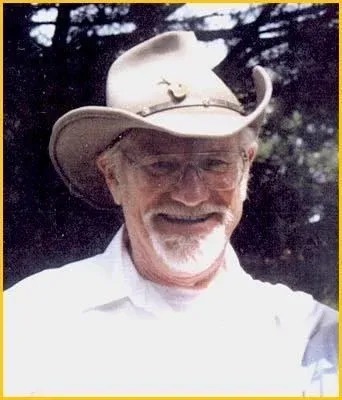

Bill Flagg

Attention, rock ‘n’ roll trivia buffs! One of these four people is widely credited with having coined the term “rockabilly”: (a) Chet Atkins (b) Sam Phillips (c) Conway Twitty (d) Johnny Cash (e) Carl Perkins. Which one?

Trick question! The correct answer is Bill Flagg, who was born in Maine and raised in Connecticut, where he lived his entire adult life. And though most music lovers, even rockabilly fans, have never heard his name, his role in popularizing the genre and in all likelihood naming it in the mid-1950s makes him “the man who laid the golden egg that Elvis hatched,” wrote Lucky Clark in The Portland Press Herald in 2000, the year Flagg was included in the Rockabilly Hall of Fame.

Early Years, Musical Beginnings

Born on March 11, 1934 in his parents’ home on Oakland Road (now Kennedy Memorial Drive) in Waterville, Flagg had deep roots in the city and the surrounding region, his grandfather having been the coachman of the area’s first school bus in the late 19th century – a horse-drawn wagon. Around 1941, the Flaggs moved to Connecticut, but he returned to Waterville every summer, staying with his aunt and uncle.

Flagg started playing guitar in his early teens and by his senior year in high school – 1951, when Chess Records issued what’s widely recognized as the first rock ‘n’ roll song, “Rocket 88,” by Jackie Brenston and His Delta Cats – he was fronting an R&B-covers band that included his classmate John Sligar, who’s credited as the co-originator of the term “rockabilly” since he was in a recording studio with Flagg when he reportedly first used it to describe his songs.

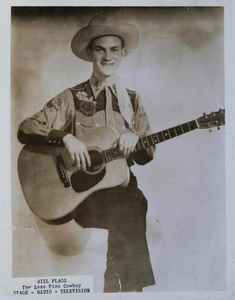

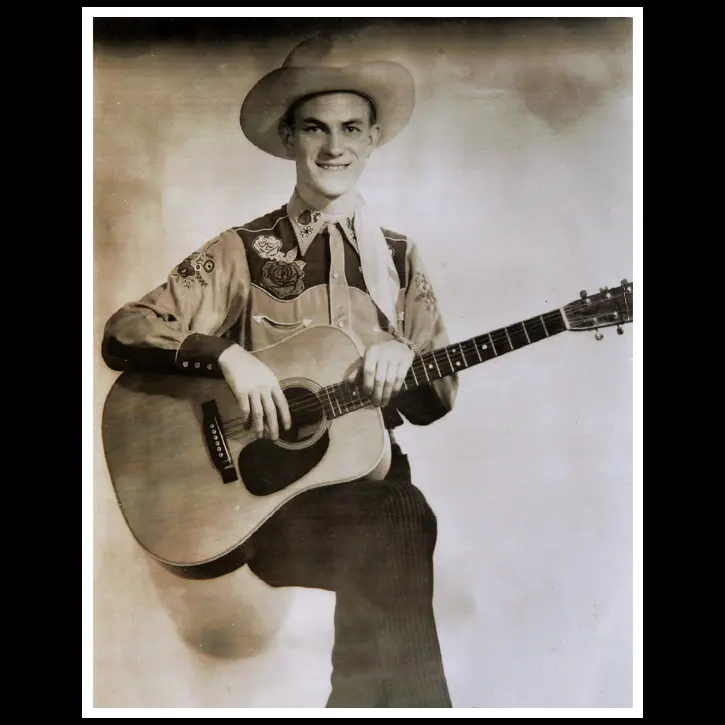

“The Lone Pine Cowboy,” Shift to Bluegrass, Country

Upon graduating from high school in 1952, Flagg started his music career with an instant – and sizable – audience, not under the bright lights of the stage but in the studio of New Britain-based radio station WHAY-AM (910 kHz), where he was a singing cowboy with a regular slot. Billed as “The Lone Pine Cowboy” – Gene “The Singing Cowboy” Autry being his hero – he worked alongside one of the region’s best-known deejays, “Smilin’ Jim” Flaherty, who also managed the Belmont Record Shop in Vernon, at that time the largest supplier of country and western records in the Northeast.

By the end of 1952, Flagg and Sligar had moved away from playing strictly R&B and toward a more bluegrass/country-twinged sound, each on guitar and vocals, eventually developing a style that mixed their loves of R&B, bluegrass and country equally, the same way others had begun to do across the US, the most oft-named examples being Alabama-born guitarist Hardrock Gunter and Virginia-born pianist Roy Hall.

“The fascinating thing about rockabilly was that it was this little localized style that everyone associates with Memphis,” wrote Michael Dregni in Rockabilly: The Twang Heard ‘Round the World (Voyageur Press, 2011). “[But] there were a lot of people in bluegrass and country [outside of Memphis] who were kind of hot-rodding their music.” Yet as popular as R&B-bluegrass-country genre-bending was steadily becoming in the early ‘50s, no artist, band, promotor or record label had given the resulting sound a name. And that would soon change – thanks to Bill Flagg, most rockabilly historians agree.

First Tetra Recordings

Throughout 1953, Smilin’ Jim complimented his fellow on-air personality Flagg on his and his band’s unique style, a potent injection of confidence in the 19-year old since he didn’t see himself as anything especially unique, never having written an original song. Flagg said the original inspiration for his band’s sound was guitarist-banjoist Jody Gibson, who he met by chance at a gig.

“One night this fellow, Jody Gibson, came in with a five-string banjo which was very unusual around here in those days,” he told MassLive in 2015. “So I called him up to play and he did this thing on the five string banjo which was extremely unusual. The crowd went crazy for it and I asked him what it was and he said it was the kind of music Bill Monroe played and at that time it was just called ‘hillbilly music.’”

But Smilin’ Jim’s praise was just the start of the recognition, because late that year Tetra Music exec Monty Bruce, who’d heard Flagg’s radio spots, invited him to record in New York. “I thought this was a big joke,” Flagg told the Boston Globe in 2015. Bruce assured Flagg that it wasn’t, so he, Sligar and two others, traveled to Bell Recording Company on Mott Street (later Bell Sound Studios). They recorded two tracks, the traditional “Roll in My Sweet Baby’s Arms,” which Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs and the Foggy Mountain Boys had popularized in 1951, and the country-blues standard “Sitting on Top of the World.”

Bruce, who had a uniquely direct line to the man credited with popularizing the term “rock ‘n’ roll,” deejay Alan Freed – his father-in-law – was excited about the cuts until Flagg told him they weren’t his own songs. Already faced with a lawsuit over another Tetra artist who’d claimed ownership of a Jimmy Rogers song, Bruce sent Flagg away, telling him not to return until he’d written an original – something Flagg had never done.

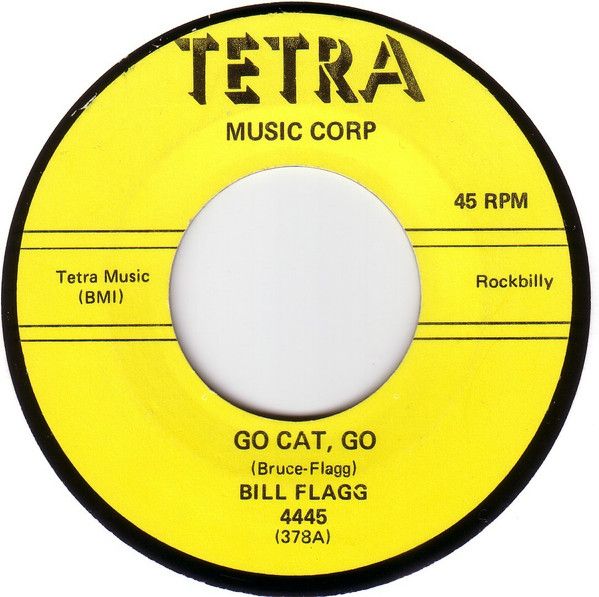

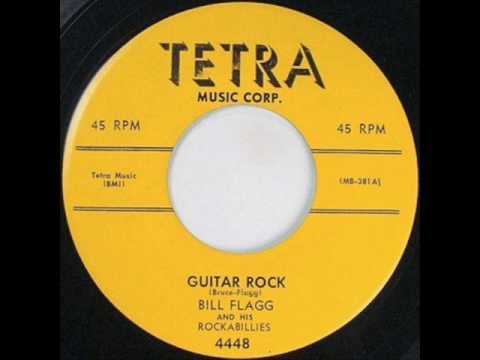

“Go Cat Go,” “Guitar Rock”

In January 1956, Flagg returned to New York, presenting Bruce with his new song “Go Cat Go,” which Flagg thought was nothing special. “Really, I thought it was probably the worst song in the world,” he said in 2003. They recorded the track at Bell Recording Company with a contrabass and two guitars – one played by Jody Gibson since Flagg’s usual guitarist was in jail at the time – and the label loved it, even though Flagg was quite unhappy with how it came out. “To my surprise, and probably to everybody’s surprise, that song reached the Billboard charts,” he said in 2015. “So I had a big record. I didn’t like it, but I had a big record.”

Flagg also recorded another tune he’d recently written, “Guitar Rock,” and Tetra released both tracks as 78s (later as 45s), promoting them as “rockbillie,” the word Flagg reportedly had invented during the sessions, combining “rock ‘n’ roll” and “hillbilly” (a pejorative term for “country” at the time, especially when used by those from north of the Mason-Dixon Line).

First “Rockbillie” Promotion

The singles’ release was a rock-music landmark since it was the first time a label had used the word “rockbillie” in its marketing, establishing a unique legacy for Flagg that’s rivaled by few.

While there isn’t complete consensus on the word’s origin, it’s perfectly plausible that Flagg was the first to use it during his Tetra sessions in ‘56, author Dregni writes in Rockabilly: The Twang Heard ‘Round the World, noting that other artists didn’t use the term before Tetra issued Flagg’s “Go Cat Go” and “Guitar Rock.” Scotty Moore, the guitarist on Elvis’ 1954 rendition of Arthur Crudup’s “That’s All Right,” once made comments supporting Dregni’s: “We all knew we were on to something different [in 1954],” he once said, “but we didn’t have a name for it.”

Alan Freed on “Rockbillie,” “Rockbillie” Becomes “Rockabilly”

According to Flagg, when Freed heard the word “rockbillie,” he told Bruce and other Tetra bigwigs that he didn’t like it; they should modify the term “to give it some class,” he said. Despite Freed’s outsized influence on what records were played on the radio across the US in those days, however, the label ignored his recommendation. Three years later, in the Congressional Payola Investigations of 1959, Freed was found guilty of taking bribes from record labels, obliterating his once-illustrious career.

The first written use of the term – the spelling changed from Tetra’s “rockbillie” to “rockabilly,” as used today – came several months after Tetra had released Flagg’s two singles, in a May 1956 press release describing Gene Vincent’s “Be-Bop-A-Lula,” according to Craig Morrison in Go Cat Go!: Rockabilly Music and its Makers (University of Illinois, 1996).

Several weeks after that, on June 23, 1956, Billboard magazine used the word in a review of Ruckus Taylor’s “Rock Town Rock.” The first record to contain the term rockabilly in a song title was “Rock-A-Billy Gal” by Mearl Allen, released in November 1956 – about 10 months after Flagg’s singles hit the shelves – followed in 1957 by Buddy Knox’s “Rock-A-Billy Walk” and Johnny Cardell’s “Rock-A-Billy Yodeler” and in 1958 by Gene McKown’s “Rock-A-Billy Rhythm.”

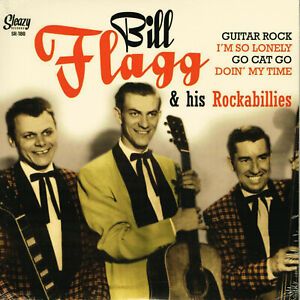

BILL FLAGG AND HIS ROCKABILLIES, 1956/’57 TOUR

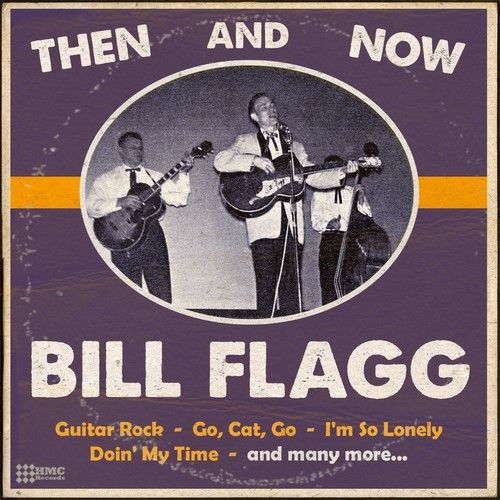

For touring, Flagg formed the trio Bill Flagg and His Rockabillies with Cat Gibson and Ted Barton, barnstorming the eastern seaboard and making appearances on Freed’s show on WINS in New York and American Bandstand in Philadelphia (before the show was nationally syndicated). Despite the relentless road tripping – and the songs’ singular significance in rockabilly history – neither “Go Cat Go” nor “Guitar Rock” ever charted.

By the end of 1957, 23-year-old Flagg was tired of life as a traveling musician and preferred playing local clubs like Shonty’s Restaurant on Main Street in Windsor Locks near his home, where later he became the house act for 12 years (until it burned down in 1967). Compounding his travel fatigue, guitarist Sligar had been imprisoned and his original bass player was, to put it plainly, lost to the bottle. Most of all, he missed New England and the state of his birth. “All of my jobs were from New York down to the South,” he said in 2003. “I never got up to the northeastern part of the U.S., never got up to Maine.”

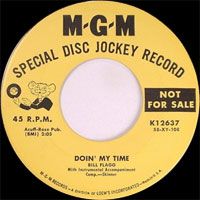

Leaving the Music Business, Hobo Bill and Last Ride

In 1958, Tetra sold Flagg’s contract to MGM Records, which added backing vocals to his next singles, “Doin’ My Time” and “I Will Always Love You,” which Flagg once cited as the final straw in his wanting to deal with record labels, producers or be a touring recording artist at all. By the end of the year, he’d left the music business, settled in Granby, Connecticut and was working with his father, a horse trader who ran a livery ranch.

But, in a testimony to how the music inside a person never really goes away, about 40 years later, in the late 1990s, Flagg formed the bluegrass band Hobo Bill and the Last Ride – largely at his son’s encouragement – and played shows in the local area for the next 25 years. For several years, he oversaw the Hartland Hollow Bluegrass Festival in Connecticut.

“Go Cat Go” Legacy, Rockabilly Hall of Fame Induction

In 1996, Carl Perkins recorded the LP Go Cat Go!, a direct reference to Flagg’s groundbreaking 1956 single, though he did not include the song itself (or “Guitar Rock”) on the album. In 2006, the HairBall8 Records release Go Cat Go: A Tribute to Stray Cats brought Bill Flagg’s genre-naming song to fans’ minds yet again and in 2000 Flagg was included in the Rockabilly Hall of Fame, a Nashville-based organization and website formed in 1997.

FIRST WATERVILLE APPEARANCE, LATER ACTIVITY, DEATH

In 2003, Flagg played his first-ever show in Waterville, Maine, calling his return to the city of his birth 69 years before “a dream come true.” Now 89 years young, “The man who laid the golden egg that Elvis hatched” recorded on his own label, Banner Recordings, and continued to perform semi-regularly in Connecticut until his death in November 2024 at age 90, a remarkable feat considering that he had a major heart attack at age 42 – after which his doctor gave him five years to live – and had two open-heart surgeries and a pacemaker since then.

(by D.S. Monahan)