Elma Lewis

The story of Elma Lewis is like a novel, a real-life story of deep dedication and unwavering vision. Many of those familiar with this extraordinary Roxbury resident and her amazing accomplishments in dance and theatre might not immediately recall her contributions to New England’s music scene, but as a tireless promoter of advocate for the region’s musicians, she takes a back seat to no one. In fact, you’d be hard pressed to find another New Englander who has done more to bring music – all varieties of music – to as many people as the Elma Lewis did.

EARLY YEARS

At the turn of the 20th century, Barbadian immigrants Edwardine and Clairmont Lewis arrived in Boston and the married couple had a daughter on September 15, 1921, Elma Ina Lewis. Experiencing racial prejudice at the level they endured in the city was new to them, but not unexpected.

They had an inner source of pride and resilience, were devotees of Marcus Garvey and his philosophy of self-reliance and nationalism and took young Elma to meetings of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League. In the Lewis family, self-reliance meant caring for your home and for your community and Lewis’ mother had her daughter sweep their building’s steps daily. To her, it was important to do something – anything you could – to improve your home and your neighborhood.

It was this loyalty to Roxbury, inherited from her upbringing, that fueled the adult Miss Lewis to serve her community through her love of the arts. After graduating from Emerson College in 1943 and earning a master’s in education from Boston University in 1948, it seemed like destiny that she would combine the two and teach the arts.

SCHOOL OF FINE ARTS

After borrowing $300 from her father in 1950 (about $3,800 in 2023), Miss Lewis’ vision became very real at 7 Waumbeck Street in Roxbury where she opened the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts. Among the items she purchased for the school, which included a ballet studio, an art studio and a music room, were two secondhand pianos. Almost immediately, she had 25 students. “We were overrun with students,” she told TheHistoryMakers, non-profit research and educational institution committed to preserving and making widely accessible the untold personal stories of both well-known and unsung African Americans.

Asked about her educational approach, Miss Lewis said one important element was teaching young men and young women simultaneously. “For one thing, I didn’t accept money from boys, because I wanted boys,” she explained. “As traditional, Black people educate girls and let the boys rough it. But I couldn’t see how that could be successful, so I wanted the boys to develop. People would always say, ‘You have so many boys.’ And I would just smile. They didn’t know that the boys got something for nothing. Those boys are still in my life today.” By 1955, the school needed a larger space so Miss Lewis relocated it to 449 Blue Hill Avenue. In 1964, she moved it to Charlotte Street and later to the corner of Roxbury’s Elm Hill Avenue and Seaver Street.

NATIONAL CENTER FOR AFRO-AMERICAN ARTISTS, PLAYHOUSE IN THE PARK

In 1968, after the School of Fine Arts had been open for 18 years, Miss Lewis founded the National Center for Afro-American Artists (NCAAA) “to preserve and foster the cultural arts heritage of Black peoples worldwide through arts teaching, and the presentation of professional works in all fine arts disciplines.” She partnered the NCAAA with the School of Fine Arts.

During that time, she decided that an outdoor venue would be the ideal add-on to her vision during summer months, so she established the now-historic Playhouse in the Park. “In the 1960s, Miss Lewis and her students cleared an overgrown area in Franklin Park where the Overlook Shelter had burned and then erected the Playhouse stage to create an open-air performance venue,” according to the Franklin Park Coalition.

Starting in 1968, many in Boston’s Black community heard and saw jazz, African, reggae and Latino music performed for the first time at the venue (this writer included) and a number of the performances were conducted by students from Miss Lewis’ schools. Imagine that: Students from the community performing on stage, outdoors, on summer evenings in the very heart of their community, Franklin Park. The performances, which combined music, dance and sometimes spoken word, ran from July 4th through Labor Day and were free. The evenings were a revelation that brought people together to celebrate their cultural and artistic heritage like no other Boston venue had done before. Over 100,000 attended shows during the first season.

Hey, betcha’ did not know this (ok, neither did I): It was Playhouse in the Park that inspired the City of Boston and community leaders to start Summerthing! Through the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts Black and Brown residents had access to the arts on a level that was lacking in Boston.

NOTABLE PLAYHOUSE APPEARANCES, NOTABLE PATRONS

As a promoter who was determined to present all varieties of music to the community, Lewis brought jazz icons Duke Ellington, Billy Taylor and Max Roach to Playhouse in the Park. Folk icon Odetta appeared there, too, as did the Boston Ballet and the Boston Pops Orchestra. In terms of fund raising, Miss Lewis produced like few in Boston could. Try this on for size: On August 26th, 1969, Wilson Pickett and Sly and the Family Stone were the star attractions at Harvard Stadium to help Lewis raise funds for her National Center for Afro-American Artists. I repeat: Wilson Pickett and Sly and the Family Stone, in 1969!

Miss Lewis became such a powerful personality across Black America that she attracted the attention and support of celebrities including Muhammad Ali, Thomas Dorsey, Nina Simone, Eartha Kitt, Leon Sullivan. The entertainment world came to Boston to help, too; Harry Belafonte, Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, among others, all pitched in to teach, perform or otherwise help raise money for Miss Lewis’ school.

UPTOWN IN THE PARK CONCERTS, DANCE, DRAMA, MUSICALS

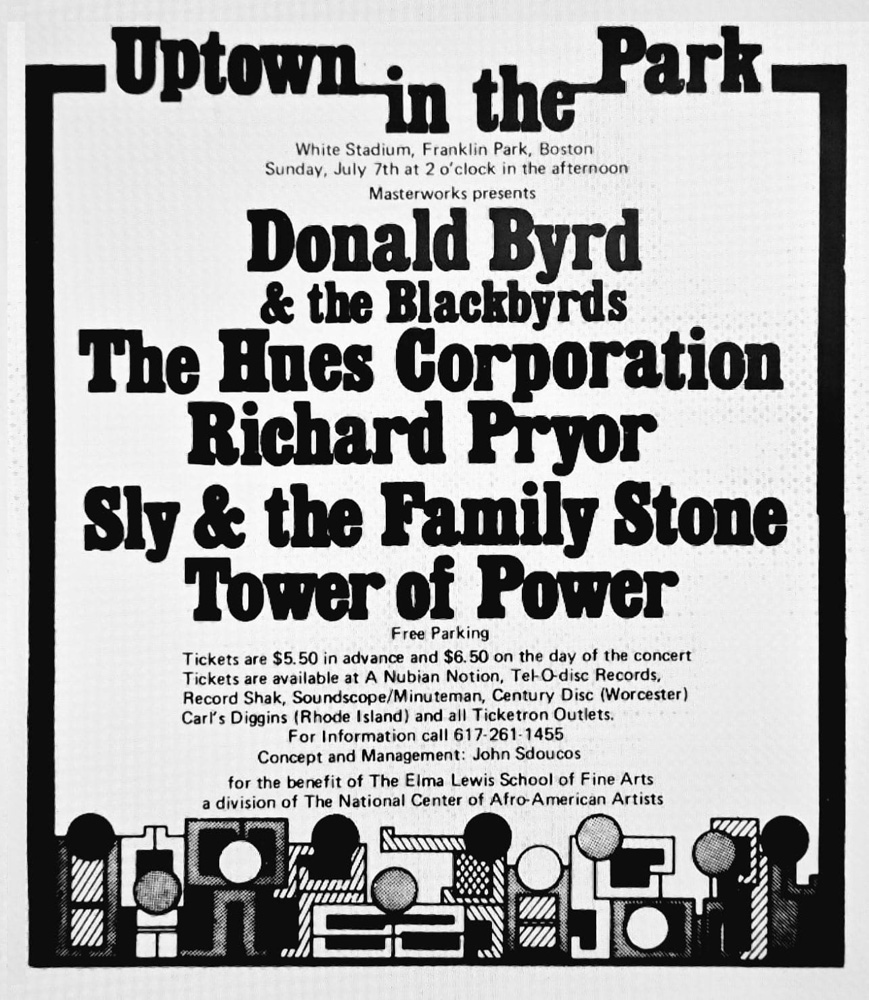

And, of course, in the mid-‘70s there were the two famous Uptown in the Park concerts, produced for the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts, which secure Miss Lewis’ legacy as a powerhouse in terms of concert promotion and production. The first show was on July 6, 1975, at the 10,000-seat White Stadium in Franklin Park, and featured Sly and the Family Stone, Tower Of Power and The Hughes Corporation (remember “Rock The Boat”?). Comedy was provided by none other than Richard Pryor. On the bill the following year were The O’Jays, Parliament/Funkadelic, New Birth and Donald Byrd & The Blackbryds. This writer is pleased to say that I attended that 1976 show – my very first large-scale concert.

As a dance instructor, Lewis had many of her music students from Boston’s Black neighborhoods accompany her dancers. Under her leadership, her troupes performed across the country and overseas, including performances in Senegal, Brazil and parts of Europe. She also presented stage dramas and musicals, and many performers who had their beginnings with her went on to extraordinary careers of their own.

INFLUENCE ON LOCAL MUSICIANS, “BLACK NATIVITY”

Miss Lewis’ vision as a little girl sweeping the steps in Roxbury became a global reality and she gave to her community on a level that had never been achieved before. And in line with her inclusion in the Music Museum of New England for her musical contributions, can anyone imagine how many of Lewis’ students became musicians because they learned piano or other instruments at her school? With teachers there including musician/composer John A. Ross and African percussionist M. Babatunde Olatunji, the students had an array of instructors that any music school would envy. Most students paid minimal fees and many of the teachers at Miss Lewis’ school also came from neighborhoods in Boston.

And how could one speak about Miss Lewis and music and not mention that she started the wintertime performances of Langston Hughes’ famous gospel play “Black Nativity” (written in 1961)? Since 1969, people going to see a performance of “Black Nativity” has been a Boston tradition and it was Miss Lewis and her vision that started it all; for the first several years, she directed the performances herself.

SCHOOL OF FINE ARTS CLOSING, MUSEUM, LATER YEARS

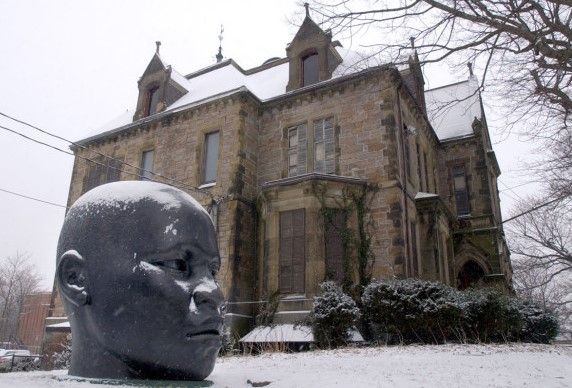

In 1985, the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts closed its Elm Hill Avenue location following a fire. The NCAAA acquired the Abbotsford, a neo-Gothic home at 200 Walnut Avenue in Roxbury built in 1872 by architect Allen Frink (a Roxbury native), according to the Boston Preservation Alliance, and converted it into a museum to showcase work from African, Afro-Latin, Afro-Caribbean, and African American artists.

Even in her declining years, Miss Lewis remained a vocal supporter of the arts and powerful presence in Boston and, as she did throughout her life, she served her community as an advocate for justice and fairness. She was as tough in her position on racial issues and poverty as she was in demanding that her students make every effort to achieve their inner greatness and her students remember her today as a disciplinarian to whom they gave their full attention.

Miss Lewis never had any children of her own and says that she regretted that at one point in her life, but not in later years. “I used to lament the fact that I hadn’t married and had children,” she once told TheHistoryMakers. “[But] I have more children than anybody I know. They don’t let me need anything or want anything that they don’t come and fulfill.”

DEATH, LEGACY

On January 1, 2004, Elma Lewis died at the age of 82 in her Boston home from pulmonary complications stemming from diabetes. As the Grande Dame of the Arts in Roxbury, she left an indelible mark on the Boston and greater New England music scene. Through her promotion of all types of music, her thousands of her students, their children and their grandchildren, her vision remains alive today.

I am proud to write the following piece for the Music Museum of New England to review and celebrate the invaluable impact of her contributions to music. At the same time, I must mention that while the Music Museum of New England recognizes people for their musical contributions, Miss Lewis’ contributions to dance and theater are equally remarkable.

(by Edwin Sumpter)