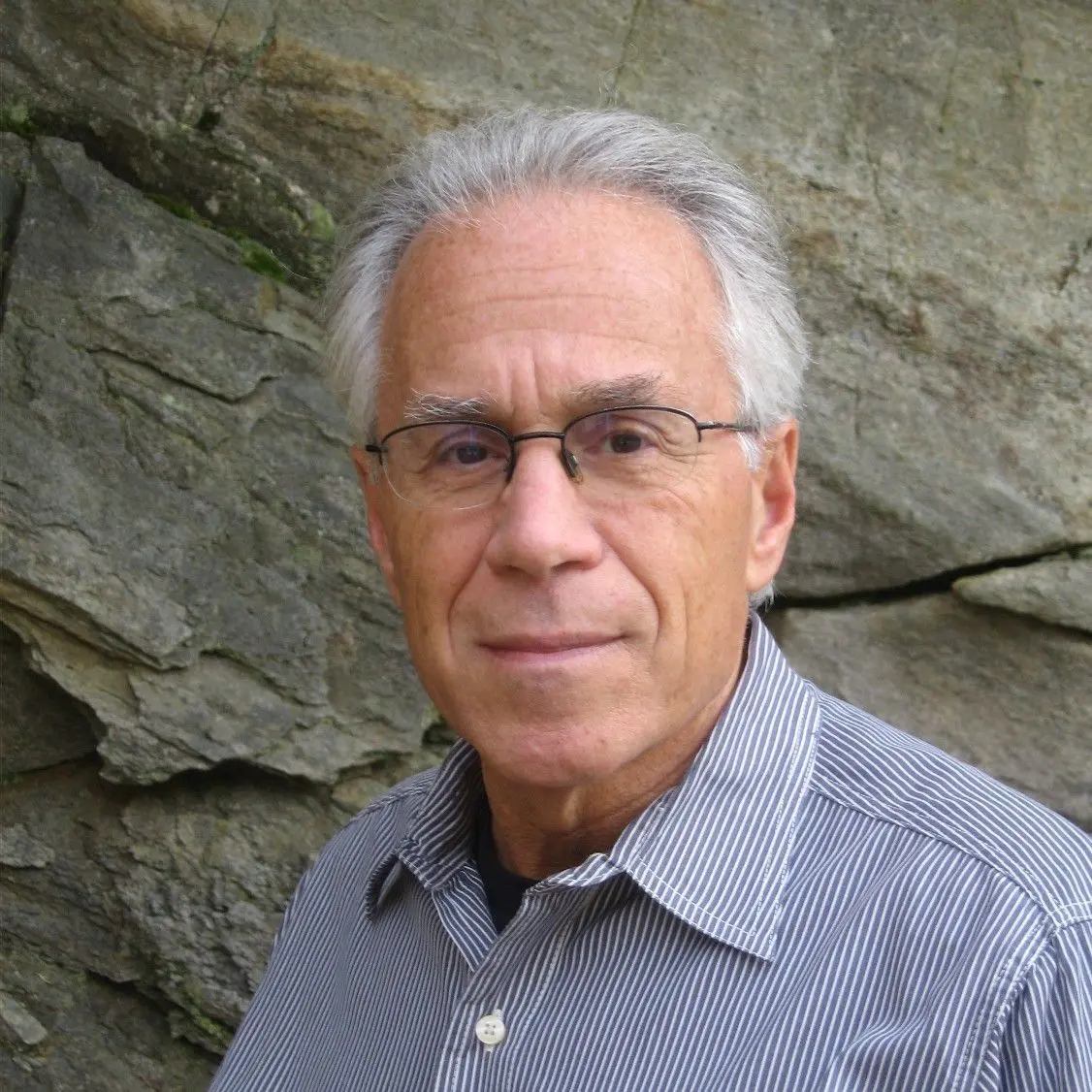

(by Steve Nelson)

Steve Nelson co-founded the Music Museum of New England and is the author of Gettin’ Home: An Odyssey Through the ‘60s.