Charles A. Stromberg & Son

Demand for guitars was booming at the start of the 20th century and the US had no shortage of manufacturers creating innovative, attractive and playable products, among them Gibson in Michigan; Gretsch and Epiphone in New York City; C.F. Martin in Pennsylvania; Harmony and Washburn in Chicago; Regal in Indiana; and Stella in New Jersey. In the 1920s, the rise of radio and availability of a wider variety of genres on 78-rpm records led to musical tastes changing faster than ever, and each maker tried to introduce models that would suit the latest trends while becoming premier examples of their kind in the long run.

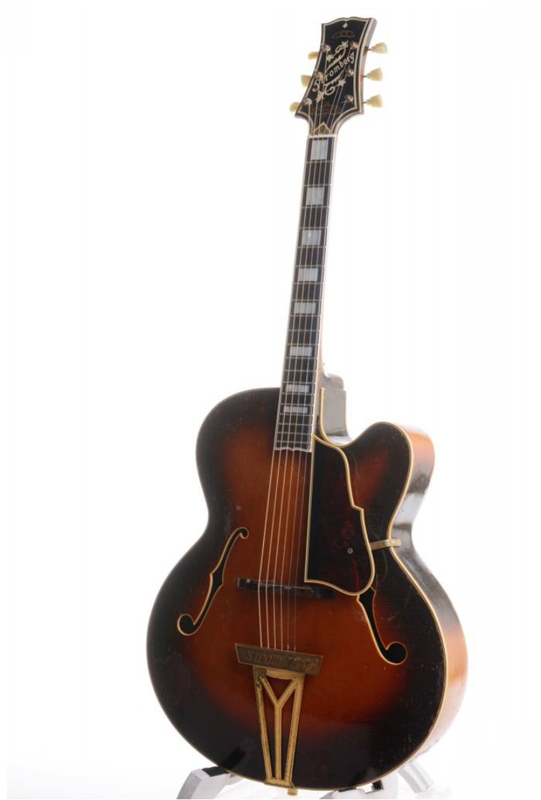

And in 1927, Charles A. Stromberg & Son began making ones that did exactly that. Though the Boston-based company produced guitars for just 28 years and made only about 640 in total, Strombergs are renowned for their superb quality and ability to “cut through the mix” – thus their nicknames, “orchestra cannons” and “trombone cutters” – and the G Series, Master 300 and Master 400 models were pivotal in the development of later jazz guitars, according to Gruhn’s Guide to Vintage Guitars. “In the world of archtop guitars, the Stromberg name represents the ultimate instrument in the big-band era of the late 1930s and ’40s,” wrote George Gruhn and Walter Carter in Vintage Guitar magazine in 2009. “The huge 19-inch Master 400 and Master 300 models are worthy of their flagship status as the best-known and most revered Strombergs. However, the smaller, short-scale G-5 cutaway from the ’50s may be equally important, not only in the context of Stromberg history, but in the overall history of the guitar.”

BACKGROUND, FOUNDING

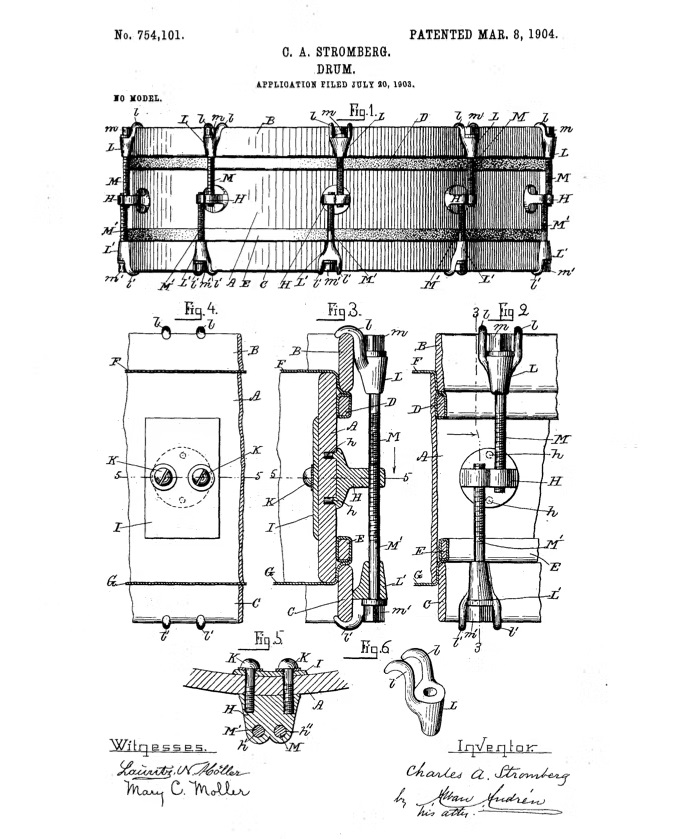

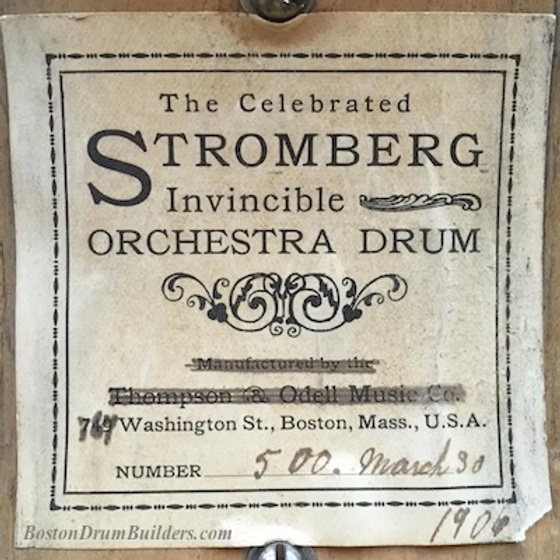

Stomberg emigrated to Boston from Sweden in 1887 and spent the 18 years before founding his company working as a foreman in music publisher and instrument maker Thompson & Odell’s banjo, mandolin and guitar factory, supervising the production of some 3,500 of those instruments. He started making drums for the company in the 1890s and was awarded two patents related to snare drum construction, the first in 1903 for a tension lug and the second in in 1904 for a snare-tightening device. Stromberg designed his Invincible Orchestra Drum in 1903 while employed at Thompson & Odell and it became a central element of his own product line two years later. When Thompson & Odell went bankrupt in 1905 and Boston-based instrument maker Vega Company acquired the firm’s assets, Stromberg decided to strike out on his own.

He established Charles A. Stromberg & Son in early 1906 at 61 Hanover Street, producing custom-made banjos, mandolins, ukuleles, harps, glockenspiels, orchestra bells and drums and promoting the shop as the area’s best outlet for “Orchestra, Street and Bass Drums, and Drummers’ Traps.” The company also repaired and restored what Stromberg advertised as “instruments of every description,” though banjos, mandolins, guitars and harps were the most common. While the company’s instruments were far less ornate than others on the market, they were extremely innovative and well-crafted, according to Christine Merrick Ayars’s 1937 book Contributions to the Art of Music in America by the Music Industries of Boston 1640-1936; among their top sellers were the Invincible Orchestra Drum, the Orchestra Drum and the Artist Drum.

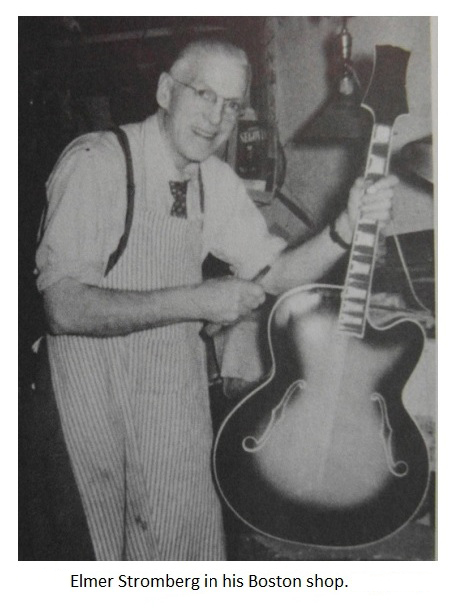

In 1910, Stromberg’s son Elmer, a skilled mechanic like his father, joined the business, remaining there for the next 45 years except for a stint in France during World War I. His oldest son Harry also worked for the company (until 1927), but the official name of the business always ended in “Son,” not “Sons.” Using tools they made themselves, the Strombergs constructed instruments on Hanover Street until around 1915, when they moved to 40 Sudbury Street. In the early ’20s, the company relocated to 19 Washington Street and in 1927 it moved to back to Hanover Street, this time to number 41, where it stayed for the next 28 years.

FIRST GUITARS, MASTER 300/400, NOTABLE PLAYERS

Throughout the ’20s, banjo players in Boston, greater New England and along much of the Eastern Seaboard knew the Stromberg shop as one of the go-to places for a custom-made instrument. When the guitar started to replace the banjo in popular music later in the decade, however, the Strombergs realized that entering the guitar space was the most commercially sensible response, and in 1927 they produced their first models, the carved-top G-1 and G-2. Built mostly by Elmer, they were 16 inches wide (the industry standard at the time), custom-made according to buyers’ demand for special features and received immediate acclaim for their craftsmanship; many compared them to guitars made by Manhattan-based luthier John D’Angelico, widely considered to be the greatest guitar maker of all time.

Guitars were a sideline to the Stromberg’s banjo, mandolin and drum business for most of the next decade but the shop became a popular hang-out for local guitarists, some of whom broke in new instruments before delivery. In 1930, Stromberg reorganized the company in order to put more focus on guitars, which were common in the swing bands of the era but far too quiet to be heard above the blare of their sax-trumpet-trombone horn sections. He put Elmer in charge of expanding the guitar business, but sales remained relatively low compared to Stromberg’s other products for the next several years; at the end of 1933 the company had produced roughly 1,000 banjos, 400 drums and 200 mandolins, but only 100 guitars, according to Ayars’s 1937 book.

Things began changing in the industry and for Stromberg in 1934 when, in an effort to produce more volume for big-band players, Gibson widened the body of its L-5 archtop from 16 to 17 inches and Epiphone responded in 1935 by widening the body of its DeLuxe from 16 to 17 ⅜ inches. The improvement was so dramatic that other guitar companies followed suit, including Stromberg, which widened its G-1 and G-2 models to 17 inches, replaced their laminated backs with maple ones, added hand-carved spruce tops and restructured their f-holes to produce an even louder sound. The “size matters” battle continued with Gibson introducing its 18-inch-wide Super 400, Epiphone introducing its 18 ½-inch-wide Emperor and Stromberg upping the ante in 1937 with its most famous models: the 19-inch-wide Master 400 and the less-ornamented but equally huge Master 300, which were “so overwhelmingly loud” that they were “kind of like a grand piano,” according to David Davidson, the owner of Long Island-based retailer Davidson’s Well Strung Guitars. Stromberg introduced a single-bar bracing design on both Masters to distinguish them from the double “tone bar” (X-pattern) that other archtop makers used.

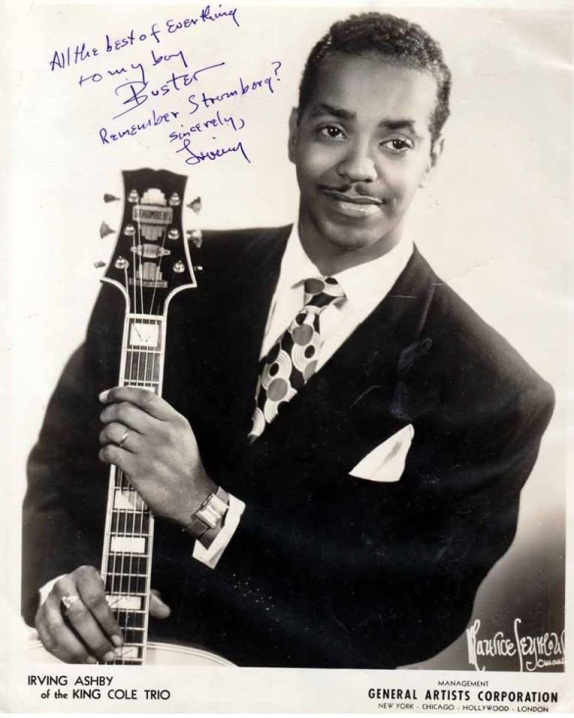

A number of jazz greats used Masters including Freddy Green of Count Basie’s band and Irving Ashby of Lionel Hampton’s and Nat King Cole’s; Ashby’s Master 400 is currently in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, gifted by his wife, Pauline Randolph Ashby. From the late ‘30s through the mid-‘50s, the Hanover Street shop was a must-see destination for jazz cats playing in or around Boston, including Stromberg players such as Laurindo Almeida (Stan Kenton), Mary Osborne (Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonius Monk), Tony Rizzi (Harry James, Les Brown), Chester “Chet Kruly” Krolewicz (Fletcher Henderson), Fred Guy (Duke Ellington) and Barry Galbraith (Claude Thornhill, Art Tatum).

G-5, NOTABLE PLAYERS, STROMBERG DEATHS, NEW “STROMBERGS”

By 1952, Stromberg’s reputation as one of premier boutique guitar shops in the US was firmly established but the Big Band Era had ended and electric guitars had become common, resulting in decreased demand for Masters. To jumpstart sales, Elmer designed the G-5, a new type of 17-inch cutaway that was similar to Epiphone’s cutaway DeLuxe but with less binding, a shorter (23 ½-inch) scale and a price that was nearly 25% lower ($315 [about $3,700 in 2025] compared to the DeLuxe’s $404 [about $4,800 in 2025]). The archtop soon became one of Stromberg’s best-known models (though total production is estimated to be no more than a dozen) and is one of the most historically significant guitars ever made, according to Gruhn’s Guide to Vintage Guitars. Among those who performed and/or recorded with a G-5 were Tony Rizzi, Barry Galbraith, legendary Nashville session player Hank Garland, Grand Ole Opry member Douglas B. Green and John Payne of the supergroup Asia.

Charles Stromberg died in 1955 at age 89, followed later that year by 60-year-old Elmer, who left one G-5 cutaway unfinished. The company closed shortly afterward and, unsurprisingly given the extremely limited output, the value of Stomberg guitars has skyrocketed in over the past 70 years; the average price today is between $16,000 and $20,000, according to Guitar Muse magazine. In 2013, the asking price for a Master 400 that Freddie Green owned (with “FLG” carved into the mother-of-pearl marker at the 15th fret) was $90,000 at Gruhn Guitars in Nashville.

In the early 2000s, Larry Davis of WD Music Products, a stringed-instruments parts supplier in North Fort Myers, Florida, bought the rights to the Stromberg name; since then, he’s sold a line of Korean-made “Stromberg” guitars in the $1,200 range. “[Davis] tricks out these new Strombergs with hardware he knows to be good [and] gets the offshore factory to build them with spruce tops,” wrote Jazz Times’ Russell Carlson in July 2003. “When they come to America from Korea, the new guitars are, according to Davis, more or less taken apart and put together again. He outfits each with La Bella flat-wound strings and has each one set up properly.” Davis offers three jazz-themed models that don’t copy any of the original Stromberg ones (the Newport, the Montreux and the Monterey), though there are some obvious tips of the hat in the headstock shape and inlay. “I’m confident in recommending it to anyone who plays guitar, professional or rank amateur,” wrote Carlson after testing out the Newport. “Larry Davis has begun a new chapter in Stromberg guitar history that preserves the storied name well.”

(by D.S. Monahan)